Good morning. This is the third and final leg of Chartbook’s latest collaboration with Unhedged, the FT’s indispensable markets newsletter put out by robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

If you want to read more from Unhedged -- usually for Premium FT subscribers only -- you can get a free 30 day trial by clicking here. The newsletter is also now available as a standalone subscription for just $8 per month. I find it essential reading.

If you want to hear more Chartbook, click one of the options here:

Unhedged: the investment case for India (Robert and Ethan)

The war in Gaza has deepened the pattern of global polarisation that first became painfully apparent with the invasion of Ukraine. As President Joe Biden arrived in Israel yesterday, Vladimir Putin appeared in Beijing. Increasingly, China, Russia and Iran look like an authoritarian bloc that exists in tension with America, the western democracies and their allies. The most important country standing between these poles is India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is often counted among the world’s nationalist strong men, yet he leads the world’s largest democracy. The leaders of the democratic world, as they edge away from China, are keen to deepen ties with India, as both a strategic counterweight and economic partner. At the same moment, global corporations and investors are making an analogous turn to India. From an FT editorial over the summer:

India’s rising role in the global economy is indeed becoming harder to ignore. In April, it overtook China as the world’s most populous country. The IMF expects its economy to grow over 6 per cent this year, and investors increasingly see the country as an alternative to China . . . Optimism surrounding India’s economy has boomed this year. Its stock market has surged as foreign investors have bought into its national growth story. Multinationals have shown an interest in shifting manufacturing to the country as part of “China plus one” diversification strategies

The idea that India can neatly replace China as a growth market, manufacturing hub and destination for capital faces both political and economic question marks, as exemplified by the and Adani crisis on the economic/corporate side and, on the geopolitical side, the assassination in Canada of Sikh separatist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, which Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau has alleged was instigated by Indian agents. For democratic governments and profit-seeking investors, the question is the same: how reliable a partner is India? The China disappointment is fresh in investors’ minds. What looked like a growing, liberalising, outward-facing economy disappointed on all three fronts, leaving global capital nursing poor returns. Might this pattern be repeated in India?

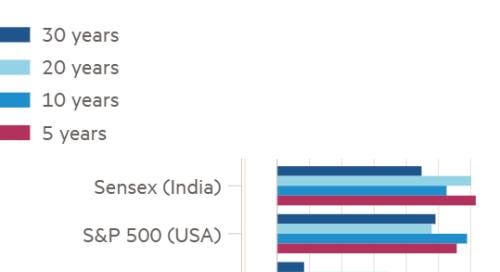

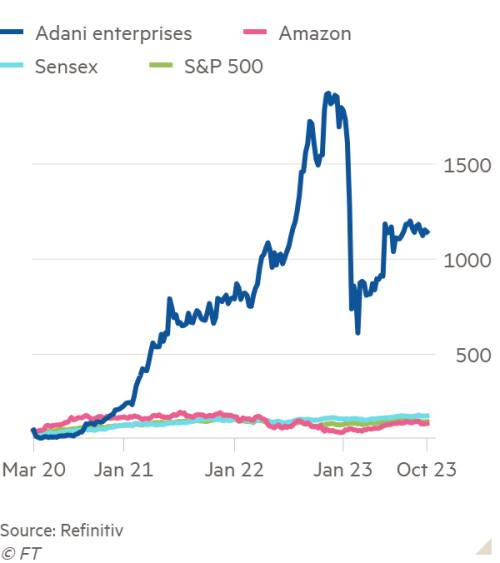

At Unhedged, our focus is the investment story. It is powerfully appealing. It has been a bitterly disappointing decade for emerging market investors. But the desire to allocate a meaningful slice of portfolios to the emerging world, as a source of both diversification and growth, remains. And the strongest reason for weighing this slice towards India is not just that the country has averaged real GDP growth of more than 6 per cent a year for the past 30 years; that growth has also translated into stock market returns in a way that China’s growth, for example, has not. Over the past 30, 20, 10 and five years, the Sensex has performed as well or better than the S&P 500, leaving other big markets far behind:

The other great stock market

India’s growth story is built on its remarkable increase in total factor productivity, the economy’s ability to generate output from a given amount of labour and capital. Aditya Suresh of Macquarie notes that TFP’s contribution to headline growth has averaged 1.3 per cent between 2007 and 2022, against 0.9 in 1990-2006, far outpacing other EMs. Partly, the TFP boost has come from efficiency improvements in certain sectors, such as services exports (think ecommerce or consulting). But the biggest improvement is undoubtedly from better basic infrastructure. The country has, for instance, seen a major buildout of seaports, railways, roads and airports, in no small part overseen by the Adani Group. Some fear a concentration of economic power, but Neelkanth Mishra, an economist at Axis Bank and an economic adviser to Modi, argues the average Indian has profoundly benefited:

In 2011, two-thirds of households had electric lines in their houses with five to six hours of electricity. Now, the share is in the 90 per cent range, with 20 hours of electricity on average. [Such a massive improvement] lets you study at night, or cool yourself down, or use induction stoves . . . In 2011, two-thirds of households used firewood [or another organic fuel] to cook! Now most use cooking gas.

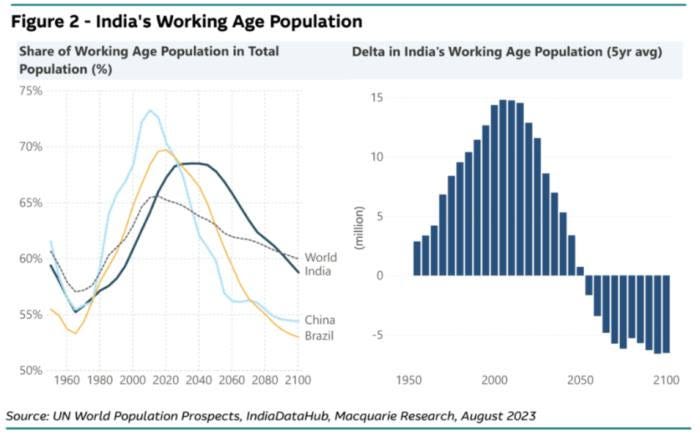

Favourable demography is also lifting India’s economy. On current population estimates, the working-age share of population is expected to rise (and dependency burden fall) for several years. This helps offset India’s dismal female labour force participation and underemployment. Should those improve, growth could accelerate further. And even when the demographic dividend fades, India’s working-age population is poised for a “long plateau” that could last decades, says Suresh, at a time when most other major economies face shrinking, ageing populations:

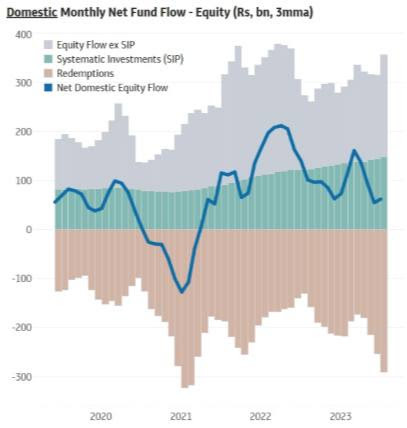

As India’s stock market takes up a growing share of emerging market indices, global investor money has rolled in. But the most enthusiastic buyers of Indian stocks are Indians themselves. One form this takes is retail investors swapping stock tips in WhatsApp groups and driving hyped-up small-cap stocks to ridiculous valuations. But another is the steady rise of systematic investment plans, which put a preset amount of money from your bank account into the stock market. A gradual increase in these schemes has driven domestic equity flows for the past few years (in green, below; chart from Macquarie):

A stable base of domestic equity buyers is good for global investors. Some markets, like China, suffer from flighty retail investors. Others, like Japan, just have too few of them; households are in the aggregate lightly allocated to stocks.

If there is a drawback for India investors, it is that the story has become too popular. The stocks look expensive. At a price/earnings ratio of 23, the Sensex is near the top of its historical range and at a premium to the US, world and EM indices. As Morgan Stanley’s Jitania Kandhari put it to us, rather delicately, Indian stocks are “priced for a very good outcome”. The recent rally in Indian small-cap and lower-quality stocks looks downright irrational. The India story, in short, appears overbought — not a huge worry for long-term investors but clearly worth keeping in mind for those seeking an entry point.

Our question for you, Adam, is whether the Indian geopolitical story is similarly overbought. The global romance with China — or at least the idea of China — seems to be ending in heartbreak. Are the world’s high hopes for India headed for a similar disappointment?

Chartbook: Indian growth is unbalanced and cronyist (Adam)

The transformation of everyday life in India is undeniable and dramatic. Electrification, clean water and decent toilets for hundreds of millions of people are huge achievements. Bharatiya Janata party prime minister Modi is a consummate politician and has skilfully put his personal stamp on a series of developments that were years in the making.

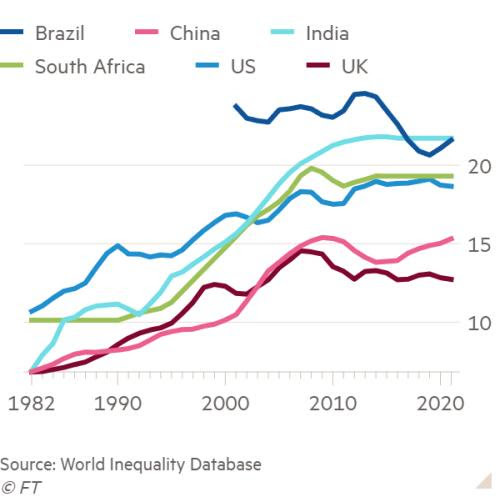

But whilst Modi’s programme sails under the flag of nation building, the benefits of India’s growth have been distributed shockingly unequally. Whereas the share of GDP going to the top 1 per cent grew in China between the 1980s and the 2010s from 7 per cent to 13 per cent, in India it rose from 10 per cent to 22 per cent. India today is more unequal than post-apartheid South Africa and in the same ballpark as Putin’s Russia.

India grew into one of the world's most unequal societies

Yes, there is an Indian upper middle class that invests in the local stock market and that group is growing. But it accounts for 3 per cent of India’s population. By comparison, 13 per cent of Chinese hold some investment in the stock market, as do 55 per cent of Americans. And, as we know from the US, the vast majority of those retail investors have tiny holdings.

By far the biggest beneficiaries of India’s stock market boom are the political insiders who have ridden a well-founded wave of confidence in the strength of their political connections. Best connected of all is Gautam Adani, whose relationship with Modi goes back to the aftermath of the bloody Gujarat riots.

Billionaire families like the Adanis and Ambanis are Modi’s partners in state building. What they are not is globally competitive manufacturing entrepreneurs. In the 1980s India lost out to China as a base for manufacturing globalisation. A generation later, India again failed to capitalise, this time on rising labour costs in China. Bangladesh was far more entrepreneurial and now boasts a higher GDP per capita.

In coming years, it seems that India may benefit from diversification away from China driven by national security concerns. Apple is the most spectacular case. But how far that is going to go remains to be seen. To date it is Apple’s Chinese supply chain experts and engineers who are key to getting the Indian production up and running.

Political connections may not give you the technological edge. But what they do deliver is easy credit. India’s growth has been heavily debt fuelled. Today it is Adani’s financial engineering that makes the headlines. But if you remember back to before the coronavirus pandemic, India was in the grips of a widespread bank crisis. Raghuram Rajan took on the job as governor of the Reserve Bank of India in the hope of cleaning house. By 2016 he was gone.

A jaundiced view of Indian capitalism, such as that offered by Jairus Banaji, sees this merely as the latest iteration of struggles between different business groups and politicians, a cycle that has repeated since the 1930s. In the current moment there is a natural fit between the “promoter” model of capitalism personified by Adani and Modi’s populism.

The more alarmist vision, offered by Ashoka Mody in his powerful analysis India is Broken, is that India today is in the late stages of a failed project of nation building. And the ultimate test of this thesis is not to be found in the stock market, or the inside battles between business groups, but in the human capital endowment of the broad mass of India’s population.

In 2020 on the World Bank’s Human Capital Index — which measures countries’ education and health outcomes on a scale of 0 to 1 — India achieved a score of 0.49, below Nepal and Kenya, both poorer countries. China scored 0.65, putting it on par with Chile and Slovakia, which have higher GDP per capita. Most dramatically disadvantaged are India’s women. Since 1990, Indian women’s labour market participation has fallen from 32 per cent to about 25 per cent. And behind them come hundreds of millions of underskilled youngsters. In 2019 less than half of India’s 10-year-olds could read a simple story, compared with more than 80 per cent of Chinese children and 96 per cent of Americans. In the coming decade, 200mn of these poorly educated young people will reach working age. A large share of them will probably end up eking out a living in the informal sector and getting by on handouts. Unemployment amongst the under-25s already runs at more than 45 per cent.

At the G20, India trumpeted its investments in public sector tech infrastructure. But impressive as they may be, are these handy apps for the delivery of cash and digital services not a way of bypassing the difficult business of building effective government and actually empowering India’s giant population? As Yamini Aiyar argues, despite India’s progress on many metrics, a substantive welfare state remains an illusion.

Indian intellectuals of the subaltern studies school used to lament that India, unlike China, never had a true peasant revolution and the deep social and cultural transformation that might have followed. Today, in the face of the BJP’s onslaught, you hear Indian liberals wondering the same thing. That is the dramatic historical counterfactual implied by seemingly matter-of-fact comparisons with China.

Clearly, in profound ways India’s path is neither that of China, nor that of the west. Looking to the future, what sceptics of Modi’s boosterism ask is whether India might become the forerunner of a rather gloomy new model for populous, lower-income countries, managed, without a powerfully effective governmental apparatus, or globally competitive manufacturing sectors, by digitally enhanced populism, delivering cash payments to the cell phones of hundreds of millions of dependent people. And as the events in Manipur expose, when all else fails, that welfarism can be backed up by mob violence and a dose of harsh repression.

We don’t think of India as a leader in high-tech surveillance, like China. But the flipside of a digitally enabled welfare system is that an internet blackout is a terrifying weapon. And as Human Rights Watch notes, since 2018 the authorities in India have shut down the internet more often than in any other country in the world.

The world right now is a tough place. In need of a counterweight to China, the Biden administration seems determined to embrace India at any price. Investors may feel the same way. It is a big economy, now larger than that of the UK, and a hugely diverse and creative society. No doubt there are ways to make money. But investors should be clear eyed about what they are getting themselves in to.

***

If you have enjoyed the Chartbook/Unhedged exchange and would like to get not only the long-form newsletters, but also the full Top Links mailing (most days of the week), click one of the subscription options below. Thanks for reading!