Imagining a really bad future for American leadership in the world economy? Want to know what hegemonic malfunction really looks like? Check out the politics of Washington DC, in the immediate aftermath of World War I! The combination of domestic and international policies adopted at that point was uniquely counterproductive and reflected a crisis on the US home front that is underrated in its severity.

In 1918-1919 Woodrow Wilson had become a global political sensation as the man who would orchestrate a postwar order.

But, what became clear at that same moment is that unlike the conductor of a symphony, the American President was not raised above the orchestra. He was fully immersed in the cacophony of the moment.

In the November 1918 Congressional midterm elections, amidst what we would today no doubt call “polarization”, Wilson lost his majority in Congress.

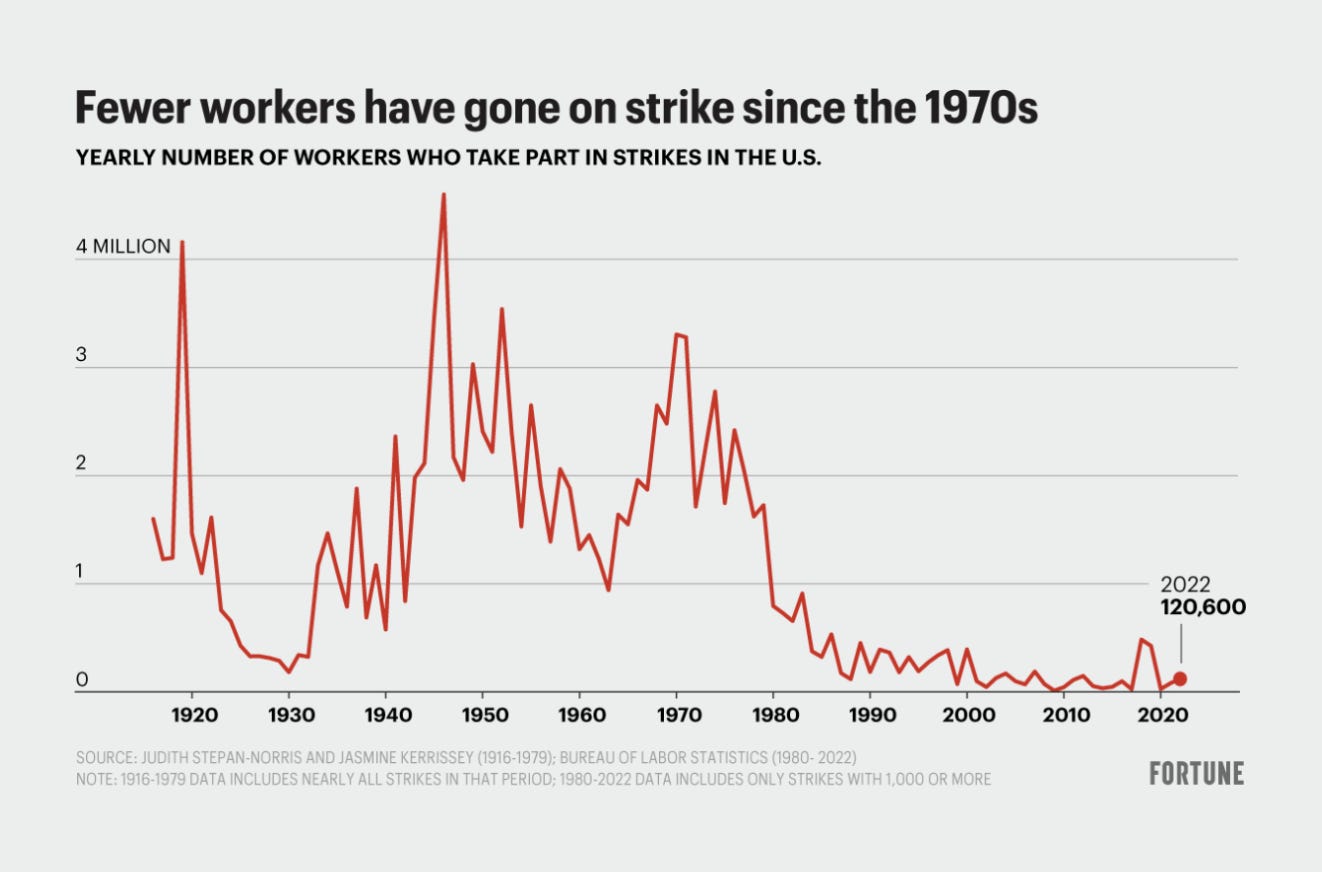

American society was in turmoil. Prices were surging. In 1919-1920, over 4 million workers were involved in strikes. In the “red summer” of 1919 Washington DC, Chicago and other cities were convulsed by lethal race riots.

On November 19 1919, after months of fruitless negotiations, following a breakdown of relations between the Wilson White House and the Senate Republicans, the US Senate refused to ratify Versailles Peace Treaty, including the League of Nations Covenant, the future design of a world order shaped more than anyone by US President Woodrow Wilson. The entire postwar order notionally negotiated at Versailles that had been built in crucial respects around American participation had lost a key anchoring.

Meanwhile, the US was in the midst of a postwar inflation and a panicky red scare. To calm the increasing sense of disorder, the Federal Reserve, which at this point was just seven years old, embarked on its first attempt to impose a serious rate hike. Between December 1919 and June 1920 the discount rate charged by the Fed to banks increased from 4.75% to 7% in June 1920.

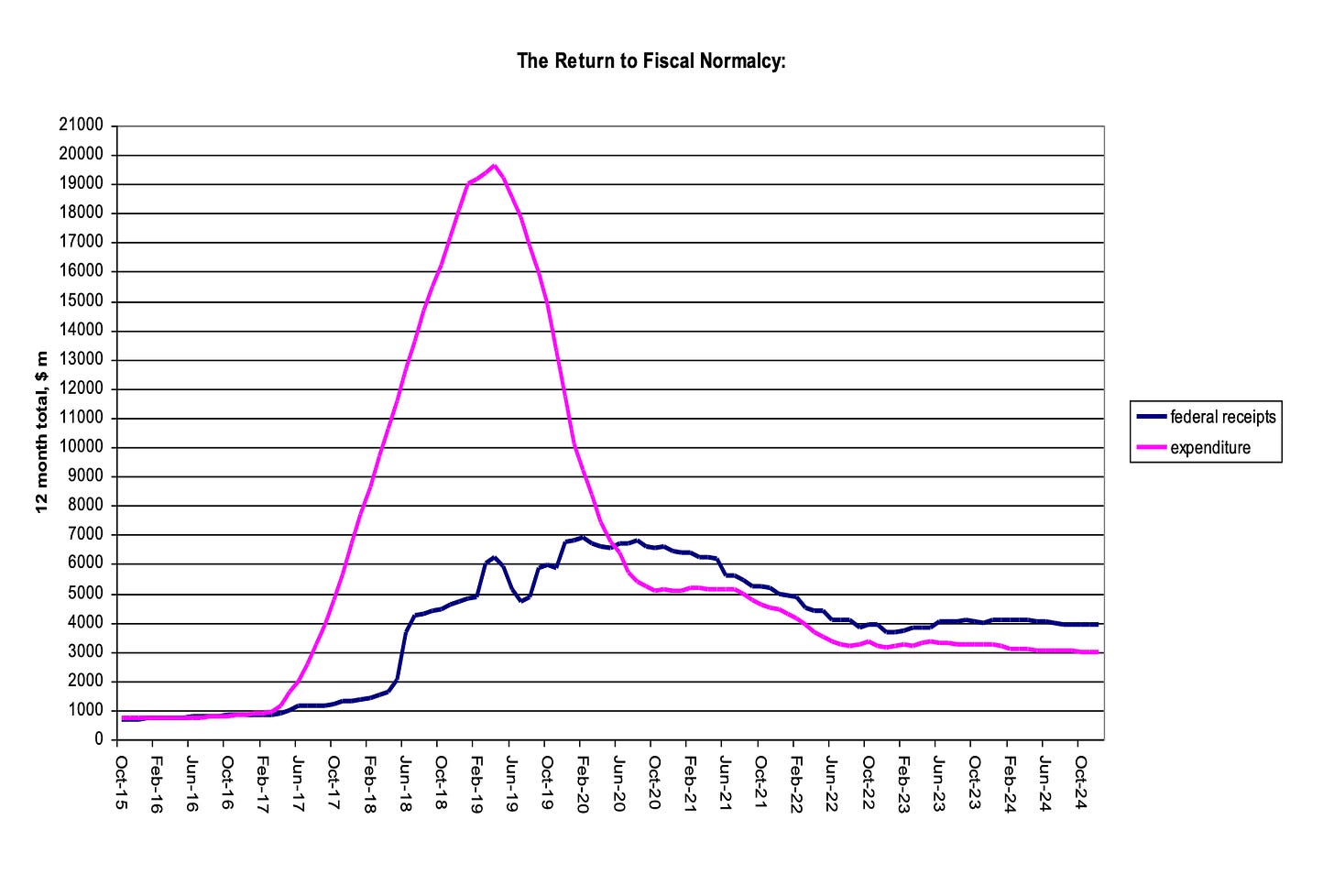

At the same moment, over the winter of 1919-1920, US fiscal policy underwent a wrenching shift. Whilst through the summer of 1919, under the impetus of the war, expenditure had still been increasing. From the summer of 1919 it was sharply curtailed. By the summer of 1920, federal receipts exceeded expenditures. The Federal government had delivered a dramatic fiscal shock.

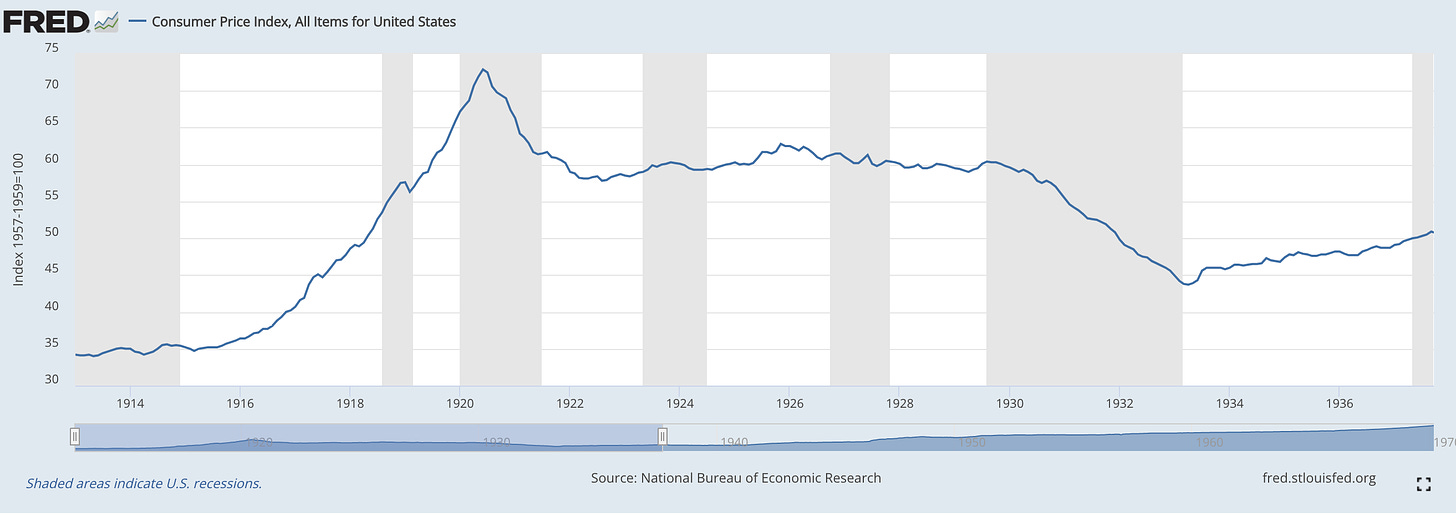

The combination of fiscal and monetary policies had the desired effect in precipitating the most severe deflation in American history, steeper and sharper than during Great Depression.

Source: Fred

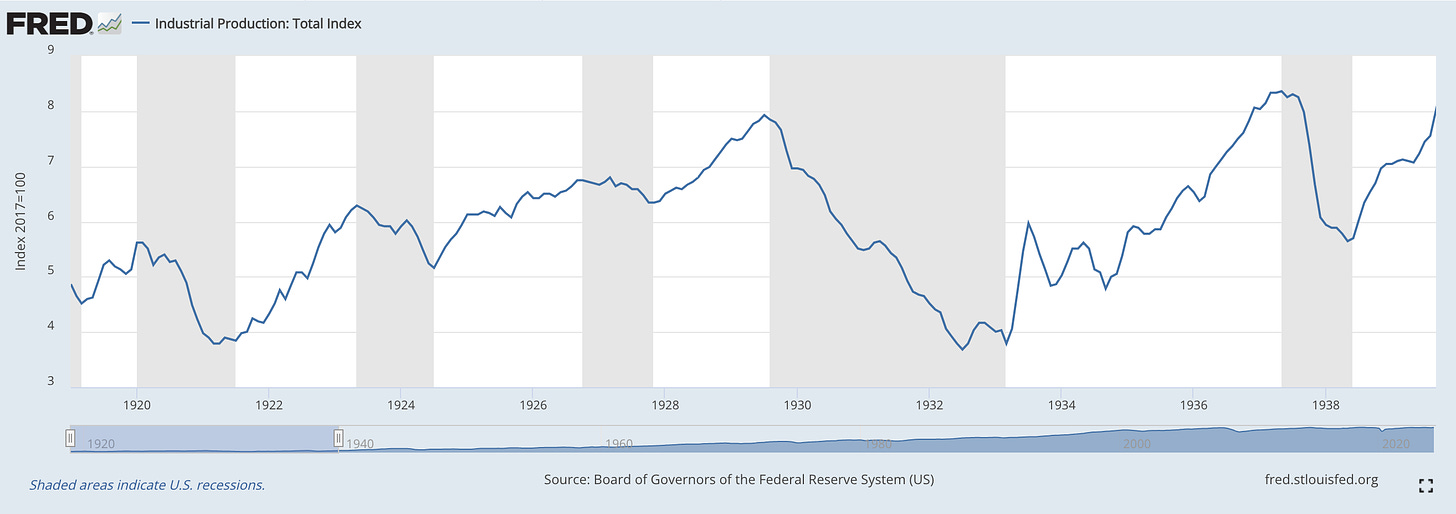

Industrial production slumped.

Source: Fred

Arguably, the postwar recession of 1920-1921 is the most underrated macroeconomic event in the historical record. It was not confined to the USA. Even if it was not articulated as a conscious policy of hegemony, the US was de facto exercising a huge impact on the rest of the world through its economic policy. Across the world, higher Fed interest rates drained gold to the US, tightening local monetary conditions. Even the Weimar Republic saw a sudden deceleration of inflation in 1920. I will say more about this shock in the next installment in this series.

In terms of GDP and growth, the rebound was swift, which is perhaps why the 1920-1921 crisis has disappeared from popular memory. Market-inclined economists are even tempted to celebrate the deflation as a success, restoring economic and social order without causing prolonged economic pain. But the shock was severe and though there was a recovery, the terms of that recovery were set both in America and the rest of the world in a conservative direction.

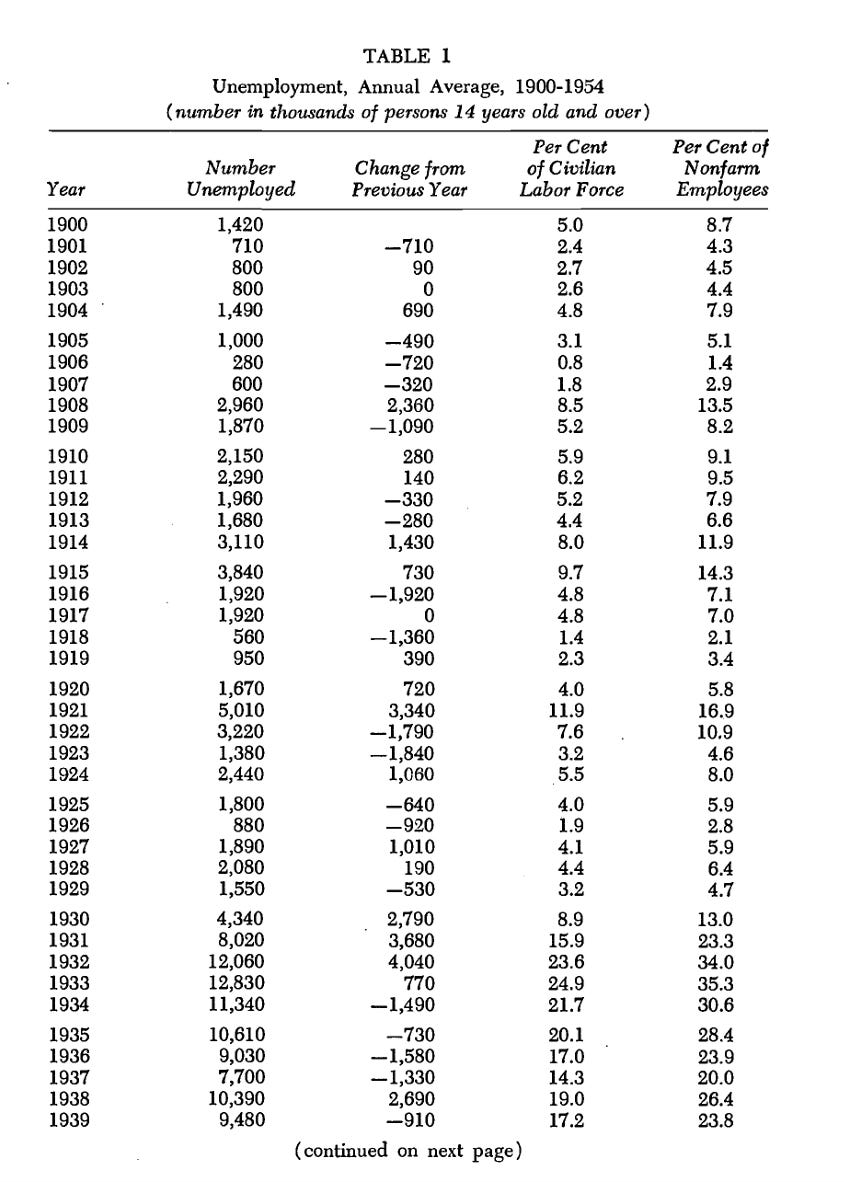

As measured by the data compiled by Stanley Lebergott, unemployment shot up. Over 3.3 million Americans lost their jobs in the space of a few months.

This was a cyclical shock with lasting consequences. As Clara Mattei has outlined in her dramatic history of economics in Italy and Britain, Capital Order, austerity and deflation were a politics of class war. As unemployment surged and the economy slumped, the postwar strike wave was broken. As David Montgomery argued in his classic The Fall of the House of Labour, US organized labour suffered a historic defeat.

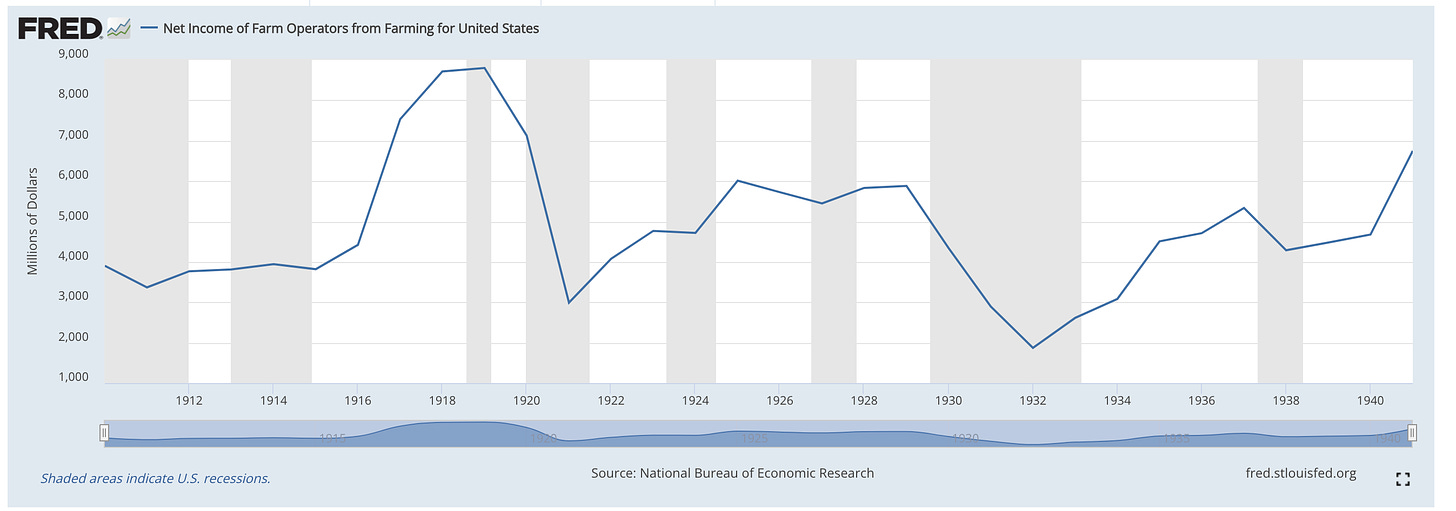

At the same time, as deflation hit home, and commodity prices plummeted, farm incomes crashed from wartime high, more sharply than during the great depression.

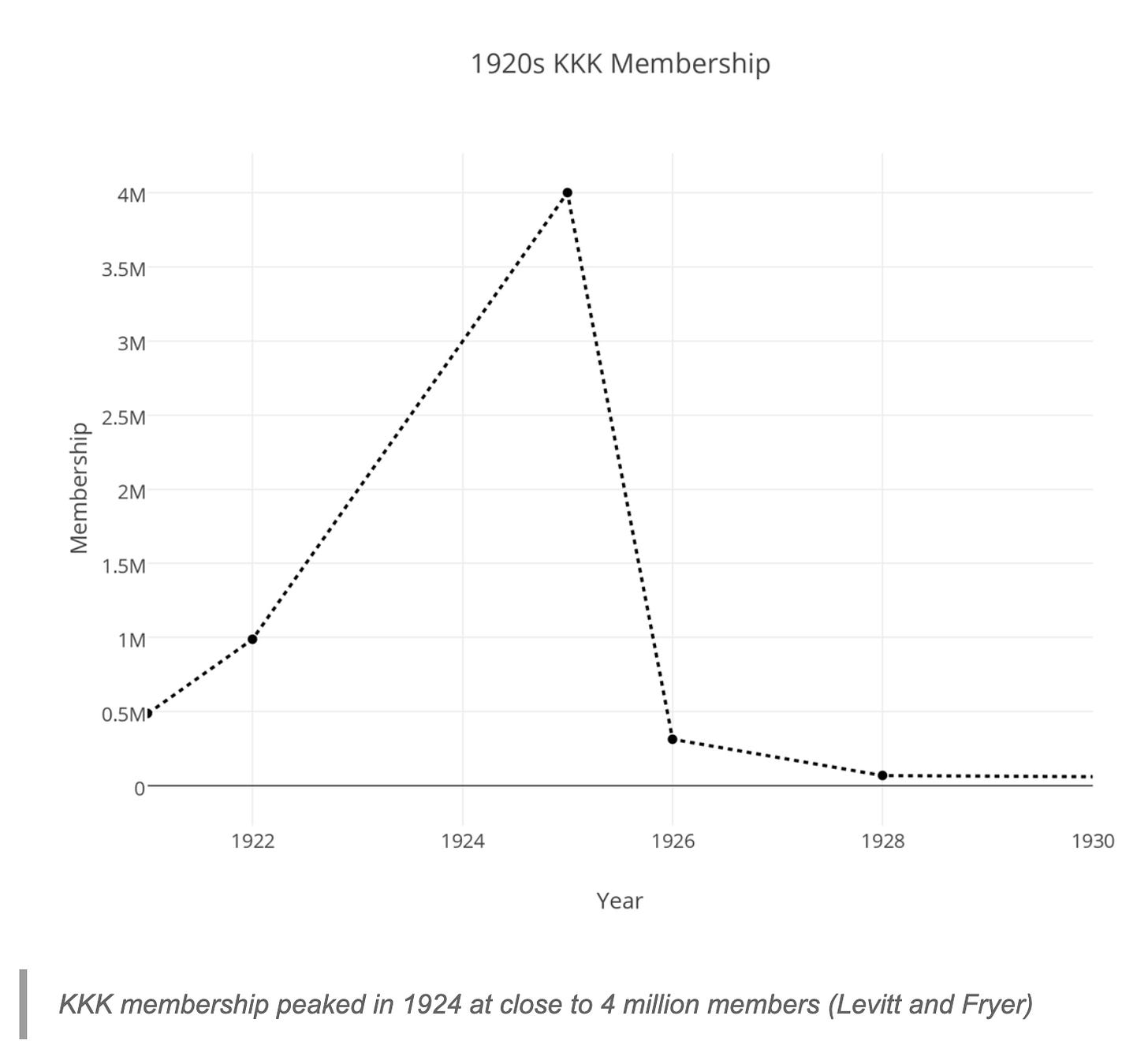

You might ask whether this did not precipitate a right-wing crisis as in Germany and Italy? Was this not the ideal breeding ground for a fascist movement? The answer is that it was. In the USA this took the form of the upsurge in support for the racist secret society, the Ku Klux Klan.

Source: “Hatred and Profit”, Fryer and Levitt, QJE 2012

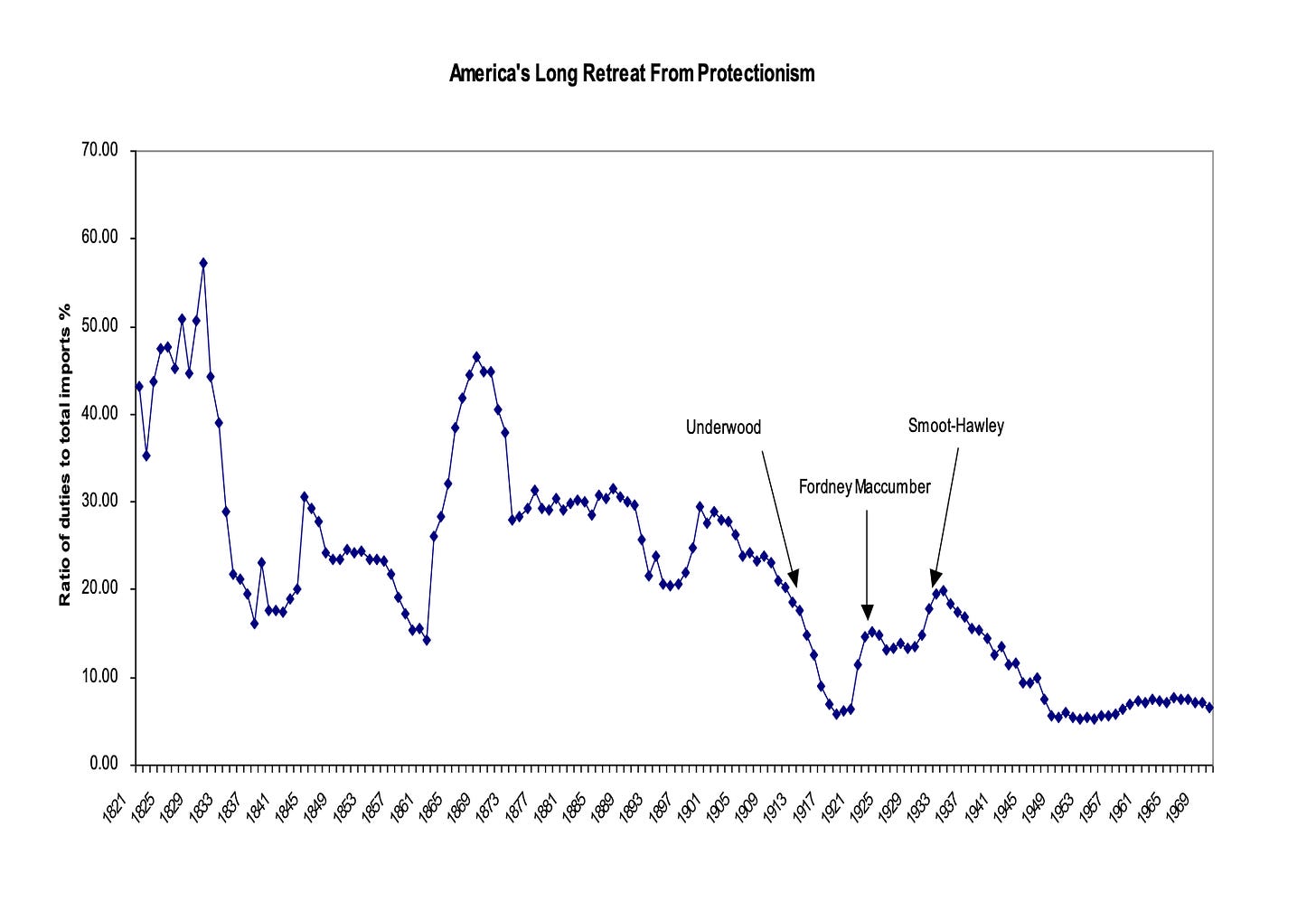

To address the crisis, following the Republican sweep in November 1920 elections, Congress got busy. The recession in business and in farming provided the motivation for a return to protectionism. In May 1921 Congress passed the Emergency Tariff Act reversing the cuts under the Underwood tariff and the Wilson administration preparing the way for the more infamous Smoot-Hawley legislation of the 1930s. Despite the changed circumstances of the world economy created by World War I, America reverted to protectionism.

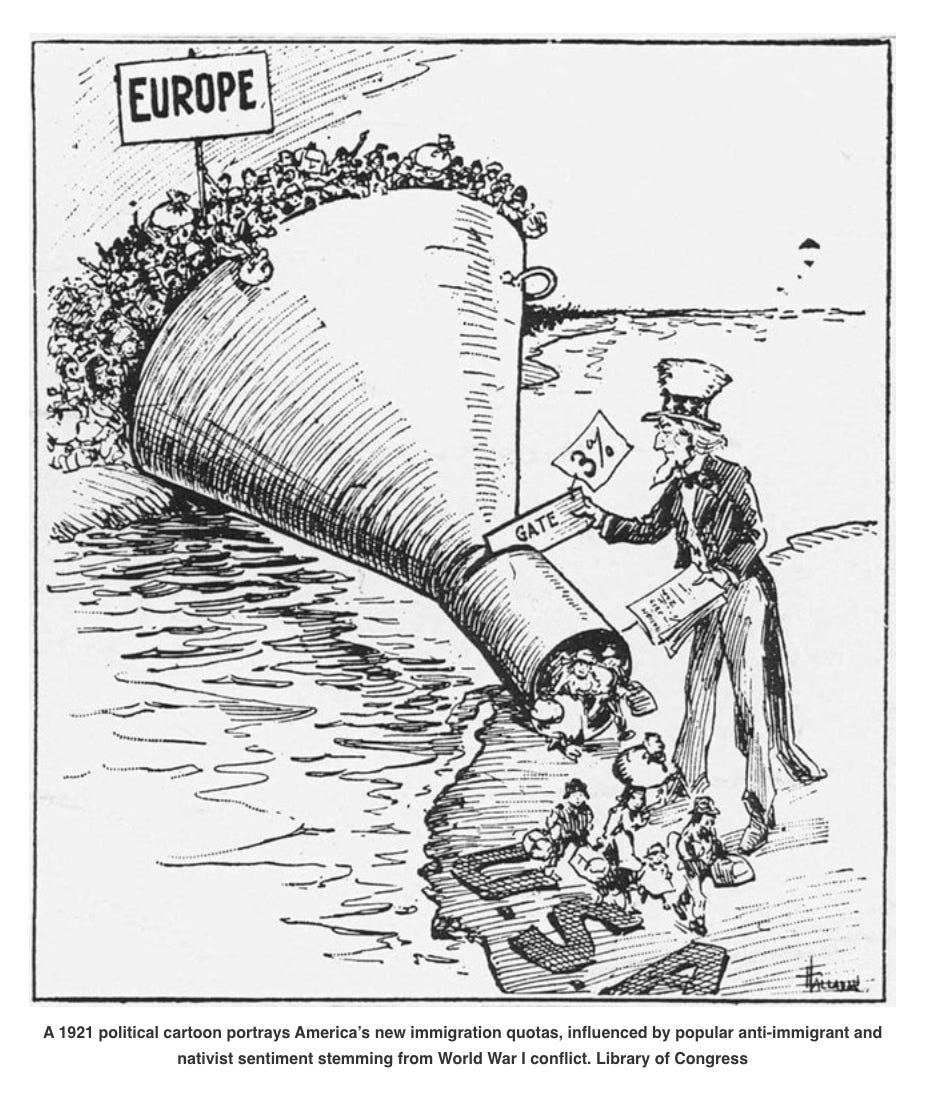

Also in May 1921 also under the sign of “emergency”, Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act which for the first time drastically curbed immigration arrivals from outside the Western Hemisphere. Each country's annual cap was based on 3% of the size of its immigrant population in the United States as of the 1910 Census. The total was limited to 358,000 per year. This set the stage for the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act), which granted immigration visas to 2% of each nationality's total population in the United States as of the 1890 census and capped the annual immigration quota for the rest of the world at 165,000, a 80% reduction from the yearly average before 1914. America’s action triggered similarly restrictive policies in other countries of mass immigration. With the 1921 announcement, the United States signaled the end of the relatively liberal global migration regime of the pre-1914 period. In the subsequent decades, the US social order would stabilize. But “sending countries” now had to absorb “surplus populations” at home.

So, in a world reeling from the effects of World War I, with Russia undergoing civil war and revolution, with much of Asia and the rest of the world in uproar, the United States

absented itself from the League of Nations

shut the door to migration

despite its new position as the world’s creditor, it shut the door to imports

and, as the last major country still propping up the gold standard, it delivered a savage deflationary shock via fiscal and monetary policy.

As I have argued in earlier posts in this series, no country had ever been forced into the position of global centrality that the US de facto came to occupy after 1916. There was no template for the kind of hegemony that this implied.

But, this combination of policies was clearly disastrous and contemporaries both inside and outside the US knew it. As Wilson told the Senate in July 1919, in his typically sentimental manner, they were about to “break the heart of the world”.

And yet the line was hard. When in the spring of 1922 the British Prime Minister Lloyd George made a second effort to organize a true peace conference for Europe at Genoa, the United States again absented itself. The results were dramatic and telling. The British might understand and grasp the scale of the hegemonic problem after World War I, but, as had been clear already during, they did not have the capacity to hold the ring alone. At Genoa, the Soviet and German delegations broke away to sign the notorious Rapallo Treaty, antagonizing the French and setting the course for the final escalation of the European crisis with the Ruhr occupation and hyperinflation in 1923.

As I will lay out in subsequent posts in this series, the US would engage, but only on its own terms. As far as the crucial question of finances and war debts were concerned, those terms were harsh.

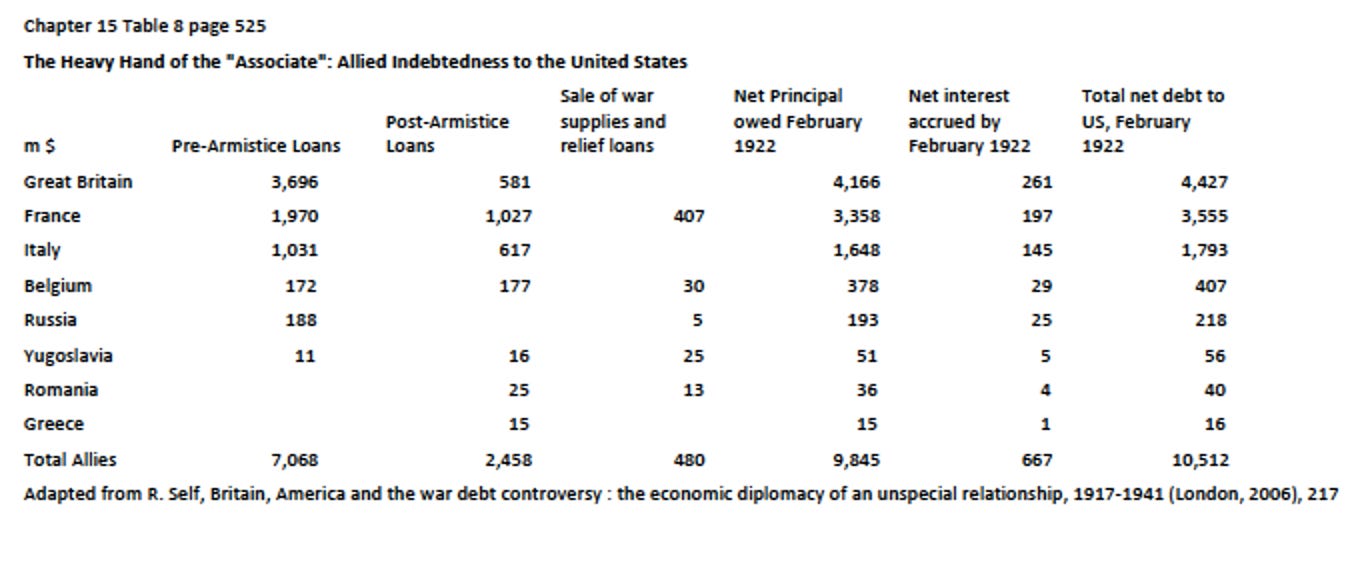

The crucial and entirely novel relationship of dependence created by World War I - the relationship of dependence, which defined a novel and historically unprecedented hegemonic problem - centered on inter-Allied war debt. These were debts owed government-to-government amongst democratic regimes. They were irreducibly political obligations created in the common project of defeating the German-led central powers. They were owed by one country of tax-payers to another.

In the aftermath of the war, and even more so after the Senate’s refusal to ratify Versailles, it was clear that these debts were the key instrument through which the US could constructively shape Europe’s postwar stabilization. Despite their refusal to accept Wilson’s vision of a postwar oder, the key figures in the Republican party were not “isolationists”. They had their own vision of an international order held together through dollar diplomacy and disarmament. Their close allies on Wall Street and in US business were fully aware of the burden that war debts imposed on Europe’s economy, the way in which they jeopardized financial and monetary stabilization and exacerbated the conflict over reparations with Germany.

President Harding’s Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon therefore asked Congress in June 1921 for authorization to set the interest rates and maturity dates, to defer interest payments and to engage in debt swaps. Like European and American experts, Mellon envisioned some kind of comprehensive debt settlement. But the Congressional reaction was definitive and dramatic. First Congress insisted on subjecting the Secretary of the Treasury to Congressional oversight by way of a War Debt Commission that would ensure that the interests of American tax-payers were prioritized above all else. Then, in October 1921, the House voted to prohibit any debt exchange schemes (for instance an exchange of debts owed by France to the US, for reparations debt owed by Germany to France) and also ruled out any debt forgiveness And in early 1922 the Senate stipulated that all loans be repaid within 25 years at an interest rate no less than 4.25 percent. It was this version that became law. (Leffler “The Origins of Republican War Debt Policy, 1921-1923: A Case Study in the Applicability of the Open Door Interpretation”, The Journal of American History 1972).

Explaining his hard line, Democratic Senator Kenneth McKellar of Tennessee put it in stark terms: "We are taxing the American people as they have never been taxed before in the history of the Republic. The burdens of taxation are greater today than ever in its history. If we collect but the interest upon these loans, we will of necessity reduce the taxation upon our own people by one-seventh." This was the crucial point. Given the fact that an enlarged Federal government in the US was a product of the war, the face value of the foreign loans represented more than half of all privately held US federal debt (52 percent) and a remarkable 16 percent of US GDP in 1922. Any significant concession to the wartime “associates” of the USA would, therefore, rebound directly and to a significant degree on US tax-payers. In the state that American society and politics were in, in the wake of World War I, there was no majority that was willing to make that ask. Globally orientated elites might favor a policy of debt reduction for the sake of “the economy”, but with the US public feeling victimized by the financial burden of a war that most had not wanted to be involved in, making substantial concessions was not on the cards. It was not just that the idea of international commitment, or the higher logic of macroeconomics had not yet been socialized. The very idea of the US federal government as a substantial intrusion into ordinary life was as yet unfamiliar. The articulation of hegemonic strategy around notions of “the economy” and “big government” directed towards stabilizing and managing the “world”, all of these elements had yet to be assembled.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook, on which more in a later note. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

I keep the rates as low as substack allows, to ensure that backing Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.

"It was not just that the idea of international commitment, or the higher logic of macroeconomics had not yet been socialized. The very idea of the US federal government as a substantial intrusion into ordinary life was as yet unfamiliar."

I'd say there's a significant portion of American voters who still - a hundred years later - have not accommodated themselves to the idea of "the US federal government as a substantial intrusion into ordinary life." We call these people Republicans.

Our government does millions of things, and accounts for about a third of our GDP, and yet there are still people walking around in a fantasy, believing that - with just the right guy in power - they could take us back to the days before 1917 (Trump has even talked about eliminating the income tax in favor of higher tariffs, a pre-1917 economic policy if there ever was one.)

Then these fantasy-addled people vote Republican, and sometimes even elect Republicans, and the government never gets smaller, only bigger. Naturally, they read this as a betrayal by "the deep state" rather than draw the obvious conclusion that their fantasy is, in fact, a fantasy.

There was a global pandemic in full swing in 1919 - how did that influence the economic situation at the time?