Chartbook #203 Finance & the polycrisis #9 Banking crises, states of exception & the disappointment of sovereignty - a roundup of last week.

This Sunday is looking like it will be a very stressful day for anyone involved in the financial markets. As I hit “publish” on this newsletter, negotiators are still haggling over the future of Credit Suisse, once a top ten global bank. As Bloomberg reported, bond traders at Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have canceled their weekend plans. For corporate and other bonds they make over the counter deals. Markets will open in Asia, early-evening of Sunday on the East Coast, at which point, the forest fire of uncertainty and contagion will again begin circling the globe. Or it will not. It depends on what happens in Switzerland.

The next 12 hours matter.

Switzerland is preparing to use emergency measures to fast-track the takeover by UBS of Credit Suisse, according to three people familiar with the situation … Under Swiss rules, UBS would typically have to give shareholders six weeks to consult on the acquisition, which would combine Switzerland’s two biggest lenders. Three people briefed on the situation said UBS had indicated that emergency measures would be used so that it could skip the consultation period and pass the deal without a shareholder vote. … Switzerland’s regulator Finma did not immediately respond to requests for comment. The Swiss central bank, Credit Suisse and UBS declined to comment. The Swiss National Bank and regulator Finma have told international counterparts that they regard a deal with UBS as the only option to arrest a collapse in confidence in Credit Suisse … The Swiss cabinet met for an emergency meeting on Saturday evening to discuss the future of Credit Suisse. The cabinet assembled in the finance ministry in Bern for a series of presentations from government officials, the Swiss National Bank, the market regulator Finma, and representatives of the banking sector.”

Not only do rules have to be suspended, UBS is also demanding that someone else, in this case the tax-payer, take on some of the risks lurking in Credit Suisse’s accounts. As Bloomberg and Reuters reports:

UBS is asking the Swiss government to take on certain legal costs and potential future losses in any deal, said the people, with a Reuters report putting the figure at about $6 billion. The complex discussions over what would be the first combination of two global systemically important banks since the financial crisis have seen Swiss and US authorities weigh in …

The deal-making over Credit Suisse is, in short, a classic case of sovereignty exercised through declaring an exception. This is the logic of Carl Schmitt that Cameron and I touch on in the podcast this week, which you can listen to here.

As I argued in Crashed, this can appear as a dramatic assertion of power, but it arises under conditions which, in fact, change its meaning. Who exercises sovereignty at the moment of a bank bailout like this? Is it the authorities who choose to suspend the rules, or some other force, “the markets”, that force the hands of regulators? Who is “the markets”? And can that force of market pressure really be described as sovereign? Is that not to impute too much subjectivity to it, too much by way of “decision-making”? The harassed bond traders who are canceling their tennis games this weekend, no doubt feel that they are the hunted rather than the hunters. That too may be a matter of journalistic emplotment. Apparently some banks, including Deutsche Bank, are hoping to act the role of the sharks, snapping up attractive portions of the Credit Suisse carcass. And, gruesome and suspenseful as it is, can one really say that this scene is exceptional? Is it not an (irregularly) recurring feature of financial capitalism - SNAFU?

Furthermore, before we get too carried away with Schmittian talk of sovereignty, let us acknowledge that what the Swiss regulators are exercising is a distinctly limited form of power. They are not, as far as we know, forcing UBS to buy Credit Suisse. UBS can walk away, as the various banks considering a purchase of Lehman did in September 2008.

The memories of 2008 are still with us in 2023. As Bloomberg notes:

UBS’s chairman knows a crisis. Colm Kelleher, who took his current role less than a year ago, was Morgan Stanley’s chief financial officer during the financial crisis of 2008. The 65-year-old helped orchestrate an emergency investment from Japan’s Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc. that, along with state assistance, kept the US bank afloat. He then helped oversee Morgan Stanley’s investment bank as it sought to win back clients lost in the panic. He retired from the firm in 2019 and joined UBS with the goal of replicating the success of Morgan Stanley’s strategy of scaling up in wealth management to win over investors.

For the Swiss financial “elite”, including figures like Philipp Hildebrand, formerly of the Swiss National Bank, now Vice-chair at Blackrock, there must be eerie echoes of that earlier crisis, when the question was not who would buy Credit Suisse, but whether Credit Suisse or anyone else would be interested in snapping up parts of UBS.

Meanwhile, this week on the other side of the Atlantic, another model of bank-crisis containment was exercised in relation to mid-sized US lender First Republic. Here the other banks - led apparently by Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan - organized themselves to resist the depositor run by making a symbolic show of support for First Republic. The authorities were involved but on the sidelines. There was stigma attached to any direct involvement. As the FT reports:

“The officials were supportive and wanted it to work, but . . . we are not getting anything special,” an industry person briefed on the talks said. “We did not get a wink and a nod.” “The government was well aware but this [plan] was created outside of government. It would have been tainted by the involvement of government,”

The stress in the US financial system last week was, by any measure, serious. As Daniela Gabor noted:

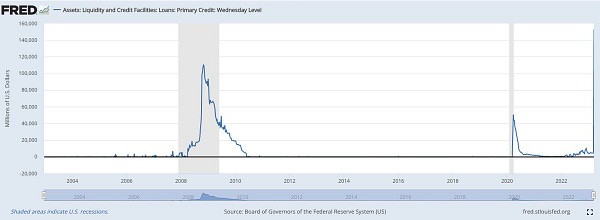

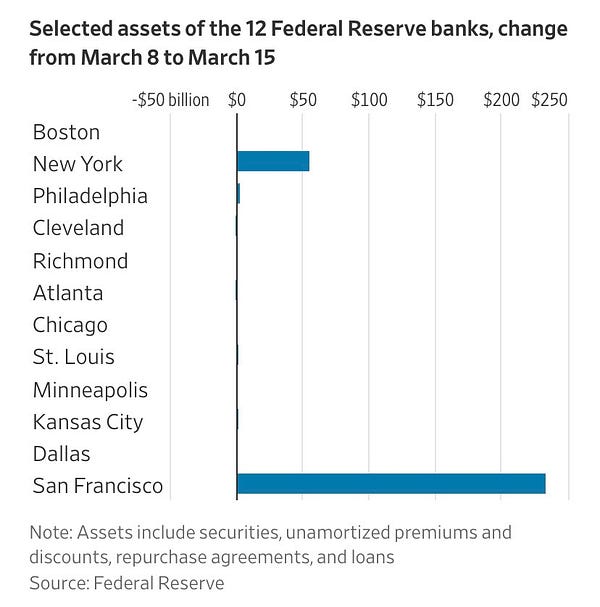

Unsurprisingly, unlike in 2008 much of the emergency lending from the Fed was concentrated in California, not New York.

The most important market in which the uncertainty and fear made itself felt was the market for US Treasuries. It did so in what may seem like a paradoxical way:

One of the underlying frailties of the global banking system right now, are the unrealized losses on bonds incurred by banks as a result of central banks hiking interest rates to combat inflation. As interest rates have gone up, bond prices have gone down. This is bad news, if billions in depositor-withdrawals force you to sell the bonds thus “realizing” the loss. But, if you are not in dire straights, if you are not selling off your portfolio in fire sales, where do you run if the financial world seems to be falling apart (again)? The safe place to run to is … yup … government bonds. They are safe. The market is liquid. Plus, they are cheap right now!

So, a crisis that was triggered in part by bond prices going down, led investors to run into bonds and drive prices back up. A panglossian friend of the markets might say that this is the self-equilibrating invisible hand at work. This is not how it felt last week:

As Katie Martin reports in the FT what dominated the scene was the sheer violence of the market reaction:

On Monday this week (March 13), the most important market in the world went, to use the technical term, completely bananas. Government bonds have a habit of rallying when the going gets tough, which it indisputably did when Silicon Valley Bank imploded. So a jump in US Treasury debt prices off the back of this makes sense. The turmoil prompted nervous investors to look for a safer hidey hole. … But there are bond rallies and there are bond rallies. This time, the market reaction in Treasuries was nothing short of apocalyptic. Two-year Treasury notes, the most sensitive instrument in the debt market to the outlook for interest rates, rocketed higher in price. Yields dropped by an eye-popping 0.56 percentage points, having already dropped by 0.31 percentage points the previous Friday. To put Monday’s move in context, it represents a bigger shock than in March 2020 — not a vintage period for global markets. It was bigger than on any day in the financial crisis in 2008 (ditto). You have to go back to Black Monday of 1987 to find anything more severe.

This points both to the scale of the shock and to the uncertainty that rules in the US Treasury markets. Price movements were as extreme as they were in part because the market was thin, with big gaps between bid and ask prices.

As JP Morgan remarks in a research note:

… liquidity conditions (in the Treasury market) remain relatively impaired, indicating that any fundamental or technically-driven flow is likely to exaggerate moves in yields. Indeed, Treasury market depth remains depressed, at levels last seen in the middle of March 2020, during the worst of the COVID-19 crisis (Exhibit 6). Importantly, this decline in liquidity is broad-based in nature, though it is notable that front-end depth has fallen to new lows (Exhibit 7). While this indicates liquidity is impaired, we do not see Treasury market functioning as being compromised to the extent we observed this time three years ago. Indeed, as we’ve highlighted multiple times in recent months, this illiquidity has been rooted in uncertainty over the path for monetary policy.

On Wednesday, the action in parts of the interest-rate market was so extreme that trading had to be briefly suspended, an emergency safeguard that does not require an sovereign decision by regulators, but is built into so-called “circuit breakers”.

***

What one is left with is the impression of a financial system that is in the limit highly dependent either on emergency action by public bodies, or concerted action by big capitalists interests, that may or may not be coordinated, overtly or tacitly, by the authorities, a coordination facilitated by the fact that everyone knows everyone else:

Interestingly, in the US of all places, moments like this unleash fire storms of debate, notably amongst law professors interested in political economy, about the need to redesign the system of money, banking and finance from the ground up. When it comes to matters of banking, whatever the history and actual experience, there is a radical, not to say utopian strain that survives in America, the heartland of global finance. You can follow their thinking in widely discussed technical proposals for banking regulation and insurance (for instance by Bob Hockett and Saule Omarova) and op-eds (Menand and Ricks) but also on twitter in enormously complex and learned threads that have snaked through the last week.

The key people to follow are:

Who is debating with:

And Nathan Tankus, the odd one out as a non-law school professor, who publishes one of the most interesting (non-Substack) newsletters on all things finance, money and banking - Notes on the Crisis.

It would be worth exploring how and why this radicalism on law, money and finance flourishes in the US, alongside the brutal resilience of bailout capitalism. It is tempting to suggest that the spectacular Minskyian-logic of America’s boom-bust-bailout political economy, which Yakov Feygin identified so precisely, incites against itself a radical imagination. Given the emergency steps being taken, it can hardly be denied that things could obviously be fundamentally different. The “system” such as it is, clearly relies for its continuation on ad hoc interventions. And yet, the moment of radical sovereignty proves disappointing. The incumbent power and wealth exhibit not just resilience, but extremely powerful dynamism, far more than the lame duck contenders in Europe. The Schmittian moment of sovereignty is false. It never arrives for the radical reformists either. So the dialectic continues, without resolution.

In any case, in providing a platform for these debate, in moments like this Twitter (even its current form) more than proves its worth.

***

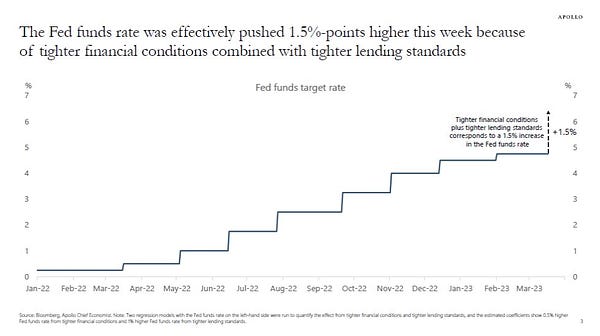

Meanwhile, if your main focus is the real economy and the impact of this shock, the effect is clearly negative:

One “channel of transmission” to watch is the tight nexus between small banks and their lending both to consumers and real estate, especially commercial real estate (CRE). As JP Morgan notes, in aggregate, almost $2tn of CRE loans are held at smaller banks, while around $0.8tn are held at larger ones.

As JP Morgan comments: “if this credit contraction channel halts small bank loan growth—which was recently increasing over $500bn a year—without large banks picking up the slack, we could see 0.5-1.0% shaved off of realized GDP over about a year.” This reinforces JP Morgan’s prediction of a recession in the US in the coming year.

So, you heard it from JP Morgan, unless the big banks grow their lending at the expense of small banks it will be the economy that pays the price. An interesting call for the Fed in the coming week ahead!

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters and receive the full Top Links emails several times per week, click here: