Chartbook 207 Finance & the Polycrisis #10: The trillion-dollar rebalancing: A new macrofinancial conjuncture?

Whats new and whats old in the current conjuncture? I devoted my column this month in the FT to dissecting the forces at work in the recent banking crises and beyond.

What I wanted to push back against was the line of commentary that interprets the current round of banking crises and bailouts as repeating old patterns rather than reflecting a historic sea change in financial markets and policy stance.

Since the piece stirred a flurry of disagreement and quizzical commentary on twitter it seemed worthwhile adding some comments in the newsletter by way of explanation. I include the FT text below in block quotes with further explanation and elaboratorion interspersed.

***

Faced with a rash of banking crises it is tempting to declare, plus ca change. There is nothing more inevitable than death, taxes and bank failures. But what about the bailouts? The publicly subsidised takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS and the hasty extension of guarantees to all SVB’s depositors are just the latest in a recent series of such actions. They suggest that we have entered a new era, one in which thoroughgoing liquidation of financial bubbles is politically unthinkable and so moral hazard and zombie balance sheets pile up.

Both these interpretations are superficially plausible. Put them together and you have a vision of ever larger balance sheets, inevitable crisis and no-less inevitable bailout, opening the path to even greater leverage and risk.

It is fair to say, I think, that this vision is shared by both left and right. I recently heard Cédric Durand espouse a similar line of argument at a EMNP conference at Sapienza in Rome.

But in focusing on the morality play (AT: a word play on moral hazard) of bad bank managers and lax supervision, they mischaracterise the drama we are living through. What defines our current moment is neither the bank failures nor the relatively modest bailouts, but the astonishing macro-financial switchback of 2020-2023. This began with mega-QE in response to the truly unprecedented shock of the Covid-19 lockdowns. The combination of stimulus, supply-chain disruption and Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine unleashed the biggest surge in inflation in half a century, which was met, not with monetary easing but with the most comprehensive tightening of monetary policy since the beginning of the fiat money era.

What I am trying to do here is to distinguish the immediate causes of the recent bank failures (such as appalling liquidity management at SVB) and the consequent bailouts, which are familiar and repetitive, from the broader backdrop, which really isn’t.

The COVID shock was uniquely savage and necessitated a uniquely gigantic central bank intervention. The ensuing inflation was the most dramatic since the early 1980s. The interest rate hike we have seen since 2021 has been the most comprehensive ever. The bond markets last year suffered their worst year on record.

This entire sequence defies previous experience and leaves us without obvious or convincing points of orientation.

This is not a case of “plus ca change” but of polycrisis. We would not be here but for the pandemic. And the central bank response too is novel. They are doing what is necessary to stave off further contagion from SVB, but on rates they are sticking to their guns. Since early 2022 in the face of a market rout the Federal Reserve has shown a resolve few people credited them with. Fed chair Jay Powell even half-hinted that a crisis or two might help to take the steam out of the economy. Certainly, those counting on the Fed to soothe their pain over huge losses on bond portfolios have had a rude awakening.

The crucial point here is that the “Fed Put”, the supposed guarantee by the Fed and other central banks that they would back the markets has been voided.

As it turned out, the Fed’s commitment to the “Put” - an idea that first developed in the late 1980s - had never been tested in an inflationary situation. As a result we had a somewhat exaggerated impression of what became known as “financial dominance” i.e. the idea that the immediate interests of financial markets (rather than longer-term general interest in price stability) drove the Fed.

In 2021, whilst it had its eye on the recovery from COVID, the Fed was slow to raise rates. But when it pivoted to monetary restriction it pivoted fast and hard. If the Fed Put was previously an important assumption underpinning market behavior, and it surely was, it is now gone.

But, one might object, the authorities did step in with expansive new tools to bail out SVB’s depositors. In Chartbook 201 I wrote about “venture dominance”. But venture dominance is exactly that i.e. an important part of business community demanding a local bank bailout. This is a far more limited reaction than the Fed Put. Nor are the recent bank bailouts simply a repetition of earlier episodes.

It makes a difference, it seems to me, whether we are talking, as in 2008, about a comprehensive bailout of the banks that had engulfed themselves in a crisis of their own making. Or, as in 2020, dramatic central bank action to stabilize financial markets whose fragility was exposed by the impact of a pandemic. Or, as in 2023, a limited bailout of the depositors in a medium-sized but well-connected bank whose mismanagement was exposed by a sudden and peculiarly dramatic shift in Fed policy in response to inflation not seen in forty years. These are all bailouts in an extended sense, but not only do they vary in size and the instruments they use, but the shock they are reacting to is different in each case so also is their significance for our interpretation of what some analysts like Danieala Gabor call the “macrofinancial regime”.

In the FT piece I double down on this contrast between the bank bailouts and the monetary policy shock delivered by the Fed, by making a quantitative comparison.

Containing the fallout from SVB and Credit Suisse does involve some element of public subsidy, but those transfers are tiny in comparison with the trillion-dollar balance sheet shift from bond investor to bond issuers triggered by the post-Covid pile-up of inflation and interest rate hikes.

To be clear, this is not intended as a moral judgement. My point is not that the little bit of sugar (bailouts) is small beer by comparison with the pain inflicted through inflation-interest rates on the poor old banks. I make the comparison in support of the claim that the situation we are in is novel and not the repetition of previous bailouts. The historically noteworthy thing here is the monetary policy shock, which many thought the Fed lacked the nerve to deliver.

In the banking system the effect of this shock is visible in the now much-discussed losses on the bank balance sheets. These are mainly unrealized but notionally huge. Some estimates put them in excess of $2 trillion.

They are as large as they are because banks loaded up as much as they did after 2020 on fixed-income assets another underrated shift in the macrofinancial regime.

You can of course maintain that given the measures taken to prop up SVB and the derisking approach to every other aspect of policy, such as green industrial policy, which puts finance at the center of public policy, we are still in the same macrofinancial regime as ever. But, at the very least, we have to acknowledge that we had no way of knowing beforehand how the regime would operate in the face of a price surge. The Fed has clearly and brutally signaled its priorities. It will hike rates even if things break and tidy up the mess afterwards. That might change if a reallybig bank is in trouble. But they clearly believe that since 2008 things have changed and the big banks are now resilient enough. Whether this is true or not remains to be seen but it points to continuous change and modification within the macrofinancial regime, tested by shocks and modified by political interventions (as in the loosening. of banking regulation in 2018 which exempted SVB).

****

I could have left it there. Perhaps I should have. But, instead, I decided to extend the argument.

I’ve been waiting for some time for someone to write about the impact on the value of government debt of the double whammy of inflation and interest rate hikes. I was in part prompted to write my FT op ed by the fact that David Beckworth took up the theme in Barrons.

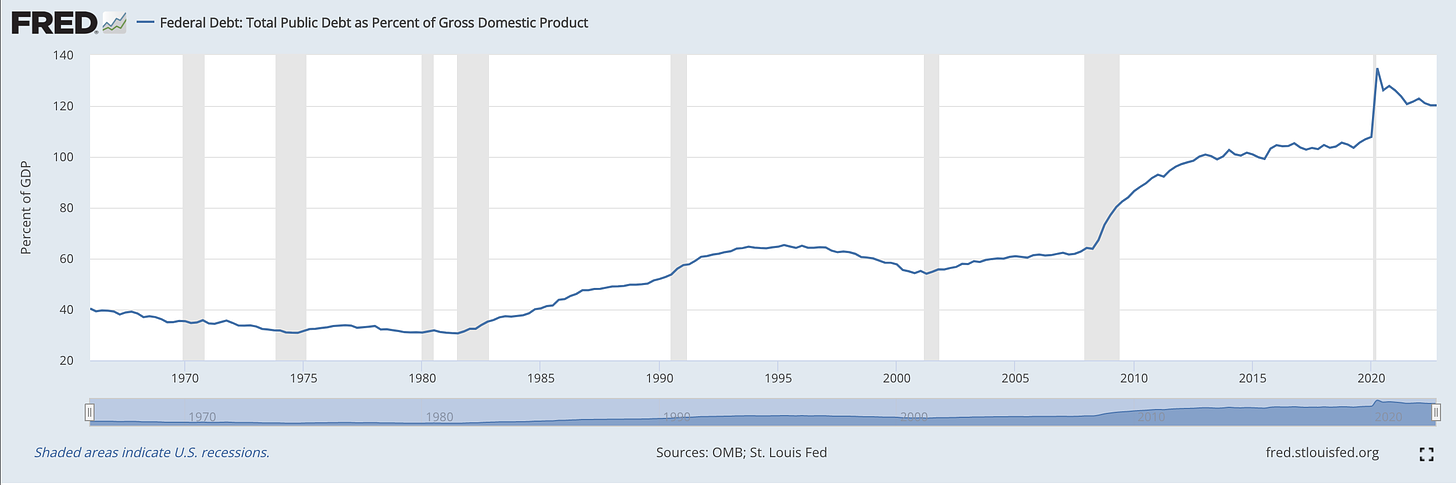

As David Beckworth has pointed out, in the US the ratio of public debt to GDP has plummeted by more than 20 percentage points from its pandemic peak. This spectacular balance sheet shift between debtors and creditors is happening as a result of three forces: the rebound in real output following the Covid shock, the rise in prices and wages which inflates nominal GDP, and the downward revaluation of the stock of bonds as a result of higher interest rates.

This paragraph in my FT piece turned out to be particularly controversial with folks who are deeply invested in the question of how to value debt stocks. Not everyone reading this newsletter may share this passion, so feel free to skip the following pargaraph.

It is controversial to claim that the revaluation of Treasuries and other bonds happening in the market due to the interest rate hike - the revaluation that is marked as an unrealized loss on the balance sheets of banks - really amounts to a transfer of wealth from debtors to creditors. After all, regardless of the market valuation of Treasuries, the taxpayer still has to service the debt and bear the interest burden. If they were to issue new debt to repay the outstanding bonds, the Treasury would do so at the higher interest rates now prevailing, which would negate the purpose of the repayment. The best answer, in defense of counting the debt reduction as real, is to imagine taxpayers actually paying tax with a view to repaying the debts by buying them outright and retiring them. If they did that following the interest rate hike they would realize a gain because purchasing the debt would be cheaper. Critics of the idea respond by pointing out that government debt is not generally repaid, but rolled over into new debt. This may be true, but the logic of the tax-repayment scenario seems sound and as a notional value it corresponds rather neatly to the notional losses on the balance sheet of the banks.

In any case, even if you use more conventional accounting. and focus simply on the surge in nominal gdp relative to national debt - nominal gdp being real gdp adjusted for inflation - it is clear that something very unusual is going on with the US public balance sheet.

In the last sixty years there has never been such a sharp or contrary development of the debt to gdp level as we have seen since 2020: first surging, then plunging and then continuing to tail off, despite continuing large deficits. Debt to gdp is now 15 percentage points lower than it was in Q2 2022 even as debt has increased by $5 trillion. This is because of the dramatic rebound of real output and the surge of prices.

In Europe, using entirely conventional debt accounting, we see a similar effect.

As recently as 2021 we were still worried about how we would cope with insuperable debt levels in a world of secular stagnation and chronic low inflation. Now the nominal GDP of debt-ridden Italy is increasing so fast that, to the third quarter of 2022, its debt-to-GDP ratio fell year on year by almost 7 per cent.

The idea that you can “inflate away” debt is a pretty common place historical observation. This is happening to a modest degree. But here too we must be careful. People who know a lot about bond market point out that permanently higher inflation may reduce the real value of the principal, but because it necessitates higher nominal interest rates, it drives up the burden of debt service. So, it is important to add at this point that my working assumption is that inflation will prove to be transitory. So what we are experiencing is a one-off shock to the price level, after which inflation will subside and rates will come down. What will remain is the reduction in the real value of the debt as expressed in the debt to gdp ratio.

As the FT column continues:

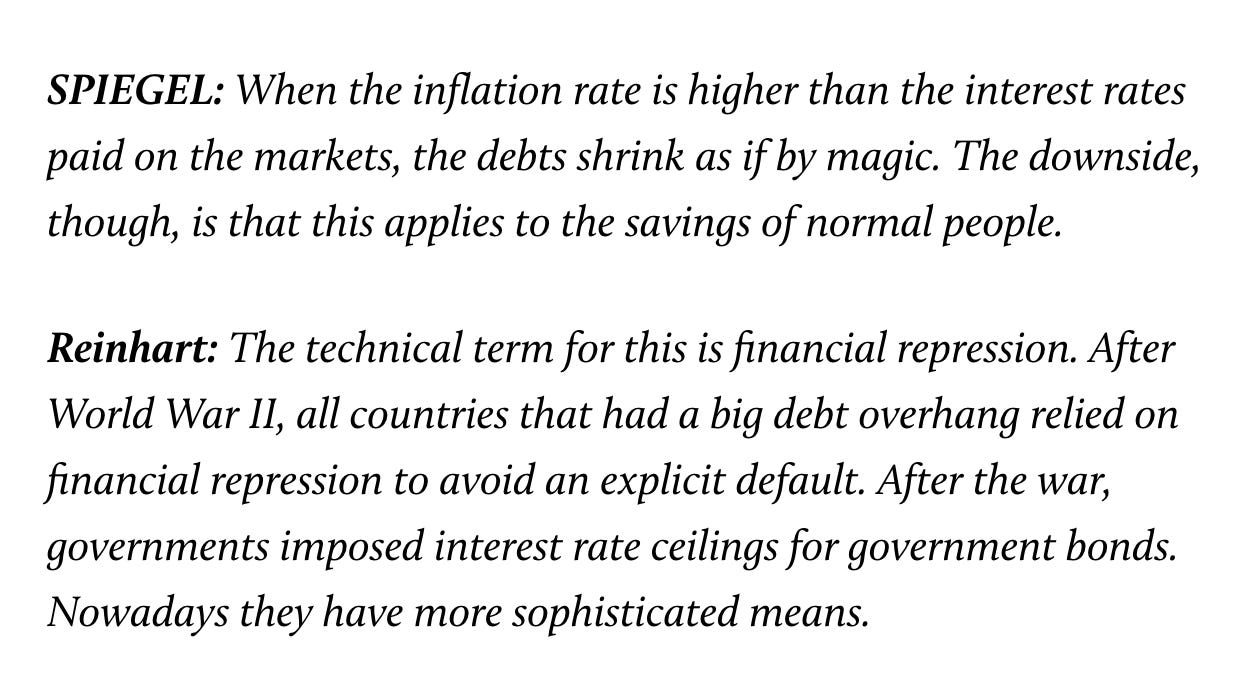

Though no one wants to be seen to be celebrating the inflationary wave, we are, beneath a decent veil of silence, living through one of the most dramatic and powerful episodes of financial repression ever.

This is the next moment in this short piece, in which I managed to upset some readers.

“Financial repression”, is, as they say in German, a Reizwort. If you know a lot of financial history you know that it was a pejorative term invented to describe a situation in which savers and lenders had the screws put on them by borrowers. This is an excellent summary by Jeremy Smith.

In the FT piece I used the term in the way that has, as Smith documents, become common place in financial talk. He quotes, disapprovingly, an interview with Carmen Reinhart in which she gives what I take to be the usual shorthand definition.

To avoid associating myself with a politics that is not mine, rather than saying “we are living through one of the most dramatic and powerful episodes of financial repression ever”, I might have better put my point as follows.

But, in any case, if I exaggerate the care for ‘financial repression” it is not to bemoan the fate of creditors, but rather wishful thinking on my part. I’m all in favor of financial repression. It seems evident to me that if high debt to gdp ratios are a problem, the way to deal with that problem is a combination of redistributive taxation on income and wealth and moderate bouts of unanticipated inflation of the kind we have seen since the second half of 2021.

***

Anyway, by this point some of my friends were losing patience with the tone of the article. “First Tooze is saying that the pain from the Fed is so much worse than the bailouts and now he is saying that the poor old financiers are suffering repression”.

Again, this imputes moral purpose than I intended. My intention rather, was to join. up the dots between the now well-known problem of unrealized balance sheet losses, interest rate hikes, inflation and public debt burdens. This is why the FT piece continues as follows:

Now the nominal GDP of debt-ridden Italy is increasing so fast that, to the third quarter of 2022, its debt-to-GDP ratio fell year on year by almost 7 per cent. Though no one wants to be seen to be celebrating the inflationary wave, we are, beneath a decent veil of silence, living through one of the most dramatic and powerful episodes of financial repression ever.

This is what lies behind the trillions of dollars in unrealised losses on the balance sheets of financial institutions around the world.

I then add a further link in the chain, which is the state of central bank balance sheets. They too are suffering book losses on their bond holdings. The central banks bought those bonds from private banks in exchange for reserves. The central banks now pay elevated rates of interest on those reserves. But if those bonds were on the balance sheets of banks, the unrealized losses in the private sector would be even greater.

The figure would be even greater were it not for the fact that central banks, thanks to QE, are also big holders of government debt and are thus sharing the paper losses.

So this is the central point. The novelty of our situation is that we are seeing trillion-dollar repricing on balance sheets all around and this is more telling than the latest rash of bank failures and bailouts.

Beyond the narrative of feckless banks and bailout-happy regulators, the truly systemic question is how we see our financial institutions through this giant trillion-dollar rebalancing. That is what will define this historical episode.

***

Again, I could have left it there. Perhaps I should have. But I had managed to compress the foregoing into 650 words. So, hey, I had another 150 words to play with. What else could I pack in?

(1) We can add a very important caveat:

Though debtors benefit from inflation and the revaluation of debts, they need to brace for the surging costs of debt service. Those who did not stretch the maturity of their obligations in the era of low rates now face an interest rate cliff.

That doesn’t seem to have satisfied the skeptics, but at least it was there.

(2) With 100 words left, I return to those debt to gdp ratios, spell out some of the political implications and rile up the readers one more time:

But if we can adjust to higher debt service and avoid a rash of bank crises, the one-off shock to the price level (NB one-off shock NOT persistently higher inflation) opens up unexpected fiscal space.

“Fiscal space”? This was the final straw.

How on earth can you can say that an increase in interest rates increases fiscal space? Obviously, higher interest rates by themselves don’t - see caveat (1) above - BUT it seems hard to argue with the idea that a one-off fall in the debt-to-gdp does improve your fiscal situation.

This is not to say that I subscribe wholeheartedly to the idea of “fiscal space”. It is a highly conventional construct at best. But it is an influential construct. And, whatever we take fiscal space to be, the debt to gdp ratio is one of its defining parameter. So, if rather than continuing to rise, your debt to gdp ratio falls. Or if you are in a situation where you can run large deficits and the ratio does not go up, then you gain an unexpected degree of freedom.

So, if the lower debt to gdp ratio does confer a degree of freedom, the question is what to do with it. In conclusion I return (1) to what I take to be the starting point - pandemic/polycrisis

We must use this (“fiscal space”) wisely. We need public investment so as to escape the reactive cycle we are currently locked in and to begin anticipating the challenges of the polycrisis, whether in public health, climate change or destabilising geopolitics.

(2) to a wider view of the distributional question and its implications

We must also provide relief to that part of society which is least well equipped to handle these financially-turbulent times. Those in the bottom half of income and wealth distribution are bystanders in the great balance sheet reshuffle. They hold few if any financial assets and pay relatively little tax. They have lived the drama of Covid and its aftermath as a shock to jobs and cost of living crisis. Unlike bond holders or investors, their interest are not represented by lobbyists. Their households are not too big to fail. But if those who run the system imagine they can be ignored, that they are not systemically important, those elites should not be surprised by the strike waves and populist backlash coming their way.

The key point I wanted to make here is that there is a distributional politics that refers to stocks/balance sheets (debtors v. creditors) as well as distributional politics that refers to flows (income, spending). At least half the population in any capitalist society has no financial wealth to speak of and pays relatively little tax and thus has little at stake in the distributional politics of balance sheets. But we should go on connecting the dots. If you gain a degree of freedom on the balance sheet, consider what options it might open up not just for asset accumulation (investment) but also for the flows i.e. various types of payments.

***

So let me restate the thesis.

We are going through a series of heterogeneous shocks which force policy reactions for which there is no obvious historical precedent - polycrisis.

Every domain of society, economy and politics is affected - health care, defense, tech, energy, and finance amongst others.

The financial apparatus is an important piece of the whole, but we live in an age of financialization as much as we do in an age of big tech, biopower, and mounting great power confrontation between China and the US … One could go on. These sectors intersect and interact. The financial system both receives and delivers shocks. No one sector currently dominates.

The financial system or regime is fraught with power plays between powerful and diverse financial interests, the state apparatus and politics. Whether this is a settled regime is an open question. If we can meaningfully talk of a macrofinancial regime, it includes assumptions about the Fed’s reaction function.

The central bank is relatively autonomous, as it demonstrated both in its slow response to inflation and then in going in hard and fast. In 2022 the Fed invalidated the Fed Put as an operative assumption.

I don’t think they did so in a fit of panic or absent-mindedness. I do not subscribe to the “mistake view” on Fed policy. I think they took a considered risk in prioritizing labour market recovery in 2021. That has paid off. Did they underestimate the inflation risk? Perhaps. They certainly took a risk. Were they aware that this exposed fixed income to the possibility of a huge repricing? Clearly, they were. That is what it means to invalidate the Fed Put.

The hike in 2022 has had a dramatic impact on balance sheets. The Fed Put is gone. Whether Treasuries can any longer be considered a safe asset in Gorton’s terms. is surely open to question. As a credit risk yes. But in terms of rates and pricing, surely not. Along with the end of the Fed Put this would seem to imply a significant shift in macrofinancial regime. And we are not done yet. Bonds were first in line. Real estate may be next.

Weaker banks were exposed and as usual the authorities were forced to step in to avoid systemic damage. But that does not demonstrate financial dominance so much as the necessary buttressing and clean up necessary to enable the Fed to continue the main thrust of policy, which is the interest rate hike. Worth half-decent regulation the whole mess could have been avoided. Of course sloppy regulation is not an accident. It is endogenously produced. But SVB is egregious.

“Venture dominance” mattered at the margin in making the authorities more likely to bail out the SVB depositors than depositors in another bank of similar size. It is a bigger deal than the crypto bust and FTX. But all told it was a minor flanking skirmish in a bigger battle in which the Fed is demonstrating not subservience but, for want of a better word, autonomy.

Is there something to rescue for a progressive policy view? To that a qualified yes. The cunning of history has delivered something akin to financial repression. The real thing would be preferable, but you make the best of what the game gives you.

We should use the rapid pace of nominal gdp growth to enable both longer-term policy and short-term support for those hardest hit by the cost of living crisis.

Should we call this a new macrofinancial regime. That would be to go too far. But how about calling it a new macrofinancial conjuncture?

I owe thanks to all the folks whose head-scratching and argument caused me to think this through.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here:

Without detracting from this thread, there is another trillion Dollar imbalance hiding in plain sight: the US current account deficit. Cracks in the support mechanism that sustain it are increasingly evident. In trade, the number of countries bypassing US Dollar settlement are growing: Brazil this week indicated a willingness to start receiving Renminbi for at least its exports to China. In capital, Greater Arabia is visibly recycling a larger part of its trade surplus towards capital investment in East Asia.

Currently the US accounts for 60% to 65% of ALL current account deficits being run worldwide...and thus, for the Dollar to 'hold', the US must also run 60% to 65% of the world's capital account surpluses. But for how much longer?

Your column points to a Trillion Dollar imbalance WITHIN the Dollar World. I highlight a Trillion Dollar imbalance BETWEEN the Dollar World and the Rest. The two are not disconnected, especially since your imbalance has brutally highlighted the fact that the so-called RISK FREE RATE is anything but. (Was it ever thus?). The surplus runners of the world have noted the US's Achilles Heel with alarm.

Fragility in one world will exacerbate fragility in the other.

In regards to Silicon Valley Bank (California) and Signature Bank (New York), getting rid of the bad actors by imposing what amounts to lifetime bans on employment in the financial services industry would be the appropriate response to the moral hazard problem, where CEOs like Gregory Becker were clearly out of their depth. They, and their closest associates and allies within that industry need to find other, less ruminative employment. No working at banks, or businesses that banks rely on. The industry is shot through and through with conflicts of interest. The result will be fewer buccaneers and more people who behave like operators of nuclear power plants.

It's been far too easy for people to enrich themselves by taking on unfathomable risk in which they had virtually no skin in the game. It is a matter of record that Becker and his management team were repeatedly admonished by Fed regulators that they were treading on thin ice, and that their portfolio of long-term maturity dates (read: longer than years) Treasury bonds rendered their reserves vulnerable to a bank run, especially when more than 97 percent of their depositors owned accounts far in excess of the standard $250,000 maximum on deposit that would be guaranteed by the FDIC. SVB managers were using this business model to pad their personal wealth by being the 'go-to' guys in the Silicon Valley startup community. Their quest to build their personal wealth was always their primary concern. The real moral hazard was allowing these people to remain at the helm, knowing that they were indifferent to the risks they were taking.

So I say, don't let them ever get closer to a bank than an ATM machine. The banking system is a de facto public utility, so treat it that way. Scalability counts, and risk increases geometrically with size.