Look around the troubled world and ask yourself the questions: What am I missing? Where are my blindspots?

If you start with the Global Humanitarian Overview for 2024, the answer, for most of us, is not hard to find. The on-going humanitarian crises in Afghanistan, Syria and Myanmar are huge. Central America and Haiti should garner far more attention. But by far the largest and most underreported region of crises is the belt that stretches from the Democratic Republic of Congo, to the North East by way of Burundi, Chad, Sudan and South Sudan, into Northern Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia and across the Red Sea to Yemen.

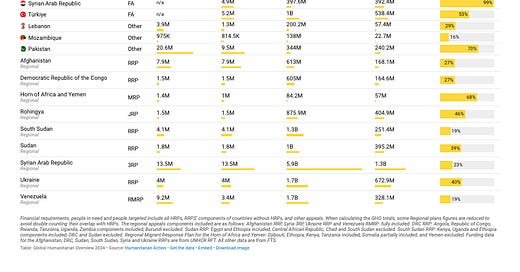

At the end of 2023, around 110 million people were thought to be in need of humanitarian assistance across this mega-region. If you include the Democratic Republic of Congo, which adjoins East Africa, the total of people in need comes to 136 million, or 37 percent of all the people in the world in need of humanitarian relief.

To use humanitarian statistics of need as our metric, flattens a hugely complex and diverse human experience. It risks reducing Africa to a panorama of disaster. But by the same token if we don’t address these numbers we don’t do justice to the huge scale and multiplicity of crises impacting the region and its people.

Of course, to speak of a single region is to risk over-aggregation and to underplay stark differences. There are deep historical faultlines that divide the region - between Arab and Africa, Christian and Muslim and between different ethnic groups.

As Nosmot Gbadamosi points out in her latest Africa Brief for Foreign Policy, the balancing act by Chad’s political elite in this election week, involves a remarkable blend of ethnic, regional and global geopolitical forces.

Incumbent transitional President Mahamat Idriss Déby’s late father, came from the Zaghawa ethnic group, which is being targeted by the RSF over the border in Sudan. RSF fighters include thousands of Chadian Arabs who could later challenge Chad’s minority Zaghawa rule, and Chad’s central location makes it easier to destabilize. The political elite had expected Déby to directly back Zaghawa rebels as his father did two decades ago in Darfur, but he has not done so. U.S. intelligence agencies warned Chad’s junta that Russian mercenaries were backing a coup attempt by Chadian rebels based in the Central African Republic. In January, Déby met with Russian President Vladimir Putin as he moved toward a Russian security partnership.

Source: HRW

But for all this huge complexity there are systematic connections that make it helpful, as a short-hand, to think of this giant region as an interconnected whole. Perhaps in doing so, we may be able to center East Africa and Horn of Africa in our mental maps and overcome our stubborn blindness to the true scale of events in the region.

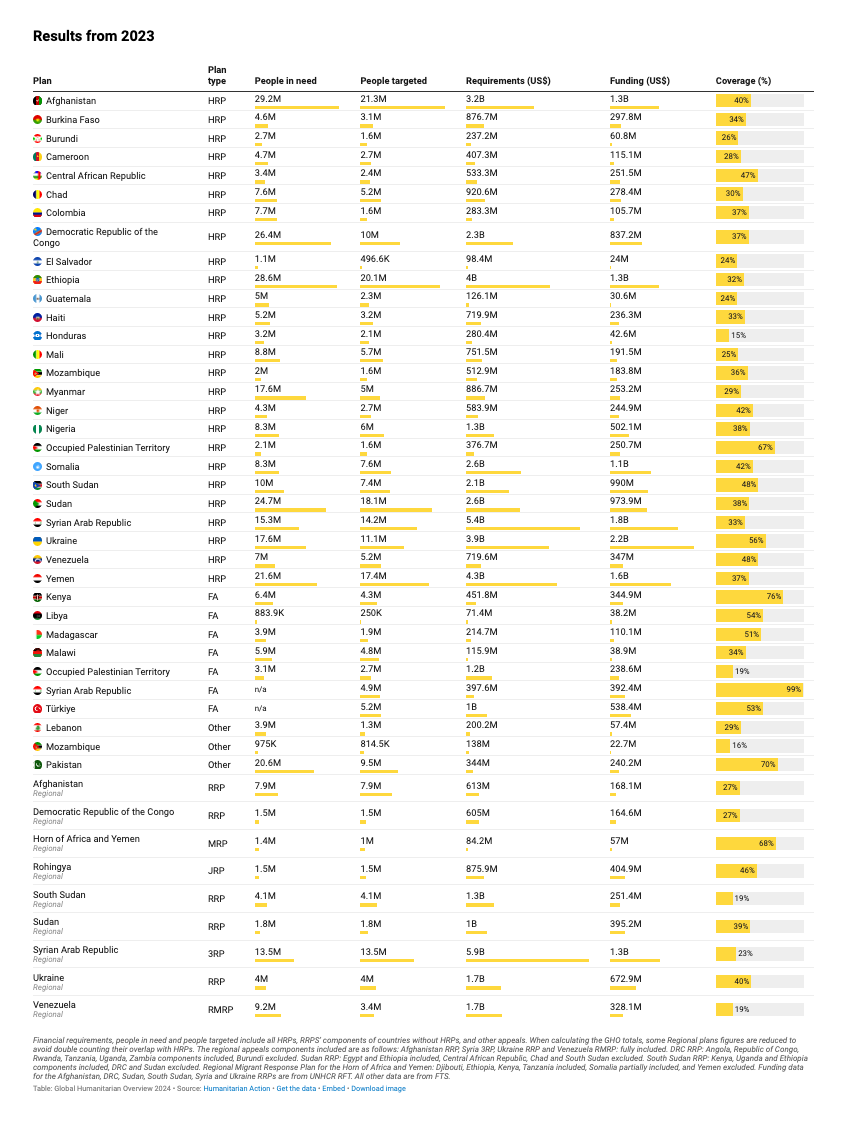

One way to think of the interconnections is to think of flows of people - fighters, workers and refugees - moving across borders. The huge crisis of displacement in Sudan is spilling over to the entire region. In April 2023 5.4 million people were counted as displaced. Today the figure is 8.6 million.

Any mapping is by necessity incomplete and finding those limits prompts further investigation. The useful CFR map above centers the Sudan refugee crisis. This has the effect of placing Uganda outside the frame and suggesting that it is unaffected by the crises of the region. What this obscures is that Uganda borders DRC to the East and South Sudan to the North and is itself a vertex of distress and displacement. Uganda, which ranks 161 out of 191 countries in terms of HDI, is currently struggling to host 1.6 million displaced people - 935k from South Sudan and over 500k from DRC.

Source: UNHCR

The region is also tied together by cross-border economic flows. Artisanal gold mining forms a common driver of economic activity and the possibility for local taxation and resource mobilization across the mega-region that stretches West across the Sahel. I addressed this connection in Chartbook 2009 at the start of the Sudan crisis.

Source: Novarica

The gold flows out of Africa to global markets by way of the Emirates. Some gold is channeled through formal deals, for instance, between the Emirati state-owned Primera mining group and the DRC. Other, large volumes of gold flow via informal channels into the largely unregulated markets in Dubai.

As Arcade Ndoricimpa explains in a fascinating article in the journal Resource Policy 2024:

A new player, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), has emerged recently in the world's gold trade. While two decades ago, UAE was not even among the world's top one hundred gold-importing countries (Blore and Hunter, 2020), today it has become one of the world's major gold trading hubs … From a total gold import value of $ 36.8 million in 2000, it reached $ 48.2 billion in 2021. … Traditionally, gold importers usually follow some standards regarding the source of gold and how it was produced, they mind whether gold originated in a conflict-affected or high-risk country or if it is associated with gross human rights violations. However, UAE follows few of these standards; … According to World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS), in 2021 UAE imported 970.4 tons of gold from 110 countries, mainly located in Africa, South America, or South Asia. Most of the imported gold is more likely to be from artisanal and small-scale gold mining … UAE is the major destination of gold from Africa … in 2021, out of the 970.4 tons of UAE's total gold imports, 57.0% (553 tons) were sourced from Africa. Among the top 11 countries where UAE sourced its gold in 2021, 9 are African countries (Mali, Sudan, Niger, Guinea, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Ghana, and Tanzania), some of them are armed conflict-affected countries. … It is reported for instance that Uganda recently apprehended a cargo ship containing 2 tons of gold which belonged to one of the rebel groups operating in the Great Lakes region. … Since little or no checks are done to verify the origin of gold, UAE becomes the destination choice for conflict and smuggled gold, receiving hence gold of dubious origins. The dirty gold is then laundered through refineries to become UAE's gold. The refined gold bars are thereafter exported to other world's gold hubs as UAE's gold …

The UAE also play an outsized role in much of the geopolitics of the region. Googling the question, I was reminded that Emirati geopolitics was one of the earliest blog posts I put up, back in 2017, in what I then called Notes on the Global Condition.

According to The Economist: “Over the past decade the UAE has been the fourth-largest foreign direct investor in Africa, behind China, the eu and America.” Perhaps, the Emirates’ most constructive contribution has been the scatter of modern port and logistics facilities along the coastline of Africa.

Source: Economist

But the Emiratis also have their hands in all three of the largest military confrontations in the region - Yemen, Sudan and the Ethiopian conflict.

Saudi Arabia and the Emirates intervened massively in Yemen, with substantial US support. Not only did they not prevail against the Houthis, but the Saudi and Emirati backed forces also warred against each other, exacerbating the conflict. In Sudan as well, both Saudi Arabi and the Emiratis are involved. As Talal Mohammad, explains in an important article in Foreign Policy.

Gulf countries have played a significant role in Sudan since Bashir’s ouster (2019). Abu Dhabi and Riyadh immediately funded the Transitional Military Council, the junta that took over, with $3bn worth of aid. At the time, Saudi and Emirati interests in Sudan were generally aligned … Both states also extracted concessions from Khartoum: Sudan provided military support for Saudi Arabia in Yemen, and the UAE mediated Khartoum’s accession to the Abraham Accords. … As of 2018, Abu Dhabi had cumulatively invested $7.6 billion … Since Bashir fell, the UAE has added another $6 bn … that include agricultural projects and a Red Sea port. In October 2022, Riyadh announced that it would invest up to $24 billion in sectors of Sudan’s economy including infrastructure, mining, and agriculture. … As emerging Middle East hegemons, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are now at odds—each seeking to control Sudan’s resources, energy, and logistics gateways by aligning with Burhan and Hemeti, respectively. … The UAE gained trust in Hemeti because RSF fighters had been active in southern Yemen since 2015 and in 2019 expanded to Libya to back Gen. Khalifa Haftar, one of the country’s rival leaders who is backed by Abu Dhabi. While Saudi Arabia has cooperated with Egypt in supporting Burhan, the UAE has collaborated with Russia in supporting the RSF through the paramilitary Wagner Group. … Abu Dhabi has kept silent about its alliance with the RSF. But reports suggest Hemeti has acted as a custodian of Emirati interests in Sudan, guarding gold mines controlled by Wagner; gold from these mines is then shipped to the UAE en route to Russia. ….While the UAE has been fighting for gold, Saudi Arabia has worked tirelessly to brand itself as a peacemaker and humanitarian in Sudan. Riyadh has sponsored cease-fire talks with the United States … provided aid to the Sudanese people both inside and outside the country, and helped evacuate many civilians out of Khartoum. Egyptian President Sisi—a Saudi ally—has also provided aid to the Sudanese military, particularly air support … The fall of Sudan under the control of either Burhan or Hemeti—and thereby either the Saudi or Emirati sphere of influence—would shift the balance of power in the Gulf … But it is unlikely that the outcome of the war will be this clear-cut: Similar to Libya, Sudan is likely to fracture even further, perhaps along ethnic and tribal lines.

The World Food Program warns that without a cessation of hostilities Sudan could become the site of “the world’s largest hunger crisis”. If this were not bad enough, to the East of Sudan, in Ethiopia a similarly gigantic crisis is brewing. Read Alex de Waal and Mulugeta Gebrehiwot Berhe in Foreign Affairs a few weeks ago (April 2024) and pause and wonder:

Arguably the worst armed conflict of the twenty-first century so far is not the one unfolding in Gaza or in Ukraine, but rather the catastrophic civil war in Ethiopia that ended 18 months ago. Also known as the Tigray war, the Ethiopian conflict took the lives of more than 500,000 soldiers and as many as 360,000 civilians, making it one of the deadliest conflicts since the end of the Cold War. Its combatants … destroyed large swaths of the Tigray region … and did enormous damage to an economy that, for the previous three decades, had helped make Ethiopia one of Africa’s more stable and rapidly developing countries. Yet equally terrible may be the crisis facing Ethiopia today. In November 2022, the Ethiopian government and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front entered a cease-fire to end the Tigray war, but true peace has never been reestablished. Since then, the government has faced a new rebellion in the Amhara region … which is fast making the region ungovernable. Another insurgency in Oromia, the country’s largest and most populous region, is continuing. … vast tracts of the country have become no-go areas. Meanwhile, much of the north, including Tigray, is plunging into famine. According to the UN, close to 30 million people—about one-quarter of the population—now need emergency food assistance, and without significant humanitarian relief, many of them could be at risk of starvation … As if the country’s domestic problems were not enough, in recent months, PM Abiy Ahmed has stirred up new tensions with neighboring Somalia, become entangled in Sudan’s civil war, and even made threatening gestures toward Eritrea, which had been Abiy’s ally in the Tigrayan war. Meanwhile, the government’s primary foreign patron, the UAE, has been funneling arms and money to Ethiopia, as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey have been doing the same to Eritrea, Somalia, and the Sudanese Armed Forces, threatening to drag the region into a proxy conflict.

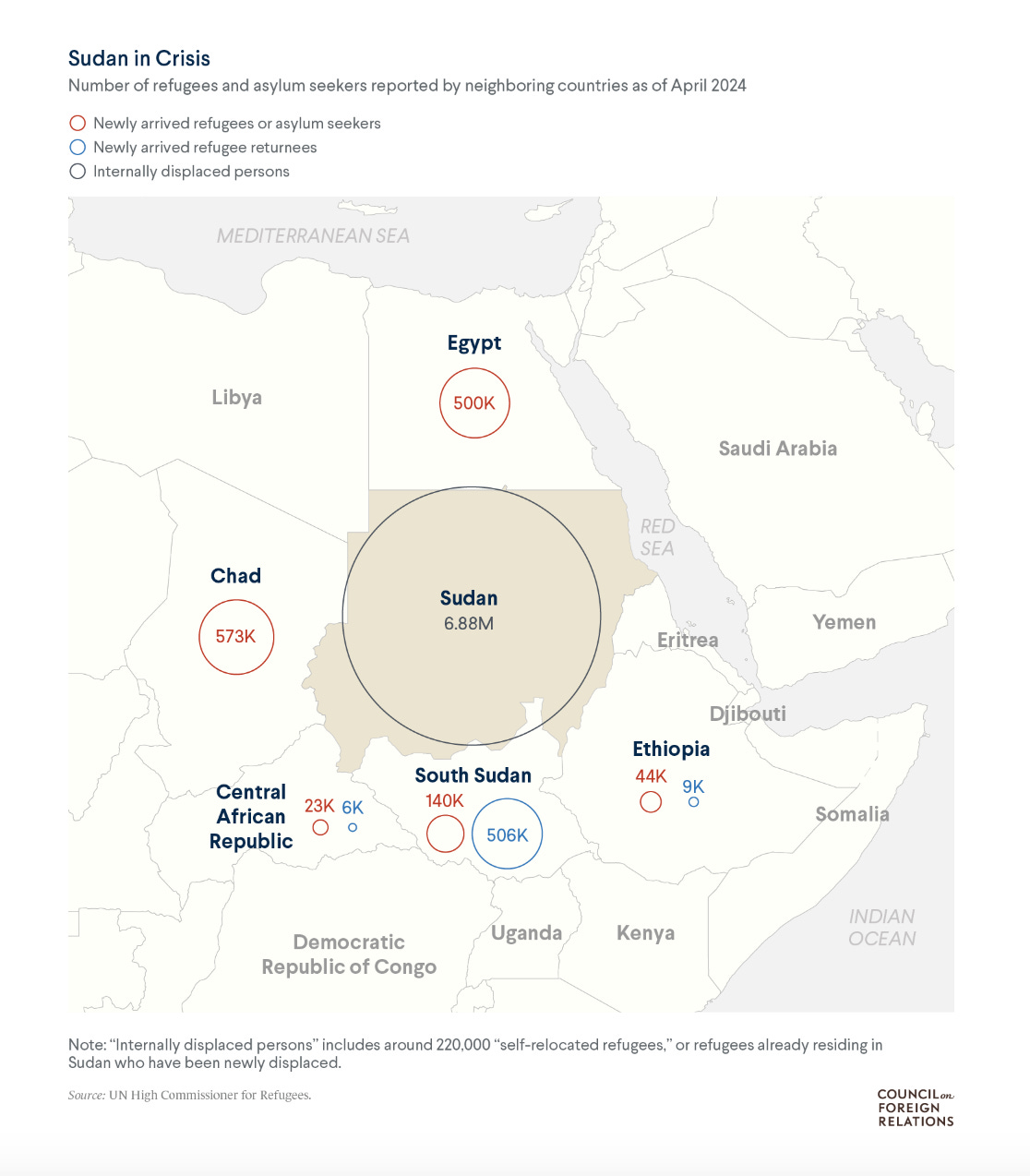

The staggering scale of these geopolitical connections from the Persian Gulf to Egypt and Moscow, is overarched by giant mecological shocks hitting the region. In the last decade, Ethiopia along with South Sudan, Somalia and Kenya have all suffered a whiplash of climate shocks.

Worst Drought on Record Parches Horn of Africa 2020-2023

Source: Earth Observatory

As the latest appeal on Relief Web notes:

Millions of people in the Horn of Africa are still struggling with the lingering effects of the severe and prolonged 2021-2023 drought (the worst in 40 years) as well as the impact of floods in the second half of 2023. Flooding caused additional livelihood loss in the drought-affected areas, including the death of some of the remaining emaciated livestock that survived the drought, and erosion of fertile lands, impacting agriculture. Recovery is expected to take between half to nearly a decade for those who lost between 80 to 100 per cent of their livelihood. …

On the Horn of Africa, Somalia has been particularly badly affected by the climate crisis. As Relief Web reported in February 2024:

Catastrophic climate change coupled with conflict has pushed over four million Somalis into severe hunger. Currently, one in five Somalis has no access to adequate food; 1.7 million children face acute malnutrition, their young lives hanging in the balance. Meanwhile, the 2024 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) is only 1.6% funded as of 27th February, leaving the most vulnerable without a lifeline. In 2023, Somalia was at the cusp of a famine. Five consecutive failed rain seasons followed by extreme flooding left 6.9 million people in need. The country witnessed unprecedented levels of displacement that saw 2.9 million people leave their homes in search of food and water.

To meet this massive pile up of crises would require a coordinated effort by actors both inside and outside the region and yet, one thing that the crises of the region also have in common is that the relief effort is dramatically underresourced. Remarkably, in the midst of a mounting hunger crisis, Somalia’s Humanitarian Plan witnessed a 50% reduction in funding between 2021 and 2023.

What conclusion can one draw, other than that the region and its people simply does not interest the rich world to the same degree as other points of conflict. For months the world discussed the Houthis and their rocket attacks on maritime traffic in the Red Sea without addressing the gigantic humanitarian crisis engulfing the entire region.

The shocking thing is that to meet the most urgent humanitarian needs of the region the relief agencies are asking, all told, for less than $20 billion. For all humanitarian emergencies around the world, the ask in 2023 was $56.7 billion. That is barely more than half the emergency package that just passed Congress, centered on America’s geopolitical spheres of interest in Ukraine, Palestine and Indo-Pacific. It is no more than the defense budget of one of the larger European countries. It is 0.05 percent of global GDP. And yet to meet the most acute needs of 363 million people, the rich countries of the world could muster only $19 billion dollars.

***

For more global coverage like this, join the club of supporters that keep Chartbook newsletter coming to your inbox.

"in the midst of a mounting hunger crisis, Somalia’s Humanitarian Plan witnessed a 50% reduction in funding between 2021 and 2023". 📢

Looks like a perfect place for Saudi Arabia to use those trillions in sovereign wealth fund, as that problem is on their doorstep. Better there than a soccer team. Of course, they have no regard for the lower classes at all, as evidenced by their importation of Phillipinos and other minorities to do their dirty jobs.