Chartbook #44: The Cross of Gold - populism, democratic iterations and the politics of money

Looking back at an early (de)flation panic.

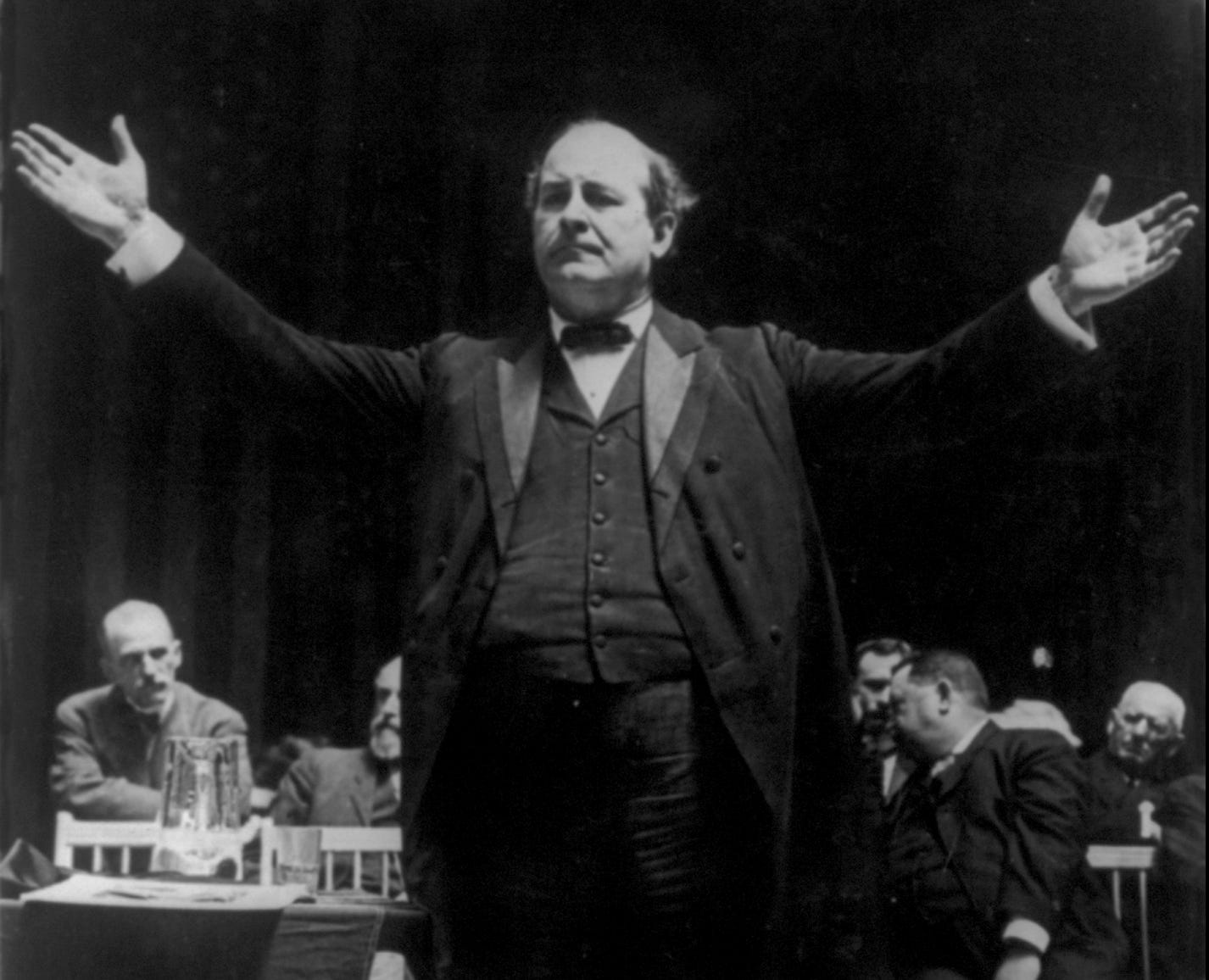

“Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

The address that Nebraska’s William Jennings Bryan delivered at 2 pm on July 9 1896 at the Chicago Convention of the Democratic Party - the “Cross of Gold” speech - is a stunning piece of oratory on the theme of the gold standard and the peril that this rigid monetary system poses to society.

The incident is familiar to anyone with a background in American history. But when I first encountered it, as a European, I was staggered. It struck me as a truly remarkable example of democratic politics engaging with the question of money. It is more than 120 years old, but everyone concerned with monetary politics today should read Bryan’s speech. The full text is here.

Bryan’s oration culminates in these glorious paragraphs:

“If the gold standard is the standard of civilization, why, my friends, should we not have it? So if they come to meet us on that, we can present the history of our nation. More than that, we can tell them this, that they will search the pages of history in vain to find a single instance in which the common people of any land ever declared themselves in favor of a gold standard. They can find where the holders of fixed investments have.

Mr. Carlisle said in 1878 that this was a struggle between the idle holders of idle capital and the struggling masses who produce the wealth and pay the taxes of the country; and my friends, it is simply a question that we shall decide upon which side shall the Democratic Party fight. Upon the side of the idle holders of idle capital, or upon the side of the struggling masses?

…

“There are two ideas of government. There are those who believe that if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous, that their prosperity will leak through on those below. The Democratic idea has been that if you legislate to make the masses prosperous their prosperity will find its way up and through every class that rests upon it.

You come to us and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard. I tell you that the great cities rest upon these broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic. But destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.

….

It is the issue of 1776 over again. Our ancestors, when but 3 million, had the courage to declare their political independence of every other nation upon earth. Shall we, their descendants, when we have grown to 70 million, declare that we are less independent than our forefathers?

….

If they dare to come out in the open field and defend the gold standard as a good thing, we shall fight them to the uttermost, having behind us the producing masses of the nation and the world. Having behind us the commercial interests and the laboring interests and all the toiling masses, we shall answer their demands for a gold standard by saying to them, you shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

*********

Bryan and the populist struggle with the gold standard seem particularly topical because we are, at this moment, debating the economics and politics of inflation and monetary policy. If Modern Monetary Theory insists that monetary sovereignty is there for the taking, in America, that is a claim with a deep history. Not that Bryan was an advocate of modern monetary policy, but he refused to subordinate America’s currency choices to the blackmail of monied interests.

Then there is the meta question. Set against the backdrop of recent history the fact that we are debating monetary policy at all can seem shocking. In the era of the 1980s and 1990s, insulating monetary policy from democracy was a key priority. The point, Rudiger Dornbusch, the influential MIT macroeconomist, liked to insist, was to put an end to “democratic money”.

But for money to be unpolitical, is not the natural order of things. It is the effect of a particular politics, a metapolitics of depoliticization. As Stefan Eich shows us in his forthcoming book, the Currency of Politics, the argument over the politics of money goes back to the ancients. The question should not be - “political money, or not?”. “Democratic money, or not?” The question should be - What kind of politics of money? What kind of democratic money?

The William Jennings Bryan moment rose to the top of stack for my stack in recent weeks, because I am teaching a grad class about the tense relationship between capitalism and democracy in the US and Europe. Our first session was on 1896, William Jennings Bryan and the Cross of Gold Speech. The readings for the session were as follows:

Bryan’s speech, which you can read here.

Rockoff, Hugh. "The" Wizard of Oz" as a monetary allegory." Journal of Political Economy 98.4 (1990): 739-760.

Excerpt from Bensel, Richard Franklin. Passion and Preferences: William Jennings Bryan and the 1896 Democratic Convention. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Bryan, William Jennings. "Has the Election Settled the Money Question?." The North American Review 163.481 (1896): 703-710.

Sanders, Elizabeth. "Farmers and the State in the Progressive Era." The Progressive Era in the USA: 1890–1921. Routledge, 2017. 41-63.

Sanders, Elizabeth. "In Praise of Populism." Cornell International Affairs Review (2009): 11.

Abbott, Philip. "Bryan, Bryan, Bryan, Bryan”: Democratic Theory, Populism, and Philip Roth's “American Trilogy." Canadian Review of American Studies 37.3 (2007): 431-452.

Jäger, Anton, and Noam Maggor. "Phenomenal WorldOctober 1st, 2020 A Popular History of the Fed."

I will tinker with this reading list on future iterations. There is a piece by Milton Friedman, I wished I had included. But this reading list clicked.

To be clear, this is not an American history course. The course is intended for a cosmopolitan mix of students with varied backgrounds interested in the broad theme of capitalism and democracy. The aim of the game is to highlight a series of general issues circling around the politicization of money, how popular mobilization affects the development of economic policy institutions and ways in which politics continuously reactualizes the populist moment.

The majority of the students are not historians, so rather than issues in the American historiography - Who were the populists? Were they racist and exclusionary etc? - what I want to encourage is engagement with the complex entanglement of historicity as such. What I have in mind is Faulkner’s great line that, “the past is never dead. It is not even past”.

The readings are chosen for their content, of course. But I also encourage reading them as historiography and as historical sources, as signifying something about the moment they came out of. That is obvious with regard to the Bryan texts. But it is true also of a blogpost from 2020. This history IS not even past.

******

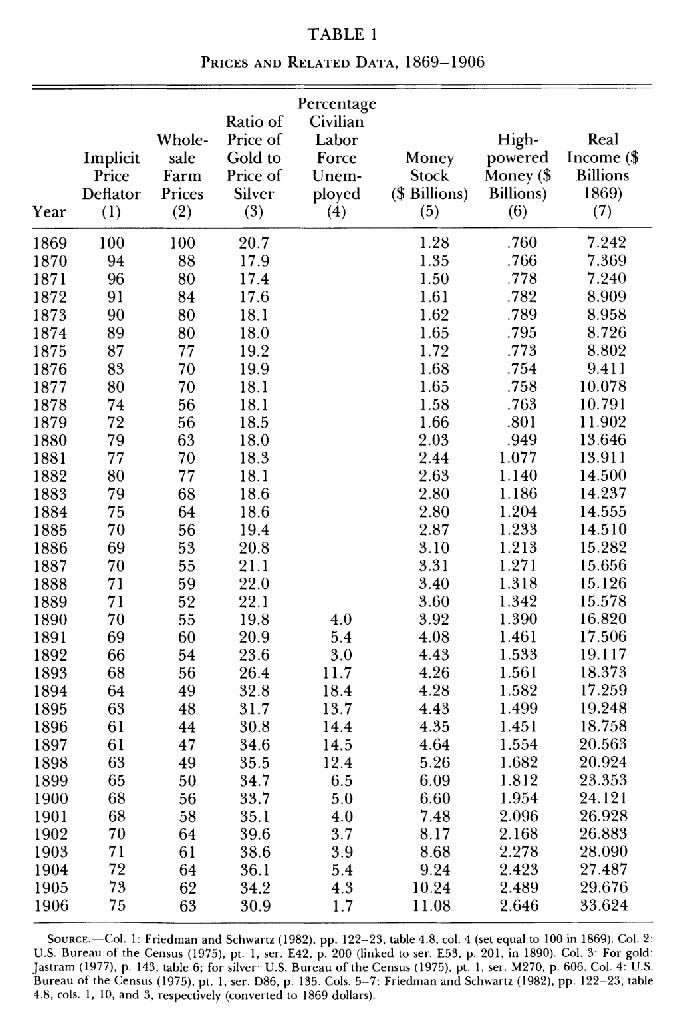

The starting point for the silver agitation was the agonizing deflation that squeezed down on the North Atlantic economy in the late 19th century.

Source: Rockoff (1990)

Wholesale farm prices crashed in the 1870s, then bounced, then crashed, then bounced again and then in the early 1890s fell to their lowest ebb. In 1896, at the moment that Bryan gave his speech, wholesale farm prices were 56 percent below their 1869 level.

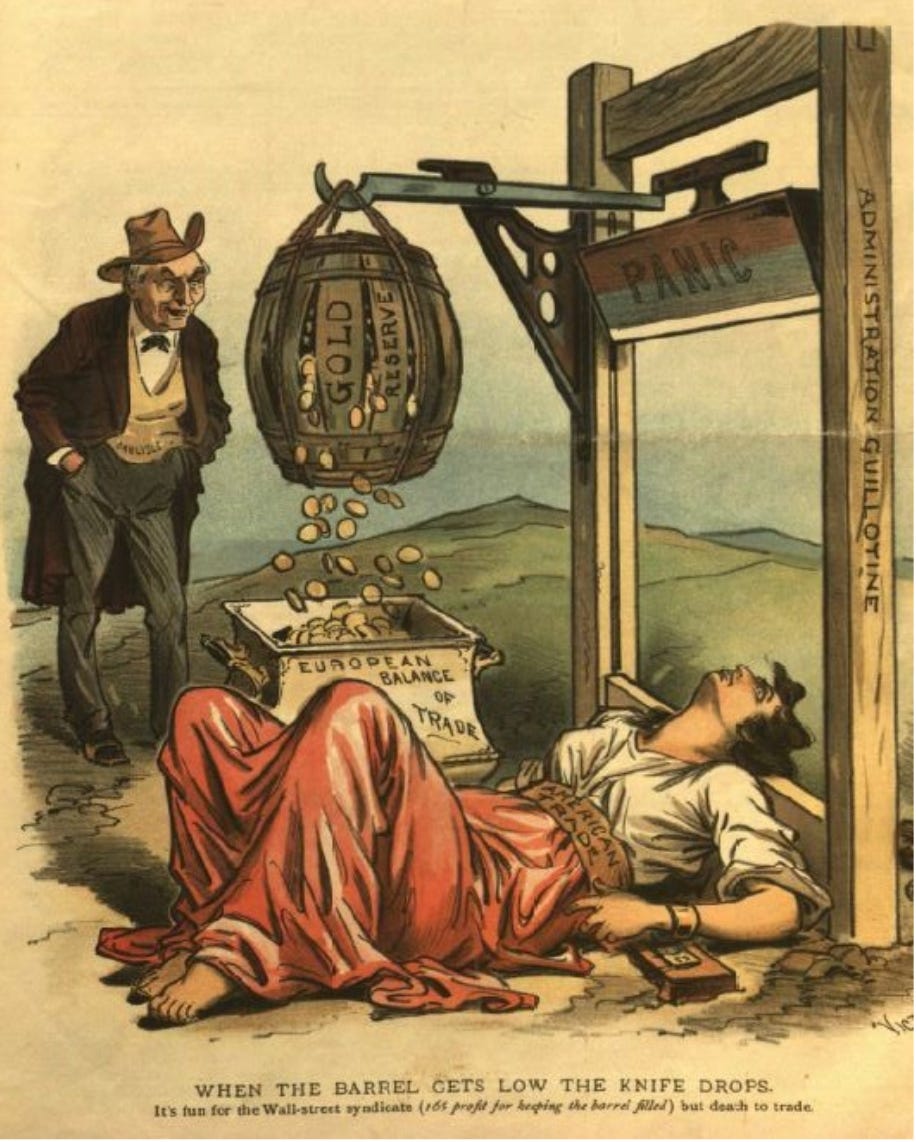

The period 1893-1896 saw the US economy wracked by crisis. Unemployment rocketed into the teens and the survival of the US on the gold standard was in doubt.

Source: Political cartoon from Judge magazine, Oct. 5, 1895. Digitized by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The ultimate reasons for this deflation are complex and disputed. What the populists challenged was the decision to end the monetary chaos of the civil war era in the 1860s by returning to gold, a move completed in 1879. Specifically, what they contested was the Coinage Act of 1873 that ended the right to have silver minted into coin. As Rockoff remarks: “Between 1869 and 1879 the stock of money grew at about 2.6 percent per year and real output at about 5.0 percent per year, so the deflationary pressure from the lack of monetary growth is easy to understand.”

In any case, the point of this session was not so much to answer the question of what caused the late-19th-century deflation, as to show what folks made of it. What agitated the populists, was not only the fact that silver was downgraded relative to gold, but that deflation on this scale crushed debtors. Farm incomes shrank. Mortgages did not.

As Rockoff remarks: “Although the percentage of farmland that was mortgaged was low for the nation as a whole, western farmers … were heavily mortgaged. Kansas had one of the heaviest levels of indebtedness, with 60 percent of taxed acres under mortgage.”

The promise of the free silver movement was that by breaking the link to gold and enabling the minting of silver, an expansion in the money supply would raise prices and ease the pressure on debtors. In 19th-century language, inflation simply meant an expansion in the money supply.

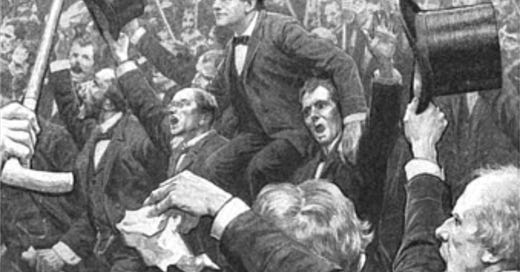

Faced with the bitter hostility of the gold standard bloc, the free silver movement provoked intense controversy. At the Chicago Convention in 1896 there were scenes bordering on riot as advocates of the gold cause and silver took turns to demonstrate their enthusiasm. Richard Bensel in his remarkable microhistory brings the Convention to life in vivid detail. It is akin to an ethnology of late 19th-century American politics.

The Chicago Conference Hall, July 1896

Bryan’s speech sent the Convention into convulsions. So famous was the speech that in 1921, on the 25th anniversary, Bryan made a recording which you can hear on youtube.

As Bensel highlights there was nothing accidental about the sensation that Bryan generated. Bryan rehearsed his delivery. On the eve of his performance, he remarked to his wife and a companion: “So that you both may sleep well tonight, I am going to tell you something. I am the only man who can be nominated. I am what they call “the logic of the situation.””

Bryan’s confidence was rewarded. Whether he was “the logic of the situation” or not, he carried the day and was nominated for the Presidency.

A few months later he narrowly lost the election to McKinley. The gold standard remained safe and the populist cause suffered defeat.

Famously, the struggle was commemorated in the Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum. Rockoff provides a brilliant reading, of how Baum encoded the gold standard battle in his modern fairy tale.

Bryan’s defeat was a turning point in American political history, meaning that the 20th century opened under the sign of “control” rather than popular, democratic mobilization. Twenty years later the moment was commemorated by the anti-war poet Vachel Lindsey in a remarkable sentimental poem.

On Vachel Lindsey’s peculiar poetic and political persona see the Poetry Foundation.

***********

In the aftermath of defeat, Bryan was unbowed. In an essay he published in December 1896 he offered a remarkable diagnosis of the effects of his campaign, a paean to the democratic politics of money and to the importance of throwing open the agenda of economic policy.

“As a rule”, Bryan remarked, “the moneyed interests have looked after our financial policy, while the rest of the people have quarreled over the tariff. The Republican party met in convention last June and attempted to again give the tariff question pre-eminence, but when the Democratic, Populist, and Silver parties agreed in declaring for the free and unlimited coinage of gold and silver at the present legal ratio of 16 to 1, without wait ing for the aid or consent of any other nation, the Republicans found it impossible to confine discussion to the tariff issue. In fact, the silver question soon absorbed public attention to such an extent that it became practically the sole political topic considered throughout the country. People discussed the present legal status of the silver dollar, the various laws affecting silver, the amount of production, the cost of production, etc., etc. To the world at large this nation presented the interesting and inspiring sight of seventy millions of people thinking out their own salvation. Men who had never spoken in public before became public speakers; mothers, wives, and daughters debated the relative merits of the single and the double standards; business partnerships were dissolved on account of political differences ; bosom friends became estranged ; families were divided. In fact we witnessed such activity of mind and stirring of heart as this nation has not witnessed before for thirty years. Foreign newspapers daily reported the progress of the campaign and students of political economy came from Europe to obtain a closer view of the struggle. It is probable that the money question has been studied within the last four months by more people than ever before in all the history of the world simultaneously engaged in its consideration. And what was the result of that study ? Temporary defeat, but permanent gain for the cause of bimetallism.”

It was significant, Bryan remarked, that pro-silver sentiment was strongest where the question had been ventilated for some time, above all in the West and the South.

In the Eastern states, the heart of America’s business economy, debate of the money question had previously been silenced.

“In those States both parties were against free coinage; nearly all the leading news papers were against it; the banking interests were against it ; the corporations were against it; and it was also opposed by those influential members of society who live under the influence of the financial and corporate interests.”

The populist breakthrough at the 1896 convention overturned this repressive consensus. The Democratic Party in the East was reorganized and though the silver cause went down to defeat, it made great strides. And it was vital that this agitation should continue. Having defeated Bryan, the defenders of gold demanded unconditional acceptance of the status quo.

“They complain that agitation disturbs business, and they accuse the advocates of free coinage of stirring up discontent.”

But, Bryan retorted, “(those) who suffer because of the gold standard can hardly be expected to keep quiet and look pleasant while the injury continues. … They too want confidence restored, but it must be a confidence that their condition will be improved not that their lot will be made still harder. Agitation is the only means by which wrong can be redressed under our form of government. The man who denounces agitation simply opposes the discussion of a public question, and the man who attempts to put a stop to the discussion of a public question confesses his hostility to our form of government. In a nation where the people govern, they must be free to consider any subject which concerns their welfare.”

The money question, Bryan insisted,

“transcends in importance any other economic question which can occupy the attention of the American people. When we determine the kind and quantity of money we determine the level of prices, and the level of prices concerns every family in the land.”

Much less well known that the “cross of gold” speech, Bryan’s retrospect on the campaign stands as a powerful justification for a democratic politics of money. It was eloquent and compelling and it forces the question. What was the meaning of populism’s defeat? What consequences did that defeat have at the time?

*******

These are questions of interpretation that are irreducibly political. They echo down to the present.

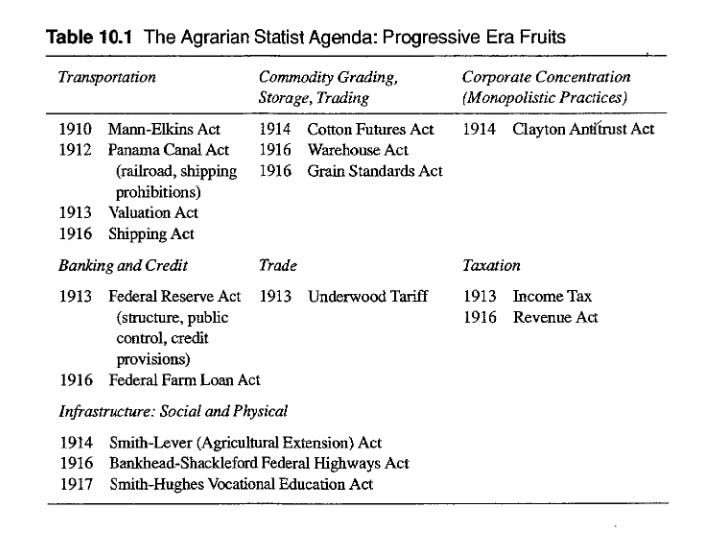

Populism was defeated in 1896, America remained on the gold standard, but the early 20th century is widely seen as having been a period of reform. It was the era of Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. It set the stage for the New Deal. To what political force can those changes be attributed?

One political line characterizes the era as one of progressive triumph. Progressives were middle class reformers dedicated to forestalling the agrarian and grassroots mobilization of populism by means of technocratic reform.

Another current that came to the fore in the aftermath of 1896 was what has been termed “corporate liberalism”. On this view, the force that stood behind the modernization of government was the increasingly consolidated power of American capitalism, expressed in the merger wave.

Both progressive and corporate liberal readings of this historical moment minimize the role of populism and specifically the agrarian interests that it represented. But the populists have their defenders too. The most compelling counter-interpretation is offered by Elizabeth Sanders.

For Sanders the remarkable range of statist measures enacted between 1910 and 1916, often associated with the “New Freedom” agenda, crafted for Woodrow Wilson by Louis Brandeis, was, in fact, in large part the work of Congressional populists. Bryan himself served in Wilson’s administration as Secretary of State, pursuing an agenda of international conciliation in a vain effort to prevent the outbreak of World War I. At home, Wilson’s progressive agenda was in large part the fruit of the agrarian mobilization.

As Sanders lucidly argues, it would be simplistic to imagine that the progressive, the corporate liberal or the populist agenda would simply be carried into government policy. We need to consider a three-way configuration of forces including extra parliamentary pressure, Congressional action and the structures of government themselves.

As has recently been argued by Stefan Link and Naom Maggor, the United States of the late 19th century was a developing nation. The agrarian mobilization of the 1890s cast a long shadow.

The Fed in particular was a product of this balance of forces. The Wall Street lobby had its say, as did progressive technocratic ideas. But the Fed that emerged in 1913, as a public body with a governing board located in Washington DC rather than Wall Street, was viewed with deep suspicion by the financial lobby and denounced as product of meddling populist impulses.

***********

If there is one piece I would swap into the reading list for the session, it is the appreciation of populist monetary economics by Milton Friedman from 1990. Friedman is well known as an exponent of the quantity theory of money. The godfather of the quantity theory in its modern form was Irving Fisher (1867-1947), who began his career at the time of the populist mobilization. Fisher sympathized with the critics of the gold standard. Clearly, adherence to gold did not produce a stable value of money. Instead, money’s value rose inexorably against goods, as prices fell. Tying the value of money to silver as well as gold was a bit like trying to achieve stability by tying too drunks together. Rather than gold or a bimetallic silver-gold standard, Fisher argued for a stabilized “compensated dollar”. With hindsight, however, both Fisher and Friedman were willing to conceded that the populists had a point. The urgent need was for a monetary expansion by whatever means. If the world economy had not been boosted by a rash of gold discoveries in the 1890s, the technological innovations of the period, might well have led even deeper into depression and crisis.

*******

The embrace of populist economics in the course of the later 20th century, is indicative of a broader reevaluation, which in the hands of Elizabeth Sanders amongst others has a political edge. As Sanders remarked in 2009:

“Newspaper and Television commentaries in the United States and Europe abound with references to “outbursts of populism” in United States as a stereotypically American response to economic crisis. Their story lines trivialize historic Populism in the U.S., both its substance and its contribution to financial regulation.” In the wake of 2008 she hoped, against hope, that a reforming Democratic administration might side with the pitchforks against the entrenched interests of finance and push for truly radical reform.

Dodd-Frank was a bitter disappointment. But one can learn from the populists also in defeat. As Bryan remarked about 1896, campaigns to politicize and democratize money cannot be judged only by whether they come first at the polls. They are, as Seyla Benhabib might say, democratic iterations. Part of an ongoing struggle and deliberation that draws recursively on its own history and precedents. If the crisis of 2008 did one thing, it ended the illusion that money could be unpolitical. In the years since, central banking choices have been debated and open to public scrutiny. The level of popular engagement is nowhere near that described, perhaps wishfully by Bryan in 1896. But it is nonetheless novel. And, as the blog post by Jäger and Maggor attests, that process, again and again, recurs to the populist moment.

As Jäger and Maggor remark: "the Populist story gives historical heft to some recently floated reform schemes. Central bank planning might already be here and simply be awaiting democratization, but it is hardly unprecedented. Rather than a historical departure, the democratic empowerment of central banks could fulfill deep-seated democratic aspirations, articulated by farmers, workers, and craftsmen in the turmoil of the first Gilded Age."

This is a very interesting post! My understanding of this era is shaped by Martin Sklar and I've long heard that Sklar although brilliant is a bit off, so naturally I'm interested about what you qua author of The Deluge think about this subject. I didn't know about Elizabeth Sanders & her work but it seems like at least a useful corrective to my Sklar-informed perspective, perhaps simply a refutation.

Would you be willing to share the course syllabus?

I love the historical context you give to current events. Thanks for what you do.