Chartbook 310 The shock of the new: Dollar dominance and modern monetary macro in the 1920s. (Hegemony note 5)

I’ve been arguing in this series of “hegemony notes” that the question of world order in the 20th century, the question of hegemony, is misunderstood if it is seen as part of a deep historical sequence that stretches back to the Middle Ages. Instead, I am arguing that it was a radically new problem, posed for the first time by the explosion of inter-imperial competition and violence that culminated in World War I. The result after 1918 was the struggle to shape a new type of great power relations.

This took many forms:

The explicit effort to manage imperialist competition in the key arena of East Asia and China in the form of spheres of influence and creditor cartels.

Arms control - Washington Naval Treaty of 1921/2.

New international organizations, above all the League of Nations and its mandate system, especially in the Middle East and Africa.

Most importantly of all, in the field of global finance.

As I’ve argued in previous posts, in global finance, these efforts were centered on the new problem of political debts and reparations within the core group of great powers. This spiraled out from the core problem of inter-allied debts owed to the United States. But as I want to argue in this post, it went beyond the question of debts to the foundations of the monetary order. The new mode of great power relations was formulated, aside from the question of debts, also in the altogether new domain of macroeconomic management. This centered on monetary relations, exchange rates, inflation and central bank relations.

In the 1920s, together with the problems of international finance, and the related question of the balance of payments, questions of currency and inflation constituted a new intellectual field of monetary macroeconomics. For the first time in the immediate aftermath of World War I, a global economic conjuncture was grasped, the world over, within the frame of macroeconomics, organized around two simple conceptual frames - the quantity theory and the purchasing power parity theorem. It was against the backdrop of this newly unified understanding of the world economy that the question of US power was conceptualized, as a question of how best to architect a new kind of managed and necessarily political monetary system.

The association of the problem of American hegemony with the emergence of macroeconomics as a field of knowledge, is not new. Following Charlie Maier’s influential essays on the Marshall plan era, it is common to associate the rise of the classic form of American hegemony in the 1940s with a discourse of productivism and the macroeconomics of growthmanship. Others have made the case for the importance of global Fordism in the interwar period, a topic to which we will return.

I agree that macroeconomics was indeed a crucial intellectual frame of US power in the 20th century. But, the first framing was not that of the 1940s, or that of Fordism. The first macroeconomic framing of America’s global power took shape immediately after 1918 around the question of debts on the one hand and inflation and exchange rates on the other.

Macroeconomics, as opposed to microeconomics, is the study of the economic system as a whole. It is a domain often associated with the figure of John Maynard Keynes and the breakthrough of his General Theory published in 1936. But General Theory-centric histories of modern economic knowledge mistake the key themes, the key locations, the key personnel and the chronology of the emergence of macroeconomics.

The origin of modern macroeconomics is not to be found in the 1930s, in debates around unemployment. As David Laidler argued in his classic study of the Golden Age of the Quantity Theory, modern macroeconomics emerged in the late 19th century from debates around inflation and money. Keynes was already an important voice in those discussions on either side of World War I. But, as he himself would have readily acknowledged, he was just one of a number of thinkers seeking to free economics from the mental and practical shackles of the gold standard.

From the late 19th century until the early 1930s the common preoccupation of the first generation of macroeconomist was to explain fluctuations in the aggregate price level as a function of the monetary order.

Since price is an inherently relational concept, the aggregate price level i.e. the “price of everything” does not have an obvious meaning. A downward or upward movement in particular prices, whether it be food or energy prices, does not a general inflation or deflation make. A general inflation or deflation can be defined logically only in relation to something other than the prices of goods and services that are thought to be fluctuating. That “other”, that external standard of judgement can only be money - the unit of value that stands in relation to all goods and services. And this was, indeed, the origin of macroeconomic thinking: the struggle to explain the fluctuations not of particular prices but of all prices as the expression of an imbalance produced by the gold standard between the stock of money and real economic activity.

The central theoretical idea around which the new macroeconomics was organized was the Quantity Theory of Money, which had a lineage which went back at least to Hume and the 18th century, but was given more precise quantitative and algebraic expression in the late 19th century by British and American economists, notably Alfred Marshall and Irving Fisher. Put simply, it argued that the aggregate price level would vary with the quantity of money in circulation and its velocity of circulation.

It was that theory that allowed contemporary economists to argue that the first impact of the formation of the international gold standard in the late 19th century - an ad hoc process driven by separate national currency choices - was to make money scarce and induce a general deflation that did serious damage to heavily indebted producers, notably farmers. The money supply being constrained by gold had become scarce in relation to volume of economic activity and the demand for credit, so the value of gold-backed money rose and the price of goods declined. The world suffered a deflation. Then, from the 1890s, as South African gold flooded the system, the result was the reverse: an increasingly marked inflation. Both these price movements distributed costs and benefits between creditors and debtors and unleashed movements to politicize money. Most notable were the populist movement against agrarian deflation in 1890s in the US (see Chartbook 44 on the William Jennings Bryan) and the strike wave across the industrialized world fueled by the inflation of the 1900s and 1910s.

If the problem was defined in these terms, then a new role became imaginable for economists. In a radical departure, the American Irving Fisher was the first to champion an actively managed currency that would compensate for underlying imbalances and aim to preserve price stability, thus sparing both the economy and society disturbing changes in the value of money. This was a self-consciously activist doctrine. Confusingly, by a bizarre twist of historical fate, Fisher’s Quantity Theory would become associated in the 1970s with the monetarist attack on Keynesianism. What this obscures is the fact that twentieth-century monetarism and Keynesianism were both born around 1900 from the same preoccupation with macroeconomic stability. The difference was that later versions of Keynesianism would put the focus on full employment as the key variable. But in the early 20th century, Cambridge-school economists, including Keynes, other economists around the British empire, American followers of Fisher and Europeans, including Gustav Cassel in Scandinavia and Joseph Schumpeter in the German-speaking world, all used the quantity theory to formulate the outlines of a new intellectual domain of macroeconomics as a science of economic stabilization.

If fluctuations of the price level under the prewar gold standard gave macroeconomics its first impulse, the impact of World War I was far more violent and fundamental.

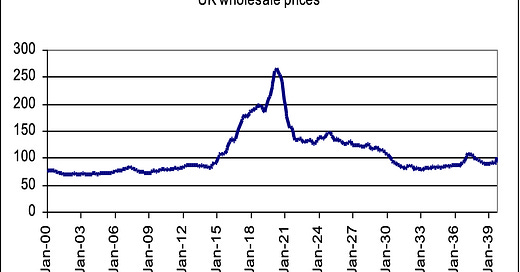

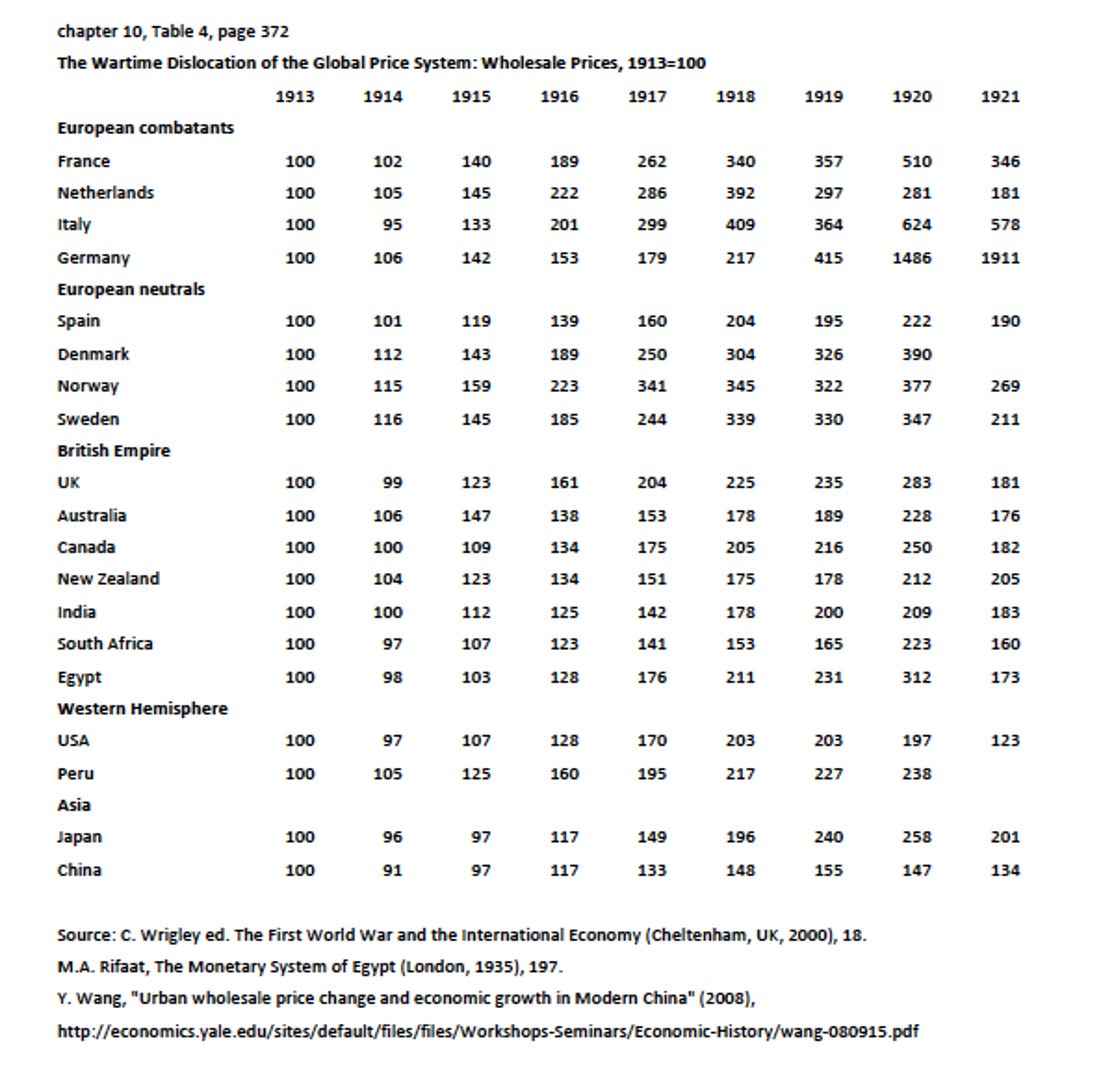

When we think of inflation and World War I we think of Germany. But, in fact, the Great War resulted in a comprehensive dislocation of the price system around the world. Under the pressure of wartime spending and huge deficits, prices surged everywhere. After 1914, literally nowhere on the planet was exempt from inflation.

Not only that, however. As the gold standard was abandoned and capital and goods were no longer allowed to circulate freely, the global monetary system lost the appearance of uniformity and common movement that had once founded the sense of “naturalness” that surrounded it. Not even inflation was any longer a uniform phenomenon.

During the war, national monetary and financial systems were managed according to the dictates of the economic and political situation and the surging demands of the war effort. The expression of this disintegration was that prices rose extremely unevenly across countries, producing huge shifts in the terms of trade, competitiveness and purchasing power.

This robbed the monetary and financial order of legitimation as a “natural” order and made it an object of political contention. Even at the new center of global power, in the United States, as I outline in hegemony note #4, the stresses of wartime mobilization tore at the social and political order. The Wilsonian project of the “new freedom” collapsed between 1918 and 1920, triggering a savage deflation. The “normalization” of fiscal and monetary policy amounted to a reactionary backlash against social and political change.

The impact of the American deflation on the rest of the world was spectacular and drove home the fundamental shift that had been brought about by the war.

From 1914 onwards the might of the British Empire and its allies had been at the mercy of US loan policy. Now they found that their efforts to manage the aftermath of the Great War were dictated by the US too. Budget balance depended on the terms of war debt deals that might be agreed with American negotiators under the watchful eyes of the Congressional War Debt Commission. But even more urgent was the impact of US macroeconomic policy.

The global impact of America’s deflationary policy in 1920-1921 was novel and dramatic. America’s fiscal policy and tariffs sucked demand out of the global economy at the same time as the first rate hikes ever delivered by the Federal Reserve sucked gold and with it monetary liquidity out of the world economy. And rather than responding to the huge gold inflow by loosening policy, as the rules of the gold standard should have dictated, the Federal Reserve, instead, continued to hold a tight policy. This compounded the deflationary effects on the world economy.

Hypothetically, the rest of the world could have bucked the Fed’s deflationary policy. But it would have done so at the risk of currency devaluation and spiraling inflation. This would have hurt the standard of living and raised the domestic cost of US dollar debts. If you wanted to gain a favorable debt deal, or receive new lending from Wall Street, you needed to stick close to US policy. The effect was to transmit deflation to the rest of the world.

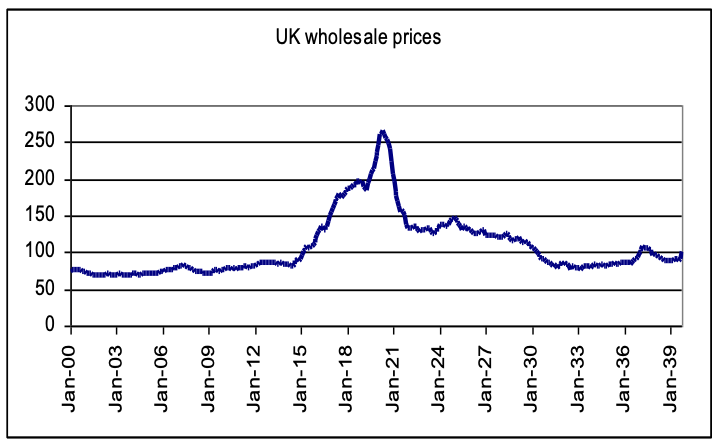

As the table above shows, prices plunged between 1920 and 1921. The UK, the hub of the Imperial economy, and the second most important economy after the United States, plunged into a shock deflation in 1920-1921. Interests rates were hiked. Wartime spending was slashed. Promises of “homes fit for heroes” were abandoned. Prices collapsed chasing America’s deflation in a downward spiral.

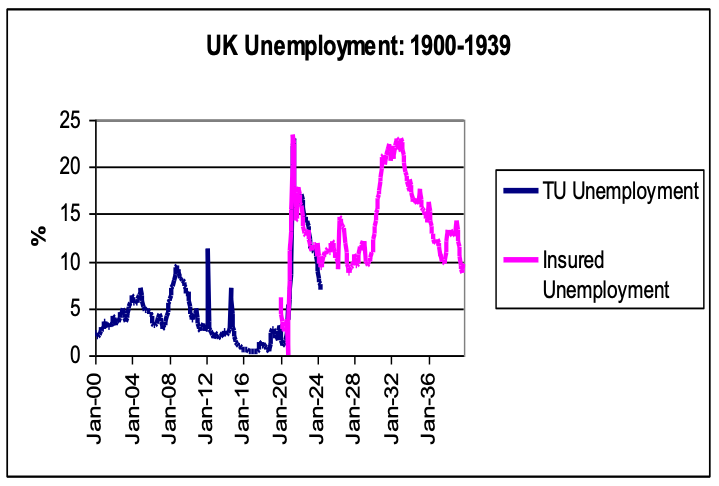

As in the US, the effect on the real economy in Britain was dramatic. In the UK the misery of the interwar period began not in 1929 with the Wall Street crash, but in 1920 with the great postwar shock. Unemployed surged in 1920 and never recovered.

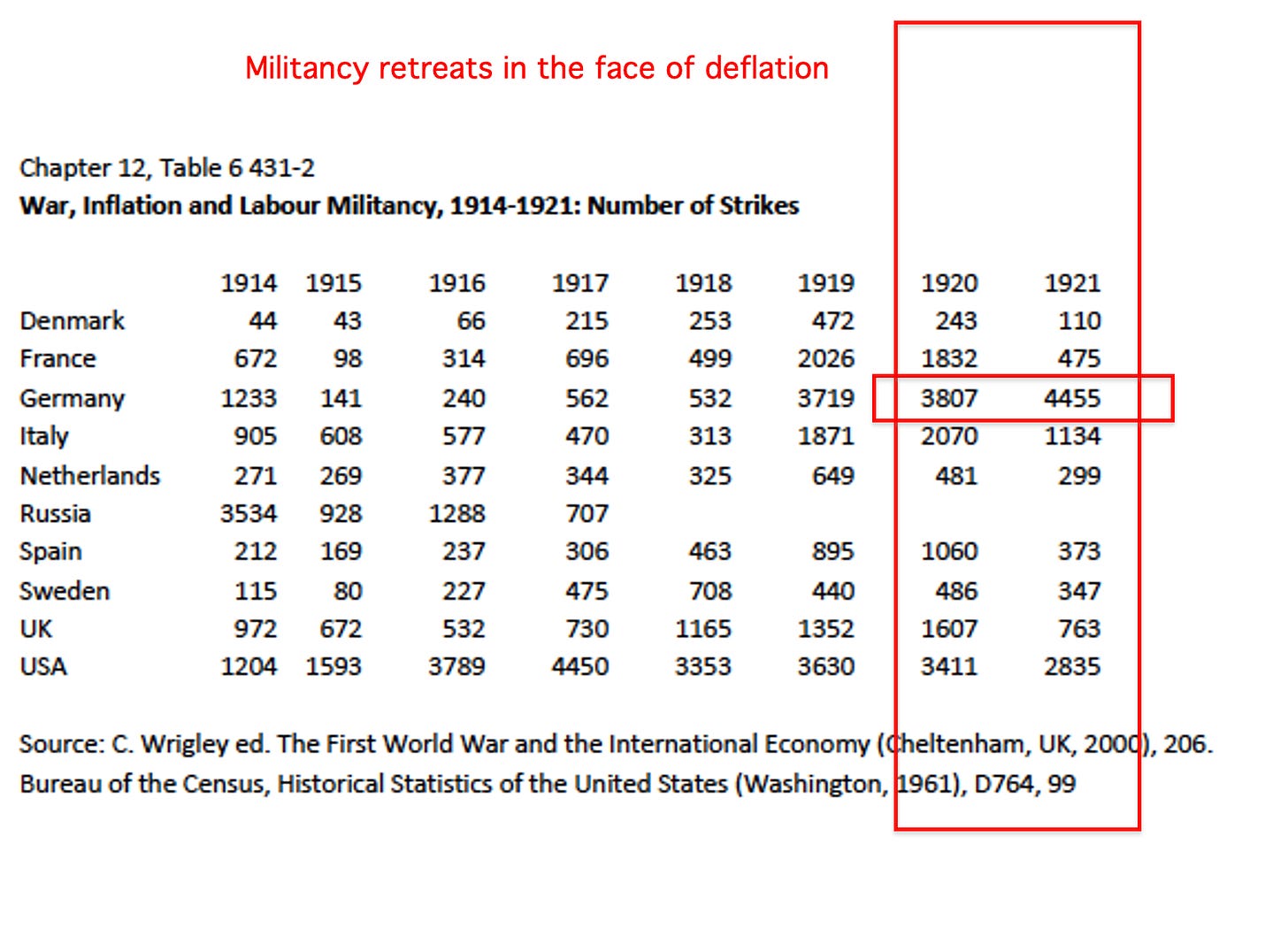

The effect, as in the United States was to reverse the balance of power between organized labour, capital and the government and its creditors. Across the world, the postwar strike wave was broken in what Charles Maier evocatively referred to as the “global thermidor”.

As prices collapsed and unemployment surged, labour militancy declined. In Italy, under the sign of fascism it was crushed with main force. However, as important as squadristri violence undoubtedly was, the focus on para-military violence in the aftermath of World War I in much recent historiography is simplistic and literal minded. In general what did the work of conservative restoration even in Mussolini’s regime was not street-fighting, but the dull compulsion of deflation.

Tellingly, the global deflation extended even to Weimar Germany, the poster child of hyperinflation. Between February 1920 and May 1921 - the harshest period of deflation in the US and UK - prices in Germany fell by 25 percent. As elsewhere, this led to a painful rise of unemployment. Unlike Britain and the US, the Weimar Republic was too fragile to stay the course and slid back towards inflation ad ultimately hyperinflation.

It was against this background of a boom to bust business-cycle, intense socio-economic struggle and looming war debts, that financial diplomats and experts considered how to rebuild the world monetary and financial order. In diplomatic terms this involved a series of conferences, amongst others at Brussels, Cannes and Genoa culminating in the Dawes debt deal of 1924 and the restoration of the gold standard in most advanced economies in the second half of the 1920s. But rather than getting dug into the details of financial diplomacy I want to focus here on the discursive shift that accompanied the process of postwar monetary reconstruction and, specifically, the way in which after 1918 the problem of America’s centrality was umbilically linked to a new macroeconomic understanding of money, prices and exchange rates.

To be clear, the question of US hegemony was formulated in this context not as a triumphant answer, but as a troubling question. But, it was all the more clearly formulated for that. It was Keynes, amongst others, who crisply described the situation in lesser known works that followed the Economic Consequences of the Peace, such as his Tract on Monetary Reform of 1923.

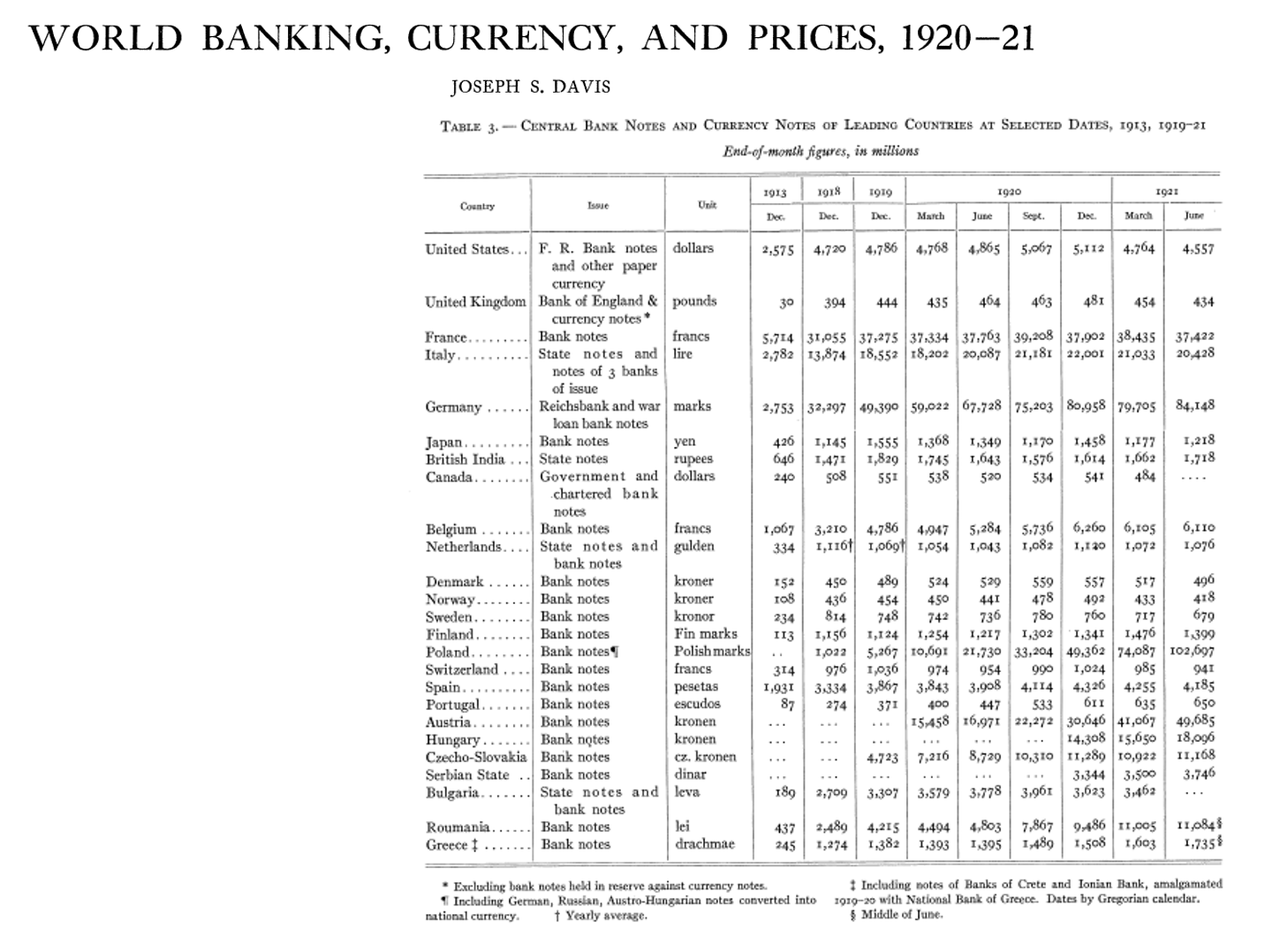

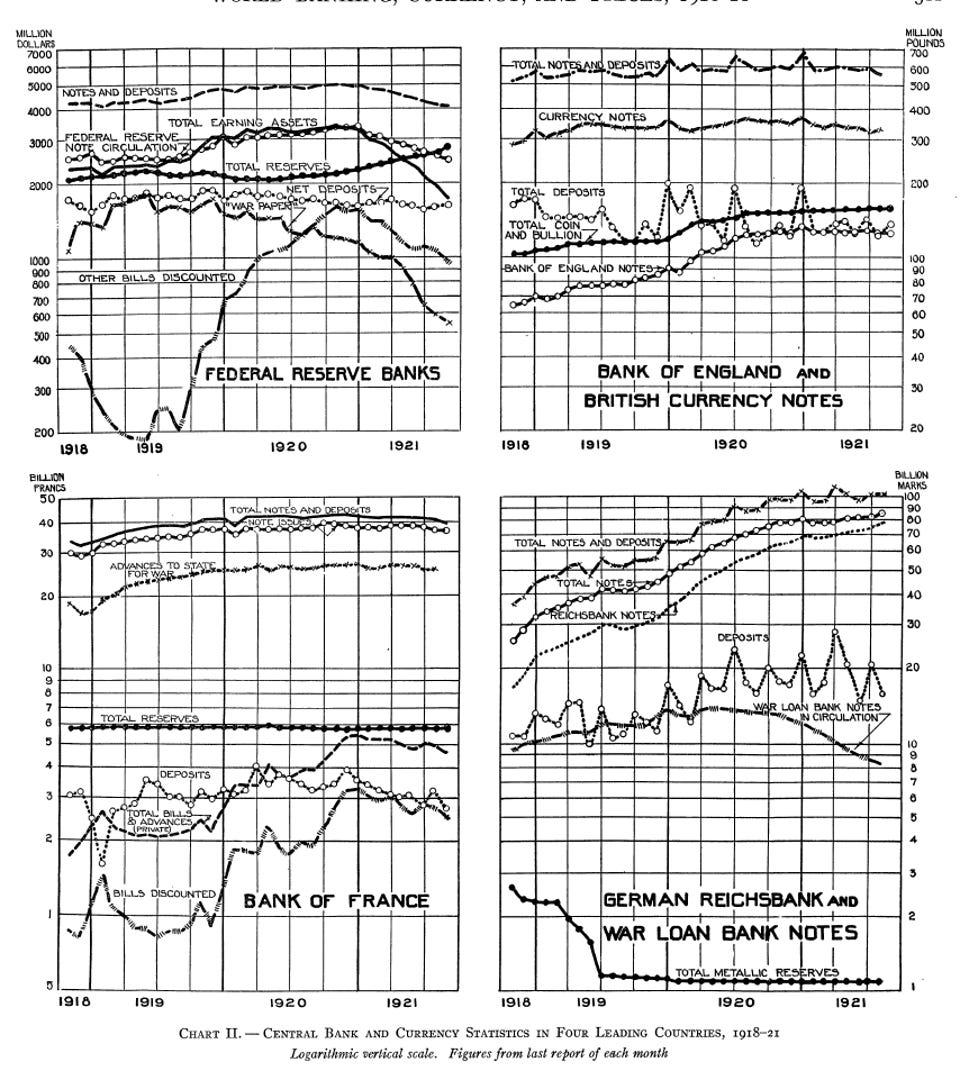

Developing the first statistical experiments that had been made before World War I, economists around the world tracked the rollercoaster of the postwar monetary system with real time data. For the first time, the entire world economy was mapped as an interconnected monetary and price system, in real time. Economists compiled tables of what would later be called “narrow money”.

They also tracked “broad money” (bank credit).

By way of the Quantity Theory, the fluctuations in credit were then related to the price level. And the movement in relative prices in two countries could then be related in real time to exchange rates. And the crucial point was that in the aftermath of World War I none of this could be regarded as “natural” system. The entire system was politicized. Every movement in money, credit, prices and exchange rates posed the question: Should the aim be stabilization or restoration to pre-war conditions. If stabilization or restoration was the goal, what was is it that should be stabilized or restored? Was it prices that mattered, or exchange rates, or parity with gold, or the value of debts?

A text like Keynes’s Tract on Monetary Reform published in 1923 is illustrative of the debates of the period. Keynes compiled data for the movement of bank deposits, cash in circulation and the price level. From these, Keynes then estimated his personal version of the quantity equation, relating the quantity of money and its speed of circulation to the average price of goods. He then concluded: “the moral of this discussion … is that the price level is not mysterious, but is governed by a few, definite and analysable influences. Two of these … are under the direct influence of the central banking authorities.” The third term in his equation, the speed of circulation, depended on the animal spirits of the economy. But this did not mean that the price level should simply be allowed to fluctuate, but rather than the central bank should use those variables that it did control to offset shifts in private credit activity. Policy-makers had a choice. They could seek to promote inflation, deflation or attempt to hold the price level constant. Each of these was a choice with different distributional consequences within the domestic political economy. Inflation would tend to benefit producers over creditors, deflation would have the reverse impact. Price stabilization was a choice to underwrite the postwar status quo, whatever that happened to be. Keynes preferred this latter option. That could be debated. But what could not be debated was that each of these choices would also affect the external standing of the currency. Relatively rapid inflation would tend to depreciate the currency, stabilization or deflation would have the reverse effect.

All of these trains of thought are obvious today. In the aftermath of World War I they were articulated for the first time as a fully fledged roster of options with a real time economic analysis to back them up. And this happened all over the world at the same moment. Keynes himself mapped the world. But so too did analysts in the new centers of economic research in Harvard and Washington, in Stockholm, in Berlin, in Cairo, in the Raj, in the Soviet Union and in Tokyo. All of them faced the same realization of the choices inherent in monetary and financial policy and their implications for domestic society, distribution and global standing.

If the 19th century gold standard had been the era of monetary absolutism, then for Keynes and his cohort, the effect of World War I, was to usher in a new era of deliberate, self-made constitutional government in monetary affairs. Monetary policy had become, whether one liked it or not, a domain of chosen, more or less deliberate management. Even if some countries, such as the United States maintained a gold anchor, the market for gold and silver was so regulated that it too was a political price. So it wasn’t gold that regulated the system so much as political decisions that regulated the value and even the supply of gold.

This in turn meant that the framework of international monetary affairs also lost its natural hierarchy and shape. The war had left the world in chaos. The question after 1918 was to reshape it deliberately. The role of monetary experts like Keynes and his counterparts in Europe and the US was to guide this process.

If one could no longer point to either an inherited or a natural order this dramatically raised the stakes. As far as international affairs were concerned, this meant that the real choice was between degrees of hierarchy. And this is where the question of hegemony was formulated explicitly for the first time. If the monetary system was to be reconstructed after World War I as a deliberately managed system and that system was to have only one center, there was only one possible choice: the United States.

The US clearly exercised power over the entire global economy. Given the structure of war debts it did so with a power that Britain had never exercised in the classic era of the gold standard. The flux of money in and out of the City of London before 1914 no doubt had a political logic. But that was very different from that at work within the network of war debts and reparations since 1917, in which negotiations took place between government and thus effectively between tax-payers. The shock of US deflation between 1920-1921 made clear that America’s influence was not limited to matters of medium- or long-term fiscal policy. It drove interest rates, exchange rates and the price level.

As the shock of 1920-1921 made clear, the decision to rebuild the global monetary system around the de fact power of the dollar would create a radically new center of power; aloof from Europe; driven by its own social and economic crises; governed by the fickle forces of American democracy and with less than ten years experience of financial leadership.

Nothing like this had ever existed before. Never had the monetary system been so politicized. Never had such a powerful cluster of states been so subordinated to a single dominant financier and one outside Europe, to boot.

This was the radical new reality created by the drama of the war, this was the problem of hegemony understood in its historic novelty and Keynes for one was convinced that it was the proper mission of the British elite to resist this development with all possible intelligence and energy. Under prevailing circumstances to allow the formation of a system of managed money with the United States as its sole, controlling center was a highly dangerous experiment.

In due course, Keynes did not disagree that a single, centralized monetary system regulated from the United States would be the optimal solution. But that double innovation - recognizing the monetary order as managed and shifting the center of that management to the United States - was too risky to undertake immediately.

Keynes actually credited US monetary policy with being far more influenced by new-fangled economic thinking and more modern than its European counterparts. But he nevertheless insisted: “It would be rash in present circumstances to surrender our freedom of action to the Federal Reserve Board of the United States. We do not yet possess sufficient experience of its capacity to act in times of stress with courage and independence. The Federal Reserve Board is striving to free itself from the pressure of sectional interests; but we are not yet certain that it wholly succeed. It is still liable to be overwhelmed by the impetuosity of a cheap money campaign. A suspicion of British influence would, so far from strengthening the Board, greatly weaken its resistance to popular clamour. Nor is it certain, quite apart form weakness and mistakes, that the simultaneous application of the same policy will always be in the interest of both countries. The development of the credit cycle and the state of business may sometimes by widely different on the two sides of the Atlantic.”

As Keynes put it: “We have reached a stage in the evolution of money when a “managed” currency is inevitable, but we have not yet reached the point when the management can be entrusted to a single authority.” He agreed with contemporaries like Ralph Hawtrey that in the best case there would be close cooperation between the Fed and the Bank of England. But the best policy was for the Fed and the Bank of England to separately pursue domestic price stabilization. What would then result was a natural stabilization of the exchange rate, at the parity dictated by their respective price levels, rather than some arbitrarily chosen level, such as the prewar parity of the pound versus the dollar. That would no doubt suit bond holders but it would at the expense of production and employment and social balance in Britain.

Keynes thus imagined, as many British policy-makers did at the time, the resolution of the World War I crisis being a kind of parity between the United States and the British Empire. This was the logic enshrined at the same time in the naval agreement that fixed the ratios of the British and American battleship fleets at 5:5 with Japan and the other naval powers allocated smaller rations accordingly.

As for currencies, for the rest of the world’s economies, Keynes suggested that they align themselves between the dollar and the sterling zones. If he resisted a unipolar system he did not envision a multipolar system either.

What actually emerged after 1923 was a messy compromise of unitary and dualistic monetary orders in which the gold backed dollar was far more dominant than Keynes approved of. I will discuss that interwar monetary order in subsequent posts. The point to be made here is simply the clarity with which the novel problem of hegemony was framed in the field of monetary macroeconomics in the aftermath of World War I.

This was the result of the fact that the sudden rise of the United States as the de facto center of a fundamentally rewired system coincided with a basic conceptual shift that allowed the monetary system to be seen as a political construct. The denaturing of the gold standard and the emergence of the new field of monetary macroeconomics combined to pose the question of global financial leadership in a way it had never been posed before, compounding the shock of discovering that the United States was the obvious answer to that question of leadership. Basic questions of monetary governance would never again have the feeling of stark novelty they had at that moment.

Masterful, and as is usually the case with Tooze, careful not to make uncautious claims about the motivations of the the players involved at the time. Readers who are interested in a more sinister interpretation of American motives during the period are encouraged to investigate Michael Hudson's "Super Imperialism. The Economic Strategy of American Empire. Third Edition" or the first few chapters of his "The Destiny of Civilization: Finance Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism or Socialism" both of which outline how the refusal of the US to forgive the war debts of its WWI allies represented a departure from previous European practice with serious consequences for the next 30 years in world history and ultimately resulting in the world-girdling dollar system and its various associated agencies (Bretton Woods, World Bank, IMF).

Somewhat related is John Perkins' "Confessions of an Economic Hit Man" exposing the mechanisms and consequences of US dollar diplomacy among Third World countries in the post-WWII era.

Interesting. And important.

In the first world war, the Netherlands was neutral, contrary to the first table.

If I remember correctly (and I may not), Britain was the largest creditor nation in 1914. The US entered to war quite late and so didn't have to pay for much of it. That's how Britain turned into a debtor nation. The process was repeated in 1939. It got so bad that Britain secretly paid for its last imports, before the US joined WWII, with Belgian gold held for safekeeping in the Bank of England.

I'm not an American, so I don't really know the domestic history, but various political enthusiasms, like the pro-silver movements, made the US seem like an unsafe manager of the world monetary system.