Chartbook #51: Explaining the energy dilemma of 2021- the 2014 shock and the global energy business.

... an answer to Cédric Durand.

In 2021 energy prices around the world surged triggering talk of an “energy crisis”.

Why did the supply of coal, oil and gas fall so far short of demand? After an article in the New Statesman and exchange with Richard Seymour I return to the question again not only because the energy industry is complicated and fascinating, but because the answer we give is crucial to locating where we stand in the battle for the energy transition.

The canard that continues to circulate is that the supply shortfall is directly connected to climate policy. Too much talk about net zero has discouraged fossil fuel investors, resulting in lower investment, restricted supply and vulnerability to demand shocks. This idea has an obvious attraction for fossil-fuel lobbyists, who can use it to argue that the energy transition should be postponed. But it also has traction on the left, as argued most recently and explicitly in Cédric Durand in an essay entitled “energy dilemma” on the New Left Review blog. In New Left Review he writes:

“capitalism has already experienced the first major economic shock related to the transition beyond carbon. The surge in energy prices is due to several factors, including a disorderly rebound from the pandemic, poorly designed energy markets in the UK and EU which exacerbate price volatility, and Russia’s willingness to secure its long-term energy incomes. However, at a more structural level, the impact of first efforts made to restrict the use of fossil fuels cannot be overlooked. Due to government limits on coal burning, plus shareholders’ growing reluctance to commit to projects that could be largely obsolete in thirty years, investment in fossil fuel has been falling. Although this contraction of the supply is not enough to save the climate, it is still proving too much for capitalist growth.”

The attraction of this kind of argument for a crisis-theorist of a Marxist bent is obvious. It has about it the ring of a contradiction from which one could then derive a general crisis model. It has also had a surprising amount of currency in the pages of the FT. It is, after all, a plausible-seeming scenario. But, as an account of the 2021 energy crisis it is fundamentally misleading. It attributes far too much influence to climate policy and mistakes the basic dynamics of investment in the sector.

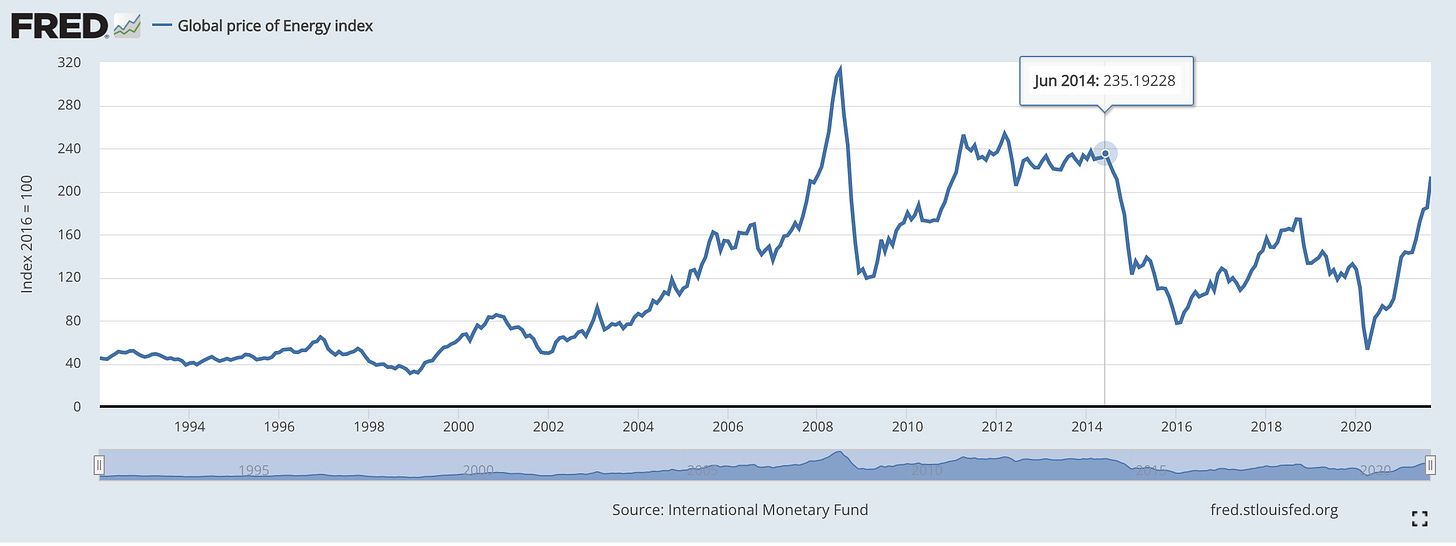

Rather than the political trajectory of climate policy, the starting point for an analysis of developments in the energy sector in recent years should be the energy market price shock of the summer of 2014, when, between the summer of 2014 and 2016, an aggregate index of energy prices fell by two thirds.

Source: FRED

It is this collapse of global energy prices that has dictated both the patterns of investment in the global energy industry, and the balance between fuel types in electricity generation, not only in EU but in the US. Both of these developments have framed the new era of ambition in climate policy, but the causation originates in the energy price shock.

After the 2015 Paris accords, the ramping up of climate ambition did coincide with a slump in gas and oil investment. But, it was not the former that caused the latter. A decline in fossil fuel investment attributable to an increasingly credible commitment to net zero, would likely take place in a gradual way. After 2014 investment plunged.

Source: IEA 2019

The huge shock to energy prices also led to an adjustment in the pattern of energy use. If gas could be bought at rock bottom prices, thanks in part due to the abundance created by the American shale revolution, then flexible gas-fired power plants could replace coal-fired electricity generation. After 2014 the “dash for gas” was key to driving coal out of the power-chain. Even with Trump in the White House the effect continued to operate. Coal was simply uncompetitive relative to gas. Thus, coal dies in Europe and the US in the years after the Paris conference of 2015. But the causal effect runs through the energy market. Both in the US and the EU, climate policy was not just a secondary factor. It was politically enabled by the historic depression in energy prices.

The fossil fuel sector did not so much retreat after 2014 as regroup. The collapse in investment after 2014 was sudden and severe. But, even off their peak levels, investment in fossil fuels continued on a par with the level in 2007-8, just prior to the financial crisis. And costs were lower, so you got more bang for your buck. In the US, the Obama administration, threw its weight foresquare behind America’s new, shale-based oil and gas industry. Literally days after signing the Paris climate accord in 2015, Obama signed off on Congressional legislation authorizing American oil exports for the first time since 1975. For the Obama administration there was no energy dilemma. Pushing climate policy in the Paris-mode was fully compatible with continuing to invest in America’s future as a fossil-fuel superpower. Only blind climate denying GOP ideologues and hired hands of the coal industry would mistake the Obama administration as having been hostile to fossil fuels. For America’s allies, American gas was made of “freedom molecules”, displacing oil and gas sourced from authoritarian regimes. Conventional international carbon accounting does nothing to constrain this logic. Fossil fuel exports are not counted towards national carbon targets. Hence, Saudi Arabia can promise to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, by powering its own economy with solar, whilst continuing to invest on a massive scale in Saudi Aramco’s export capacity.

Certainly, the cutback in the rate of new investments suffered by the oil industry after 2014 was not enough to induce any shortage of capacity. In the second and third quarters of 2021, when the surge in oil prices began, America’s EIA estimated that OPEC had the capacity to pump at least 7-8 m extra barrels per day, compared to global demand of c. 100 m barrels per day.

If Saudi Arabia and Russia have recently had problems in surging production, as analysts like Josh Young of Bison Investments observe, it is to do with “logistical hurdles, political turbulence and U.S. sanctions”. Likewise, if there is a force holding back new investment in America’s shale industry today, it is not government climate policy, but the insistence by Wall Street that the shale industry actually pay out dividends rather than plowing back its earnings into new drilling.

You might think that the arrival of electric vehicles would weigh in the balance, darkening the horizon for the oil producers. But Exxon and co imagine a future for themselves as suppliers of feedstock to the global chemicals industry. And as far as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf producers are concerned, given their ultra-low cost base, they know that they will be the global suppliers of last resort. They may, in fact, have an interest in investing in new capacity so as to be able to conduct a fully fledged price war with a view to knocking out their higher-cost competitors.

As far as oil is concerned, in 2021 the energy dilemma is a non-factor. The current surge in oil prices is the result of a deliberate policy decision by OPEC and Russia to throttle production and allow prices to rise. The producers want to take profits to restore their cash balances and reward their investors for their patience since the shock of 2014.

Likewise, though overall gas investment was off its peaks after 2014/5, one can hardly speak of an investment strike in the gas sector. The outlook across the industry globally was buoyant. Worldwide, gas has consolidated its share of electricity generation at c. 23 percent. Given global growth that created considerable need for new investment. Interest was particularly strong in the LNG field - the part of the global gas supply that is traded by long-range carrier rather than by pipeline. Net zero talk has had no obvious impact on a dramatic curve of liquefaction capacity over the last thirty years. America’s ambition to become a major LNG exporter adds a further layer of capacity growth projected to the mid 2020s.

Does the constraint perhaps operate from the demand side? In light of its fulsome commitments to climate policy it would seem obvious that Europe must be seeking to reduce its reliance on both foreign and domestic gas. Along with coal, Europe will in the foreseeable future have to give up on gas too. You might imagine that it would be shrinking its gas transport capacity to a bare minimum. That would then expose it to sudden demand shocks like that in 2021. This is the scenario of the “energy dilemma”. Unfortunately, the reality of Europe’s gas supply situation is almost precisely the opposite. Much as wind and solar have grown in importance, their share of electricity generation was matched in 2020 by that of gas, which since 2014, on the back of ultra-low prices, has seen a dramatic comeback. As Europe’s domestic gas production has fallen sharply in recent years, to fill the gap, Europe has relied on imports. To transport those supplies the EU already in 2010 had pipeline and LNG terminal capacities far in excess of its needs. But rather than treating that as a reason to minimize further investment, it has doubled down. Nord Stream 2 is just the most notorious of a suite of pipeline and LNG terminal projects.

Source: Global Energy Monitor

To reiterate, this investment to the tune of c. 10 billion euros has taken place since the Paris agreement was signed in 2015 and despite huge existing over-capacity. Furthermore, far from public policy squeezing private investment, public money has been thrown into Europe’s gas infrastructure.

Source: Global Energy Monitor

In 2021, that situation is changing. Public funding is being withdrawn. But these long-overdue decisions cannot be made responsible for the gas market imbalance of 2021.

The idea of a secular retreat of fossil fuel investment under the sign of an “energy dilemma” simply misses the mark. Over the last fifteen years, whilst it was trumpeting its commitment first to the Kyoto climate protocol and then to the Paris agreements, the EU made a substantial physical and financial investment in integrating its system of gas supply with global energy markets. Since the early 2000s, the aim of EU gas policy has to been to create a “liberalised” gas market, that amongst other things would reduce its cold war-era dependence on supply and pricing through contracts with Russia. Furthermore, the EU has moved to pricing gas not on the basis of long-term supply contracts but by way of the spot market. Seen from this point of view, the huge capacity of pipelines and LNG terminals is not redundant. It is the physical infrastructure that has enabled Europe to play the global gas markets.

Gas is less polluting than coal, but this strategy was not driven by the desire to minimize CO2 emissions, but to minimize energy costs and achieve energy security. This is a crucial point to emphasize. Shifting back to gas after 2014 played a key part in Europe’s climate policy in the years immediately following Paris. And it is through gas that the global energy shock of 2021 has arrived in Europe. But gas was not adopted by Europe’s electricity generators to minimize CO2 emissions. Until recently, the cost of emitting a ton of CO2 was so low that electricity generators in Europe had little reason to consider the climate implications of whatever fuel they were using. It was not until August 2018 that the price of emitting one ton of CO2 for a European power plant rose above 20 Euros. The aim of investing in gas import capacity was to take advantage of low fossil fuel price world. Thanks to ultra low global gas prices, since 2014, according to IEA estimates, the EU’s strategy of relying on global markets saved $ 70 bn. But by the same token it was also exposed to the shock suffered by the global energy economy in 2020. It is above all through the gas market that Europe and Asia were interconnected as arenas in the “global energy crisis”.

**********

In 2021 the serious electricity shortages in both China and India were an essential part of the energy crisis narrative. By mid October 2021, India’s coal supply situation was critical. “17 thermal power plants had zero days of coal stocks as of October 10, with production and despatches from coal mines falling short of demand. Another 26 plants had stocks for one day. … that’s about 31% of the power from coal-fired thermal power plants.” But the operative term here is coal. Unlike in Europe and the US, China and India’s main source of electricity supply is burning coal. Between the two of them, they entirely dominate the global coal market. They also, however, rely for the most part on domestic sources of coal. In India’s case, domestic production covers 95 percent of power needs. How then was this part of a global energy crisis?

In the case of India, it really wasn’t. The shock of rising global prices would not, by itself have propelled a crisis in India. The Indian crisis that did occur could have occurred without any outside forces involved. Furthermore, in the course of 2021 India uncoupled from the global energy system. So, its local difficulties in fact relieved pressure on global markets. The reason that India does belong as part of the global narrative is that its national crisis resulted from the common experience of uneven and haphazard recovery from the COVID crisis. As India’s recovery began in earnest in 2nd quarter of 2021, India’s largely national electricity system came under huge pressure. It was, in effect, an intense, local supply-chain crisis.

India can certainly be described as facing an “energy dilemma”, but net zero is not the issue. The question is how to organize the supply of power to hundreds of millions of low-income consumers. Who in the supply chain should bear the costs and risks? Coal India the giant mining conglomerate sells coal to generators, who burn it and sell power to distributors who supply power to business and retail customers at rates, set by regional governments, that are amongst the lowest in the world. The fixed prices squeeze the finances of distributors. They, in turn, often fail to pay generators, leaving them unable to pay Coal India. Coal India retaliates by restricting the generators to delivery-against-payment, limiting their ability to build adequate stocks of coal. The dramatic reduction in coal stocks at the generators was less a symptom of coal shortages than shortages of cash.

The surge in global energy prices did no more than exacerbate this domestic squeeze. Given fixed local power prices, the surge in world prices caused coastal generators that normally use imported fuel to shut down, shifting load to inland producers, or to shift demand to Coal India, increasing pressure on limited supplies. The effect, as Reuters reported was actually to cut India’s demand for global coal, relieving pressure on global markets.

Could more coal have been supplied? Perhaps. But if so, the shortfall was not due to environmental concerns. Critics accuse the Modi government of milking Coal India’s balance sheet to help cover government deficits. Production has stagnated. As the economist M.K. Venu points out in The Wire, in 2016 the Modi government had sought to bring big private players into coal production. But the promised 130-150 m tonnes of production had not materialized. Why not?

The private sector was complacent because global prices of coal were consistently low, incentivising imports over investment in domestic capacity. Typically, private miners invest when global prices are high. As the private sector delayed coal production, the Centre also took its eye off the ball and did not give follow-up clearances for exploiting new coal blocks.

In any case, when the crunch came in 2021, Coal India was able to surge production considerably above 2019 levels. Production and deliveries were higher in September 2021 than in 2019. The immediate problem was not so much inadequate coal production, but the parlous financial state of distributors and generators.

********

If India’s energy crisis was part of the global crisis more in the way of sharing a common experience than in being causally interconnected, the reverse was true for China. The causes of its energy supply difficulties in early 2021 were highly idiosyncratic. But the causal ramifications for the rest of the world were dramatic.

The precise causes of China energy’s crunch are complex. There is no doubt that deliberate decisions by Beijing to regulate coal-fired electricity generation played a key part. In this sense this is where the energy dilemma narrative really bites. But the dilemma in question is once again rather different than the one commonly invoked. It is driven by a deliberate national policy to throttle coal use rather than any indirect effect on private investment and it plays out transnationally and by way of the spillover of Chinese supply constraints both from coal and low-carbon sources, to global LNG markets.

As one leading LNG expert commented in June 2021: “Rising electricity consumption has been in the spotlight since the start of 2021, driven by China’s economic recovery.” Normally this would be met by coal and renewables. But, “In the first four months of this year, gas-fired power generation jumped 14% year-on-year. Strong electricity demand has been a key driver for increased LNG imports in southern China in particular, as gas provides the critical peak-shaving supply into that market. With hydro generation in southwest China curtailed by lower rainfall and solar power output below expectation, Guangdong province has experienced a shortage of electricity imports. Tightening power supply options in China’s industrial heartland have come as power demand continues to rise on the back of solid export-led industrial growth and the early arrival of higher summer temperatures.”

China was not hitherto the leader in the global LNG market, or even the East Asian LNG market. “For as long as most can remember, Japan has been the world’s largest LNG market.” Unlike China or Europe, Japan had no other practicable way of accessing gas. “The country’s utilities and trading houses underpinned decades of LNG supply growth, signing long-term contracts that formed the bedrock of the industry.” Now in early 2021, China overtook Japan as the largest importer of LNG. It was that historic shift that triggered the remarkable escalation of East Asian spot prices for gas in the autumn of 2021. In Asia, however, the impact of those recored spot prices is easily exaggerated. Only around 35 percent of Asian gas is priced at spot prices. In Europe the situation was far more serious. There, 80 percent of gas pricing was on a spot basis. That is how the energy crisis spread to Europe.

*********

In the good times of low gas prices since 2014, Europe bought the cheapest gas on offer and diversified away from Russia. But when markets got tight, the boot was on the other foot. In 2021 Europe was competing with Asia for its gas and it was paying the price. This very illuminating graph shows the average prices paid by European and Asian consumers, weighted for the share that was price at spot rates.

Source: Peter Zeniewski

Ordinarily, to escape the squeeze on gas, Europe might have switched back to generating electricity from coal. But coal prices were elevated by the bottlenecks in China and India and by a surge in the price of emissions permits in the EU-ETS. This is how the green factor finally does enter the European story. The EU-ETS had long been a dead letter. But in early 2014 it had been subject to tough reforms. They tightened the supply dramatically. The full effect had not been noticeable at first because energy prices collapsed. Then in 2018 prices in the EU-ETS began to rise, hitting 60 euros per ton in 2021. At that point there was no switching back to coal.

Source: Trading Economics

*******

So the issue is not that post-Paris climate ambition depressed investment, narrowed margin of supply and created conditions for spike. That entirely exaggerates significance of green policy. What 2021 exposes is that the green push since 2015 has been enacted against the backdrop of a regime of low energy prices set by the price collapse in 2014. On both sides of the Atlantic, the extremely low price for gas delivered a series of easy wins for climate policy. Emissions in the US power sector went down even under Trump. And then the switchback of 2020 hit, China’s gas demand surged and everyone was found out. The lesson is not that the EU has been pushing green too hard, too fast. The lesson is that if China and the rest of Asia embark on a huge dash for gas, Europe’s investment in market-based gas import model is very high risk. The logic of diversifying away from Russia was good, until you ran into China. The solution is not less commitment to the energy transition but more. But here too, the 2014 price shock has had its effects. Though seen from the side of power generation, the shift to wind and solar has continued, viewed from side of finance, investment in renewables in Europe has been flat since 2015. In 2019 it actually fell sharply. This was less catastrophic than it seemed because of the fall in the cost of solar panels. But it was far from the dramatic acceleration that might have ben hoped for in light of rhetoric.

Goddamn Adam, you really are an army of grad researchers, not a single person. How do you manage to put out solid pieces, consistently, day-after-day?

Very good analysis on energy market.However in India's seasonal factor played a major role in coal shortage.During monsoon months coal mines are unable to produce as much due to water logging.This year was a very unusual late monsoon withdrawal.