In the urgency of the present, our thinking about Ukraine is drawn to the immediate past. We place the current crisis against the backdrop of the “Maidan revolution” of 2013-2014, or the first escalation of tension with Russia in 2007-2008, or the orange revolution of 2004. We go back to the fateful negotiations between 1991 and 1994 over the end of the Soviet Union and Ukraine’s nuclear weapons between.

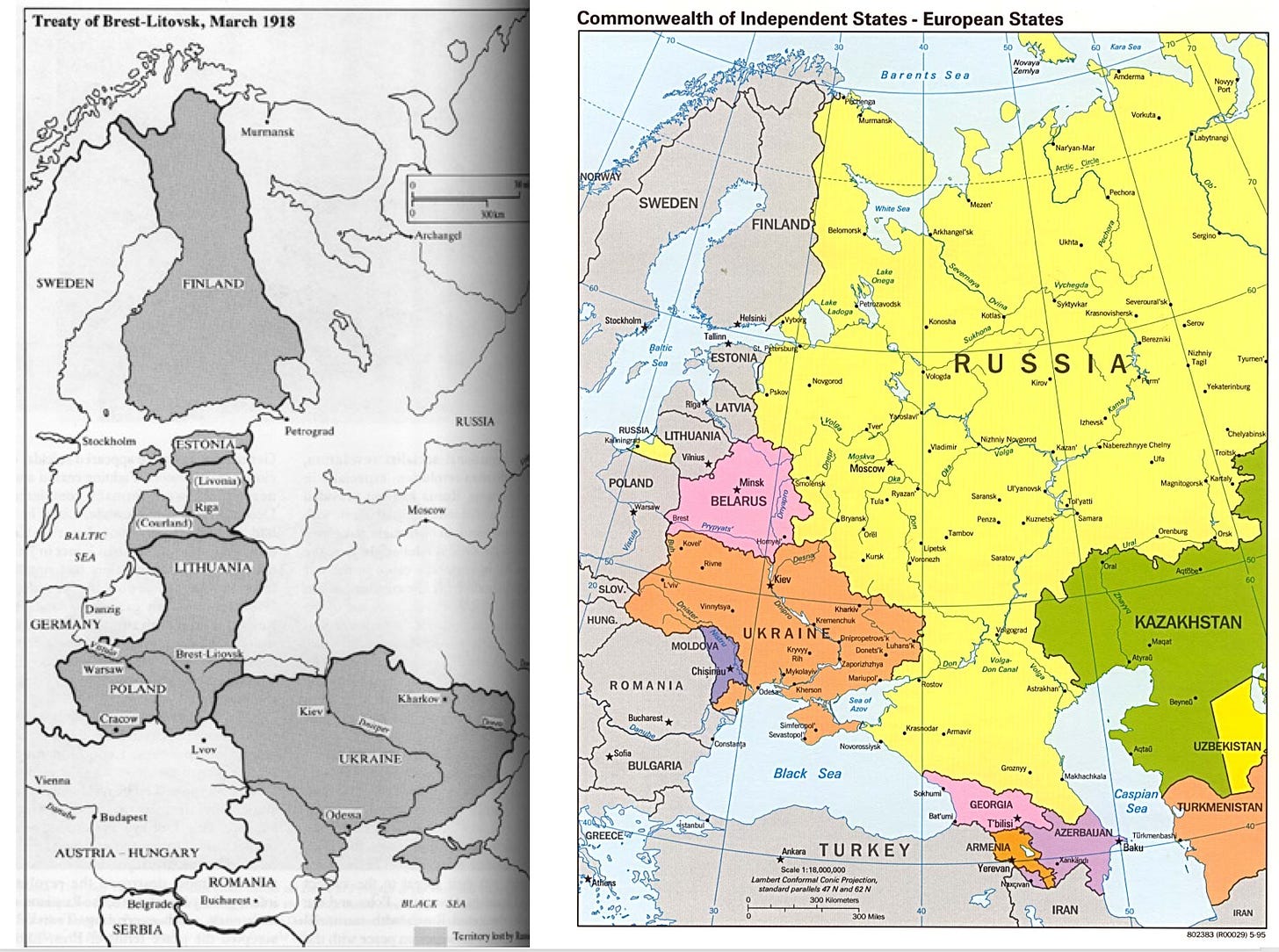

But the history of the Ukrainian nation state in its modern form is older than that. The first Ukrainian nation state to achieve international recognition emerged out of the first great crisis of the Russian empire in 1917-1918. It was solemnified by the Treaty concluded on 9-10 February 1918 by a youthful group of representatives of the Ukrainian parliament, the Rada (which had constituted itself in the course of the 1917 revolution), and the central powers - Imperial Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.

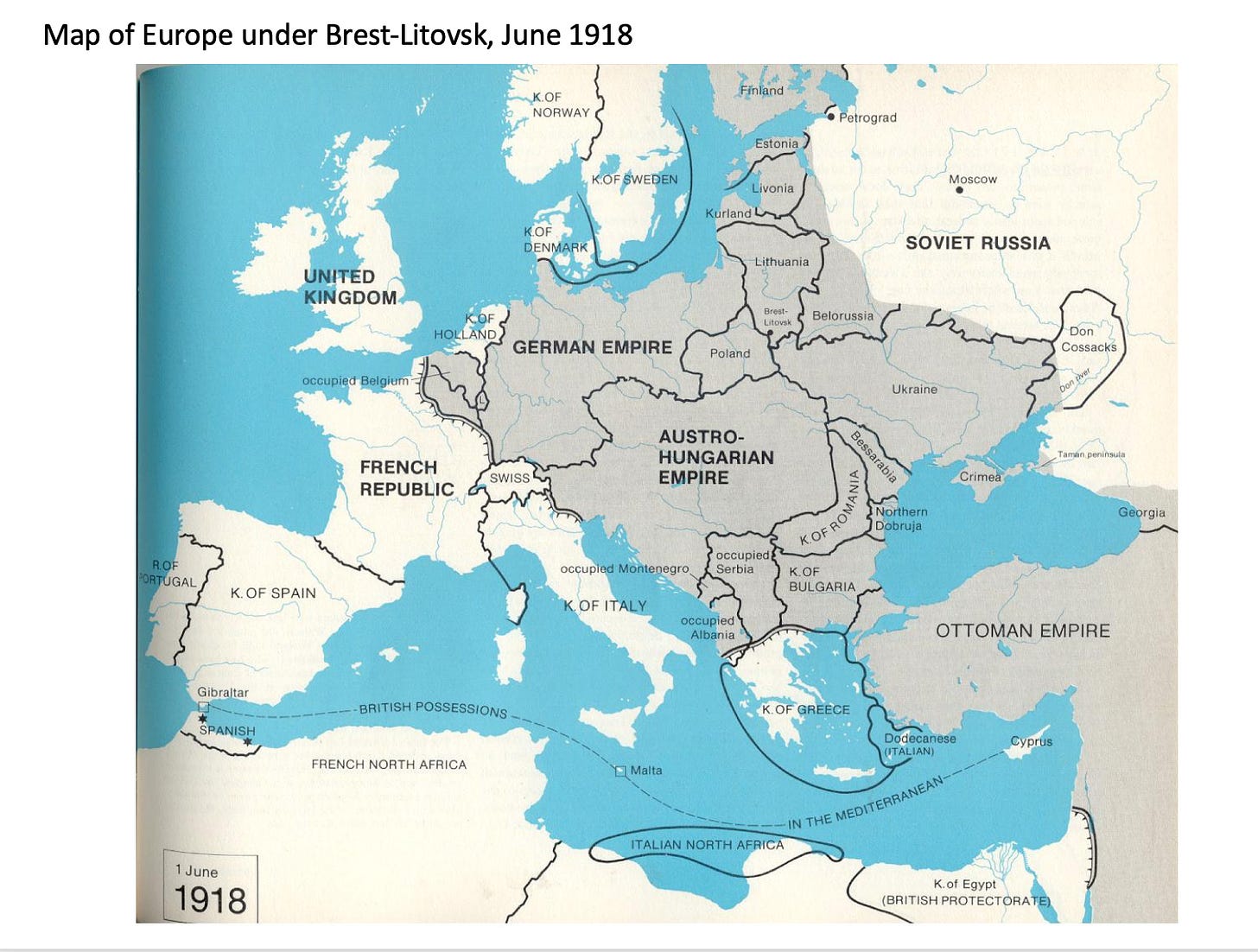

It was the first Treaty to be concluded at Brest-Litvosk, where in March the Bolsheviks and the Central Powers would sign their notorious peace. If you are looking for a historical precursor to the post-Soviet map of Europe this is it.

This is what Putin means when he refers to 1991 as a geopolitical disaster.

For a short account of this moment from the perspective of Ukrainian national history see this essay in the FT by Serhii Plokhy.

For a fascinating historical account of Brest-Litovsk John Wheeler-Bennett’s The Forgotten Peace, Brest-Litovsk, March 1918 is still irreplaceable. Published in 1939, Wheeler-Bennett even managed to interview Trotsky in Mexico.

Another rich account is to be found in Fritz Fischer’s Griff nach der Weltmacht (aka in English as Germany’s Aims in the First World War). Fischer’s book is famous for its interpretation of the July crisis of 1914. But it is, in fact, a far wider account of Germany’s grand strategy in the entire war and excellent on Brest-Litovsk.

I discussed Brest-Litovsk and the German sponsorship of an independent Ukrainian state, in key chapters in my book Deluge. It serves for me to subvert the Wilson v. Lenin framing of the aftermath of World War I.

On the Brest peace treaty in comparison with Versailles I gave this lecture at Stanford, in 2014, in the immediate aftermath of the Maidan revolution.

More briefly I place the Brest negotiations in the context of the German war effort in the “War in Germany” lecture series. You can view a zoom version of the lecture, slide show and some Q&A with students here.

Also useful as an introduction to the peace talks from the Soviet point of view is this atmospheric account by David Stone.

For our current purposes, the really important point to make is that Germany was serious in backing the creation of a Ukrainian state.

Some of Germany’s strategists viewed this in terms of a calculus of Realpolitik pure and simple. What better tool than the doctrine of self-determination with which to explode the Tsarist Empire? Splitting off the Baltics, Poland, Belorusse, Ukraine the Caucasus states would reduce Russia to a rump.

But to view German sponsorship of Ukrainian independence simply as a matter of creating a “satellite state”, is reductive.

Germany’s own constitution was in flux. As the war dragged on, the majority coalition of Social Democrats, liberals and Christian Democrats that had won the elections to the Reichstag in 1912, was pushing ever more to the fore. In this way Germany was no different than any of the other combatants, total war changed the political regime.

The Reichstag majority shaped the peace-making at Brest in a double sense.

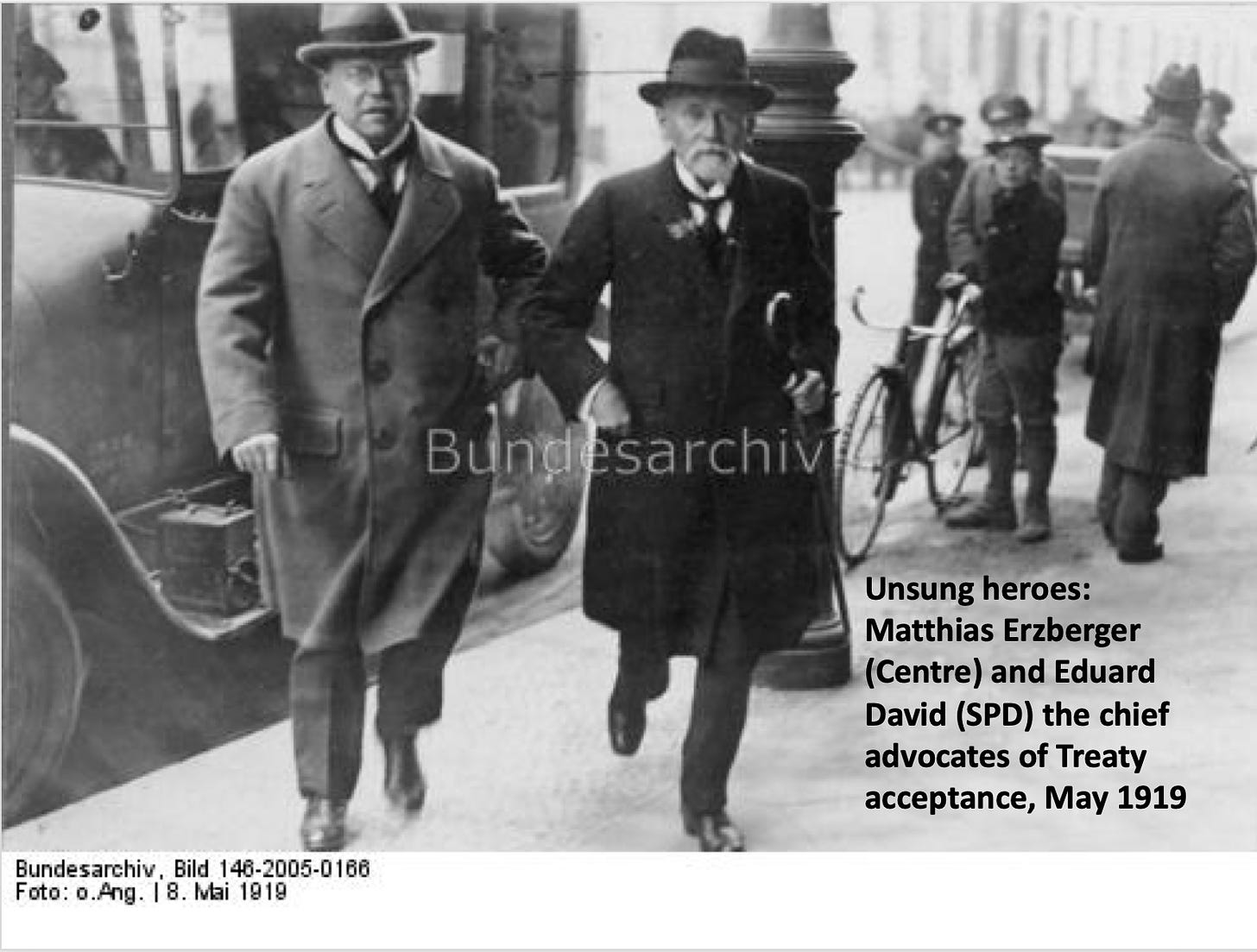

The Reichstag majority led by Matthias Erzeberger of the Catholic Center Party and the Majority SPD viewed the manner of peace-making in the East and specifically in Ukraine as a test for who would hold power in a German empire after a victorious peace. Would it be civilian politicians and diplomats, or would it be the military?

The eventual German military coup in Ukraine was denounced as illegal in fierce debates in the Reichstag. The military’s disastrously high-handed actions contributed to the fundamental rupture in relations between the Reichstag majority and the German government, which set the stage for the upheaval of the autumn and the eventual revolution.

But it was not just issues of domestic political order that were at stake. Erzberger and Eduard David articulated not only a domestic vision, but a distinctive centerist vision of German international power. They wanted to see a dramatically reformed Imperial Germany not only as a dominant military and economic force, but as a hegemon of a restructured East Europe in a broader sense. In structural terms they are precursors of German policy since 1991. In conception, their vision was, if anything far more expansive than that of Kohl, Schroeder and Merkel.

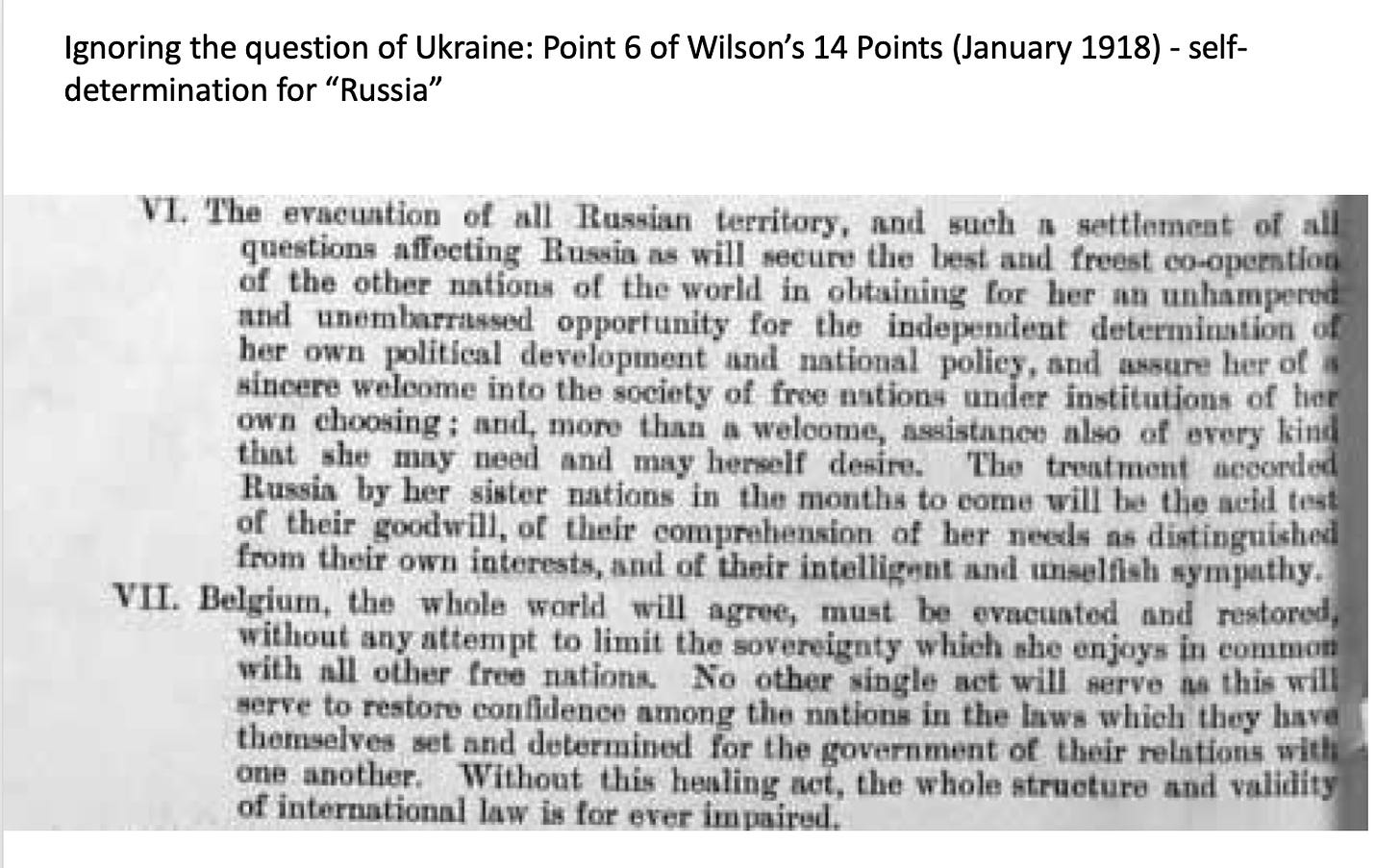

The key point is that like the Entente and Woodrow Wilson, the Reichstag majority in Germany were arguing over how to end World War I with a “progressive” modern peace. They were motivated not just by ethical and political commitment, but also out of realism. In their view only a peace based on some version of self-determination could form the basis for a stable long-term order. But, unlike Woodrow Wilson, the Germans understood the significance of the “Ukraine question”.

In his famous 14 points manifesto issued in January 1918, Wilson simply ignored Ukraine. Point 6 blithely dismissed the question of the autonomy of peoples within what had been the Tsarist Empire.

The US strategy was calculated. Wilson was still holding open the door to cooperation with the Bolsheviks. German strategy too was divided over the question of the integrity of the Russian state.

Some conservative military men aimed for the restoration of a pro-German conservative regime in Moscow. Others sought a modus vivendi with the Bolsheviks, which as far as Germany was concerned had the added advantage that the Bolshevikss seemed like a guarantee of chaos and internal dissent, neutralizing Russia as a power factor. The most constructive option favored by the likes of David, Ebert and Erzberger was German sponsorship of a chain of successor states, including Ukraine and Georgia. Nothing else, in their view, promised long-term power. Nothing else promised lasting hegemony.

Furthermore, the issue of peace-making at Brest-Litovsk was not confined to diplomacy and high politics. The negotiations, which, unlike those at Versailles, were actual negotiations with all parties present, were widely reported in the German and Austrian press. Over the winter of 1917-8 the popular parties both in Austria and Germany were channelling a massive democratic force that urgently demanded an end to the war.

The Social Democratic majority had agreed to back the war in 1914 not just out or generic patriotism but specifically with a view to defending Germany against the threat of invasion from the East, by the armies of the Tsar.

With victory in the East achieved, there was little desire to continue the war. Strikes broke out already in April 1917 following the February revolution in Russia and there was a further wave of mobilization both in Germany and Austria over the winter of 1917-8.

The workers protests of the winter of 1917-8 were political demonstrations, but they also made concrete material demands. It was not just peace that the German and Austrian workers demanded, but bread. The home front was slowly starving, in Austria acutely so. A peace with Russia and Ukraine promised bread. What the population wanted was a Brotfrieden.

Given this pressure, the Austrian delegation to Brest-Litovsk were so desperate for a peace and a trade deal with Ukraine that they were even willing to make territorial concession to the Ukrainian negotiators.

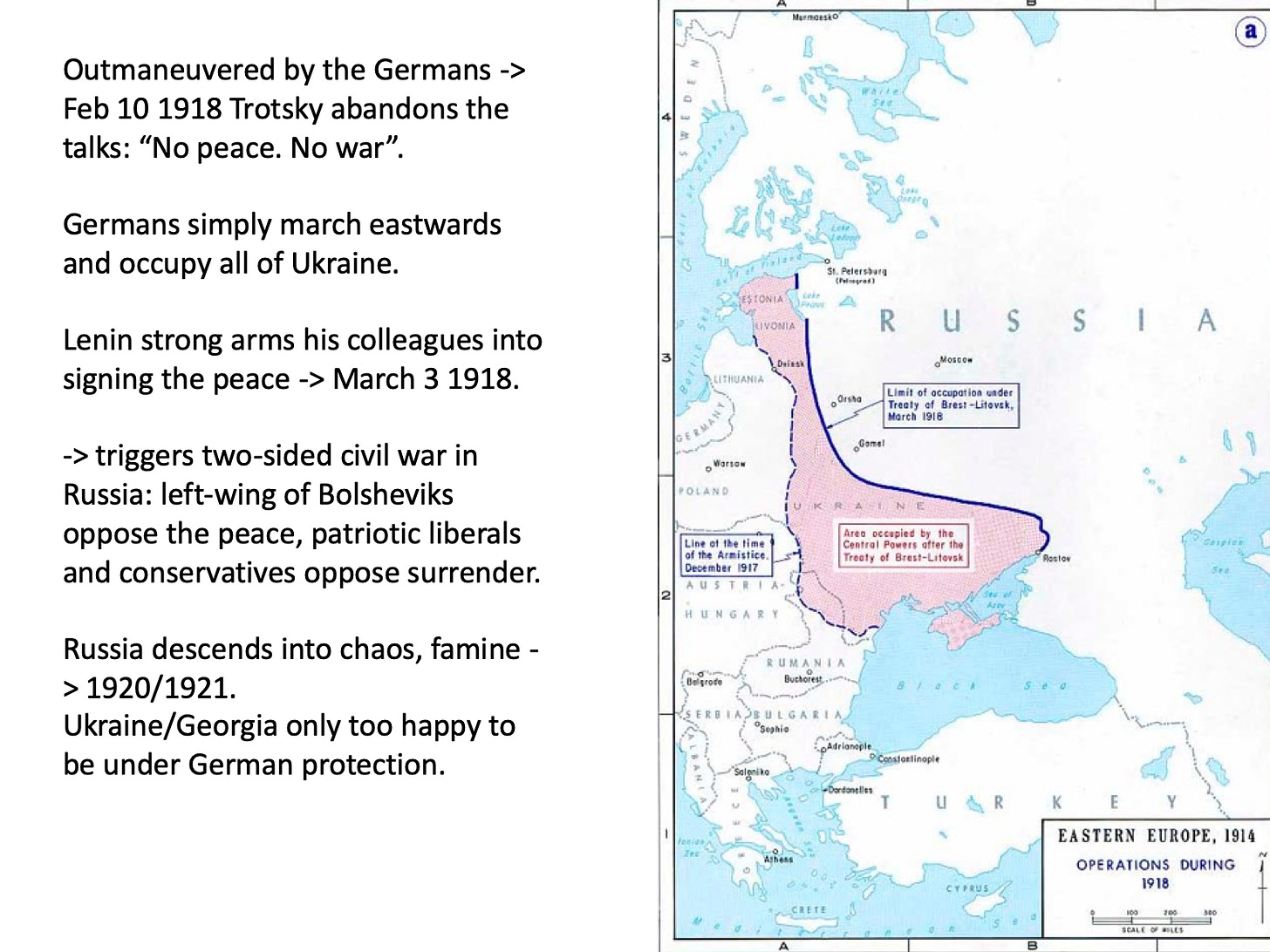

Though these strategic interests were clear, the pace of the negotiations with the Ukrainians and the conclusion of a peace already on 9 February was a means of exercising leverage over the Bolshevik delegation. And it worked, triggering Trotsky’s famous “No peace. No war” demarche.

As the Bolsheviks withdrew from the talks, this opened the door to the rapid advance of German forces into Ukrainian territory and beyond.

It was only when they faced military catastrophe that Lenin managed to assert his pragmatic line and the Bolsheviks came to terms.

Meanwhile in Ukraine the modus vivendi between the Rada and the German military forces on the spot rapidly unraveled.

As I tell the story in Deluge:

In 1918 Austria and Germany confidently expected at least 1 million tons from their new Ukrainian ally. But by the end of April it had become clear that ‘exploiting’ the bread basket of the Ukraine would present more problems than these fantasies allowed. If they were to avoid the enormous costs of a full- scale occupation, Austria and Germany needed a cooperative local authority to collaborate with them. Having been driven out of Kiev (by a Bolshevik attack), only to be restored courtesy of the German Army, the Rada needed a breathing space to re- establish itself. But the scale and urgency of Germany and Austria’s economic demands made this impossible.

In Ukraine, as in the rest of revolutionary Russia, the only way to secure popular legitimacy was to cede possession of the land to the peasants. Over the summer of 1917 a nationwide land grab had redistributed the gentry’s estates. In the nationwide Constituent Assembly election, the peasants of Ukraine had voted in their millions for the party that promised a village- based agrarian future, the Social Revolutionaries. The SRs were reliable allies against the Bolsheviks, but their land policy ran directly counter to the interests of the Central Powers. To maximize the surplus available for export, they needed cultivation to be concentrated in large, market- orientated farms. For the Rada to have presided over the restoration of the great estates for the sake of its German protectors would have discredited it completely. For the Germans themselves to reverse the agrarian revolution by force would have required hundreds of thousands of troops from the Western Front that Ludendorff could ill afford.

If the Germans had been able to barter desirable manufactured goods in exchange for grain deliveries, this conflict might have been alleviated. Under the Brest- Litovsk Treaty, Germany had committed itself to trading grain for industrial goods. But under the strain of the war effort, goods for export were in desperately short supply. To purchase the grain they needed, the Central Powers resorted to the short- term expedient of simply ordering the Ukrainian National Bank to print whatever currency they required. This gave them purchasing power and avoided requisitioning, but within a matter of months it rendered the currency worthless. As General Hoffmann noted from Kiev: ‘Everyone is rolling in money. Roubles are printed and almost given away . . . the peasants have enough stocks of corn to live on for two or three years, but they will not sell it.’

Having reached this point, there was no alternative but to resort to coercion. In early April, Field Marshal Hermann von Eichhorn, the German occupation commander, issued a decree requiring compulsory cultivation of all land. However, the Field Marshal acted without the approval of the Rada and the deputies refused to ratify the decree. Within days, the German military decided against diplomacy. In a coup d’état they ousted the Ukrainian National Assembly and installed a so- called Hetmanate under the Tsarist cavalry offi cer Pyotr Skoropadskyi. 37 Only six weeks after the ratification of the Brest- Litovsk Treaty by Germany’s own Reichstag, under the pressure of economic necessity, the German military had unilaterally abandoned any residual claim to be acting as the protector of the legitimate cause of self- determination. Skoropadskyi spoke virtually no Ukrainian and filled his cabinet with conservative Russian nationalists. The real power- holders in Germany seemed to have lost interest in the project of creating a viable Ukrainian nation state. Instead, they appeared to be readying Kiev as the launching pad for a conservative reconquest of all of Russia.

The result, as Erzberger lamented in the Reichstag was not just discreditable, but dysfunctional. ‘A German soldier can no longer show himself unarmed in Kiev. . . . . . the railway men and workmen are planning a general strike . . . the peasants would not deliver any grain, and bloodshed must be reckoned with in the event of requisitioning’. Instead of the 1 million tons promised under the peace treaty, the Ukraine delivered no more than 173,000 tons to the Central Powers in 1918. 54 But it was not bread alone that was at stake. The question that concerned Erzberger and his colleagues in the Reichstag majority was who controlled the Reich. 55 In future Erzberger demanded all measures in the Baltics and Ukraine should have the approval of the Reichstag.

By June, Ludendorff’s staff had lost any interest in long-term sponsorship of an independent Ukrainian state. Instead, they hoped to march to Petrograd and install a pro-German conservative government for all of Russia that would trade the return of Ukrainian to Russian sovereignty in exchange for German economic domination of all of Russia.

As Germany’s position on the Western front collapsed, the Reichstag found itself struggling to prevent the generals from launching a final German offensive in the East towards Petrograd. As they were agonizingly aware they were, de facto, helping to assure the survival of the increasingly terroristic Bolsheviks regime, which they abhorred on political grounds.

And, as Germany’s power collapsed, so too did the regime it had created in Kiev. Skoropadsky’s regime did not last beyond December 1918 when Ukraine became a People’s Republic.

***

What do I take from this episode for an understanding of the present?

Ukraine has long been one of the fulcrum’s of Eurasian history.

Its history is distinct from but willy-nilly tied to that of Russia.

It history is shaped by the violent play of forces between Russia, Europe (Germany) and wider global empires (British Empire, US).

That play of forces can be crushing, but it can also, in surprising ways, empower Ukrainian actors, who have repeatedly shown their capacity to exploit historic opportunities.

Any far-sighted and realistic vision of order in Europe, including Eastern Europe must reckon with the force of self-determination.

Sovereignty has an economic foundation.

Simple coercive extraction is extremely expensive and not likely to be a good strategy of power.

****

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

Giving a shoutout to the Revolutions podcast, which now in its tenth season is taking on the Russian Revolution in all its depth -- and a listen there corroborates what you say here, Ukraine is its own actor but enmeshed (as we all are) in Russian and European history. http://www.astro.wisc.edu/~jwp/revolutions-episode-index.html

Do you think Biden and NATO are willing to force Zelensky and the Rada to concede to the loss of the East and Southern Coastal areas, and Crimea, to prevent what they widely fear - a confrontation with Russia in the air first, then on the ground? Isn't that what the NYET on a NO Fly Zone means? Will the news coverage on CNN outflank this peace at Ukrainian's cost strategy? By that it a race between Russian atrocity and Western reluctance to take risks... If Putin observed Biden's negotiations with Joe Manchin, what does he fear...