Chartbook 463: Polygloom - What's wrong with Germany?

The winter is coming and Germany is engulfed in a gloomy fog.

Since before COVID, economic growth has halted.

Source: FT

Stories of industrial failure and fearsome Chinese competition multiply.

We are in the kind of mood when different sorts of bad news resonate with each other, compounding and overlaying each other. The result is a sense of profound malaise, made worse by the threat of even worse things to come.

What happens if Trump really pulls out of NATO? What if, the second China shock and the decline in German industrial production, are just the beginning?

Source: FT

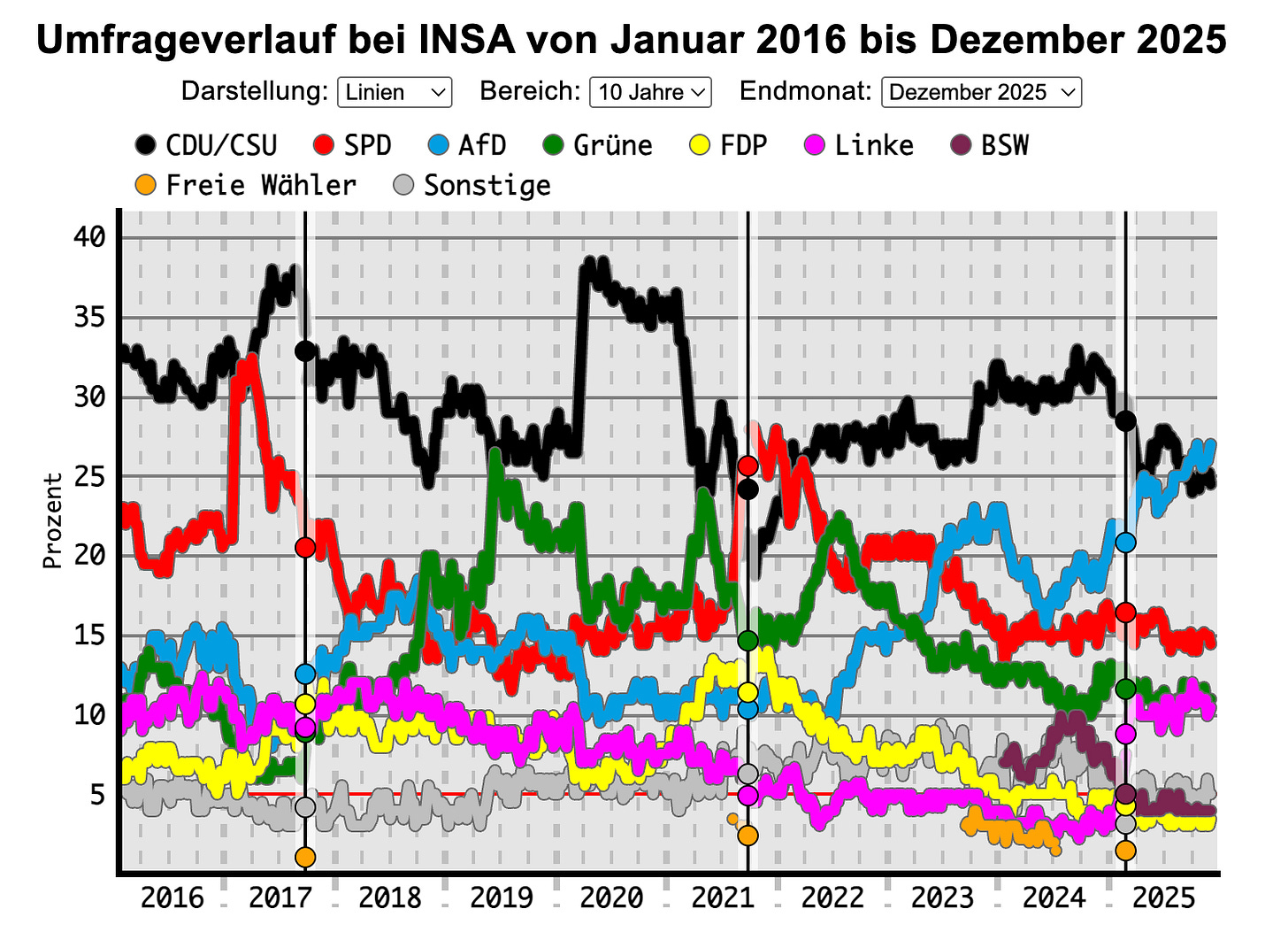

What if, Germany in the 2020s really is the “sick man of Europe?” And what if, on the back of that crisis, the far-right AfD continues its march towards the front of German politics? How does German democracy function, if the far-right commands one third of the electorate?

Source: Dawum

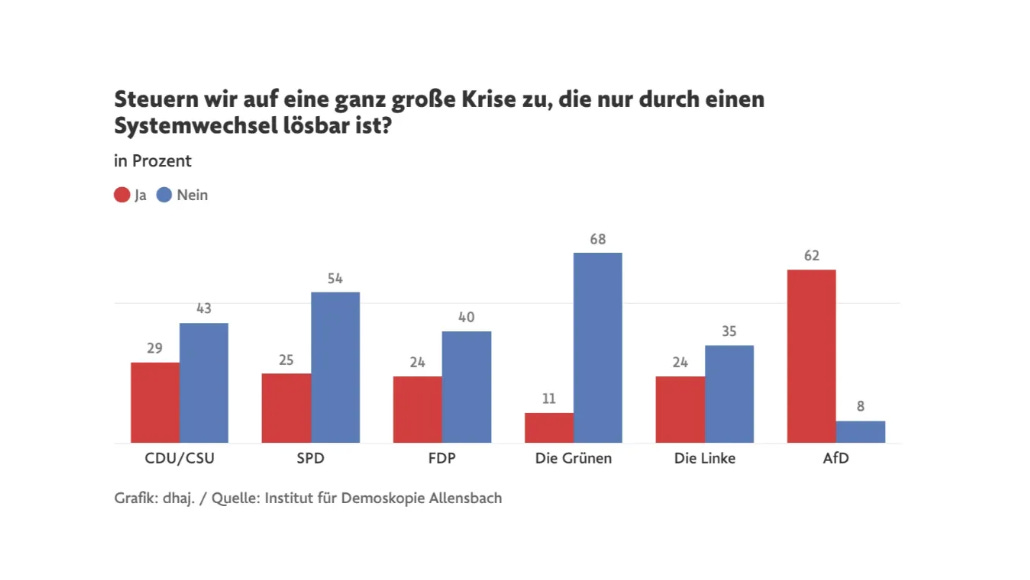

One thing that is distinctive about the AfD’s electorate is that they are profoundly pessimistic not just about their own personal circumstances, but about the outlook for German society as a whole. Back in 2023 62 percent of AfD voters said that they saw Germany headed towards a major crisis that could be resolved only through “regime change” (system change, Systemwechsel). Then, they were the polar opposite of voters for the Green party. Two years later, the apocalyptic tone of much media coverage is making the arguments of the AfD for them.

Source: Chartbook 235

In the pages of the FT, the sense of an economic downward slide is summed up with the question: “Can anything halt the decline of German industry?”

The mood is one of polygloom - a heterogeneous complex, defying summation by a single causal logic, menacing, a whole that is worse than the sum of the parts. Any bit of bad news, whether it is about trains, VW, crime, a collapsed bridge or the national soccer team compounds the general sense of malaise.

I was first struck by this agglomerative tendency a few summers ago on a TV panel about what was then called the “inflation shock”. A few years later, despite a change of government and the promise of huge public investment to come, the sense of a compounding crisis and impending doom, is, if anything, even more intense.

This isn’t the first such moment of collective gloom in Germany’s recent history. In the late 1990s the talk was of “blockierte Gesellschaft” (blocked society).

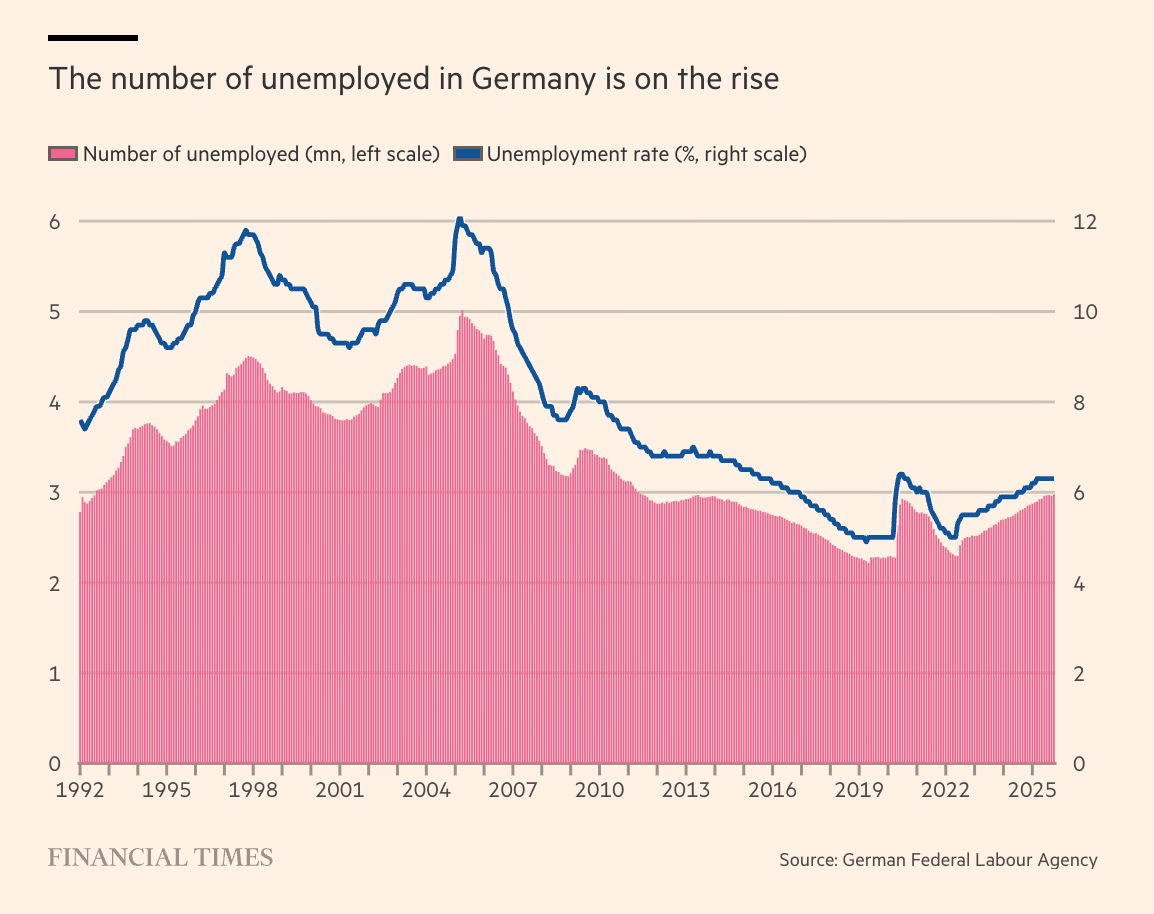

In the late 1990s, there was also a growth slowdown. But the immediate issue was mass unemployment - following reunification - and the dysfunction of the social insurance and unemployment insurance system.

Source: FT

But the sense of “blockage” in the late 1990s came not just from the labour market.

There was also a sense that Germany was missing out on the trend of neoliberal reforms then set, above all, by the US and the UK - the double whammies of Reagan-Clinton, Thatcher-Blair.

Germany’s Red-Green government faced foreign policy tests in the Balkans and then the surprise election of Bush, 9/11 and the Iraq war. This was the moment when American conservatism began to seriously diverge from bien pensant European politics. It was the moment when intellectuals like Derrida, Habermas and many others declared a “divided West”. In retrospect, it is clear that it the beginning of a trend which culminates in the second Trump administration.

The response from the Schroeder government was a more independent foreign policy. And, under the slogan, Agenda 2010, the Red-Green government pushed through a uniquely sudden and severe labour market and welfare shock. Then, under a continuity of SPD leadership at the Finance Ministry from 1998 to 2009, Berlin with the loud backing of conservative state-level governments (notably in Bavaria), embarked on a fiscal consolidation push that culminated in the infamous “debt brake” amendment to the German constitution in 2009.

Wolfgang Schäuble the legendary CDU finance Minister in Angela Merkel’s second government, did not invent the “black zero” fiscal policy. Schäuble inherited this vision of non-discretionary fiscal policy, which is now seen as overshadowing Germany’s macroeconomic development since the 2010s, from his SPD-predecessors of the 2000s.

Meanwhile, German capital globalized. Germany’s big banks went on disastrous adventures in London and Wall Street. Germany’s high-end manufacturing engaged in a highly profitable program of outsourcing and globalization. This produced growth, strong exports, healthy profits for the elite and high-paying secure jobs at least for a minority of the industrial workforce. It also produced rapidly rising inequality. Germany’s pre-tax Gini coefficient rose more rapidly than practically anywhere else in the West in the 2000s. This was held in check only by a means-tested welfare system operating at increasingly frantic and strenuous pace.

The shock of the “Schroeder reforms” dealt a blow not just to German society. It also split the German left-wing, giving rise to Die Linke, which now commands 10 percent in the polls. Fast forwarding to the recent past, for the social democratic party of the 2010s the Schroeder era was an episode to distance oneself from. The task of social democracy was to offer a more equitable deal. Scholz and his team stressed dignity and respect and, by way of Next Gen EU and the COVID response, began to shake off the debt brake. The Klingbeil and Merz coalition inherited that momentum and by way of a cynical parliamentary maneuver earlier this year opened the taps for truly large-scale spending.

The times have certainly changed.

Unlike in the 1990s the most immediate challenge facing Germany is not unemployment. Though jobless figures are inching up, the labour market remains tight. There are endless complaints from employers about the lack of skilled labour. The stagnation of the German economy in the current moment is so worrying because it intersects with three other problems.

The first is the radically changed geopolitical situation, with Russia an immediate threat and the United States sliding into a crisis of its own and increasingly unreliable as a backer of NATO. (More on this and the German reaction in a newsletter to come over the holiday break). Germany needs to rally its industrial capacity and collective will and Europe needs Germany. It does not help to have German industry pervaded by a sense of crisis.

The second is the rise of China that turns globalization from a general process of economic expansion and integration from which Germany profited, into a massive and direct threat to the German industrial base.

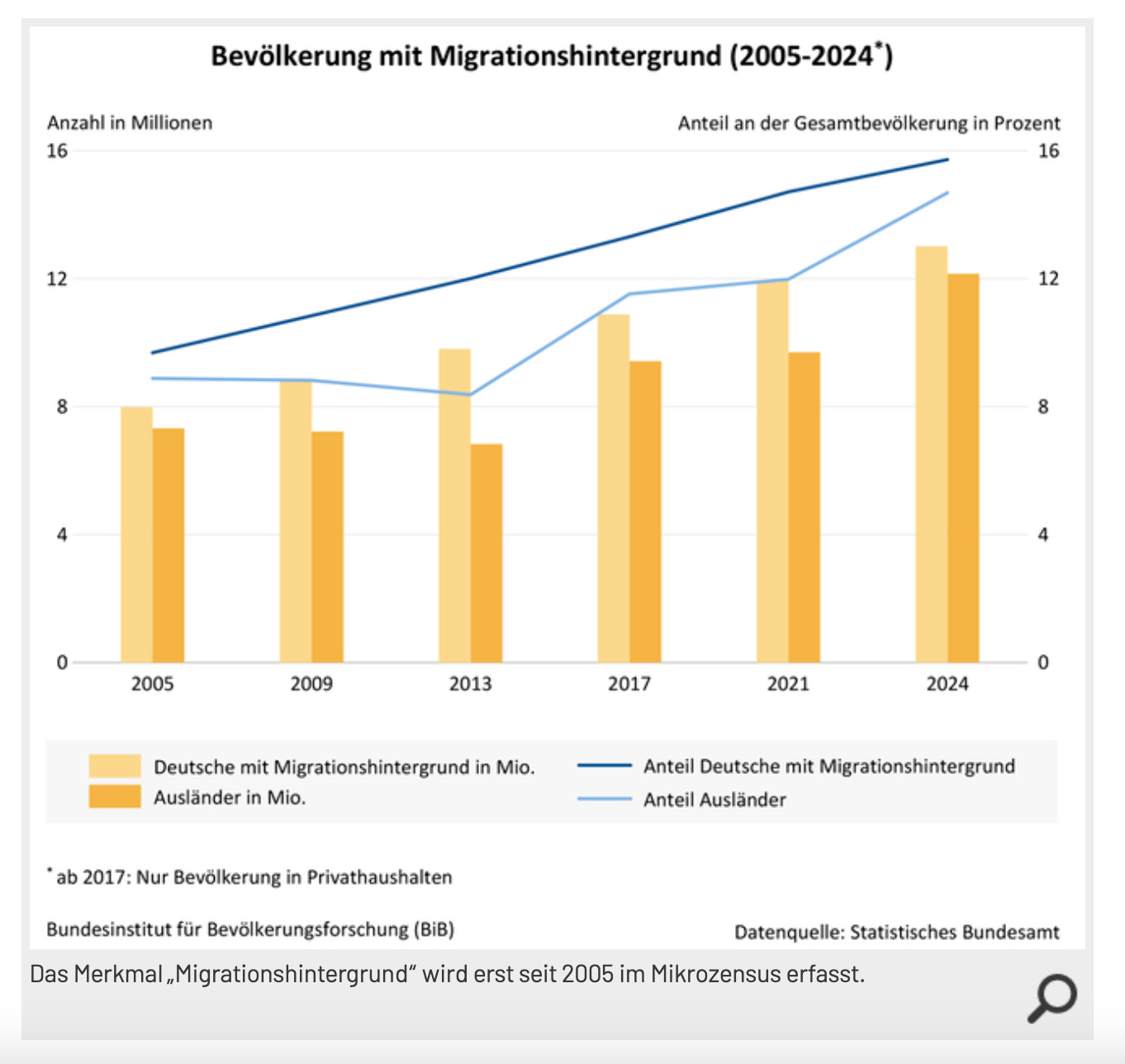

The third challenge is from the far-right. Never in its history has the German Federal Republic faced such a large and systemic political challenge. The AfD’s surge has many drivers. But it is impossible to escape the conclusion that its basic motivation is the profound dissatisfaction on the part of a large minority of the German population with the kind of country Germany has become. German reunification reestablished Deutschland (as opposed to the separate identities of FRG and GDR) as the central reference point of nationalists. That nationalism has different shades, but the right-wing variant is defined above all by its opposition to the secular increase in the diversity of German society, whether in the form of naturalized Germans with family backgrounds of migration, or in the form of foreign migrants living long-term in Germany. This transformation is by any standard dramatic and must be taken seriously if one is going to come to terms with contemporary Germany.

In 2025, the German population currently stands at roughly 84.4 million people, of those, roughly 25 million are in one way or another people of migrant heritage.

Source: BIB

“Deutsche mit Migrationshintergrund” refers to German citizens who either themselves were not born with German citizenship, or have at least one parent who was not born with German citizenship. There are 13 million “migra”-Germans. 12 million foreigners live in Germany and fall under the category of Ausländer.

To put those impressive numbers in perspective, at the time of unification in 1989 there were 62.7 million people living in West Germany and 16.4 million in the East. The migrant population of Germany today outnumbers the original GDR population by 50 percent.

A shift of this scale and drama demands a structural response. That is what the voters of the AfD want. And the party feeds them populist xenophobic slop. But what is the answer of the centrist parties?

As it should have, the newly unified Germany spent lavishly on the integration of East Germany. By contrast, Berlin’s investment in the giant migrant population that now makes up a much larger share of the population has been grudging and inadequate. The result is visible in the social inequality figures, in educational surveys and in every German town and city. Rather than offering a constructive and generous set of policies integrated with the CDU’s broader program, Chancellor Merz resorted to “dog whistle” politics, referring backhandedly to his commitment to cleaning up the Stadtbild of Germany’s cities.

In light of all this, it is easy to fall in with “polygloom” and to offer a very grim structuralist reading of Germany likely trajectory.

By way of counterpoint I recommend two pieces by Martin Sandbu in the FT. The first is a characteristic precise analysis of why Germany’s economic underperformance is actually something of a puzzle. The apparent underperformance of German industry is out of proportion to the most likely drivers of that malaise. Germany is not that much more export exposed. Its pattern of exports is not that different from its European neighbors. The reason that its industry is doing so badly is anything but obvious. The second piece is sourced from answers offered by folks from acrossthe serious-minded econ world.

The upshot of this collective sifting of the economic data is, at least potentially, optimistic. The remarkably gloomy figures for German industrial production may, in fact, capture an ongoing shift on the part of Germany’s industrial firms away from making things to delivering high-value services. This is not so much deindustrialization as a reconfiguration of what industry means. If this is the case it is exactly the right direction for Germany’s high-wage, high-productivity economy to develop in. Germany should embrace, accelerate and support change.

The second key point is that Germany’s actual problems may, as much as anything, be home grown.

many readers seemed to endorse my speculation last week that some of German manufacturing’s recent deeper than average decline is due not to unforgiving export markets but to a domestic market in the doldrums. And whose fault is a weak domestic market? As Erik Nielsen writes to me: “To argue that Germany’s roughly [10 per cent of GDP] decline in public debt (while others increased their debt) would have no impact on [domestic] demand seems a stretch to me.”

The reference here is to the baneful impact of Germany’s highly restrictive fiscal politics which, since 2009, have depressed public investment and aggregate demand and whose impact - speaking of Stadtbild - is also painfully obvious in everyday life across Germany.

The sources of Germany’s insecurity may be diverse, but investment is a polysolution. Germany desperately needs to be investing in its future, it needs equipment of all kinds. It needs infrastructure and it also needs to invest in human capital. Back in October 2023 in the pages of the FT, I made the case for coupling investment not just to the Bundeswehr budget or rail infrastructure, but to the social and human needs of an increasingly diverse and divided society. For all the emphasis in the current moment on tanks and rail, that still seems to me to be right. In particular it is the only kind of investment that offers any immediate hope of addressing the threat from the political right. There are racist and xenophobic people in Germany. But there are also reasonable Germans who are tempted to vote for the AfD, because it is in their view the only party that recognizes and addresses the radical changes that have taken place in the last generation and a half. The AfD’s answers are terrible. But the centrist parties have failed adequately to address those questions in their own terms. It should be a top priority of public investment to address the most painful choke points and trade-offs, whether in education, housing or health care.

Such a shift in priorities involves a wholesale political rebalancing. The Merz-Klingbeil government is anything but an inspiring vehicle for political hope. But the game is not up. There are signs of movement in Europe. What is required, as it has been since 2008, is large-scale and sustained collective action. To that end, we should be grateful to Sandbu and his correspondents for their serious-minded effort to replace gloomy fog with sharp and practical questions.

Thank you for reading this far. If you would like to support the Chartbook newsletter project there is no paywall, but I invite you to click below and sign up to buy me a cup of coffee once per month. It helps with the writing!

Surprised not to read about the sharp increase in energy costs thanks to the U.S.A. With LNG from America replacing gas from Russia, energy input costs in manufacturing have what, doubled ? How does that not hurt across the board ? A rise in energy costs is deflationary as more money spent heating, driving, & in production equals less money to spend elsewhere.

And why not point out that the destruction of the Nordstream pipeline by the U.S. enabled American high cost LNG to take the place of low cost Russian gas. The head NATO country bombed Germany & nobody wants to deal with the repercussions, not even Adam.

I love Adam Tooze’s writings but the above seems to have two blind spots regarding Germany’s downfall. One, already commented on, is the effect of Germany’s separating itself from cheap Russian gas via the NordStream bombing and via EU policies, and replacing it with expensive US LNG. Texas loves you, van Der Leyen and the whole Brussels bureaucracy, Texas loves you Mertz and the other unpopular leaders of European countries, you’re the best thing ever for Texas income.

The other is the result of a Russophobic aggressive militarization of Germany, the incipient Fourth Reich. More money for military is leading to more belt tightening for most of the populace which means more people voting against the incumbents, which means voting for AFD. The Greens are not viable as they are more militaristic than the conservatives and SDU, Linke is a possible alternative under its current new leadership but it needs to emphasize it’s anti-war stand. A German led war against Russia brings back too many echos of World War 2. Prosperity requires a Europe wide --- that includes Russia - security agreement.

The fact that pointing out the above two points leads to taunts about “Putin’s stooge” point to the paucity and self-limitation of thought brought about by European self-censoring and media policing.