Chartbook 222 Mood music: Talking inflation in Germany & managing the ambiguous politics of polycrisis.

I had the pleasure this week of talking inflation with a bunch of folks on Maybrit Ilner’s high-profile talk show on German public TV (ZDF).

Germany’s big talk shows - Maybrit Illner, Markus Lanz, Anne Will, Sandra Maischberger - are institutions in the German media scene. As TV goes, they are by far the best format I’ve worked within. The moderation is smart and well-informed. There is time for back and forth. The atmosphere can be intense, but the mood is generally collegial and the conversation often extends for an hour or more after the cameras are turned off. German viewers tend to complain that the format is overworked and the guests are predictable. I recommend that they check out the far worse fare that is served up by other TV systems.

***

You might think that inflation-talk in Germany would be all about central banks, price stability, the money supply and interest rates. But that is no longer the case. Apart from me, the panel consisted of Kevin Kühnert, the left-wing general secretary of the SPD, fast-talking conservative-liberal economist and podcaster Daniel Stelter, the CDU young turk Carsten Linnemann and the documentary social investigator and journalist Julia Friedrichs.

It was, to say the least, a free-wheeling conversation. But apart from anything it demonstrated that the monetary hegemony in German debates about inflation is thoroughly broken. I don’t remember the Bundesbank coming up. The ECB was barely mentioned.

You might say that this simply reflects the composition of the panel. Kevin Kühnert articulates an intelligent left social democratic position on prices. You get a sense of his position in this fun conversation with Mauric Höfgen about his new inflation book, Teuer (Pricey).

Julia Friedrichs’s work lifts the lid on poverty, class inequality and precarity hidden in plain sight amidst Germany’s affluence. It should be much better known in the Anglosphere. Guardian, NYT, FT commissioning editors should be asking Friderichs for Long Reads. This is a side of Germany you don’t see in conventional cliché-ridden coverage and yet it is essential to understanding the social pressures at work in Europe’s most powerful country. There’s your pitch …

Friedrichs brought the cost of living crisis into sharp and illuminating focus. Her opening statement was absolutely brilliant on the loss of agency induced not by one shock, but a rolling succession of shocks - life experienced as a permanent crisis.

Daniel Stelter might have been the voice you would expect to introduce the monetary dimension. On his podcast and website Beyond the Obvious he articulates a fairly straight ahead monetarism. He and warhorse Hans-Werner Sinn get along like a house on fire. But, as a straight-shooter and enthusiastic debater, Stelter also knows that all the monetary aggregates are currently pointing not up but down i.e. they are signaling an impending deceleration, deflation and recession. Take that with a pinch of salt. In any case, instead of talking about money Stelter went on an extended jag about the supply side, “Leistung” (performance), productivity, incentives etc - a conservative version of supply side arguments. We need more production and supply to match demand.

The CDU’s Linnemann, who formerly represented the German Mittelstand, was only too happy to get in on the act. Amidst the painful internal leadership battles of the CDU, he proposed to Kühnert that the CDU and SPD should end their partisan sniping and engage in an updated Agenda 2030 grand bargain for a new era of “reform”. Agenda 2030 would echo the now infamous Agenda 2010 that set the stage for Gerhard Schröder Labour Market policies of the early 2000s. Kühnert wasn’t buying.

***

Apart from the performative dimension of the whole affair, it was striking how little disagreement there was on the question of price-push inflation. As bait, Illner offered us the idea of “greedflation” but Stelter shot that down quite swiftly. As he pointed out, the issue was not more or less greed, but whether or not firms faced the pressure and the opportunity to raise prices.

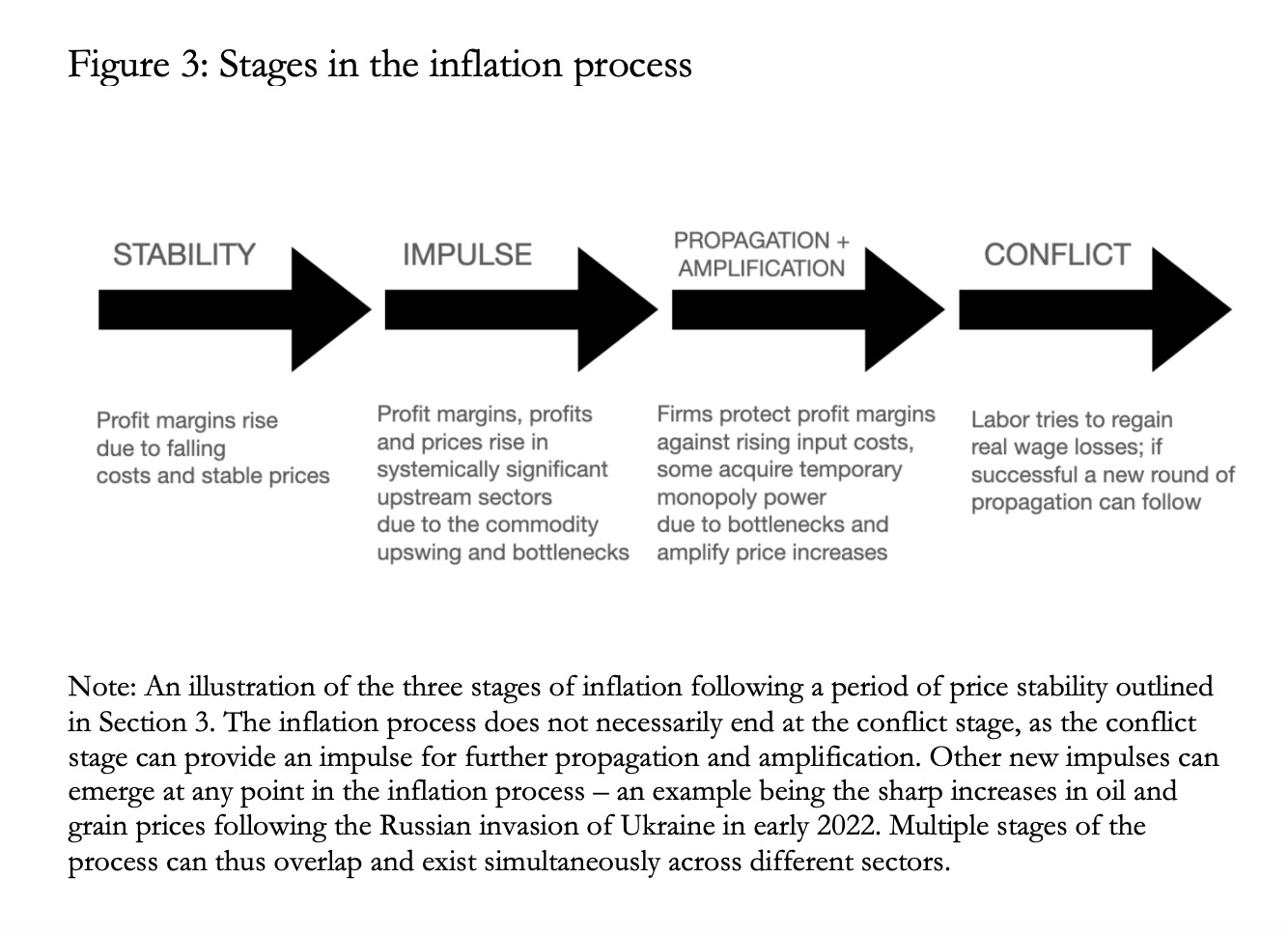

As Isabela Weber and Evan Wasner's paper shows, the analysis of inflation must become essentially historical in that it is about discreet and distinct decisions taken in the flow of time in response to particular opportunities and impulses, decisions which in turn change the conditions for further decision-making.

On Illner’s show, I even managed to get across the point that this might not be a general inflation in a classic sense at all, but rather a big price shock concentrated in certain key sectors from which ripples have spread to a limited degree across the entire economy. It is precisely the lack of a general and adequate adjustment, the failure of incomes to keep up, which drives the social crisis, while at the same time making the job of central bankers much easier. Despite their scaremongering, if the central bankers are honest they know that we are not facing anything remotely like a wage-price spiral. There is more than enough room for progressive politics to demand wage hikes, as Kühnert did.

***

What was striking about the conversation was less dogmatic ideological closure than a pervasive sense of national crisis. The title of the show was “Price rises. Economy shrinking - Is Germany getting ever poorer?” (Preise steigen, Wirtschaft schrumpft – wird Deutschland immer ärmer?)

Of course it is true that Germany is now in a very mild technical recession. It is also true that many people have seen their real income squeezed by inflation. But there are also substantial winners, notably in the corporate sector. In overall terms an inflation does not make a country poorer. It redistributes between groups. The only way an inflation makes an entire society poorer is if it is driven by a terms of trade shock. That is exactly what Germany, along with the rest of Europe has suffered since 2021. But the terms of trade shock amounts according to the ECB to a one-off loss of 2 percent of GDP, a modest setback, not an enduring trend towards immiseration.

What with the war in Ukraine, the technical recession, stubborn core inflation, the legacy of underinvestment, the politics of the energy transition and the threat of Chinese competition in core areas of industry, like motor vehicles, German policy-makers certainly have their plates full. It would not be surprising, if growth turned out to be disappointing. But I’m not aware of any serious medium-term forecast that sees Germany sliding into a position of stagnation or per capita decline - immiseration/Verarmung - as suffered for instance by the Uk or Italy. So what is going on?

On the panel I had the impression that a societal panic around growth, diminished expectations etc was being instrumentalized for conservative rhetorical purposes. Essentially, a diagnosis of a general German crisis was being turned into a stick with which to belabor the Scholz coalition. Regrettably, both liberal Finance Minister Christian Lindner and Robert Habeck of the Greens at the Ministry for Economy and Climate have chosen directly to address the issue of national prosperity, warning that it was bound to suffer and that it needed redefining. This frankly feels like an exaggerated response to what are relatively modest negative trends. If Germany had put in place more effective social protections to cushion the worst off more promptly, there would be little reason to be concerned about growth as such. The worst of the terms of trade shock will be transient.

To try to counter this lurch into omni-pessimism, I wrapped up my contribution to the Illner show by arguing that we should separate out the different dimensions of concern - the cost of living crisis, the recession, China etc - to address them separately with well-targeted policy.

***

Watching this phantom menace of German decline being conjured out of the fog, left me mulling the politics of polycrisis: If we agree that there is a lot going on, that we are in midst of the fog of war, if our reality is defined by the convergence of forces, how do we define it and respond to this condition. What are the politics of declaring a multiple, overdetermined crisis?

I began thinking about this back in 2021 when we had the climate Kalecki moment. Encountering German declinism has me returning to the theme.

I think some of the critics of the idea of polycrisis are skeptical precisely because they fear something like what I was sensing on the panel - a conflation of quite distinct problems under the sign of a general pessimism. Often this can be scaremongering or, tacitly, a call to cynical acceptance - a shoulder-shrugging S.N.A.F.U.

Talking about inflation in Germany has certainly sensitized me to this risk. But clearly that is not a good reason for giving up the concept of polycrisis as such. It is a reminder that we need to be selective and strategic in the claims we make to crisis. It is an argument for being very precise about the distinct challenges that we are worried about and the linkages between them. I.e. it is about taking the “poly” in polycrisis seriously and not conflating a variety of very different forces into a single “general” crisis. This is not to deny that in certain situations a “fusion” of crises can occur. But we should be careful in invoking such a fusion and critical of “general crisis” discourse especially when it comes from an avowedly conservative side. The good news is that whatever the dynamic of the broader global polycrisis, as tough as the last three years have been, as difficult as are the politics of a three-way coalition, the Federal Republic of Germany is by any reasonable standard a very long way away from disaster.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week