The concept of genocide always included cultural genocide.

This is not surprising. The term genocide was coined by Raphael Lemkin to characterize the Nazi assault on Eastern Europe and on Poland in particular. The murder campaign against Poland’s Jews was the leading edge of a more comprehensive plan. Eventually the technocrats of the Third Reich foresaw the destruction of Polish nationhood per se, the physical extermination of a large part of the population and the enslavement of the rest. You can’t do that without cultural erasure, without putting an end to teaching, learning, research and cultural memorialization. For that reason upholding education and learning were vital tasks both of the Jewish and non-Jewish resistance in Poland.

Cultural genocide can take place in any context. All human societies have cultures.

Campaigns of destruction targeting institutions of learning and teaching have more specific historical conditions. They depends on the development and differentiation of those institutions. Julius Caesar took risks with the library of Alexandria. In the schoolbook version of European history the overrunning of the Roman Empire resulted in the collapse of literacy, which was rescued only by the activity of monasteries. The regime of chattel slavery was upheld by the suppression of literacy amongst the enslaved. Imperial cultural policy routinely represses native languages, silences music and theatre, censors literature and persecutes teachers and students who persist in upholding their culture.

The term scholasticide was first used by Oxford academic Karma Nabulsi in 2009 to characterize Israeli attacks on the educational infrastructure of Gaza. But it is clearly a term that applies in many settler-colonial settings, to genocides and in prolonged insurgency and counter-insurgency struggles.

Genocide and scholasticide may go hand in hand as interlocking parts of a comprehensive “final solution”. In some cases scholasticide is simply part and parcel of a general program of annihilation. You kill teachers and students along with everyone else. In other cases scholasticide may take priority. The killing of teachers and students and the destruction of educational and cultural institutions constitutes a project in its own right.

Scholasticide can take many forms. It may be centrally directed and highly targeted, as in the rounding up and execution of 25 Polish academics by the Nazi authorities and their Ukrainian helpers in Lviv in July 1941. But it can also be driven by genocidal energies “from below”. Killing and destruction on a large scale are social processes. They involve more than an order from above. The politics of the individual génocidaires, small unit social pressures and personal resentments provide the energies that “get the job done”. This should not be dismissed as unauthorized “freelancing”. Overall organizational success depends on individual local initiative and self-motivated actions. Decentralized action is not a bug, but a feature. The enemy’s cultural institutions, teachers and students make suitable symbolic targets.

Cultural genocide can also be viewed in economic terms. Scholasticide involves the selective elimination of the mechanisms through which a society maintains and multiplies its “human capital”. In this way scholasticide serves a strategic, long-term purpose. The imperial masters fantasize about subordinating “helot” nations. But laying waste to cultural institutions also has a more immediate impact. Modern “place-based” economics allows us to quantify the role played by Universities and Colleges as “anchor institutions”. Positive economic policy aims to reinforce and multiply such regional hubs. If on the other hand your aim is to “unmake a place”, the lesson is no less obvious: remove its anchors.

Universities and schools are not just economic and social spaces. They have a physical presence. They often boast prominent buildings and big halls. Many maintain sprawling campuses. Those can become the stage for mass politics, for demonstrations, for occupations, but also for sieges and open combat. They serve well as make-shift military bases.

Particularly in poor societies and poor communities, whether in Sudan or an American inner city, places of learning are often places of relative wealth and technological sophistication. There are computers in Universities and schools, which make attractive targets for theft and looting. Fragile cultural artifact like school records, books, archives, museums etc are both easy and satisfying to destroy.

So, apart from deliberate acts of scholasticide it is common place to see campuses, universities and schools become targets both for organized violence and disorganized looting. How to interpret the type of violence directed at Universities and schools will depend on the particular battlefield and the particular conflict.

In the civil war raging in Sudan, to focus on one of the largest conflicts ongoing at the present time, the education system is suffering spectacular damage.

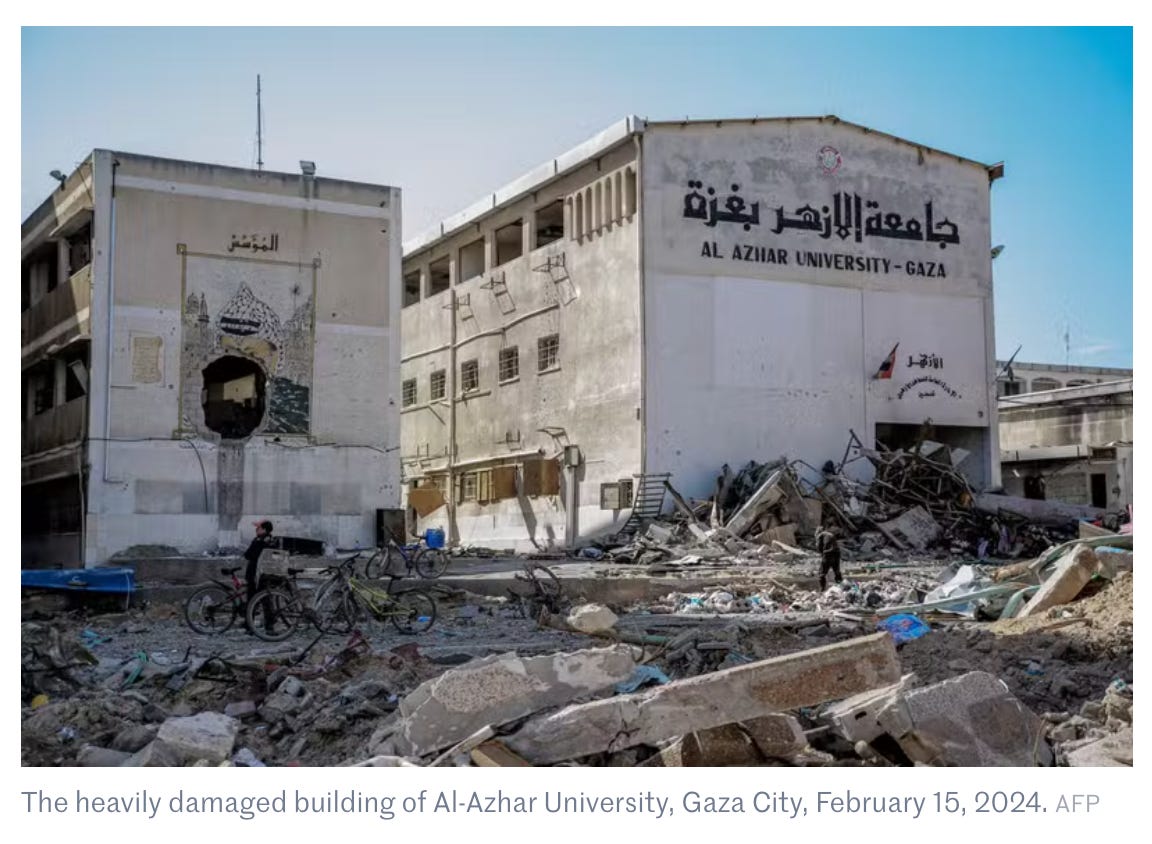

In the last thirty years the universities and colleges of Sudan have undergone dramatic expansion to accommodate the talents and aspirations of a population that has almost doubled in size in the last generation. Overall Student numbers have increased tenfold since 1980 with female students now accounting for more than half of those enrolled. According to one source, Sudan before the current conflict was “home to more than 70 medical schools with an annual intake of more than 5,000 students, representing 23% of medical schools in Sub-Saharan Africa.”

Source: Beshir, M. M., N. E. Ahmed, and M. E. Mohamed. "Higher Education and Scientific Research in Sudan: Current status and future direction." African Journal of Rural Development 5.1 (2020): 115-146.

The impact of the war that broke out between the Sudanese army and the RSF in April 2023 has been devastating. According to one report:

Given that more than 10.4 million Sudanese were forcibly displaced, among them scientists, the educational system has been hampered. Available data indicate that in Khartoum State (both the political and educational center of Sudan), 39% of governmental and 73% of non-governmental universities were occupied by RSF (the rebel militia), whereas it was 10% of governmental and 8% of non-governmental universities in Gezira state. This contrasts with 3% of governmental and 5% of nongovernmental university in South Darfur. Some universities and colleges were partially or completely damaged, while in some it was not possible to determine the damage. This has led to complete shutdown of the universities, forcing students to find expensive alternative ways to continue their education or abandon it altogether. Scientists and science in Sudan faced many challenges, which are difficult to overcome.

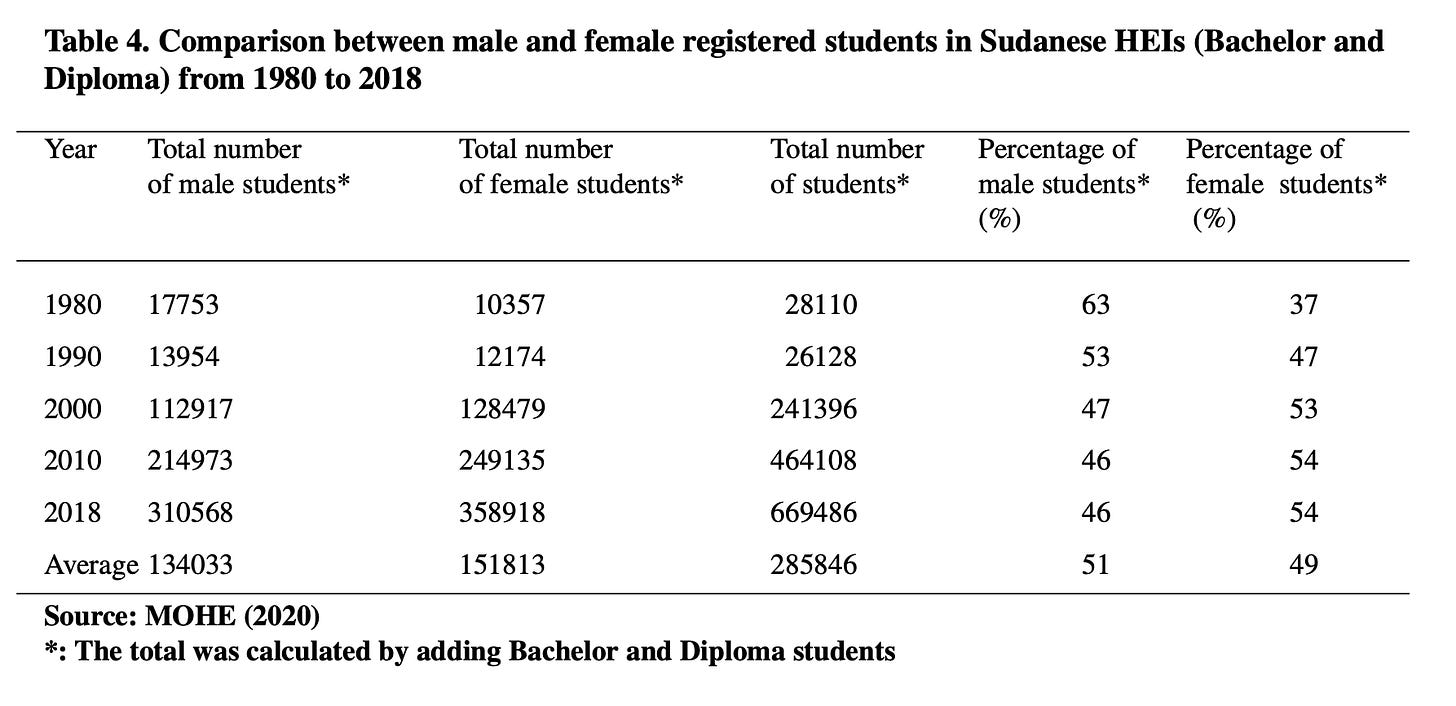

As of September 2024 the situation of major institutions in Sudan was as follows:

Alamin, N. K., Idris, A. A., Khugali, E. E. A., KALCON, G. O., & SS, M. (2024). Science in times of war: reflections from Sudan. ASFI Research Journal, 1(1), e13267.

In these occupations and disruptions of higher education in Sudan there is an element of chaos and low-level vandalism. But there can be little doubt that this is more than just wanton destruction. The RSF’s track record of genocide against the population of Darfur and other regions is well established. Their methods range from mass murder, to forced conscription and mass rape. Given this general propensity for genocide, it would require further evidence to establish what particular role the attack on universities plays in RSF's campaign.

As one report explains, Sudanese University administrators, staff and students have responded creatively to the challenge:

Since 2019, Sudanese universities have experienced academic anarchy due to political instability and COVID-19 outbreak. Nonetheless, this situation encouraged universities to introduce e-learning systems. Subsequently, when the war started, universities already had some expertise in the field and most of the universities established e-learning platforms. In the reality of the war, the universities’ administrations are now focusing on the continuation of under-graduate programs through the established elearning. The universities managed to introduce solutions to some of the challenges and many universities started their academics programs online, in safe states or abroad. Some Sudanese universities have already relocated some of their classes (specifically, senior medical students) to other countries, a very expensive alternative. Moreover, many universities developed Memorandum of Understanding with sister universities in safer states. Such initiatives have facilitated many universities to accomplish the practical parts of their curricula. Furthermore, some Sudanese universities even established branches abroad.

But there can be no doubt that the damage in terms of destruction, lost research, interrupted education and trauma will be deep and lasting.

One painstaking survey-based study conducted amongst Sudanese students and faculty iby Husam Eldin E. Abugabr Elhag and Rania M.H. Baleela found:

38 % of the students were displaced with or without their families in Sudan and 32 % sought refuge in other countries. Those who sought refuge (32 %) mentioned six countries for refuge with the majority in Egypt (16 %) while others crossed borders to other countries such as South Sudan, Libya, and Uganda. In contrast, others travelled to Saudi Arabia and Northern Ireland. When asking the students to clarify their academic situation and method of studying, it was found that the biggest portion 35.14 % of students are still enrolled and depending on PDF format or audio recordings and they communicate with their educators using WhatsApp or Telegram apps, 21.62 % of students were enrolled but the academic year was suspended, there was 18.92 % who sought refuge, and couldn’t continue their studies, students in safe zones 8.11 % were still attending at their universities, while other groups withdrew from studying, enrolled in university hubs outside Sudan, either with their same university or were transferred to another university. The data also revealed that 35 % of the students were not living with their families, however, the majority of students (62 %) were forced to work, either displaced in Sudan (27 %) or outside Sudan (27 %). The percentage of students who were not forced to work reached 38 %, with the majority of 22 % not displaced.

The violence unfolding in Sudan should receive far more attention that it does. It is part of a wider regional polycrisis that is vastly underweighted in the global economy of public attention.

But, as dramatic as it is, looking more closely at what is happening to the education system in Sudan allows us to highlight what is truly unique about the campaign of destruction waged by the Israeli military in Gaza since October 2023.

What sets Israel’s campaign against Gaza apart, is, quite simply, its radical intensity.

Before the onslaught, Gaza was a compact space with clusters of dense urban settlement. It is comparable in population and size not to Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, but to neighboring Omdurman, Sudan’s second metro area. Omdurman has a population of 2.3 million spread over 230 square miles. In Gaza 2.1 million people live in 139 square miles.

Into the most densely populated parts of Gaza’s urban areas, the Israeli military have unleashed extraordinary firepower. Already in December 2023 John Paul Rathbone the FT’s defense and security correspondent concluded that Israel was inflicting on Gaza one of the heaviest and most concentrated bombardments in military history. By April 2024 Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor put the figure for munitions used at 70,000 tons of explosives. For sake of comparison that is ten times greater than the tonnage dropped in the notorious bombing raid on the German city of Dresden in February 1945. It is four and half times the explosive force of the atomic bomb that annihilated Hiroshima in August 1945. In November 2024 the Environmental Quality Authority of the Palestinian Authority estimated that in barely more than a year, the Israeli bombardment of Gaza had delivered no less than 85,000 tonnes of explosives.

The result in Gaza is destruction of an intensity rarely seen in the history of warfare. It is unimaginable in Sudan’s civil war, which is fought with far less military equipment. Nowhere in Sudan has suffered anything like the concentrated destruction meted out to Gaza. What has enabled this concentration of firepower are not only Israel’s own resources but unstinting US aid. Enthusiastically promoted by the Biden administration and supported by huge majorities in Congress, this has accounted for a very high share of the munitions dropped.

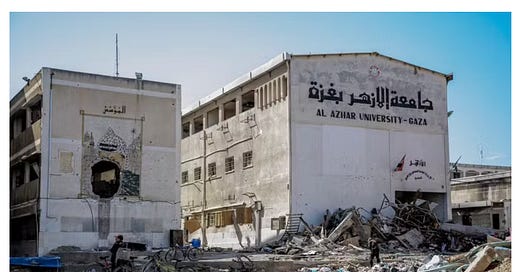

Across Gaza more than half of all buildings have been damaged. In Gaza city the share is over 80 percent. Unsurprisingly, the havoc extends to Gaza’s 12 universities all of which have been completely or partially destroyed. At the same time, the intensity of fire and the orders of the IDF have brutally displaced virtually the entire population making it impossible for normal life to continue. If education and scholarship have continued - and they have - it is only due to the dauntless determination and bravery of Palestinian faculty and students. Not only is the damage to the education system clearly far more comprehensive than that suffered in Sudan, or anywhere else in the world, but the kind of communications networks that allow educational researchers to assess the scale of the damage in Sudan in relatively precise terms, no longer exist in Gaza. It is a scene of total ruination.

There is evidence for specific targeting of Gaza’s educational institutions and their staff. Human rights monitor Euro-Med, a Geneva-based independent nonprofit, reported as long ago as last January that the Israeli army was targeting academic, scientific and intellectual figures, bombing their homes without prior notice. By that point over 95 academics have been killed, alongside hundreds of teachers and thousands of students.

The demolition of Universities has been systematic and, on a number of occasions, gleefully documented by the perpetrators. As in other cases of scholasticide, this is not just frenzied looting or vandalism in the heat of conflict; we can see pleasure taken in the burning of the enemy's books and libraries, because the political, cultural value is recognized. In one social media clip, an IDFsoldier standing in the rubble of al-Azhar University says, “To those who say why there is no education in Gaza, we bombed them... Oh, too bad, you’ll not be engineers anymore.” Israeli forces used over 300 mines to destroy the huge al-Israa University, near Gaza City, last January, having first used the building as a military base in the war’s first months.

Dr. Ahmed Alhussaina, the vice president of al-Israa University, has drawn attention in interviews to the decimation of artefacts and archives:

We had a museum that [housed pieces] from a lot of collectors and regular people around Gaza. We had 3,000 artifacts in it, and we were going to open it to the public, we were just about to finish the building.

The small building next to the main campus building also was destroyed and looted. All that was gone, over 3,000 artifacts from the pre-Islamic [period], from the Roman Empire, from all the history of Palestine. We had all the currencies from the state of Palestine, 1905, 1920s, all these times. Like I said, we have ancient, we have recent modern history, and that’s all gone. Nothing is there. They looted it before they destroyed it, and then they just booby trapped the building…Propaganda says people with no land came to a land with no people. I mean, they’re saying the Palestinians had no people, there was no such thing as Palestine, and this thing defies it, and I think that’s one of the main reason they attack these kind of things. They uproot trees. They uproot, even, cemeteries. They uproot churches; the third-oldest church in Palestine was bombed. So many mosques, hundreds of mosques, hundreds of schools. Every single university was hit somehow. Some of them partially damaged, some of them totally destroyed. Schools are all mostly gone. Mosques, hospitals, medical centers. Even, like I said, libraries, the oldest library — Gaza City Library — also was destroyed. I don’t know, what else can you explain [about] this? It is what it is. It is a destruction of everything Palestinian. They want to make Gaza unlivable and they want to destroy its history.

Folks outside the conflict who have professional attachments to Universities and education have every reason to be horrified and to protest.

The “Resolution to Oppose Scholasticide in Gaza” presented at the annual conference of the American Historical Association (AHA) was approved earlier this month by an overwhelming majority – 428 to 88 members in attendance. Drafted by Historians for Peace and Democracy, representing over 2,000 AHA members, the resolution noted, citing UN reports, the IDF’s obliteration of 80 percent of Gaza’s schools, all 12 of its universities, and the destruction of “archives, libraries, cultural centers, museums, and bookstores, including 195 heritage sites, 227 mosques, three churches, and the al-Aqsa University library, which preserved crucial documents and other materials related to the history and culture of Gaza.”

Given this undeniable state of affairs, it is shameful that the AHA leadership moved to veto the scholasticide resolution. The claim from AHA leadership that the issue “lies outside the scope of the association’s mission and purpose” sits at odds with the organization’s prior positioning. As Middle East Monitor reports:

Mary Nolan, professor emerita of history at New York University and a member of the steering committee that proposed the resolution, pointed to the AHA’s 2007 condemnation of the Iraq War and its recent critique of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “The Council’s actions are undemocratic and suggest a ‘Palestine exception’ to free speech,” Nolan told Haaretz. Christy Thornton, associate professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, described the veto as “not just disappointing but incredibly short-sighted.” She warned the decision could alienate members and weaken the organisation. “The decision to not even let the entire membership vote will alienate generations of historians from the organisation at a time when the defence of the profession needs more energy, not less,” Thornton said, adding that she would not be surprised if “hundreds of historians refuse to renew their memberships.”

I am not an AHA member, and it is long past the time we should be expecting consistency, intellectual honesty, or anything close to bravery from the leadership of American establishments when it comes to protesting the destruction of Palestinian life. The AHA leadership’s decision confirms that depressing conclusion.

Plainly, the destruction of historical materials and the reduction of Gaza’s educational institutions to rubble, should be of concern not just to the profession of history but to scholars in general around the world. But in Gaza scholasticide does not stand alone. In this case destroying Universities is not the thin end of the wedge that is yet to come. Israel is not perpetrating a cultural genocide in preparation for something else to follow. A scholasticide has taken place as part of the wholesale erasure of all forms of regular Palestinian life in the Gaza strip. As important as it is to identify particular institutions and particular victims, it is the extreme intensity and generality of the Israeli assault on Gaza that stands out as well as the generous support given to that campaign of destruction by the richest and most powerful nation on earth, the United States.

I wish to thank my dear friend and comrade Natasha Lennard for inspiring me and helping me to write this piece.

Thank you! A moving condemnation of scholasticide as a crime against humanity.

Can't thank you enough for this article. Scholasticide deprives future generations of their culture, and sense of who they are. But that was the objective in Gaza.