The macrofinancial switchback of COVID-inflation-interest rate hikes has put the global market for fixed-income securities, valued at c $130 trillion, on the rack. The spring of 2023 has seen historically exceptional turbulence, and a sense of foreboding, as other shocks seem to lie ahead. The weakest borrowers have been cut off and some have slid into crisis. As ever, the authorities, above all in the US, have been there to provide a measure of derisking to exposed banks and shadow banks in the core of the system. But what does that mean? Daniela Gabor and I have been going back and forth in recent days on how to characterize this situation.

To make a very complex argument simple, I tend to think that we are in a period of considerable flux. By contrast, Daniele Gabor defends the view that in its core functions the derisking state has if anything been confirmed by recent events. I’ll come back to some of the broader interpretative issues in a future post.

***

In the mean time, the exchanges on twitter have brought to mind that last fall I started a series of Chartbook posts called “Finance & the Polycrisis” that were intended to track the swing in financial markets, particularly bonds and real estate, under the impact of the diverse shocks we have been experiencing since 2020.

The series started with 6 posts.

#1 Nov 12 Finance and the polycrisis (1): What bends? What breaks? What implodes?

#2 Nov 13 The global housing downturn

#3 Nov 15 US Treasuries - how fragile is the world's most important market?

#4 Nov 23 Fed effects & European corporate bond market.

#5 Dec 12 The hunt for the next market fracture.

#6 Dec 19 Africa’s debt crisis

Then, over Christmas and New Year I lost the thread. Christmas trees, inflation, globalization, Ukraine, cocoa occupied my attention. I feel bad that the broader themes of the series dropped out of my mind.

The last real overview was the Jan 3 edition of the Ones and Tooze podcast where Cam and I discussed a range of global financial questions.

Then, in March, financial instability roared back. Chartbook #200 should by rights have been titled Finance and the Polycrisis #7. That was on March 11 Something broke! The Silicon Valley Bank Failure

In that spirit I am rebadging the following posts as part of the series.

#8 March 14 Venture dominance?

#9 March 19 Banking crises, states of exception & the disappointment of sovereignty

And most recently to

#10 April 1 The trillion-dollar rebalancing: A new macrofinancial conjuncture?

Today’s post is #11 in the Finance & the Polycrisis series.

***

Revisiting the series is useful not just as a housekeeping exercise. It brings to mind two of the reasons why I emphasize the novelty of the current situation over the argument for continuity made by Daniela Gabor in our exchange.

The polycrisis we are living in - for me encapsulated in the pandemic-Trump-China-Russia-inflation-climate conjuncture - is a situation of escalating complexity, novelty and radicalism. We have been in the midst of the escalation for a while. One can trace both our current macrofinancial regime and our awareness of the polycrisis back to the 1970s. Indeed, the arms length, depoliticized mode of governance embodied in central-bank-derisked global finance organized around bond markets, was attractive in part because it promised to reduce pressure on politics and states in the face of multiple challenges. But by the same token it is less a “regime” or a particular “form of state” than a constantly evolving series of institutional innovations and improvisations that are subject to both exogenous and endogenous shocks. We are currently in a “hot phase”, which demands not the self-confident operation of familiar mechanisms, but scrambling improvisation and a dramatic readjustment of the horizon of expectations that organize and gives the appearance of coherence to those improvisations.

If you follow market discourse closely, which is the aim of the Chartbook series, the overwhelming impression you come away with is not one of a tight knit group of experts who know what they are doing. But rather the contrary. Practically everywhere you look, you see people who are as knowledgeable as it gets scratching their heads, uncertain not just about what happens next, but about what happened yesterday and how some of the basic mechanisms we take for granted actually work.

Resuming this series on Chartbook I want to emphasize both the first aspect (1) Polycrisis and (2) the collective puzzlement of people at the heart of global finance, who you might assume really understood what was happening.

Three examples from the coverage of the last week.

***

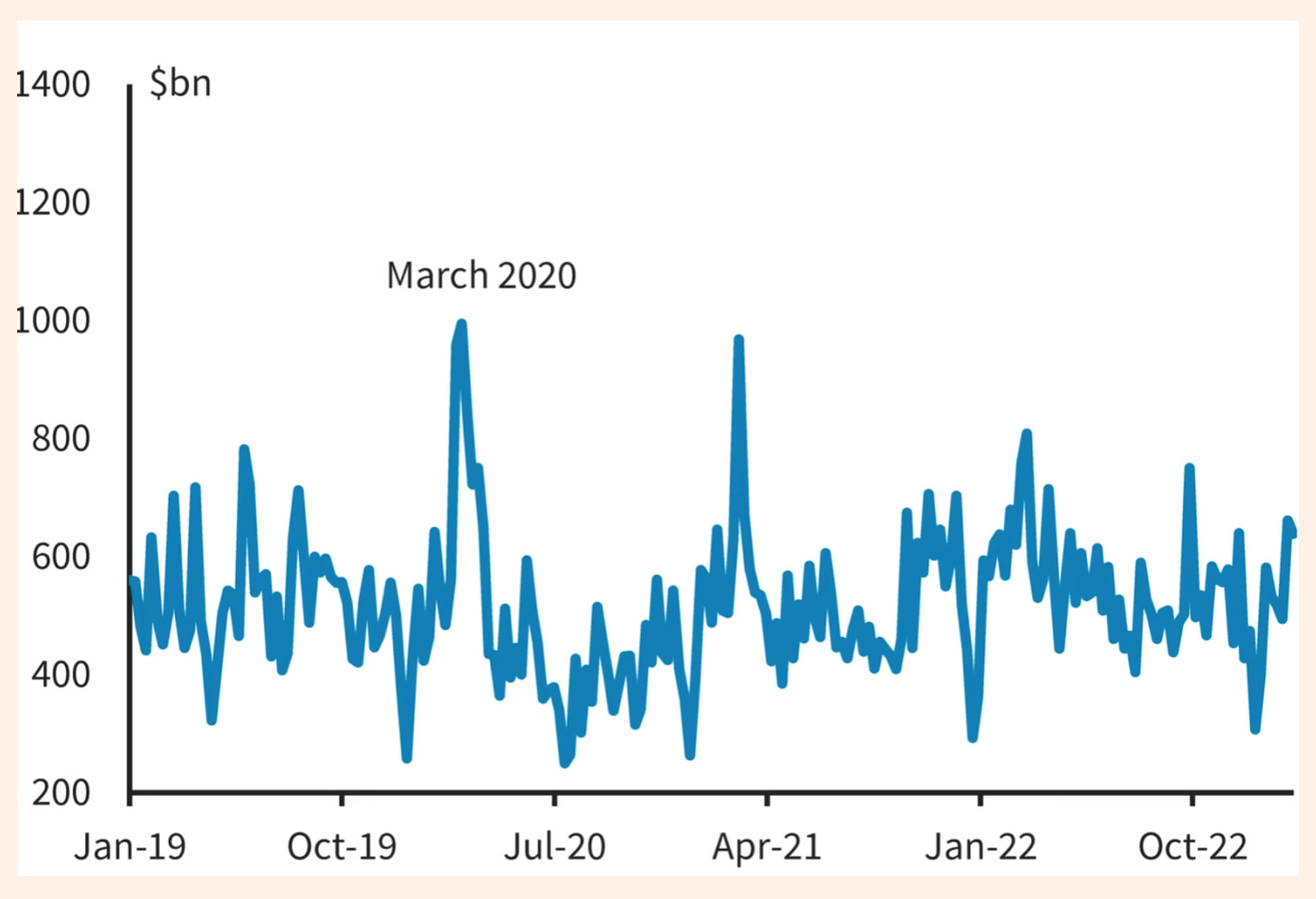

Example 1: A note by Robin Wigglesworth in Alphaville of the FT puzzling, by way of some research by Barclays, over quite how chaotic things were in the US Treasury market in March.

As the screams of agony from macro hedge funds and CTAs have indicated, this month has been, well, mental for the Treasury market. It’s incredible what a small sudden banking crisis can do isn’t it? First, some back-story: A weird anomaly about the US bond market is that Treasuries — arguably the single most important cornerstone of the global financial system — have long been one of the most opaque areas. While dealers have long reported all municipal, corporate or agency bond trades within five minutes to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority — which collects then in “Trace”, or the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine, and disseminates them publicly — Treasuries were long exempt. However, after a wild 2014 “flash rally” in Treasuries painfully exposed how little even regulators see in that market, US government debt has been slowly been forced into Trace. And in a bit of luck, Trace switched from weekly to daily Treasury trading reporting on Feb 13 — just in time for this month’s banking crisis. Barclays has pored through the data, and it’s wild. Daily nominal Treasury volumes spiked to as high as $1.2trn on March 13 — the Monday after Silicon Valley Bank collapsed — and daily volumes have averaged as high as $1tn. To put this in context, that is an even greater spasm of trading than what we saw at the peak of the Covid-triggered market panic in March 2020.

So that is remarkable a. because it happened and b. because this is apparently the first time we could actually know that it did, at least in such detail. But what does it mean?

There has been much ink — real and digital — spilled on concerns over the liquidity of the Treasury market in recent years, some of which on Alphaville. But it seems that despite a trading frenzy that surpassed that of March 2020, bid-ask spreads didn’t balloon nearly as violently this time. …. Does this mean that the Treasury market is not nearly as decrepit as some people have been saying? Probably. But the data — especially those gradually increasing bid-ask spreads even for ultra-liquid on-the-run Treasuries — does show why more work is needed to reinforce the world’s most important financial market.

So, maybe the US Treasury market - the foundation of the global financial system - is less broken than many of us fear. Or maybe not. Of course, we do know from 2020 what happens if things go wrong. The Fed steps in. This is a problem with an obvious solution. But that in turn leaves a legacy in the giant inflated balance sheet.

You can see, perhaps, why I prefer to avoid talking about “regimes” or a “derisiking state”, terms which seem to imply a degree of institutional robustness that reflect what you might call a substantivist conception of power, rather than something more fluid, quicksilver (now you see it and now you don’t) and improvised.

To avoid misunderstanding this is not a “historians” argument for particularity against a social scientists preference for concepts. What is at stake is a conceptual not a disciplinary issue. The question is how we think about knowledge and power in modern history, or modern history and power/knowledge. It is a point of difference which needs much further and deeper exploration in future posts.

***

Example 2: The on-going puzzlement and concern about what happens next in Japan.

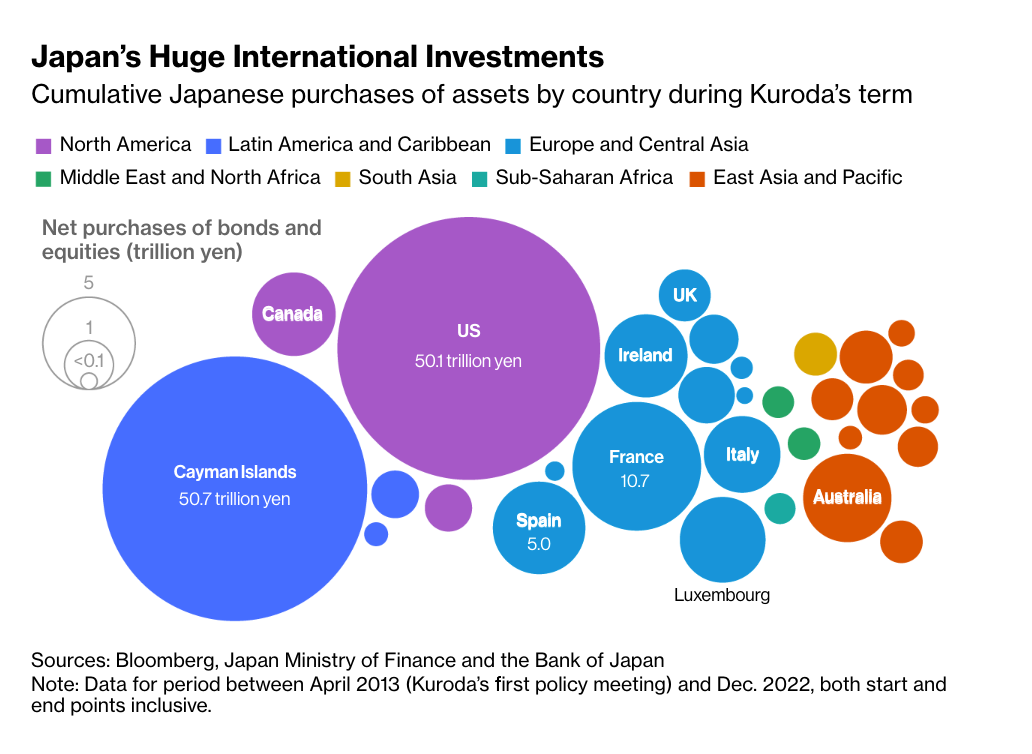

At the beginning of the month the leadership of the Bank of Japan changed hands. Haruhiko Kuroda - the godfather of the biggest bond buying scheme in history - retired to be replaced by Kazuo Ueda. For the occasion Bloomberg ran an excellent round up on the stakes involved in Japan’s monetary policy. Again the headline is striking: A $3 Trillion Threat to Global Financial Markets Looms in Japan

the new governor Ueda … may have little choice but to end the world’s boldest easy-money experiment just as rising interest rates elsewhere are already jolting the international banking sector and threatening financial stability. The stakes are enormous: Japanese investors are the biggest foreign holders of US government bonds and own everything from Brazilian debt to European power stations to bundles of risky loans stateside. An increase in Japan’s borrowing costs threatens to amplify the swings in global bond markets, which are being rocked by the Federal Reserve’s year-long campaign to combat inflation and the new danger of a credit crunch. Against this backdrop, tighter monetary policy by the BOJ is likely to intensify scrutiny of its country’s lenders in the wake of recent bank turmoil in the US and Europe. A change in policy in Japan is “an additional force that is not being appreciated” and “all G-3 economies in one way or the other will be reducing their balance sheets and tightening policy” when it happens, said Jean Boivin, head of the BlackRock Investment Institute and former Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada. “When you control a price and loosen the grip, it can be challenging and messy. We think it’s a big deal what happens next.” The flow reversal is already underway. Japanese investors sold a record amount of overseas debt last year as local yields rose on speculation that the BOJ would normalize policy.

The BOJ’s bond-buying program was a key global anchor both of lower interest rates and the assumption that they would stay that way for the foreseeable future.

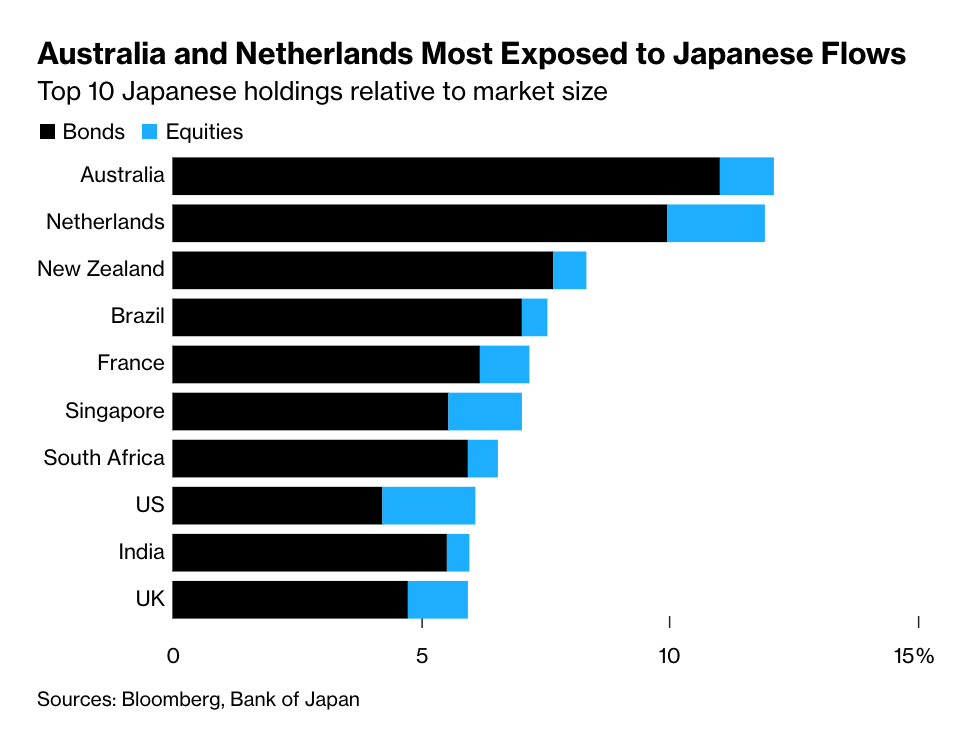

The BOJ has bought 465 trillion yen ($3.55 trillion) of Japanese government bonds since Kuroda implemented quantitative easing a decade ago, according to central bank data, depressing yields and fueling unprecedented distortions in the sovereign debt market. As a result, local funds sold 206 trillion yen of the securities during the period to seek better returns elsewhere. The shift was so seismic that Japanese investors became the biggest holders of Treasuries outside the US as well as owners of about 10% of Australian debt and Dutch bonds. They also own 8% of New Zealand’s securities and 7% of Brazil’s debt, calculations by Bloomberg show. The reach extends to stocks, with Japanese investors having splashed out 54.1 trillion yen on global shares since April 2013. Their holdings of equities are equivalent to between 1% and 2% of the stock markets in the US, Netherlands, Singapore and the UK. Japan’s ultra-low rates were a big reason the yen tumbled to a 32-year low last year, and it has been a top option for income-seeking carry traders to fund purchases of currencies ranging from Brazil’s real to the Indonesian rupiah.

Japanese investors have been burned by the losses suffered by bond investors worldwide. The anticipated turn in BoJ policy adds to the appeal of bringing money home. But when and how will the BoJ initiate its shift in stance? We simply do not know.

As the Bloomberg piece concedes:

To be sure, few are prepared to go all out in betting Ueda will rock the boat once he gets into office. A recent Bloomberg survey showed 41% of BOJ watchers see a tightening step taking place in June, up from 26% in February, while former Japan Vice Finance Minister Eisuke Sakakibara said the BOJ may raise rates by October. A summary of opinions from the BOJ’s March 9-10 meeting showed the central bank remains cautious about executing a policy pivot before achieving its inflation target. And that was even after Japan’s inflation accelerated beyond 4% to set a fresh four-decade high.

The next central bank meeting, Ueda’s first, is scheduled to take place April 27-28.

How to assess this situation? Richard Clarida, who served as Vice Chairman at the Federal Reserve from 2018 to 2022, who is now global economic advisor at Pacific Investment Management Co. remarks:

Ueda “may want to go in the direction to shrink the balance sheet or reinvest the redemptions, but that is not one for day one,” he said, adding Japan’s tightening would be a “historic moment” for markets though it may not be a “driver of global bonds.”

It may or may not be a historic moment. That basic uncertainty about the direction of travel, the sense that policy may be forced to move very large pieces of the global financial puzzle is what suggests to me that what we are seeing, is not just business as usual, but something closer to a conjunctural sea change.

***

Example 3: Developing countries locked out

In recent decades there has been a lot of talk about “development finance” as the high-road to achieving sustainable development. Low-income and developing countries will be incorporated into global financial markets, assisted by various types of “blended” public-private finance, allowing billions in assistance from the advanced economies to be turned into the trillions we all know are necessary for sustainable development. This is what Daniela Gabor calls the “Wall Street consensus”.

It is very hegemonic. It promises big profits for Western investors. But it is also, to a considerable extent, a charade. Not only are the costs and benefits unequally distributed between private investors and tax-payers in both advanced and developing economies. More importantly, the flows of finance enabled by public derisking have been trivial by comparison with the acknowledged need. Judged by its own ambition it has been a crashing failure. The system has come nowhere near enabling trillions of dollars to flow.

Now, as rates shift upwards, another risk is revealed. Once they become reliant on borrowing from bond markets, developing countries can find themselves suddenly locked out, as a result of interest rate movements and risk appetite in the rest of the world.

As Martha Muir writes in the FT.

More than a quarter of emerging market countries have found themselves effectively locked out of international bond markets as recent chaos in the banking sector has prompted investors to shun riskier assets. Even as the effects of the banking sector turmoil recede in developed economies, investors have adopted a “risk off” approach to high-yield debt. This has tipped emerging market countries whose credit status was already shaky into territory where their ability to raise funds is seriously impaired. According to research by Goldman Sachs, around 27 per cent of emerging market sovereigns currently have spreads on yields compared to equivalent US Treasuries of above 9 percentage points, the level at which market access typically becomes restricted. …. Egyptian and Bolivian dollar bonds are among those which have underperformed since the start of the banking panic, with their spreads climbing to 11 and 14 percentage points. Investors say that countries which had plans to issue bonds have avoided coming to market, such as Nigeria and Kenya, whose spreads climbed to 8.95 and 8.4 percentage points respectively in March. … Countries which face restricted access to international debt markets may be forced to turn to the IMF, private market debt sales and currency devaluations. “[Restricted access to debt markets] will push countries to take tough measures at a time where inflation is already high and they’re already struggling with low growth,” said Sara Grut, an emerging markets sovereign credit strategist at Goldman Sachs. “The key question for these countries is, what will be the thing to help them regain market access? One could be that they do very uncomfortable, unpopular reforms, or we see much stronger global growth that improves market sentiment.”

You could say that this shock merely confirms the fact that the global financial architecture is hierarchical and that derisking is a privilege of those in the core. This is true and to that extent you might say, plus ça change. But as manifest as these structural inequalities are, we should not underestimate the element of historical change and the significance of expectations, anchored in narratives, in propelling that change.

Blended finance was the fashion of the early 2000s and early 2010s. It always lived on promise as much as reality. The combination of the modest results actually delivered, followed by the 2014 commodity price shock, COVID, the food price shock of 2022 and now the market pullback of 2023, is enough to induce comprehensive disenchantment. This will not stop the macrofinancial imagination. Currently ,there are efforts to raise excitement around repo markets for African sovereign debt and giant imaginary markets for carbon credits. This imagination matters. It is important in motivating and legitimating action. But, at some point, history does begin to repeat as farce.

***

Does this mean that we are in a new macroeconomic or macrofinancial regime? Cédric Durand in New Left Review’s Sidecar, suggests as much, asking whether we are seeing the end of the hegemony of finance.

To return to the basic conceptual/analytical point, I’m skeptical about any such totalizing, metonymic move. I think our reality is too protean, too dynamic, too explosive to yield to such formulations.

But are the shifts adding up? Is the polycrisis shaking loose the assemblage of improvisations and assumptions we have been living with in recent decades? I think so. That’s the question that this series of posts will continue to track, on the hunch that something is indeed happening.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here:

To overly simplify: I think we’re going through an era of paying for a few decades of unnecessarily, gratuitously low interest rates and off-shoring of jobs. Also complicating things: The Powers That Be are happy with elected officials and their appointees who support a distorted economy that enriches said elite at the expense of everyone else.

Glad to see the polycrisis series gathered together here and tracking. What's on the other side of this "shift" worries me. Particularly as sovereign conflict edges out economic cooperative strategies for growth.