“How do we avoid the pitfalls of appeasement?”

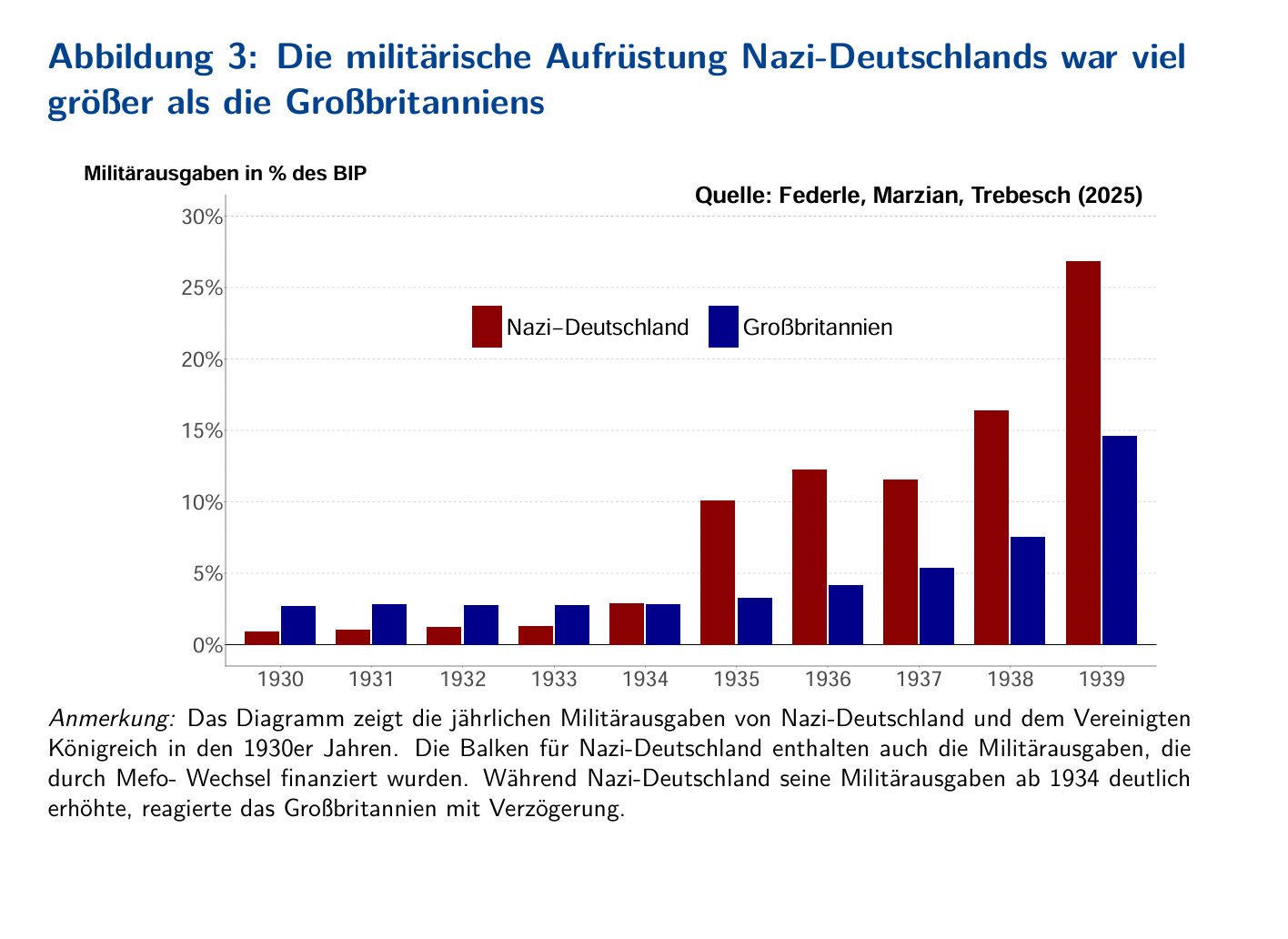

“How do we avoid the fate of democratic Britain, outspent by Nazi Germany in the 1930s"?”

(Title: The rearmament of Nazi Germany was far larger than that of Great Britain)

Source: Marzian & Trebesch 2025

“How should Europe prepare for the new war economy?”

“Do we really want Germany to rearm? Remember the last time!”

Several moments in conversations over the last few weeks have brought me up short and made me want to reach for history, not as a source of timeless verities, or recurring analogies, but to provide context and to explain how we got here.

Faced with our current unsettlement and disorientation, the historical experiences of the mid 20th century, conjured up by references to “war economies” and Nazi aggression, serve as points of historico-intellectual reference that, in their weight and drama, “meet the moment”. But at the same time comfort us in their familiarity. Because they are “known”, they are meant to illuminate the fog we are in.

But what if they are, in fact, fata morgana, dark mirages of the past that confuse rather than enlightening the discussion.

The first thing is to start with a reality check on talk about “war economies” and the lessons to be learned from the 1930s.

What is a war economy?

In the most extreme case - as, most recently, during the Syrian civil war - a war economy is one in which the war becomes the economy and the economy becomes war. All boundary lines dissolve and military violence is used for immediate self-enrichment by war lords, whose activities dictate all other forms of production and distribution.

Under more settled circumstances, as in the “classic” war economies of World War I or World War II, some semblance of a division between the military and the civilian life, the political and the economic spheres is preserved. In this case, war economies refer not to the dissolving of the peacetime economy into war, but the mobilization of that economy for a gigantic war effort. Economists prepare plans. Macroeconomics acquires a new and historic importance. Production is diverted. Women workers are substituted for men who are drafted into the military. Trade and consumption are curtailed. Markets are replaced by rationing etc.

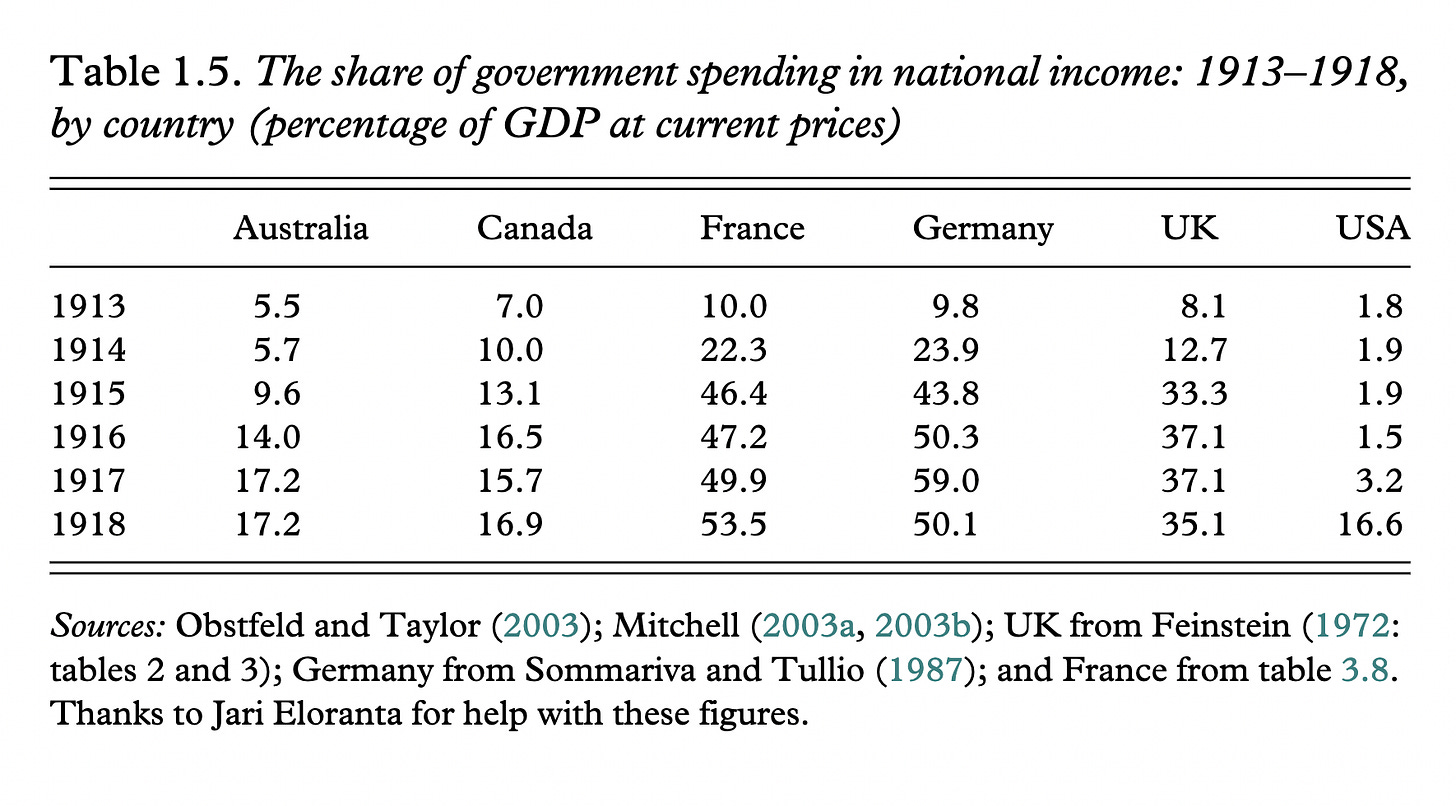

Already during World War I, as far as statistics allow us to measure, it was “normal” for combatants to mobilize 30-40 percent of output, for purposes of the war. Military spending is proxied in the table below by the increase in government spending as a share of GDP between 1913 and 1918.

Source: Harrison and Broadberry 2005

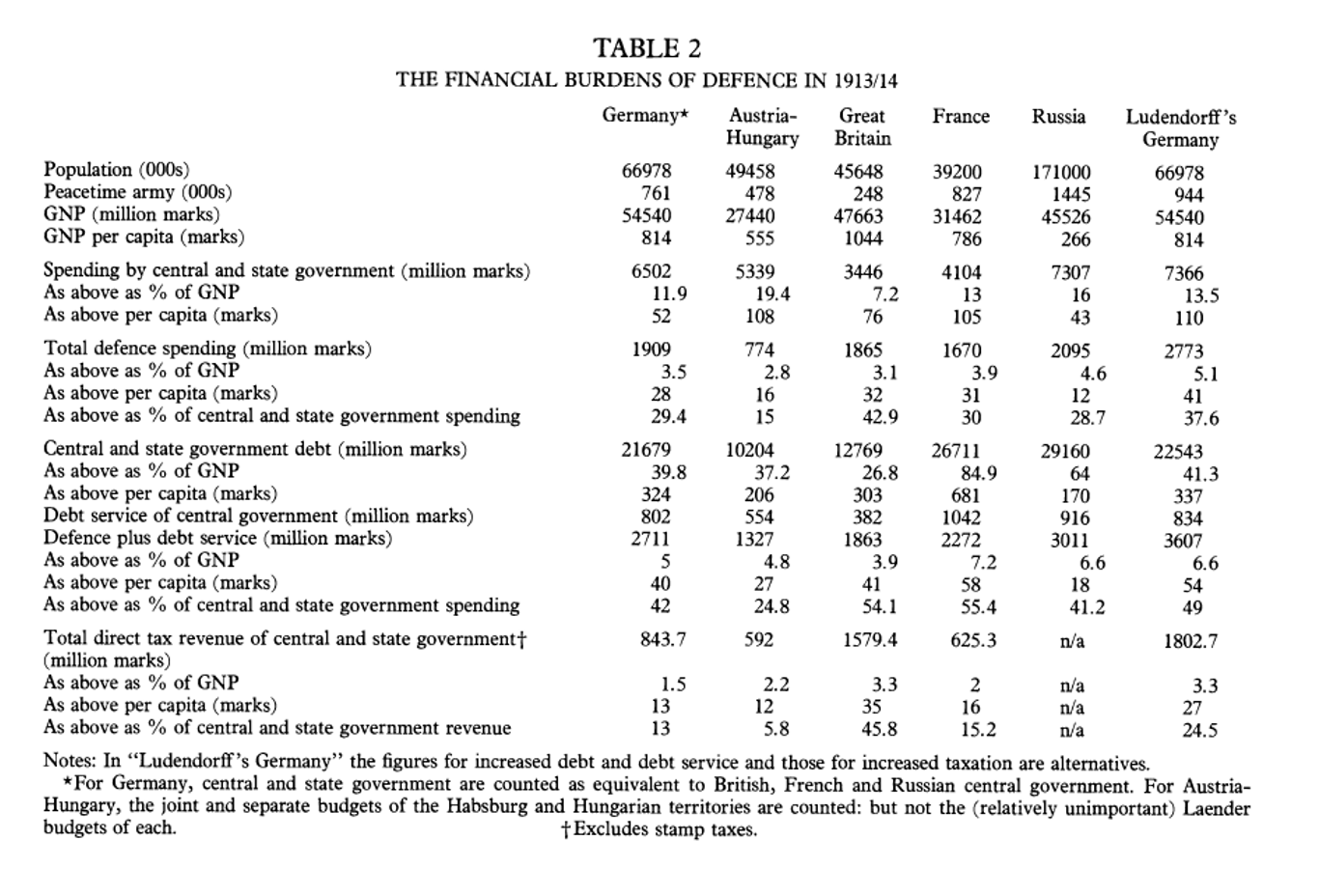

In 1914-1918 this level of mobilization came as a devastating shock. Before 1914, major powers maintained large and competent military establishments. They built fleets of battleships and maintained hundreds of thousands of men under arms. But in this heyday of classic militarism, they rarely spent more than 3-5 percentage points of gdp on the military. In proportional terms their spending was comparable with that of NATO members in the 1970s and 1980s. In absolute terms, because these were economies operating at lower middle income levels in modern terms, their spending was far lower than later in the 20th century.

Before 1914, dark prophets already imagined total war, but official planning proceeded on the basis that war would be short and would be decided on the battlefield. It was not until the autumn of 1914 that the horrifying reality of a protracted total war sank in. By 1916, in the battles of material (Materialschlachten) at Verdun and on the Somme, material and human attrition became the dominant military principle.

For many combatants - the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany and Russia - the disintegration of the home front under the weight of economic and social pressures and the material exhaustion of the military itself would put an end to the war amongst revolutionary collapse.

The lesson was not lost on contemporaries. After World War I, the incumbent liberal powers led by the British Empire and the USA pushed for land disarmament combined with a monopoly of strategic naval power. That combination, they hoped, would secure their global hegemony at an affordable price, without the effort of more radical mobilization.

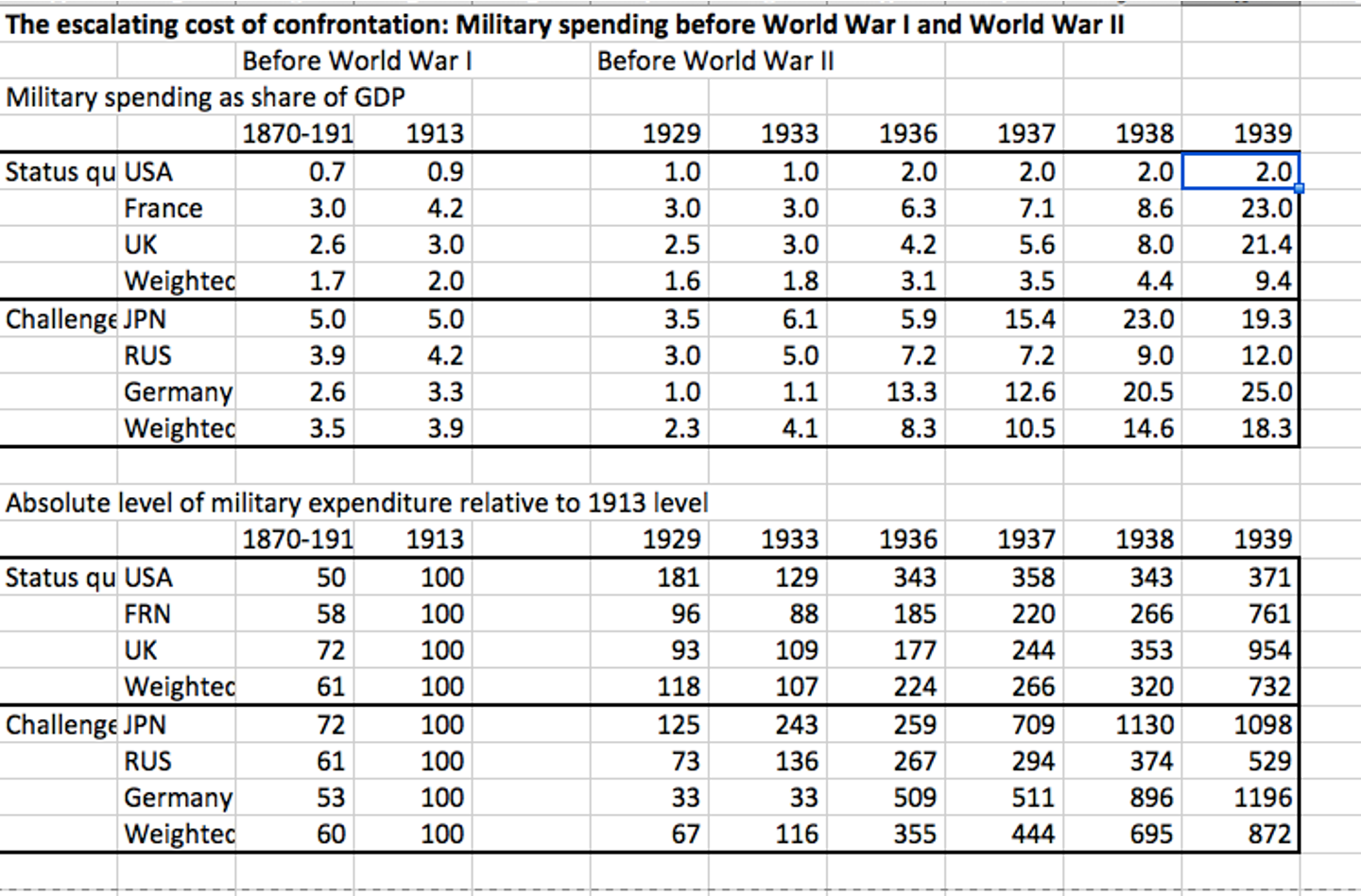

The challenger powers led by the Soviet Union and then fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan envisioned their politics, by contrast, as projects of total mobilization. Interwar German military theorists borrowed from the Soviet Union the idea of a Wehrstaat (Defense state). Once rearmament began in earnest in the early 1930s they made those visions real. Spending in “peacetime” surged to levels never before seen. It was not a bug but a feature of British appeasement strategy that they were slow to respond. They staked their own long-term strategy on economic balance and on long-range high-tech strategic forces, at sea and in the air.

Tooze Deluge 2014.

Ultimately, the British strategy would prevail, if only in combination with the United States and the Soviet Union. But even if it ensured that Britain was on the winning side, as a strategy of deterrence it failed. Progressively from 1936 to 1939 deterrence broke down and the world was launched into a conflict with levels of mobilization even greater than those in World War I. The Soviet Union, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan operated inhuman regimes of total mobilization.

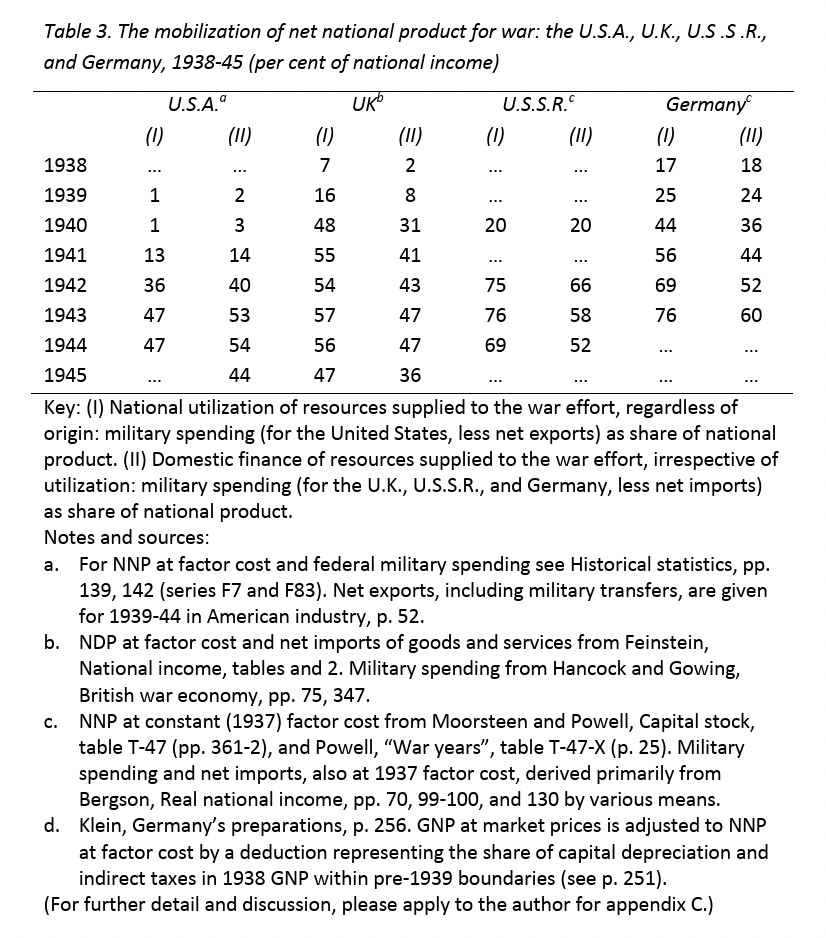

Mark Harrison compiled one of the standard references sources for economic mobilization in World War II. His figures make for impressive reading.

It should be jarring, to say the least, to see Nazi rearmament and the era of “war economies” invoked as a common sense reference points for Europe’s defense policy today.

In fact, nothing like the mobilization of the 1930s and 1940s is being contemplated even by the boldest European military planners. For very good reason it is not Nazi rearmament but British appeasement era levels of spending that offer a sensible reference point for Europe today. Nazi rearmament spending was unbalanced, helter skelter, lacked strategic direction and stirred the German military leadership to the edge of mutiny. Quite sensibly, in 2025, Germany’s parties are haggling over a budget that might raise defense spending to 3 of 4 percent of GDP, not to 30 or 40 percent. To refer to this as “war economics” is to muddy the waters.

Unless the DOGE team pushes through really swinging cuts to the Pentagon budget, the envisioned level of spending on the Bundeswehr would be little more than the routine US defense budget, in proportional terms.

Furthermore, if Russia is the main antagonist, these are perfectly sensible proportions.

Though Moscow is fighting a major war against Ukraine, it is doing so with military spending running at far less than 10 percent of gdp, at least as reported by official data. This is far below “war economy” levels. Russia’s economy though it has capabilities in key industries and lots of oil and gas, is tiny by comparison with the economy of the EU. In due course a far smaller European effort will be necessary to match Russia’s forces. Europe has key technological deficits and has much to learn from Ukraine’s battlefield experience, but this requires not a massive, all-embracing “war economy”, but smart industrial policy and urgent lesson-learning from Ukraine’s battle-hardened soldiers.

Germany must make a contribution to Europe’s defense that is commensurate with its size and wealth. That will mean that Germany makes the largest contribution, not in per capita terms, but in overall heft. This does not mean that Germany will dominate. It is not that much larger than its neighbors and it is significantly more reluctant to commit to defense than the Poles, who are aiming for defense spending of 5 percent of GDP. France, Italy and Spain will also make significant contributions. East European manpower and industrial capacity may also play a key role.

Does Germany’s rearmament pose a fundamental challenge to the European balance of power? It is certainly a change. But we should remind ourselves what the success story of the postwar period was built on.

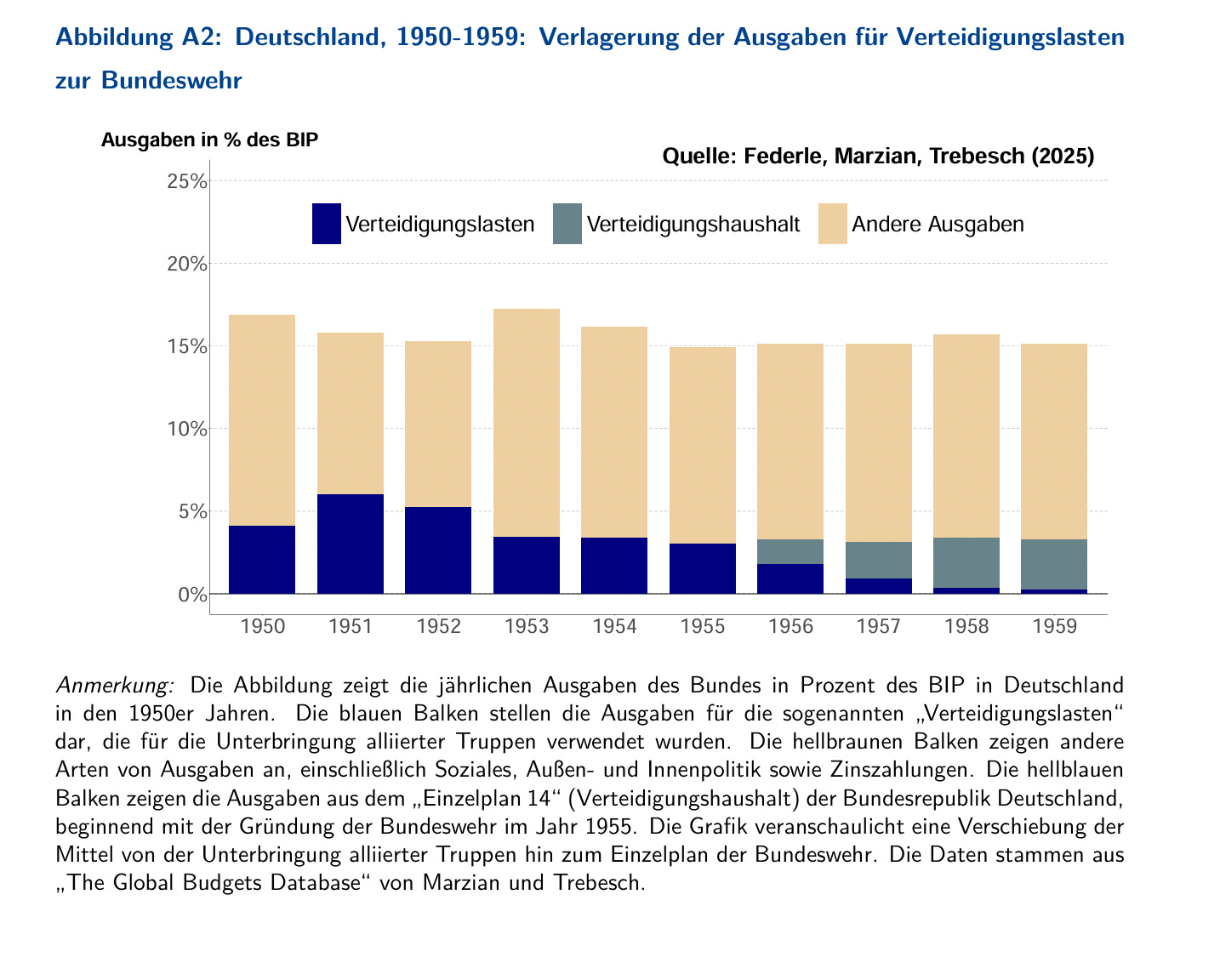

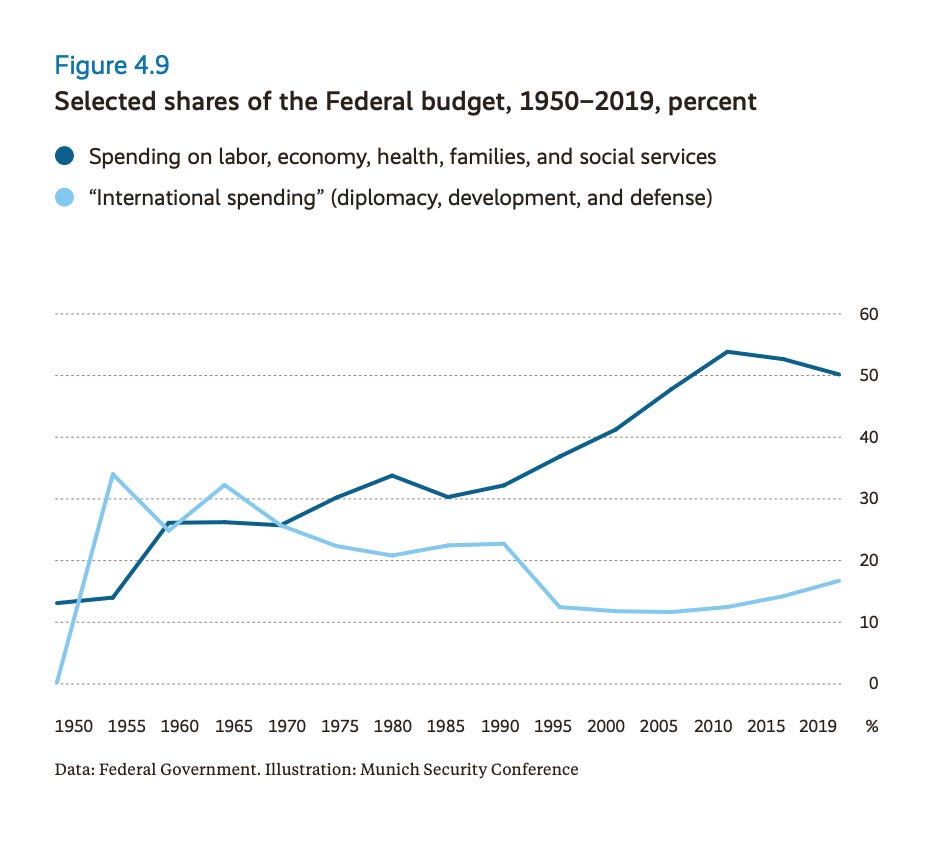

It is a myth that the Federal Republic (or the GDR) was ever disarmed or free from the costs of defense. The closest it has ever come is since the 2000s.

Source: Marzian & Trebesch 2025

In the early days after World War II, both Germanies made a large contribution to their defense costs. Initially, this took the form of budgetary payments for occupation costs. Then they built their own militaries. In doing so they used the equipment of their patrons - the US and the Soviet Union - but they also connected directly to Germany’s military history. In terms of scale, the overall military structure of the Federal Republic was reminiscent of that of Imperial Germany (Kaiserreich).

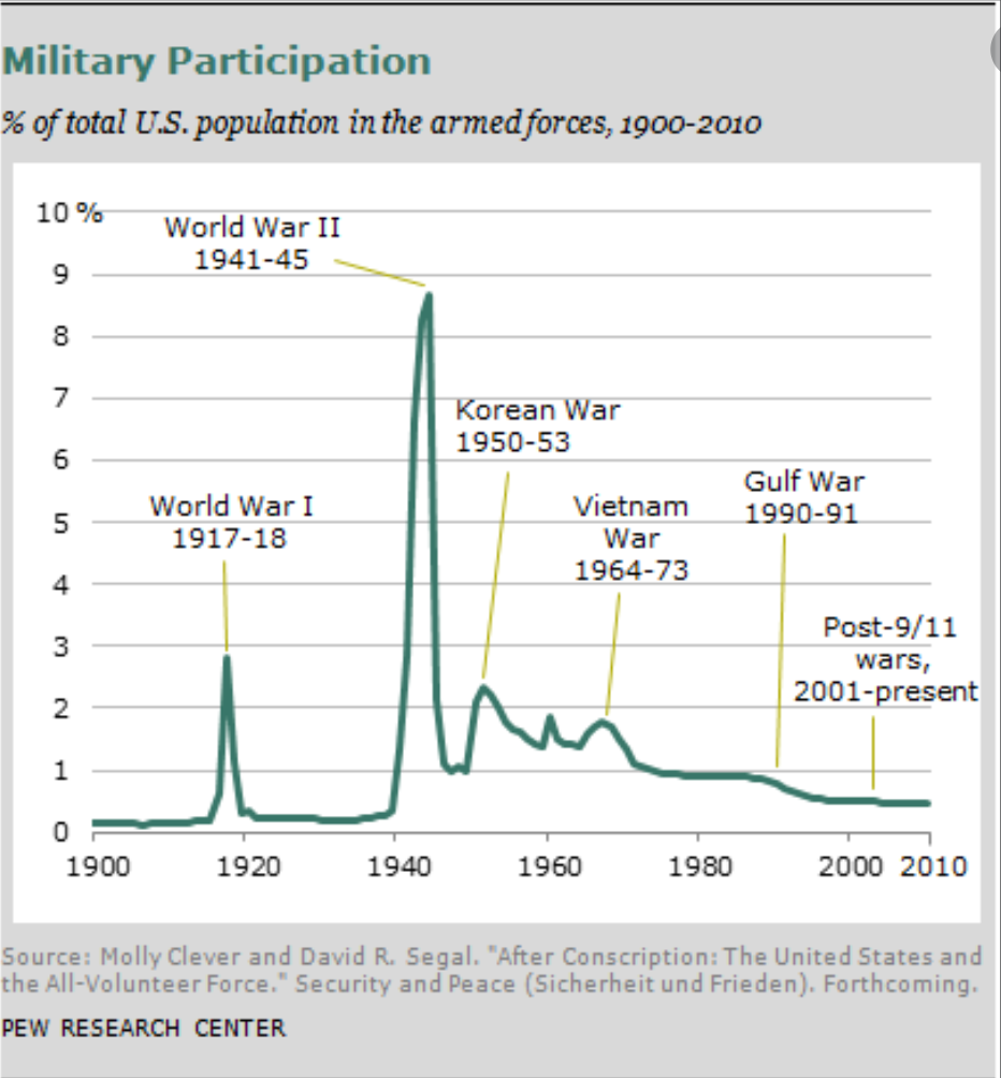

West Germany was a “normal” European military power with a large standing army based on a period of universal conscription followed by reserve duty. Through the 1980s it was unusual for young men to choose conscientious objection. Common place militarism was still very much the norm.

In the 1980s the Bundeswehr fielded a force of 500,000 soldiers, with a war-strength based on a reserve call up of 1.3 million men. At the organizational level, the Bundeswehr’s armored and mechanized formations followed the Wehrmacht model. The main force was organized into 3 corps of 12 powerful divisions with 36 brigades and just shy of 3000 first class main battle tanks.

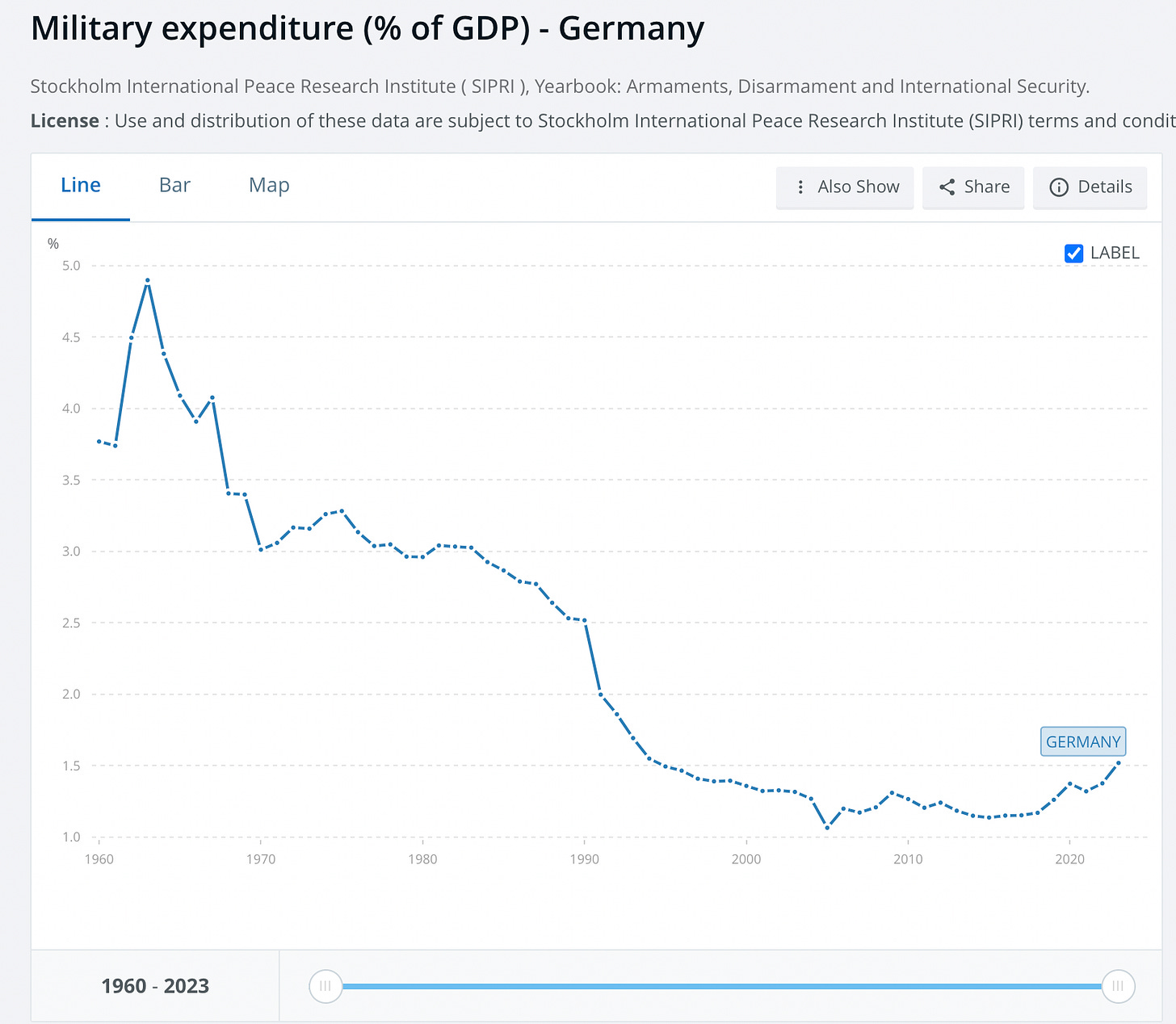

In terms of the economic load the figures are similarly “normal”. Defense spending in West Germany peaked in the early 1960s just short of 5 percent. It then plateaued at 3 percent of GDP throughout the 1970s and 1980s. All of these are figures that would have been unsurprising in Imperial Germany. Far from being demilitarized, West Germany was a normal power state, contained with the powerful NATO alliance system. What it was not, was the total mobilization of the Nazi era. But that was the exception not the norm of modern militarism.

Nor was this model confined to Germany. In the era of Cold War conscription in the US, the share of the population in uniform was slightly greater than that of Prussia prior to 1914. West Germany continued that tradition and pulled its weight.

Military power was at the heart of statehood in the “postwar” era. As David Edgerton has pointed out, it was not until the 1960s or later than welfare dominated warfare in modern states. This held true for West Germany as well. As a share of the German state budget, it was not until the 1970s that “social costs” outclassed “external functions” of state power and national security.

In the 1908s, the Bundeswehr was the largest military in Europe and was generally thought to be highly competent, but this was not seen as a threat to the European order but a vital contribution to NATO. It helped, of course, that the US was powerfully committed to NATO and the British, French and Americans all had troops stationed in Germany.

When the Cold War ended, contrary to fears expressed at the time, Germany did not exploit the situation to establish European dominance Instead, it took the peace dividend. But the important point to make is that demilitarization and utter dependence on the US did not define the Federal Republic’s security policy from the start. It is a relatively recent development.

Current estimates put the entire force necessary to replace the US contingent in Europe at 330,000 troops or 55 brigades. That will be a stretch. At present Germany can barely muster a single combat-ready division. But getting to a place in which large European states are able to competently defend themselves does not require unleashing the demons of World War II. It requires returning to something more like the normality of Europe in the age of NATO deterrence in the 1970s and 1980s.

This is not to underestimate the change or the challenge. The realities of the late Cold War were not comfortable. Anyone of a certain age will remember the nightmarish shadow of nuclear fear and scenarios of World War 3. In the late 1980s Gorbachev and the end of the nuclear stand-off came as a huge relief. But what preceded it was not “war economy” or a state of “emergency” - at least not unless you shared the diagnosis of the far left and the peace movement. The late Cold War was simply the normality of a conflicted and riven world bequeathed to us by the “age of extremes” (Hobsbawm).

The world of polycrisis in which we find ourselves, faces Europe with new security challenges. But it will not help if we compound our anxiety by overlaying present day reality with half-remembered ghosts and visions from an era whose history of military violence was even darker than our own.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

"spending on the Bundeswehr would be little more than the routine US defense budget, in proportional terms" that would make how many military bases? 20?40?80?

A great piece with a shrewd conclusion, but I’d say that total war was not only envisioned before 1914 - it was seriously prefigured in the US Civil War.