As the G20 and COP26 convene in Europe, there is crisis talk everywhere.

The climate crisis is front and center, of course.

But, in the weeks before the summits convened, another crisis surged to the top of global attention.

We are - we are told - living in the midst of an “energy crisis”.

Oil has surged above $ 80 per barrel, its highest price since 2014. Gas prices in Asia have spiked at the equivalent of over $ 300 per barrel. In the UK, a dozen retail gas suppliers failed, leaving 2 million households in limbo, uncertain who would be supplying their homes.

Since hitting peak anxiety in late September to early October, the panic has eased somewhat. But, last week President Macron warned of an energy crisis. And, at the G20, Bloomberg quoted Amos Hochstein, Biden’s top energy diplomat, as saying, "we found ourselves in an energy crisis”. According to Bloomberg, this is a“broadly held view by big oil consuming nations”. In the context of the G20 that means Japan and India. In a thirty-minute State Department briefing on October 25, Hochstein used the word “crisis”, 11 times.

Meanwhile, google searches of “energy crisis” are at a five-year high. And stagflation is one of the hot memes on the terminals.

Source: Google Trends

The point of emphasis is different depending on where you are in the world. In the US, as ever, the main preoccupation is petrol prices. In the UK and Europe the main worry is gas. At the G20, the US apparently ganged up with Japan and India to pressure Saudi and Russia to raise oil production.

But, how seriously should we take this talk of “energy crisis”?

************

The evidence for an interconnected energy crunch of a structural kind is not strong. Columbia’s energy policy unit headed by Jason Bordoff, ex of the Obama administration, has published several reports pouring cold water on the idea of a general squeeze. So has the CER.

What is particularly contentious is the idea that this price-surge has anything to do with a big push to net zero.

The argument goes as follows. Net zero ambition has shaken confidence in the fossil fuel sector. Investors who lack confidence in the future of their industry don’t invest. Lack of investment means that we don’t have the capacity to deal with surges in demand. Behind the energy price volatility, on this very contentious reading, lies an investment strike. The implication is obvious. To avoid further spikes in energy prices, we thus need to back away from radical net zero policies and build some extra gas capacity, as a transitional solution.

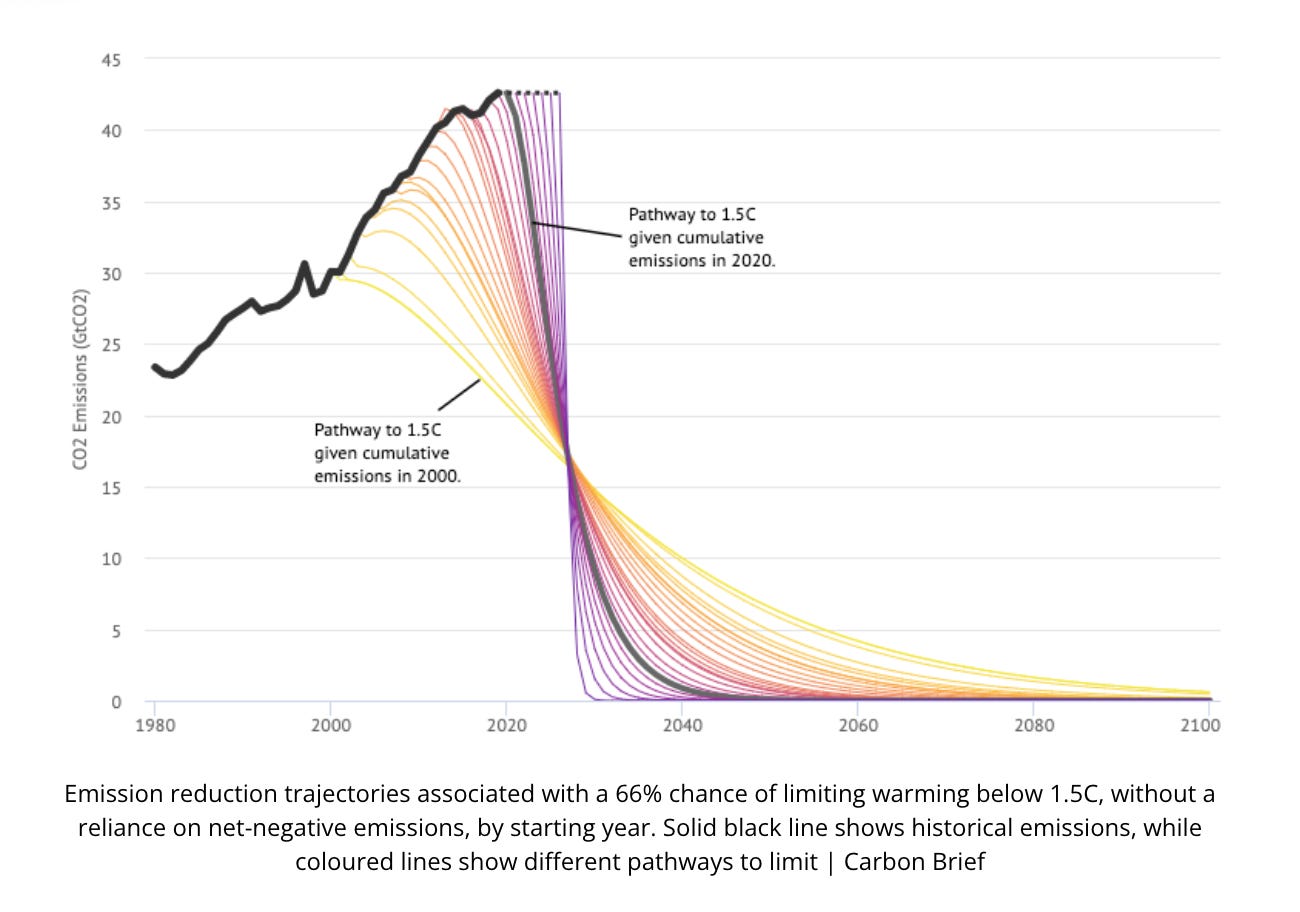

How dangerous this kind of argument is, how little we can afford to make any concessions to the gas lobby right now, is brought out by the recent batch of graphics showing the vertiginous path of decarbonization to which we have condemned ourselves.

Source: Carbon Brief via Open Democracy

For good reason, this transparently self-serving idea has been attacked on Bloomberg, the Washington Post, by the IEA and indeed by Hochstein of the Biden administration who insisted that his talk about an energy crisis should not be misread. It has nothing to do with a push to net zero.

As Hochstein puts it:

“there is this notion out there that – I would say a false notion that ties the current crisis to the energy transition. And I want to be very clear. There is – the energy transition is not what caused this crisis. There are a number of contributing factors. But some of the leading factors – not all of them, but some of the leading factors have to do with global weather patterns that have significantly affected the energy system. We had a drought in China and a drought in Brazil that affected hydropower in a fairly significant way. We had hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico that affected deliveries into Europe, two of them in fact back to back. We’ve had fires. So the weather pattern – the climate is changing. We are in a climate crisis. And in fact, if I learn anything from this crisis that we are facing – and I think it’s a real crisis, right, because oil prices are extremely high, coal prices are high, natural gas prices are high; this is having an impact of a chain event on other metals production where prices of metals are going up; those are inputs into renewable energy.”

***********

So what is going on? In the New Statesman this week I argued that we are facing a new kind of crisis - a political crisis of the energy transition. The real effects of the energy transition are as yet modest, but the politics are already live. The fightback by the gas lobby is in full swing. It will be one of the big struggles of the next decade.

In making the case, I invoked the left-wing Polish Keynesian Michał Kalecki to argue that crisis-talk is being instrumentalized for the defense of business interests.

In 1943, just as Keynesian thinking began to take hold in government in both the UK and the US, Kalecki made the prescient argument that faced with the new government activism, the business lobby would retreat to a defensive position. At the depths of a cyclical downturn they would welcome state intervention to rescue the economy. But as government spending built up, labour markets tightened and employer control both over their factories and the agenda of economic policy was challenged, the same business lobby would resort to arguing that excessive government spending and big deficits were bad for confidence. Lack of confidence in turn impeded investment and growth. Talk about “confidence” would thus become the battleground for an effort to preserve an “equilibrium” of unemployment. Confidence I take to be the flipside of crisis-talk in our current moment.

Kalecki with his Marxist background realized that even as the technocratic vision of a government-managed economy emerged, it would face powerful opposition. Full employment, as promised by Keynesians, would never be achieved. The world would remain in Kalecki’s words in an “artificial restoration of the position as it existed in nineteenth-century capitalism”.

The analogy to climate change is not perfect. The climate crisis is not generated by cyclical swings, but by the growth process itself. But Kalecki’s analysis of the confidence game played by business lobbyists is prescient. And the vision of being trapped in an “artificial 20th century of fossil-fuel-dependence” by the rearguard action of business, is haunting.

For those reasons I think we should dub 2021 the first “climate Kalecki” moment. It should go alongside the “climate Minsky” moments we have been learning to analyze in the sphere of macrofinance. This may be our first but I wager that it will not be our last climate Kalecki moment.

Clearly, diagnosing the situation in 2021 is important. But the broader issue at stake here is how technocratic strategies of economic management - whether with regard to employment energy transition - can actually be brought to bear in a political economy riven with contradictions and conflicting interests. And in particular what role the diagnosis of crisis plays in such a setting.

The argument in the New Statesman article is directed against business lobbyists and their claque. But it also marks a point of difference to some folks on the left who are trying to make sense of the current conjuncture.

*********

One of the left intellectuals I most consistently enjoy reading is Richard Seymour. For anyone who enjoys a blend of Marxism and psychoanalysis, his Patreon account is highly recommended. Seymour is also one of the leading lights at Salvage magazine.

Seymour has done two interconnected newsletters on the current moment. One of the energy crisis. One for the opening of COP26.

Contrary to the line that I have adopted in the New Statesman, Seymour argues that though the symptoms of stress in energy markets may be dispersed, the crisis is fundamentally deep and real. As he says, crises often take this form.

“One problem. This is how structural crises always manifest themselves: as moments of intense overdetermination, gatherings of apparently unrelated shocks.”

The key reference here is to Althusser’s 1962 essay on overdetermination. (NB this is a TRULY dense work. Not for the fainthearted.)

Nor, in Seymour’s view, is the reemergence of a real crisis to be regretted, because it is at such moments that elite consensus come apart, the climate movement gains real purchase and can force a change in agenda. This is a classic Marxian idea, that out of crisis, moments of emancipation emerge.

Or as Seymour puts, it: “As a moment of intense overdetermination, this situation is also a moment for political intervention … it is in the nature of crises that the ruling class doesn't have to get everything its own way.” “Like all successful movements, they have exploited and collaterally benefited from crises that are not directly related to their issue. The strategic and sectional divisions within the ruling class can usually be prised open by militant movements”

As Seymour argues, the current moment in climate policy may disappoint the movement, but against the backdrop of what is to be expected, it has to be understood as a triumph:

“the problem to be explained is not ‘failure’. Failure would be the default, the normal state of affairs. The odds are stacked heavily against human survival. What needs to be explained, particularly if we want to know what to do about COP26, is success. For, as I’ve said, despite the forces arrayed against us, the legal and consensual parameters of climate action have shifted. Three big waves of environmental action –– the movements of the late 1980s, the action around COP15 and after, and the upsurge of school strikes and direct action since 2018 –– have combined with improving climate science, the growing economic costs of climate change, and alarming droughts, wildfires and extreme weather events, to force the environment up the agenda. ….

Climate protest has forced the fossil industry to junk its overt denialist apparatuses and pretend to be green. Most big businesses crave association with the rising ecological consciousness …

Capitalist states overwhelmingly accept ‘the science’ and, with the use of increasingly efficient renewable energy sources and the ‘transitional’ fossil energy of natural gas, some overdeveloped states have begun to cut emissions.

In the last decade, the Green New Deal has gone from being a marginal concern of some economists and ecologists to being a globally mainstream policy idea. The Biden administration has embraced some of the policies of the Left ….”.

All of this is true and I agree, it is utterly surprising. But what about the current moment? What about the relationship between the energy crisis and this struggle between social movements and power.

In this regard Seymour remarks:

“A far-sighted ruling-class response”, to the current energy crisis, “will probably be to accelerate the transition to renewables and more energy-efficient buildings, transport and supply chains. There may even be competition over who transitions fastest, and trade wars over rare metals. But the point will be to continue to expand, in perpetuity, the extraction of human labour and the metabolisation of the natural environment.”

The problem that Seymour sees is not in the energy crisis as such, but in the successful realization of green-washed coping strategies. These new growth model will be badged green and sustainable. But they will, in fact, “accelerate the ecological crisis eroding even the material infrastructure of capitalism.”

It is here that we differ. Remarkably, if I read him correctly, Seymour is more sanguine than I am. He seems to be suggesting that thanks to the pressure on its flanks, green modernization is now mainstream and so the energy transition, despite all the current crisis talk, is unstoppable. I am more worried.

This you might say is simply a judgement call. We may differ in how we assess the vigor of the fossil-fuel rearguard. It may be a matter of a European and an American perspective. But I actually think it opens up a bigger issue, which is how we think crisis and its impact on the balance of political forces.

In Seymour’s analysis, crisis is an opening. I am not so sure.

In the recent political economy of both the US and Europe, crisis has all too often been a generator of compulsive and highly conservative logics. Think of “too big to fail”, or the threat of bond market vigilantes, invoked to impose austerity. Or the meltdown that we saw in financial markets in 2020.

Out of a diagnosis of crisis, threat, insecurity, slippery slopes, tipping points, a powerful case for conservatism has been fashioned. Is this not what is happening in 2021 too? An attempt is being made to declare the fossil fuel energy system too big to fail. If you let us go, then the supply of gas and electricity to main street will either fail or become exorbitantly expensive. That is the threat that we have to face down.

*********

I’m a self-confessed liberal Keynesian. My kind of politics, focused on present-minded crisis-fighting no doubt predisposes one to downplay the structural elements in a moment of tension like the one we are currently living through. (Yes I can hear the echoes of Anderson’) It predisposes one to focus on the contingent factors and to seek to disaggregate different lines of causation that are in play so that they can be addressed in a targeted way. That is what I am advocating in the New Statesman article. But, I would insist, my skeptical debunking approach to energy-crisis-talk is not picked out of thin air. It is based in a strategic assessment and a structural diagnosis of the challenge we face. It is based, by way of Kalecki, in a structural reading of the interests that crisis-discourse serves and the need to resist the confidence tricks with cool heads and sharp analysis. Above all it is orientated towards the dynamic, constantly evolving challenge of the energy transition.

Given the drama of this graph, there is no need to exaggerate our difficulties.

Source: Carbon Brief via Open Democracy

*********

If you would like to support the Chartbook project, there are three subscription options:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

The 1.5 degree pathway is clearly unrealistic at this point. But 2 degrees is easily achieved if we get to net zero by 2050 or 2060. So it seems that ultimately warming will be around 1.75 degrees give or take. Prior to 2015, the target that was widely embraced was holding temp rise to 2 degrees, but it was shifted downwards to 1.5 degrees in 2015. This coincided with revisions to projected warming that expanded the carbon budget making 1.5 degrees at least theoretically still feasible (the prior IPCC projections made a 1.5 degree target no longer possible). To what extent were these changes interlinked versus two seperate processes?

I imagine we will transition off of ICE vehicles far more rapidly than was expected even a few years ago, the Hertz purchase of Teslas and the soaring production and sales of EVs in the EU augur well. But to hit the 1.5 degree target is going to require significant DAC and negative emissions in the back half of this century. That is primarily a political question to be dealt with by the next generation. From both an engineering and cost standpoint, spending 1% of GDP for DAC annually will be more than enough to achieve the goal.

Professor Tooze,

Thank you for sharing your perspectives. I believe that you've made a persuasive case that neither the widely expressed fears of inflation nor those of an “energy crisis” are well-founded, at least as currently framed. Templates using the 1970s or the 1930s don’t seem very strong, and your argument for a post-Korean war precedent seems more in order. Also, efforts to stoke fears of inflation and of an energy crisis undoubtably provide attractive narratives for conservatives; conservatives in the sense of those who want to ignore the implications of climate change and extend as far as possible our fossil fuel regime and its political economy. But allow me to pull back the focus from the immediate present and ask some questions based upon some impressions that I’ve developed. I want to explore how my conjectures fit into your analysis.

Recent figures (2019) from the U.N. reported that in 2019 the planet has 7.7 billion inhabitants, which is likely to rise to 8.5 billion in 2030 and nearly 10 billion in 2050. Barring a “Green Revolution,” an unanticipated practical, technological break-through, won’t the world’s agricultural resources be pushed to such limits that some long-term inflation of food prices will become significant and persistent? Also, given the increase in the severity and frequency of extreme weather events, isn’t there a marked risk that both total production may decrease and that distribution systems may be adversely affected (ports, rail, roads, etc.) and thereby continually fuel price increases in food and other consumer goods? (I’m thinking of hurricane damage to ports and landslides closing roads, such as we suffered a couple of months ago here in Colorado). You might dub this line of inquiry the “sooner or later Paul Ehrlich has to be right” conjecture.

As to “the energy crisis,” while it’s not caused by the conversion to low-or-no-carbon energy regimes, can we, via any current regime, meet current energy demands? The obvious answer is that we can meet the needs of all the developed countries and developing countries (including India and China) if we burn unlimited fossil fuels. But assuming we are not that foolish, as we taper fossil fuels, can we supply sufficient energy to fuel continued growth in the U.S. and abroad such that India and China (for instance) can close the gap with the developed nations even as those nations achieve the economic growth that they desire? In other words, I fear a significant gap between our current ability to generate “clean energy” and current (and immediate future) demands for energy. So although green energy isn’t the cause of current energy shortfalls, do we have the ability to continue to move away from fossil fuels given our current rate of consumption? (Not to mention burgeoning demand in nations like India and China.)

In about 1977 or thereabouts, John Kenneth Galbraith gave a public talk at the University of Iowa, and I was lucky enough to get to ask him a question. My question was (or was intended to ask) how our economy in the U.S. would prosper in a world of energy conservation, oil shortages, and the like. In short, in the face of decreased economic activity in general, could our current economic regime continue to prosper? Galbraith waved-off the concern implicit in my question with something along the lines of “it will all work out.” As it turned out, Jimmy Carter, “malaise,” and energy conservation were soon out, and Ronald Reagan, “It’s Morning in America,” and (after a wrenching recession) freewheeling energy consumption were back in. My question seemed only so much doom-thinking. But now this question is back, gnawing at me again. If, as Vaclav Smil, William Ophuls, Thomas Homer-Dixon, and many others have suggested, there are hard ecological limits on the amounts of stuff we can produce and consume and the amount energy that we can produce (and that the environment can accommodate) given current technology, isn’t contemporary consumer capitalism—and the political regime that's built upon it—looking at a rocky future?

Thanks very much for sharing your very informative and provocative (in the best sense!) thinking about these topics.