Chartbook #193 Indian nation-building, Modi and the Adani crisis

The upheaval rocking the Adani business empire is one of the dramatic global developments of the last week.

I was delighted that The Wire saw fit to pick up and republish Chartbook #190. I’ve long harbored a secret ambition to join the ranks of the Wire-wallahs. Cam and I also featured the Adani story on the Pod this week.

With continuing losses on the market, the cancelation of the share sale and moves by foreign investors to clarify the extent of their exposure to Adani, it seems clear that the controversy is not going away as quickly as some predicted or hoped.

The Adani controversy is spectacular. But there is a real danger, if we address it as a question of alleged financial malpractice, that we miss the real issue. This is well brought out by the op-ed by Mihir Sharma:

… talk of cronyism misses the point. If Adani didn’t exist, the Indian government would have had to invent him: The development model we have now chosen requires risk-taking “national champions” such as the Adani Group. … Much of what Hindenburg put in its report doesn’t count as news for Indian investors. They have known for years that Adani Enterprises Ltd., the fulcrum of the Adani empire, is loaded down with debt, and that the ultimate source of its funding is remarkably opaque. Adani stock is generally thinly traded; few here will be willing to believe that Adani companies set out to defraud retail investors, even if both public sector banks and state-owned insurers have bet heavily on them. No, Indians’ real fear is something else — that Gautam Adani and his companies simply cannot do what they say they will. Can they build the roads they have promised, improve the ports they have been given, maintain the airports they won in a bid? Until now, nobody else has been able to do so.

You don’t have to agree with Sharma’s critique of “old-fashioned industrial policy”, to see the force of his point. What is really at stake here is not the purity of financial markets, but a model of economic development. Who, if anyone, can get things done?

On the massive reach of the “Two As” (The Adani and Ambani conglomerates) and their implications for India’s political economy, Arvind Subramian is, as usual, enlightening). Here a talk with The Wire about India’s growth prospects.

For a useful (and rather downbeat) macro-take on the Indian setting of the Adani crisis, I found this thread very helpful.

For deeper historical perspective on India’s growth outlook, you may wish to pick up Ashoka Mody’s typically fiery interpretation of India’s economic development since independence, which is being released by Stanford University Press this month.

Trigger warning: Mody’s treatment is a no bolds barred attack on “India boosterism”:

Challenging prevailing narratives, Mody contends that successive post-independence leaders, starting with its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, failed to confront India's true economic problems, seeking easy solutions instead. As a popular frustration grew, and corruption in politics became pervasive, India's economic growth relied increasingly on unregulated finance and environmentally destructive construction. The rise of a violent Hindutva has buried all prior norms in civic life and public accountability.

It is particularly striking for its moral tone.

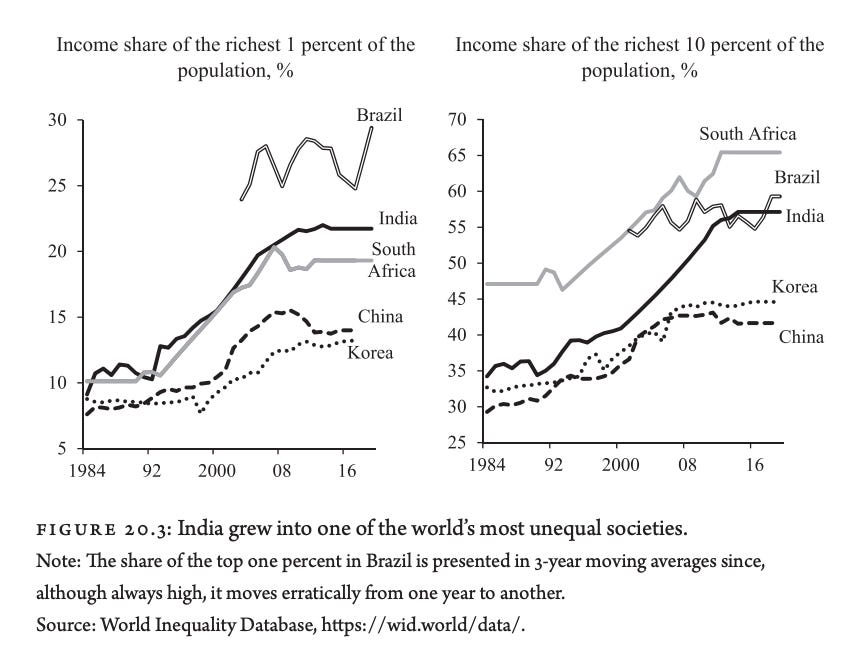

Mody does not deny the growth, which in recent decades has lifted hundreds of millions out of absolute poverty. But he also highlights mounting inequality, which now places India alongside South Africa and Brazil as one of the most unequal societies on earth;

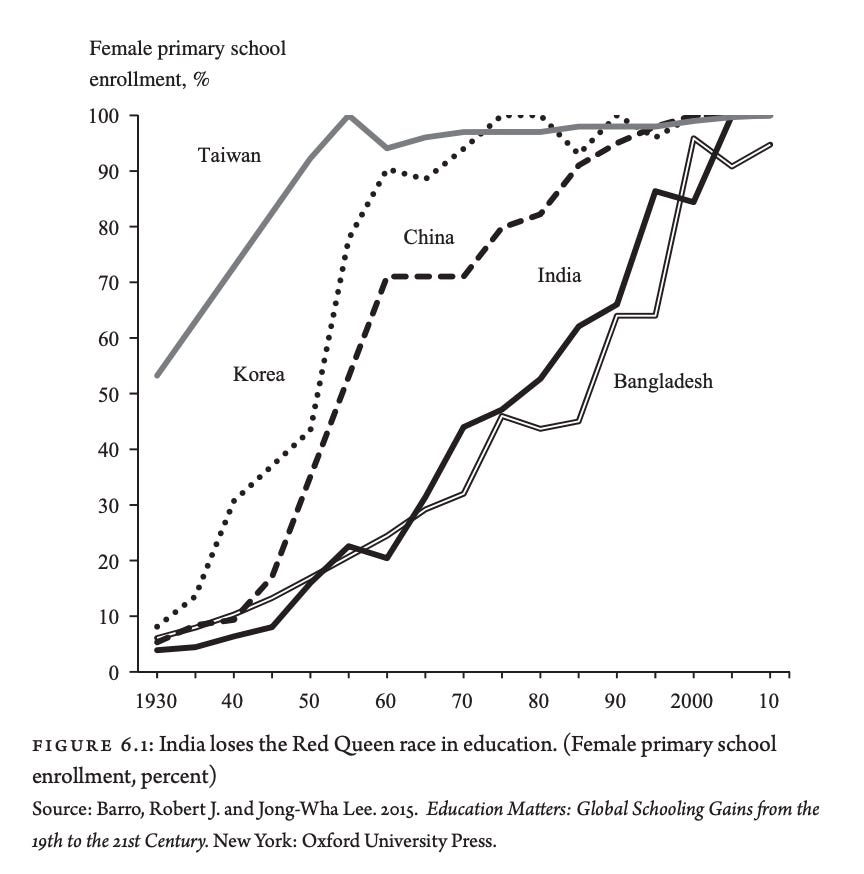

India’s failure to keep up with its Asian rivals above all in female education;

And the chronic problems of unemployment and underemployment that result from failing to find a suitably-sized niche in the global division of labour.

Compiling a list of critical voices like this, you can easily come across as though you don’t appreciate the dramatic transformation in material circumstances which India and Indians have achieved since the 1980s. In fact, a critical perspective on contemporary India and its politics acquires even more force if you reckon with the reality of spectacular change.

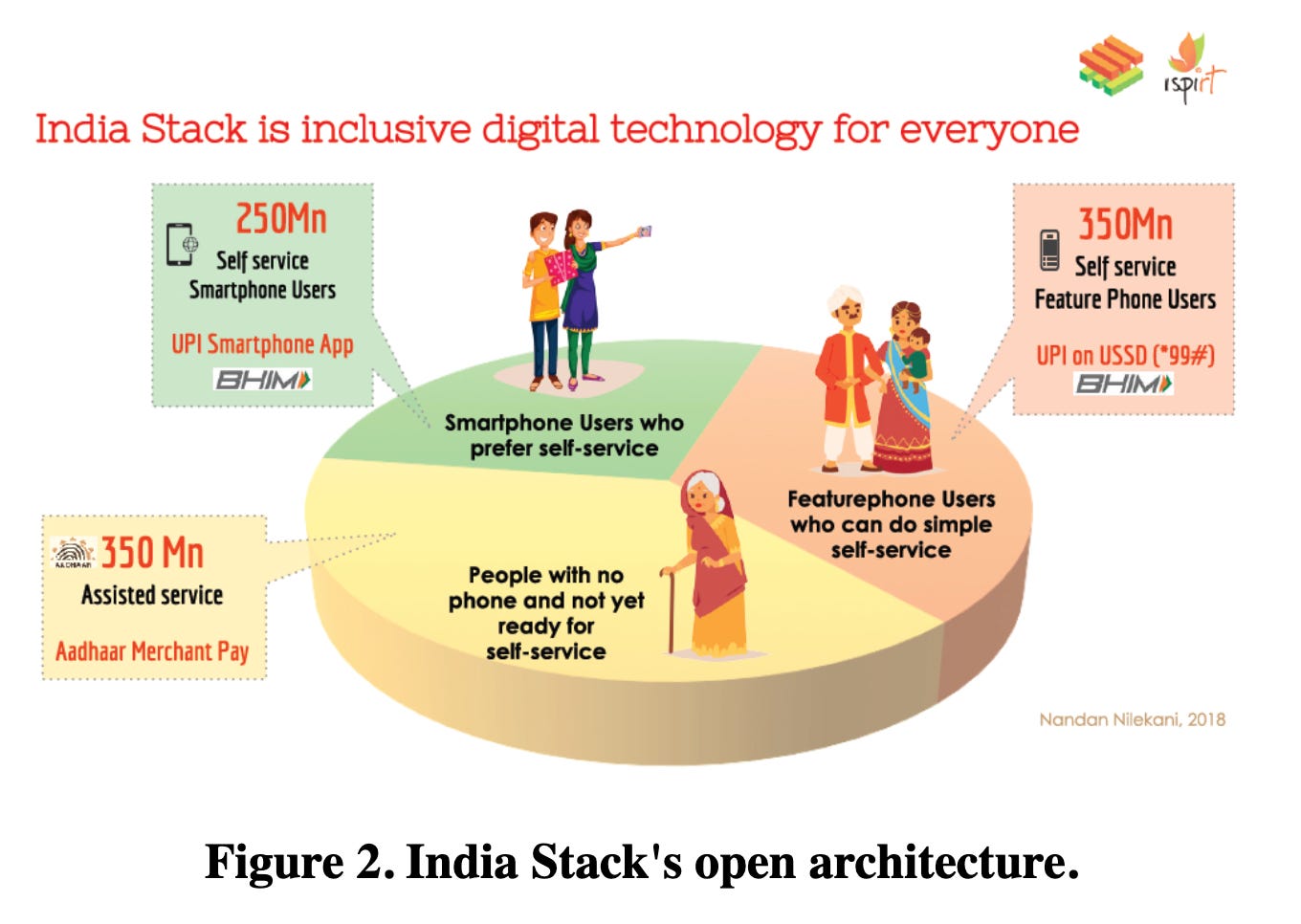

Take the remarkable digital infrastructure known as the “India Stack”, starting with the campaign for complete biometric identification set in train in 2009.

For an uninhibited celebration of digital infrastructure as a mechanism for incorporating hundreds of millions of people, both into the governmental machinery of the Indian state and a national market, see Raghavan et al 2019. The graphic below rather nicely illustrates the way in which technology maps onto a caricatured sociology of 21st-century India. A society split three ways between (1) fully empowered smart phone users, (2) families in more traditional clothing accessing services on simpler cell phones and (3) elderly village dwellers whose access is enabled indirectly by way of Aadhar-tied merchant pay terminals in every village across India.

For a more critical take, locating the Aadhaar system in the history of the Indian state, check out this piece by Kavita Dattani also from 2019. The abstract does a good job of explaining what is at stake.

In many of the ex-colonies of European empires, biometric technology systems are being built under an ethos of welfare and financial service delivery. One case in this broader trend of postcolonial governance is India's Aadhaar and India Stack. This paper uses this case to explore how the in-sourcing of technology into means of governing, behind a front of participatory “good governance,” is contributing to the historical trajectory of citizenship regimes in India. Through claims of reducing financial “leakages,” Aadhaar, a biometric identification database consisting of fingerprint, iris scan, and photograph, has become compulsory for accessing welfare in India. The Indian government makes a case for Aadhaar using a propaganda discourse of its success, based on weak evidence. The India Stack, a set of cloud-based application programming interfaces (APIs) built on top of the Aadhaar database, offers a digital infrastructure for private companies to verify identities using Aadhaar data and to offer other “services” including “financial services.” The ability to access data, paired with a “revolving door” of individuals between state and corporations, points to an ulterior goal of both Aadhaar and the India Stack: creating winners in the corporate and financial technology sectors. The Indian corporate-state run through a “governtrepreneurism” uses Aadhaar and the India Stack as new digital technologies of governmentality to transform populations into subjects or customers.

To anyone who has to deal regularly with the antiquated pre-digital processes of governance in either the United States or many parts of Europe, the degree of digitization in India often beggars belief.

New Delhi in its role as G20 president is now putting India’s digital stack in the global spotlight. Delhi is selling “India Stack Global” as a model for tech and governance solutions worldwide, but particularly for middle- and low-income countries.

Digitization would be completely unthinkable, if it were not for the progress that has been made in the electrification of India.

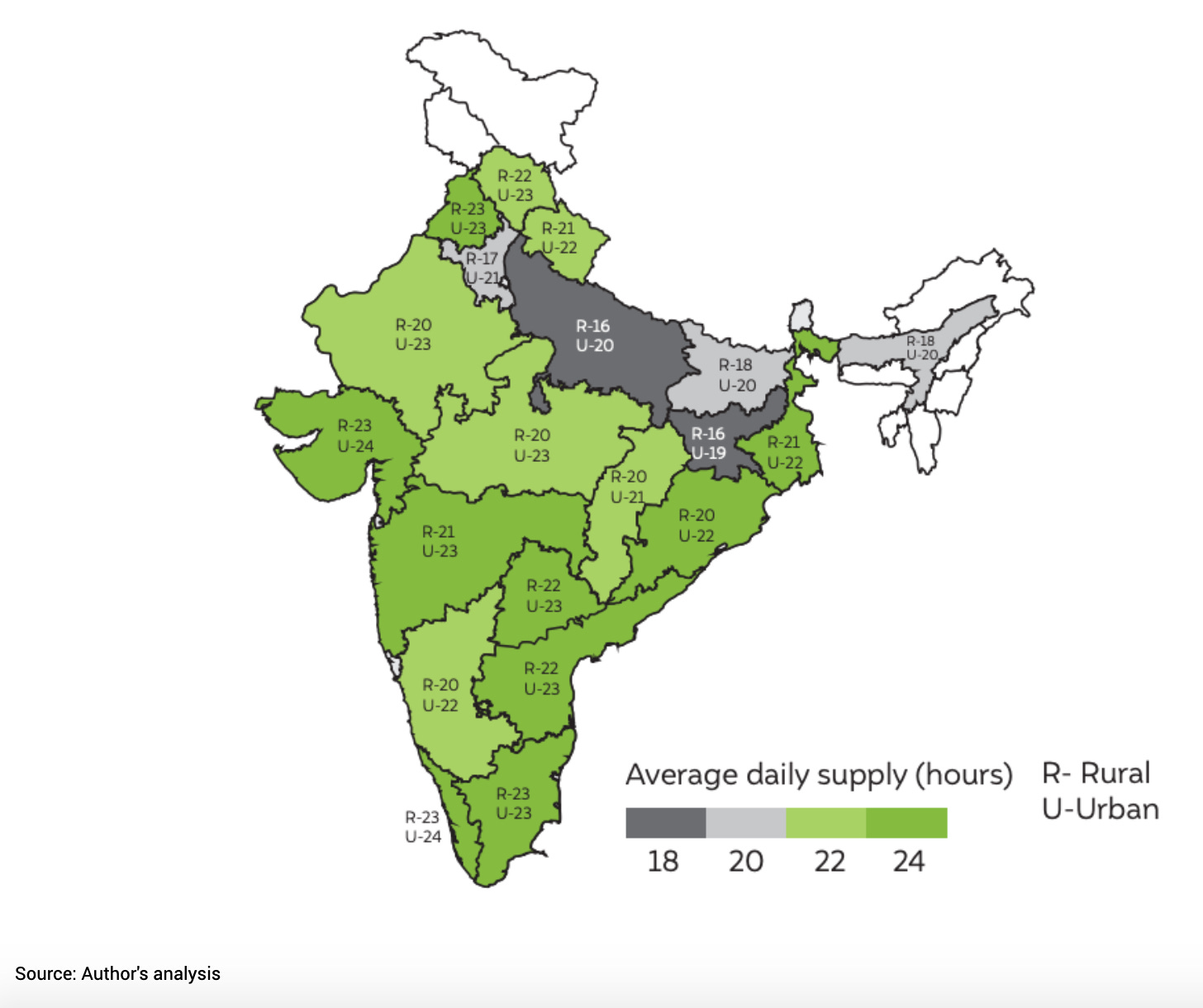

These data are from the India Residential Energy Survey as analyzed by Shalu Agrawal et al of CEEW.

Of course, India’s per capita power consumption is still very low compared to China or advanced economies. Nor does connection to the grid mean 24-hour power supply. Especially in the rural North-East, power supply is intermittent. But, a generation ago, less than half of rural households in India had any connection to the power network at all. Now almost 97 percent do.

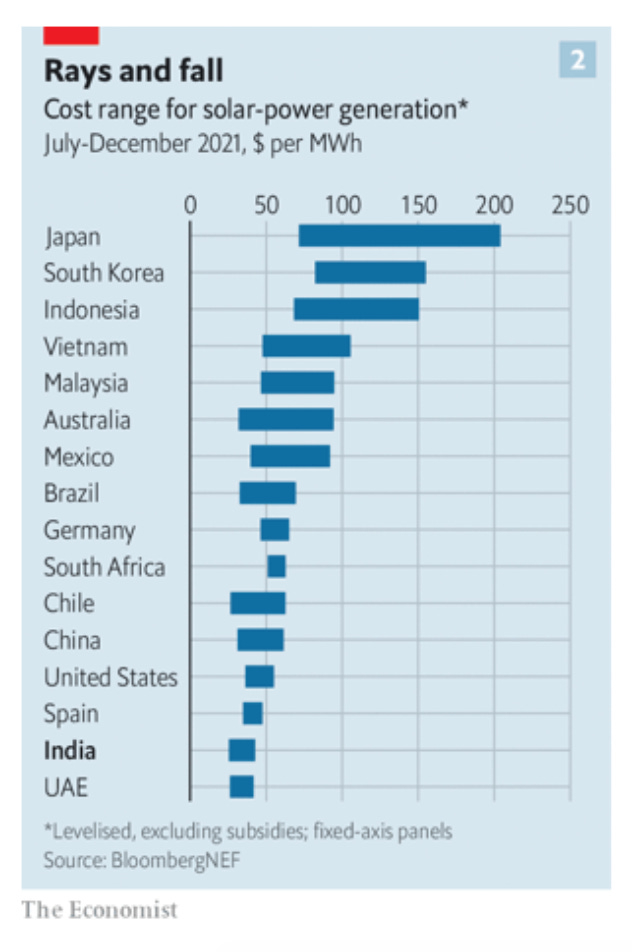

Historically, India’s energy system has been heavily dependent on coal. Gautam Adani is a coal baron notorious for his giant Australian development plans. But since PM Modi has committed India to decarbonization by 2070, Adani has also become a champion of India’s energy future as a renewable energy power house with some of the lowest per unit costs of both solar and wind in the world.

Source: Economist

Both the Ambani and Adani groups have seized on the new agenda, promising to make India a hydrogen champion and “indigenising the entire supply chain”. No longer will the value of India’s currency fluctuate with the oil price even as it did in the last 12 months.

It adds up to an impressive and coherence vision of change. Comprehensive digitization, fed by an encompassing national grid, powered by national renewable energy generation - this is nation-building for real. And it matters all the more in a society in which, as Elizabeth Chatterjee has shown us, electricity has long been seen as an integral part of the national welfare state and the project of nation-building.

However ambiguous this progress and however complex are its explanations - it clearly began decades ago - it has foundational significance for contemporary India. You cannot understand the genuine mass appeal of Prime Minister Modi and the BJP unless you recognize the way in which they have managed to associate themselves with a real and very dramatic transformation and at the same time to cast their opponents as those who for so many decades failed to deliver even the most basic services for India’s population. Following the Gujarat model of privatized infrastructure model, corporate interests are not shamefaced but front and center in this vision of nation-building. Nation-building is the key boast of the Adani group. And it is that model that is at stake in this crisis.