Sudan is a pivotal link in the increasingly fragile and violent geopolitics of both the Sahel and the Red Sea/Horn of Africa regions. The bloody fighting across the country that began on April 15 is the result of a clash between the two most powerful military forces in the country - General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, president since October 2021, and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemeti (Hemetti, Himedti), Sudan’s vice-president and commander of the powerful paramilitary Rapid Support Forces. The fighting is driven by rivalry between the generals, heading different factions within the security forces in the wake of the ouster of long-time President al-Bashir in April 2019. They represent different power groupings in Sudan and enjoy sponsorship from rival outside forces. Al-Burhan is connected to Sisi in Egypt. Hemeti is thought to be closer to the Emiratis. Both have links to Russia. But the condition of possibility for this clash are the political economy of Sudan to which one of the keys is gold. As the work of a brilliant group of French scholars reveals, the emergence of General Hemeti as a challenger for power in Khartoum, is a reflection of the power-shift brought about within Sudan and the wider region, by a spectacular gold rush.

***

As the International Crisis Group reported in 2019:

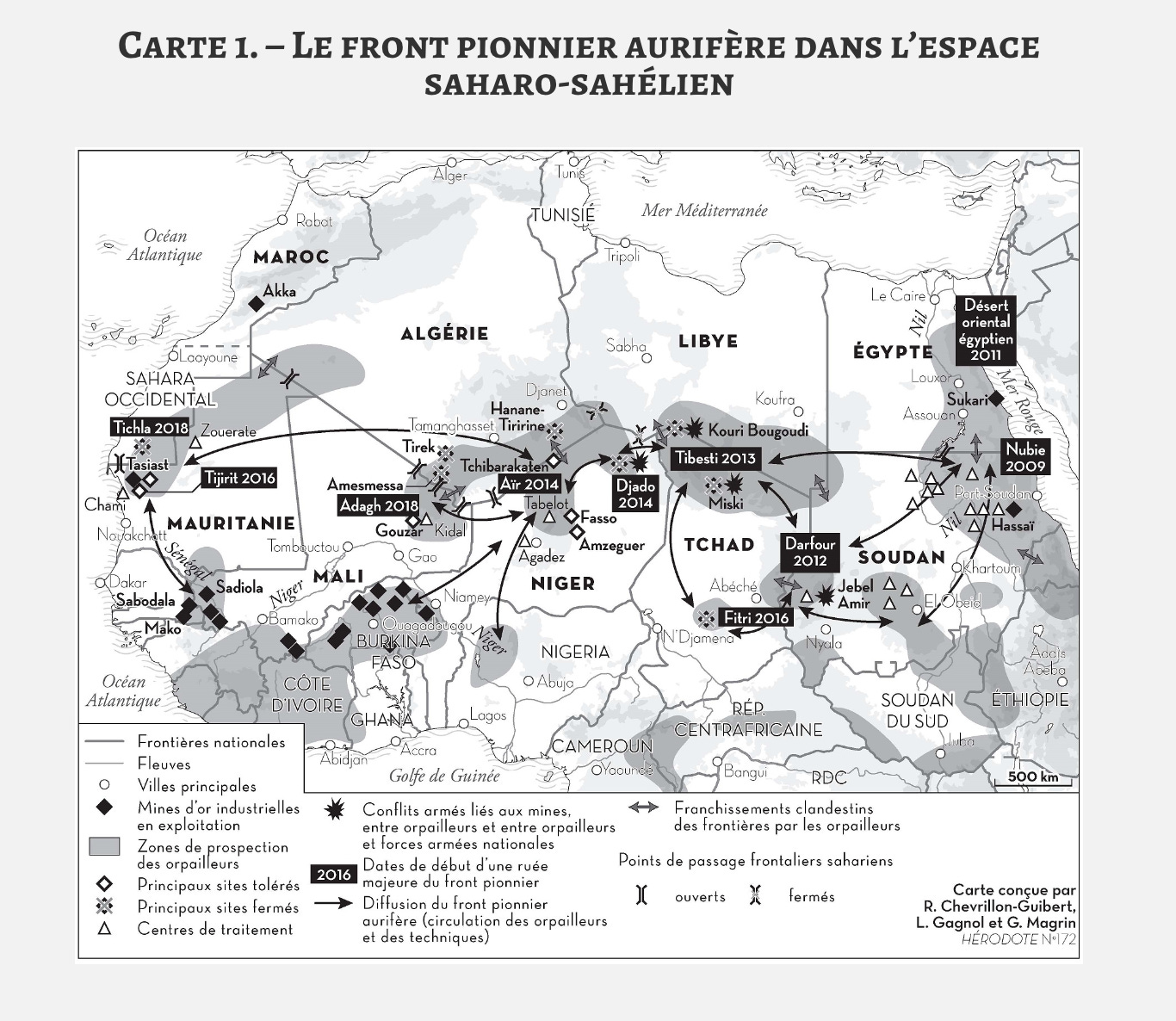

In central Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger), gold mining has intensified since 2012 due to the discovery of a particularly rich vein that crosses the Sahara from east to west. The first finds were made in Sudan (Jebel Amir) in 2012, followed by others between 2013 and 2016 in Chad (Batha in the centre and Tibesti in the north of the country), in 2014 in Niger (Djado in the north east of the country, Tchibarakaten to the north east of Arlit, and the Aïr region in the centre north), then finally in 2016 in Mali (the northern part of the Kidal region) and Mauritania (Tasiast, in the west). The cross-border movement of experienced miners from the sub-region, notably from Sudan, Mali and Burkina Faso, has fuelled the exploitation of these sites. These recent discoveries come in addition to the gold already mined in Tillabéri (western Niger), Kayes, Sikasso and Koulikoro (southern Mali), and various regions of Burkina Faso, making artisanal gold a hugely important issue in the Sahel.

Source: Raphaëlle Chevrillon-Guibert, Laurent Gagnol, Géraud Magrin Hérodote 2019

As it has swept from East to West, the gold rush has been rearranging populations, economic, social, political and military relations across the Sahel. It is a moving frontier of artisanal production similar in some ways to the astonishing helter-skelter development of cocoa planting that I analysed in Ghana and Cote D’Ivoire in Chartbook 196.

The activities of Africa’s artisanal miners have attracted media coverage around the world. This tends to concentrate on the primitive conditions in which they work. Dramatic pictures of artisanal mining conjure up comparisons to the “19th century” or some other imagined past. Frequently comments are made about the stark contrast between the smartphones that the rare earths end up in and the primitivism of the conditions in which gold, coltan etc are mined.

The contrast between affluence and poverty is only too real. But the idea that they reflect different eras of history, or different stages of development is an illusion.

The activity of artisanal mining is quite new in most of the places in Africa that have been caught up in the current resource boom. It has certainly never been practice on this scale before. Giant artisanal mine sites in Mali or Darfur are no more more natural or native to Africa than the deforested cocoa regions of CdI. Furthermore, all this activity involving millions of people organized across huge distance, would not be possible without the extensive use of modern technologies at the African sites of production. In 2018 Mali registered 150 cellphone subscriptions per 100 inhabitants and rising. But there is one gizmo of which the Sahel’s gold miners can claim to be the most important users worldwide - the cheap portable metal detectors, which became widely available in the region around 2008-2009.

By 2009 the Sahelian demand for metal-detectors was so intense that it produced a global shortage of the equipment, with order books backed up for 6-9 months, and Chinese imitators scrambling to steal technology from Western market leaders. At one point the British army in Afghanistan blamed its lack of mine detectors on the African mining boom.

The communities that have been created by the gold rush are anything but “traditional” or “archaic”, like mining camps of the 19th-century California, they are wildly cosmopolitan places, peopled by migrants from across Africa, mixing communities - Muslim and non-Muslim - and opening up novel routes of trade and communication. This piece about communal mixing and life in gold regions of Niger gives a graphic description of the makeshift sociability that functions in the mining camps and the hardship these communities are forged under.

A fascinating snapshot of the level of activity in the region and its material needs was provided in December 2020 by a coordinated interpol operation in which regional police forces conducted raids on smuggling hotspots in Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali and Niger. In the course of a week the police confiscated the modest total of 50 firearms, 6,162 rounds of ammunition, 1,473 kilos of drugs (cannabis and khat), 2,263 boxes of contraband drugs, 60,000 litres of contraband fuel … and 40,593 sticks of dynamite!

Unsurprisingly, mining on this scale draws in more or less organized groups of men with guns who seek to establish control, control commerce, tax and in some cases even organize production. Across the Western Sahel, gold figures in the background of the jihadist revolts.

Control over gold is also a key stake for the juntas who have recently seized control in Guinea, Burkina Faso and Mali. The gold has also attracted interested from the Russian mercenary forces that have been operating on an increasingly large scale, especially in Central African Republic.

***

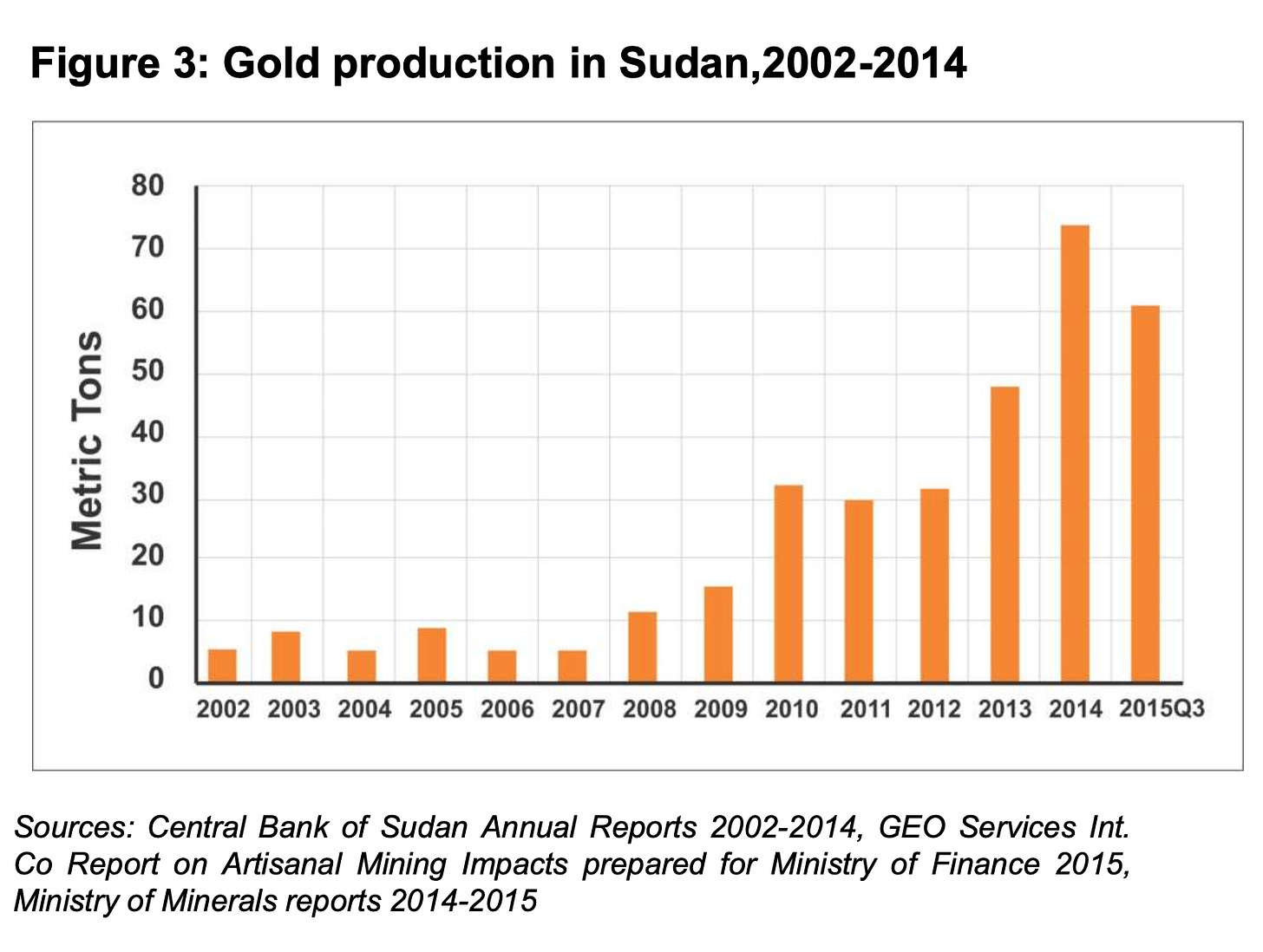

Though the Jihadi threat tends to draw most outside coverage of the Sahel to the Western end, it is Sudan that anchors the Sahel gold belt in the East. And it is Sudan from where the gold rush began. According to the official statistics Sudan emerged quite suddenly in the 2010s as by far the largest of the Sahel producers, third only to South Africa and Ghana in Africa as a whole. Unlike the Western Sahel as presentation by the Sudanese Mining authorities spelled out, mining in Sudan goes back to antiquity.

Having said that, until the 2010s the vast majority of Sudan’s 45 million people support themselves with agriculture. Tensions between pastoralist and farmers are a key fissure in Sudanese society as in much of the Sahel and East Africa. But agriculture doesn’t generate hard currency to pay for imports, or much tax to operate a state. So commodities for export have long been key to the functioning of the Sudanese state and its politics.

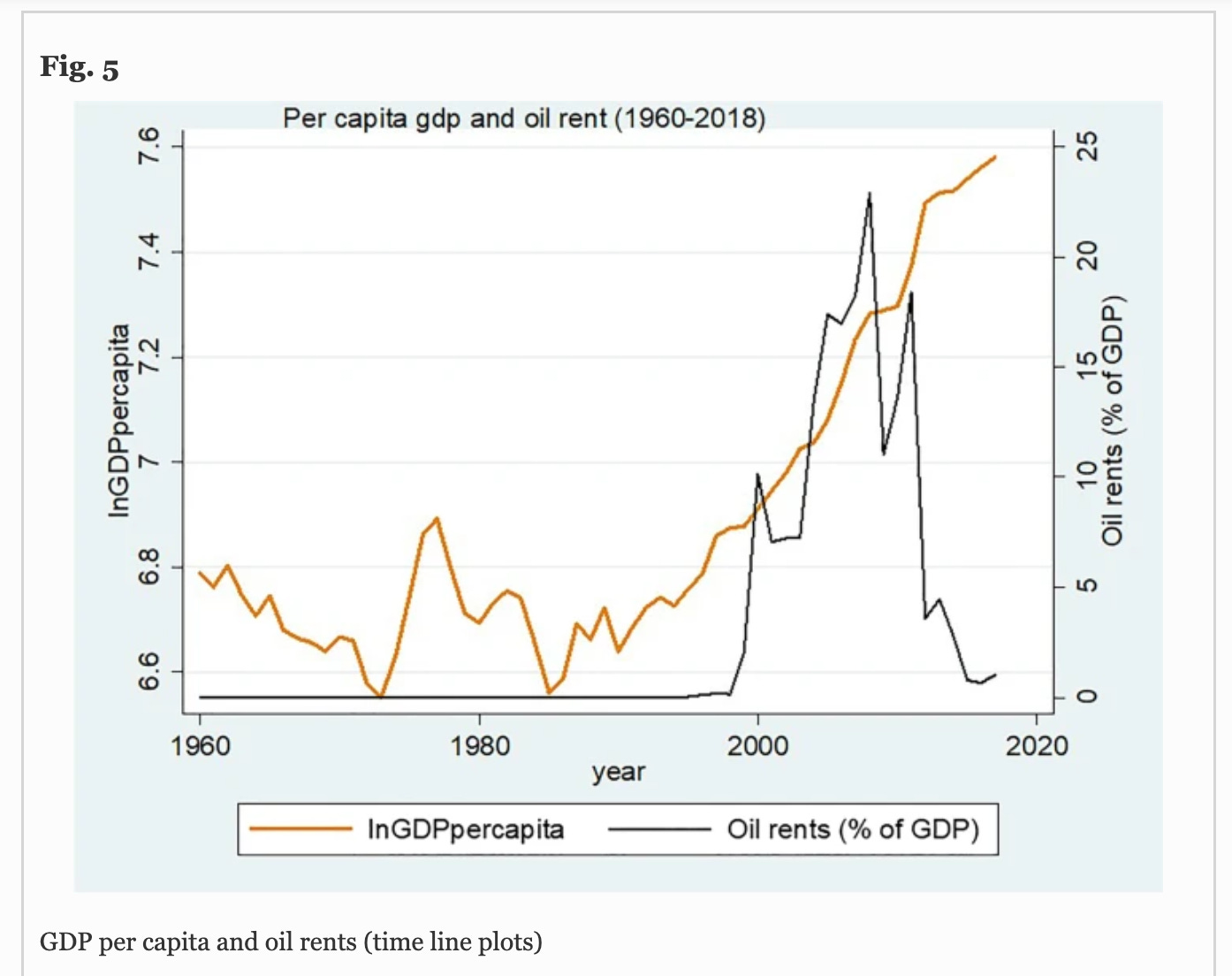

Source: Ali, Murshed and Papyrakis et al Mineral Economics 2023

The Islamist regime that ruled the country from 1989 based itself from the late 1990s onwards not on gold but oil. Oil revenues were abundant enough to pay for infrastructure work such as the tarmacking of thousands of km of road and the construction of dams. They also had the attractive attribute of being generated from enclave industrial facilities that did not disturb the structures of Sudanese society or power. The oil fields were overwhelmingly in the South where Khartoum ruled at a distance over a mainly Christian population. In 2011 South Sudan broke away to form an independent state. The impact on the rest of the Sudanese economy was devastating. Whereas Sudan in 2010 benefited from oil exports of $ 9.69 billion, by 2015 its oil earnings were reduced to a paltry $627 million. This terrible blow triggered Khartoum into adopting a brutal austerity regime. But as Raphaëlle Chevrillon-Guibert shows in a fascinating report, the loss of the Southern oil fields did not come as a surprise. From 2005 onwards, anticipating eventual secession, Khartoum was looking to diversify its exports, prioritizing agricultural and mining development in the Northern part of the country.

Sudan has promising deposits of chromium, manganese and even uranium. But the obvious prize was gold. The original vision of the al-Bashir regime was to turn Sudan into an industrial gold producer like Ghana or South Africa. The regime would license production by a handful of large companies on the enclave model familiar from the oil industry. This was both “modern” and it would leave the existing structure of politics and society in place. As research by the US NGO Enough explains:

Until 2012, 74 percent of the country’s proven gold reserves were being managed through just two companies: the Canadian-Egyptian-Sudanese joint venture Ariab and the Moroccan-Sudanese venture Managem. Those companies’ concessions are in Red Sea and Nile states respectively, far from the country’s war zones. Although these large-scale mines attracted criticism for their poor labor conditions and negative environmental impact, the country’s gold trade was never directly touched by its wars.

Under the company concession regime, gold production remained contained. Between 2005 and 2011 production did increase significantly, but from a very low base. And then came the explosion of 2012.

As Jérôme Tubiana described it in Foreign Affairs:

In April 2012, a small team of wandering miners discovered gold in the Jebel Amir hills of North Darfur, Sudan. One of the mines was so rich -- it reportedly brought millions of dollars to its owners -- that it was nicknamed “Switzerland.” Diggers rushed in from all over Sudan, as well as from the Central African Republic, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria. After a much-publicized visit by Sudan’s mining minister and the governor of North Darfur state, their number may have reached 100,000. …

Between 2011 and 2014, rather than Sudan becoming the home of a tightly managed enclave gold mining industry, Northern Sudan, and especially Darfur, became the theatre for a full-scale gold rush. Sudan’s gold production surged to 70 million tons. Gold sales rose from ten percent of Sudan’s exports to 70 percent. In 2015, 1 million workers and 4 million dependents were supported by the mining industry, most but by no means all were Sudanese. The techniques used were primitive and dirty. Mercury was used to extract the gold and sodium cyanide to process the tailings, resulting in huge health risks for the workforce and extensive environmental damage. NGOs and local authorities have protested these conditions but the priority has been production.

Given this helter-skelter expansion the question of control was paramount. Nominally from 2012 it was the Central Bank that had the exclusive right to purchase artisan-mined gold and to sell it abroad. But the Central Bank has struggled to match international prices. Its efforts to do so by printing local currency en masse have sparked bouts of severe inflation. And efforts by the authorities to corral the private minters have been anything but consistent. The result is that perhaps as much as 90 percent of all gold produced in Sudan is exported through dark channels particularly to Dubai, which has become the major entrepot for gold exports from the Sahel artisanal mining boom. If 90 percent is the correct figure, as CNN sources estimate, then in 2022 $13.4 billion worth of gold production was smuggled out of Sudan. It could be even more.

The question is who organizes, sanctions and ultimately permits smuggling on this scale. The giant gold rush in Sudan exploded into the Darfur region, which since 2003 had been one of the chief battlefields of the Sudanese civil wars. In January 2013, the gold mining area of Jebel Amir in North Darfur witnessed a mass ethnic cleansing and forced clearance of much of the local population, overseen by Musa Hilal, an Arab tribal leader and infamous Janjaweed commander. In the course of the war, the Janjaweed, were accused of killing perhaps 300,000 civilians on behalf of al-Bashir’s regime. All the while, the gold flowed from Jebel Amir to Sudan’s central bank and from there to Dubai and the markets of the UAE. Sudan was forced to accept heavy discounts on its gold, but given American financial sanctions it was an invaluable source of foreign currency.

Musa Hilal resorted to any means of force necessary to control the Jebel Amir region. But his local standing and growing influence also made him a target. Following a rebellion by the local population, the man who moved to supplant and ultimately to subordinatet Hiala by 2017 was Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, a Brigadier General in the Janjaweed. He is from the same ethnic group as Hilal but lacking his clan standing. At the end of fighting it was General Dagalo also known as Hemeti, a man without proper education who struggles to express himself in either proper Arabic or Sudanese colloquial Arabic and who many suspect of being Chadian, that emerged as the ruler of Jebel Amir. Dagalo and his brother, through their family vehicle the Al Gunade company, have thus become kingpins in Sudan’s gold economy. On that basis Hemeti emerged not just as a national powerhouse, but as an independent international actor. As many as 16,000 of his heavily armed RSF militia were deployed alongside regular Sudanese army as part of the Saud-coalition in Yemen. The RSF control trade and migration on the border region to Libya and have intervened militarily. And to further consolidate his grip Dagalo has struck up an unlikely relationship of patronage with Russia.

This may seem far-fetched. But the regime of sanctions imposed on Sudan by the US and the punishments meted out to French bank BNP in 2014, had the effect of freezing out much Western investment. Russia filled the vacuum. Moscow started engaging with Sudan at the latest in 2017 when then President al-Bashir was hosted by Putin in Sochi. As the New York Times reports:

Within weeks (of the meeting of al-Bashir with Putin), Russian geologists and mineralogists employed by Meroe Gold, a new Sudanese company, began to arrive in Sudan, according to commercial flight records obtained by the Dossier Center, a London-based investigative body, and verified by researchers at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies. The Treasury Department says that Meroe Gold is controlled by Mr. Prigozhin, and it imposed sanctions on the company in 2020 as part of a raft of a measures targeting Wagner in Sudan. Meroe’s director in Sudan, Mikhail Potepkin, was previously employed by the Internet Research Agency, the Prigozhin-financed troll factory accused of meddling in the 2016 United States election, the Treasury Department said. Meroe Gold’s geologists were followed by Russian defense officials, who opened negotiations over a potential Russian naval base on the Red Sea — a strategic prize for the Kremlin, suddenly within reach.

By 2019 al-Bashir faced opposition from within the army and from the pro-democracy movement. What was keeping him in power were above all the RSF under Hemeti’s command. But from 2017 onwards Hemeti became increasingly suspicious of businesses close to al-Bashir that were muscling into his territory. It was Hemeti’s decision to switch sides that opened the road to the coup that removed al-Bashir from power in April 2019.

Following the removal of al-Bashir Moscow backed both major military factions. Moscow cultivated Sudan’s regular military leadership in Khartoum with a view to establishing a permanent naval base on the Red Sea. At the same time, it worked with Hemeti and his militia in the gold fields. His Darfur base welcomed Russia’s own gold refining operations in Sudan and served as a convenient connecting point for their mercenary activities in both Central African Republic and Libya.

After a two-year experiment with a transitional civilian government, both the major military factions in Sudan and their Russian backers had had enough. In a transaction I wish I knew more about, in the spring of 2020 Hemeti’s group announced the official return to government control of the Jebel Amir mines. But who was the government? In October 2021 with Russian backing the military factions put an end to the civilian transitional administration. It has been rumored that the coup may have been motivated by the desire to end civilian administrative obstruction of collaboration between the Sudanese military and the Russians. In the months prior to the coup Russian operatives had become increasingly nervous about US oversight of their activities and had been looking to create Sudanese shadow companies to hide their tracks. This had been resisted by civilian Sudanese corruption watchdogs who bitterly resent the idea of a sellout of their country to Russia.

After the coup in October 2021 that civilian interference ceased. Russian warships docked in Sudanese ports and on February 24 2022, the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, ex-Janjaweed militia leader and gold tycoon Hemeti was in Moscow hobnobbing with Lavrov and Russian top brass.

If you are curious about Gen Mohamed Hamdan aka Hemeti’s diplomatic forays you can follow the warlord’s account on twitter where he gives a running account of his diplomacy, including conversations with Secretary of State Blinken.

***

How the power struggle in Sudan will play out is an open question. Most recently a US diplomatic convoy was caught in the crossfire in Khartoum and Cairo is under pressure to send more troops into the country to rescue those already taken prisoner by RSF. Hemeti is spoiling for a fight, he relishes the prospect of positioning himself. as the successor to al-Bashir as Sudan’s defender against the over-mighty Egyptians. As Chevrillon-Guibert, Ille and Salah summarize it, what we are witnessing is a truly remarkable catapulting of a provincial warlord of humble origins: “who belongs neither to the Darfurian elite nor to the Nile riparian elite historically dominant in the country” to the status of a global player. “Himeidti represents the intrusion of new, formerly peripheral, forces into the higher levels of power, by capturing natural resources and by pure and simple brutality”. He is a fitting product of the gold rush.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

yes, it is 70 tons, substantial but not big compared to the leading gold producers. see

https://www.statista.com/statistics/264628/world-mine-production-of-gold/

Hi Adam - I'm sorry to use this area to request some technical support, but I haven't had any responses via Substack support or your email. I have a paid subscription, but I want to transfer it to a colleague. I have changed the record to her name, but it won't let me change the email. If this message reaches you, can you please email me at jonesh@rba.gov.au and we can go from there? Kind regards, Helen Jones