Chartbook 321 Ruination, trade interruption and downgrades: The Middle East economy under the shadow of escalating violence.

Prompted by the horrifying escalation of violence in the Middle East, I have pulled together some recent economic reports and data on the region.

The Myth of the Middle Eastern Economy: disaster zones v. “flyover states” & Asian-orientated energy exporters.

… for decades, Washington has mistakenly interpreted the Middle East’s economy as cohesive, fueled by the Gulf’s oil and gas. … As the Gulf economies grew, the officials anticipated that the region’s economic health would hinge on local bailouts and investments—an expectation that to some degree bore out after the Arab Spring, when Gulf states vied to rescue Egypt. … But Middle Eastern countries have long boasted starkly different economic capacities, and the regional economy has been divided between energy exporters and importers. Even that dichotomy has now become much more complex. Since the Arab Spring, the Gulf states’ advantages have far outstripped the market and technology access sought by their energy asset-rich but poorly governed neighbors such as Algeria, Iran, Iraq, and Libya. Moreover, since 2016, the wealthier Gulf states (Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE) have been less inclined to provide aid, investment, and trading opportunities to their neighbors as they seek to invest domestically and prepare for their own post-carbon future. …. In practice, the Middle East is becoming a set of “flyover” states that are either mired in conflict (Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Yemen) or stagnating (Egypt, Iran, and Jordan) as their growth and linkages to global markets shrink. In April 2024, the World Bank found that on average, the Middle East and North Africa region has a nearly a 90 percent debt-to-GDP ratio. Ten years ago, this average ratio was more like 75 percent. … Meanwhile, other states such as Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are progressing in their ability to generate non-oil growth and diversify their economies. These energy exporters are also borrowing heavily, now averaging a 30 percent debt-to-GDP ratio compared with ten percent a decade ago. But this borrowing is paying off: the Gulf national oil companies are now more likely than the big U.S. oil companies to boast major renewable-energy projects and investments. These countries’ economic opportunities are secure because of the Asian markets they are now accessing, not because of their ties within the Middle East or Europe. The International Energy Agency has projected that between 2022 and 2028, 90 percent of the growth in oil demand globally will come from the Asia-Pacific region, which will also drive increased demand for liquefied natural gas as its countries pivot away from coal.

This very smart piece by Karen E. Young Foreign Affairs is a great read and merits a much more extended discussion.

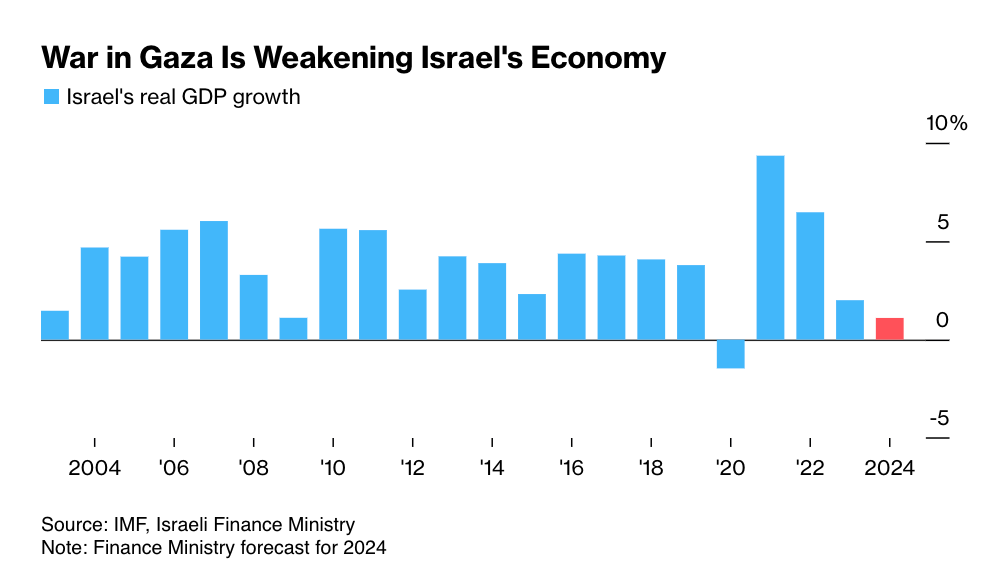

Israel has the upper hand in its brutal escalation of military offensives against both Gaza and Hezbollah. It is rich and has deep pockets, but it is also coming under financial pressure.

For much of last decade shekel bond yields were lower than those of US Treasuries … no longer.

Israel was downgraded for the second time this year by Moody’s Ratings as the economic costs mount from almost 12 months of fighting in Gaza and an worsening conflict with Hezbollah. Moody’s cut Israel by two notches to Baa1 from A2, the ratings company said late on Friday, leaving the country three steps above non-investment grade. The outlook remains negative. The “geopolitical risk has intensified significantly further, to very high levels, with material negative consequences for Israel’s creditworthiness in both the near and longer term,” Moody’s said in its unscheduled announcement. “The intensity of the conflict between Israel and Hezbollah has increased significantly in recent days.”

Moody’s decision was made even before Israel struck Hezbollah’s headquarters in southern Beirut on Friday in the heaviest attack on the Lebanese capital in almost two decades. The development was a major escalation of hostilities. The conflicts have proved financially costly for Israel. Government spending and the budget deficit are soaring, while sectors such as tourism, agriculture and construction have slumped. Israelifficials estimated war costs through the end of next year would amount to roughly $66 billion, or more than 12% of gross domestic product. That figure was based on the fighting with Hezbollah not escalating into an full-blown confrontation.

“Longer term, we consider that Israel’s economy will be more durably weakened by the military conflict than expected earlier,” Moody’s said. … Israel’s 12-month trailing budget deficit stood at 8.3% of GDP in August. The country’s full-year fiscal gap is set to be the widest this century, excluding the Covid-19 pandemic. This month, the finance ministry cut its 2024 economic growth projection to 1.1% from 1.9%. The estimate for next year was lowered to 4.4% from 4.6%.

Source: Bloomberg

West Bank and Palestine economies in meltdown

According to the World Bank, Gaza’s GDP in the last quarter of 2023—reflecting only the damage wrought by the war’s beginning—was 86 percent lower than it had been in the last quarter of 2022, and food insecurity now affects 95 percent of the strip’s inhabitants. In the West Bank, unemployment surged from 13 percent in the third quarter of 2023 to 32 percent by the end of that year, the highest recorded rate. The ruling Palestinian Authority has been pushed to the brink of outright financial collapse; a June analysis by the International Crisis Group found that its debt to commercial banks and its arrears to its own pension fund has mounted to as much as $11 billion.

Source: Karen E. Young Foreign Affairs

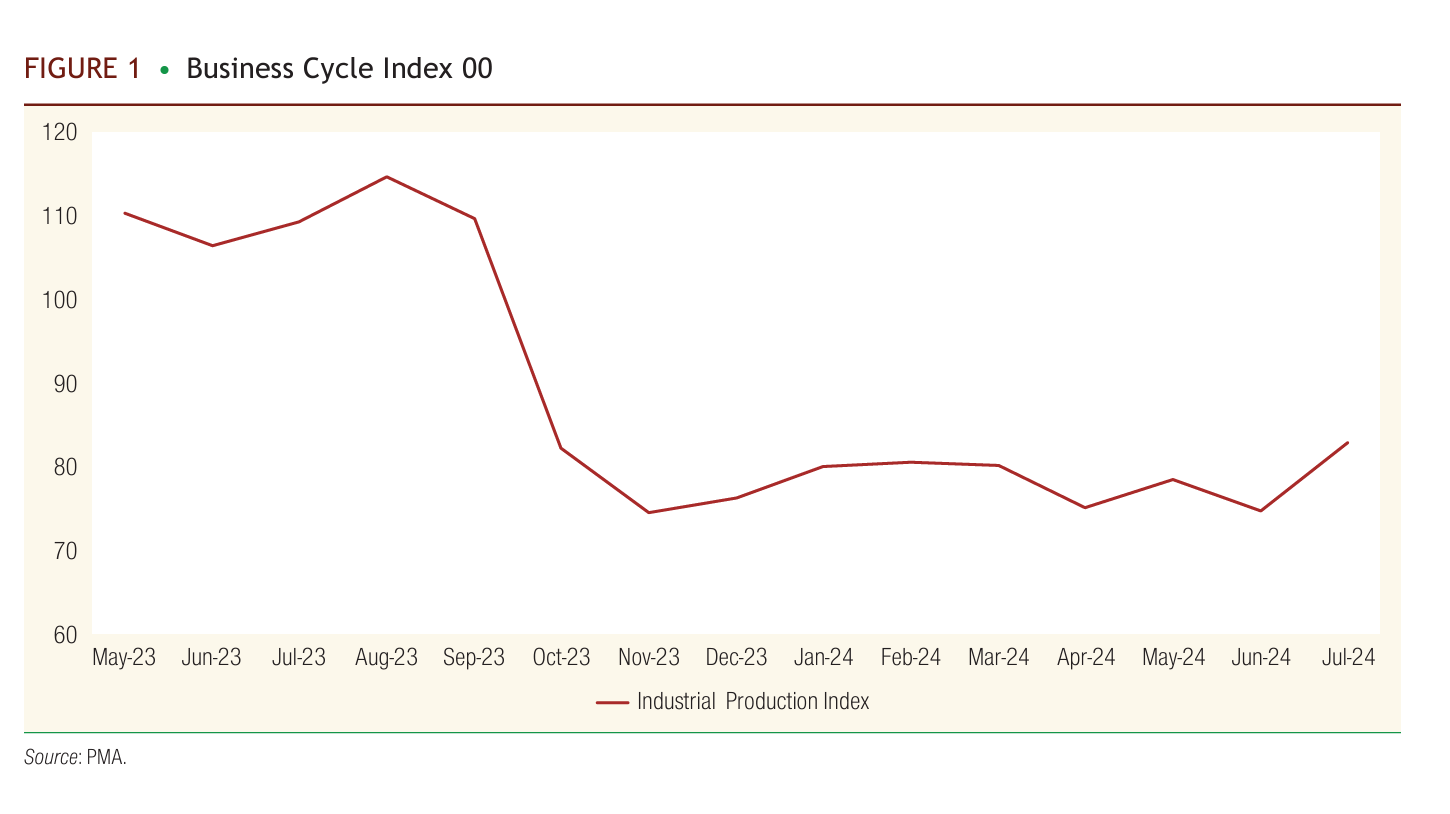

Whilst Gaza has been destroyed, the economy of the West Bank in Q1 2024 had plunged by 25 percent yoy

The West Bank economy under stress

The divergence of the Gazan and West Bank economies before 2023 was already stark and reflected the long-term blockade imposed on Gaza by Israel.

Source: World Bank

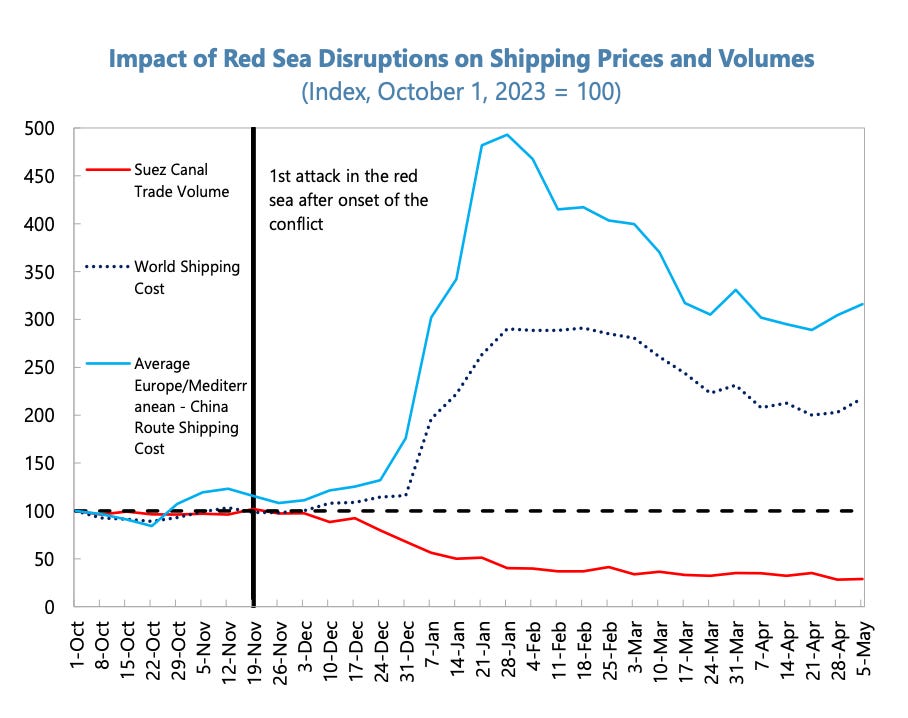

Red Sea disruptions hit shipping volumes and prices in the region.

Source: IMF

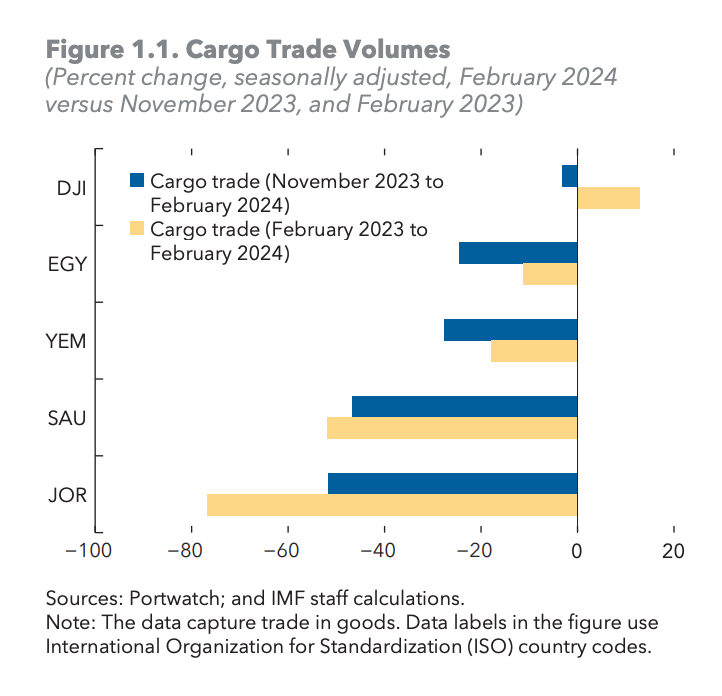

Security risks in the Red Sea and the interruption of trade is hitting many regional economies

Moreover, security risks in the Red Sea continue to raise broader concerns about the impact of the conflict on trade and shipping costs, as 12–15 percent of global trade passes through the Suez Canal (UNCTAD 2024). Egypt’s economy is particularly exposed to these disruptions, having received about 2.2 percent of GDP in annual balance-of-payment receipts—over $700 million per month—and 1.2 percent of GDP in fiscal revenue from Suez Canal dues in 2022/23. However, between the first drone attacks in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait in November and the end of February, trade through the Suez Canal dropped by more than half, from 38 million metric tons to 16 million metric tons. The reduction in cargo trade volumes is also affecting other EM&MIs, with their Red Sea ports experiencing lower throughput (Figure 1.1). For example, by the end of February, Jordan’s exports and imports through the Port of Aqaba had been cut nearly in half since the beginning of the disruptions in November, although some trade flows have since been redirected through other routes. In Saudi Arabia, port activity has decreased in Jeddah as the authorities shift traffic to the port of Dammam, located in the Persian Gulf.

Source: IMF

The impact of conflict is compounded by deliberate oil production cuts

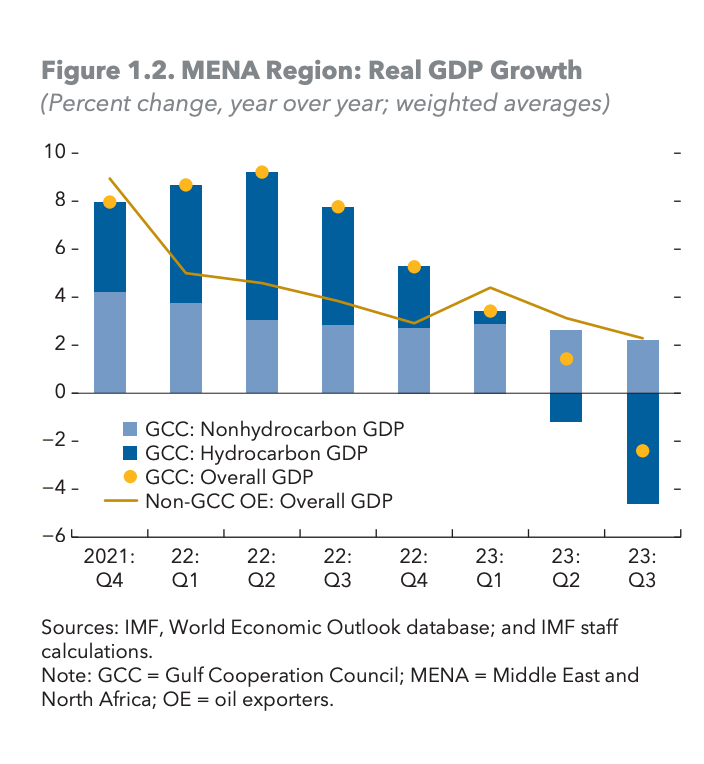

Voluntary oil production decisions largely drove growth in MENA oil and gas producers in 2023. Notably, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries experienced a marked deceleration in hydrocarbon growth following several rounds of voluntary production cuts by some OPEC+ countries. Consequently, real GDP growth in the GCC slowed sharply (to 0.4 percent), despite robust nonhydrocarbon growth driven by continued benefits from reforms to diversify the economy, high domestic demand, and gross capital inflows. Activity in non-GCC oil exporters was broadly stable, with heterogeneity across countries reflecting higher oil exports (Islamic Republic of Iran, Libya) and fragility (Iraq) (Figure 1.2)

Source: IMF

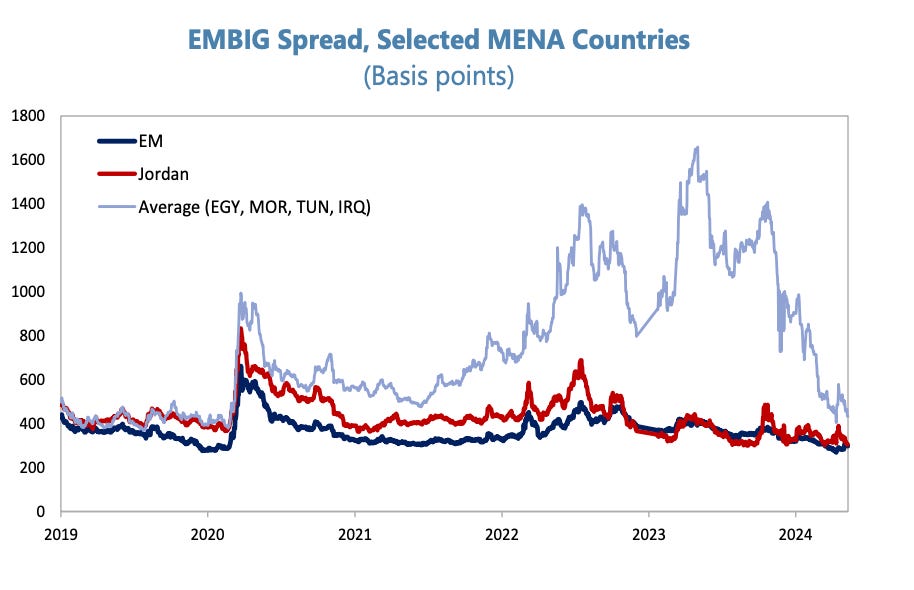

As global EM have recovered from the shock of Fed tightening, MENA is an exception. Since 2023 the region has continued to suffer capital flight and Lebanon, Pakistan and Tunisia remain in serious financial distress.

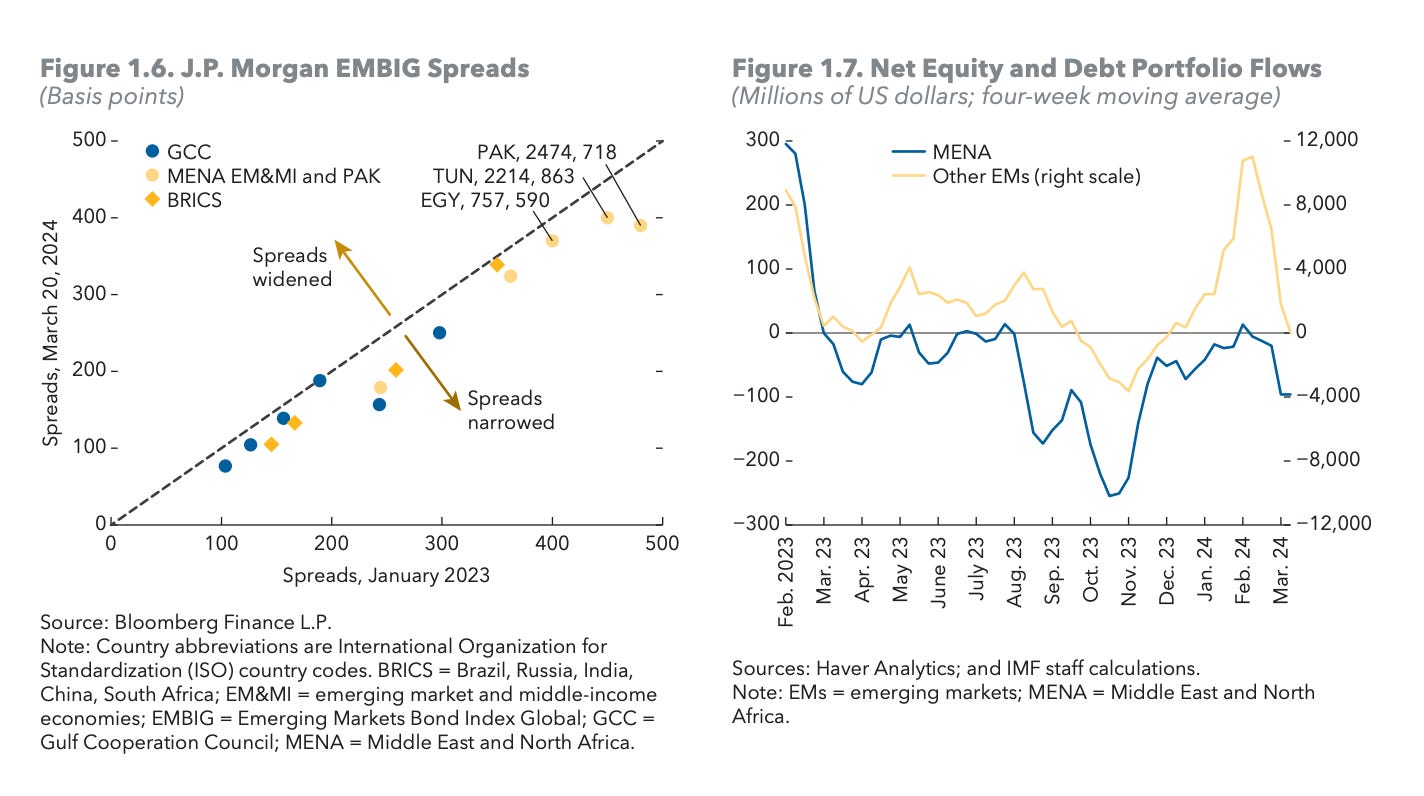

Sovereign spreads for global emerging markets have narrowed over the past year and are close to early 2023 levels for most MENA countries (Figure 1.6). However, they remain at distressed levels (more than 1,000 basis points) for Lebanon, Pakistan, and Tunisia. Meanwhile, in contrast to other emerging markets, the MENA region has largely experienced capital outflows since early 2023 (Figure 1.7). The region’s EM&MIs have not issued Eurobonds since the first half of 2023 (except for Jordan), and this issuance came at a higher cost than for GCC countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). The continued reliance on domestic financing risks further exacerbating the sovereign-bank nexus, given the already-high exposure of banks to sovereign debt in some EM&MIs (notably Egypt and Pakistan).

Source: IMF

To get Chartbook newsletter to your email inbox most days of the week, check out the subscription options below:

“brutal” escalation by Israel

“disruptions” in Red Sea by not mentioned

Not exactly fair and balanced

Love how this guy said the last four years of economic policy were at least "an A-" and the negative externalities of those policies is just, all of this, horrifying.

But of course being a hoity toity academic in the ivory tower, it doesn't count because it happened to brown people in a country that isn't America, so be sure to go vote for more of it, right?