Chartbook 315 Talking about Bangladesh. Or, rather, why aren't we talking about Bangladesh?

Apropos the questions “Do we know what time it is?” and “How do we actually inhabit the global condition?”, I’ve been preoccupied these last few weeks by how little the world that I am in, is talking about Bangladesh.

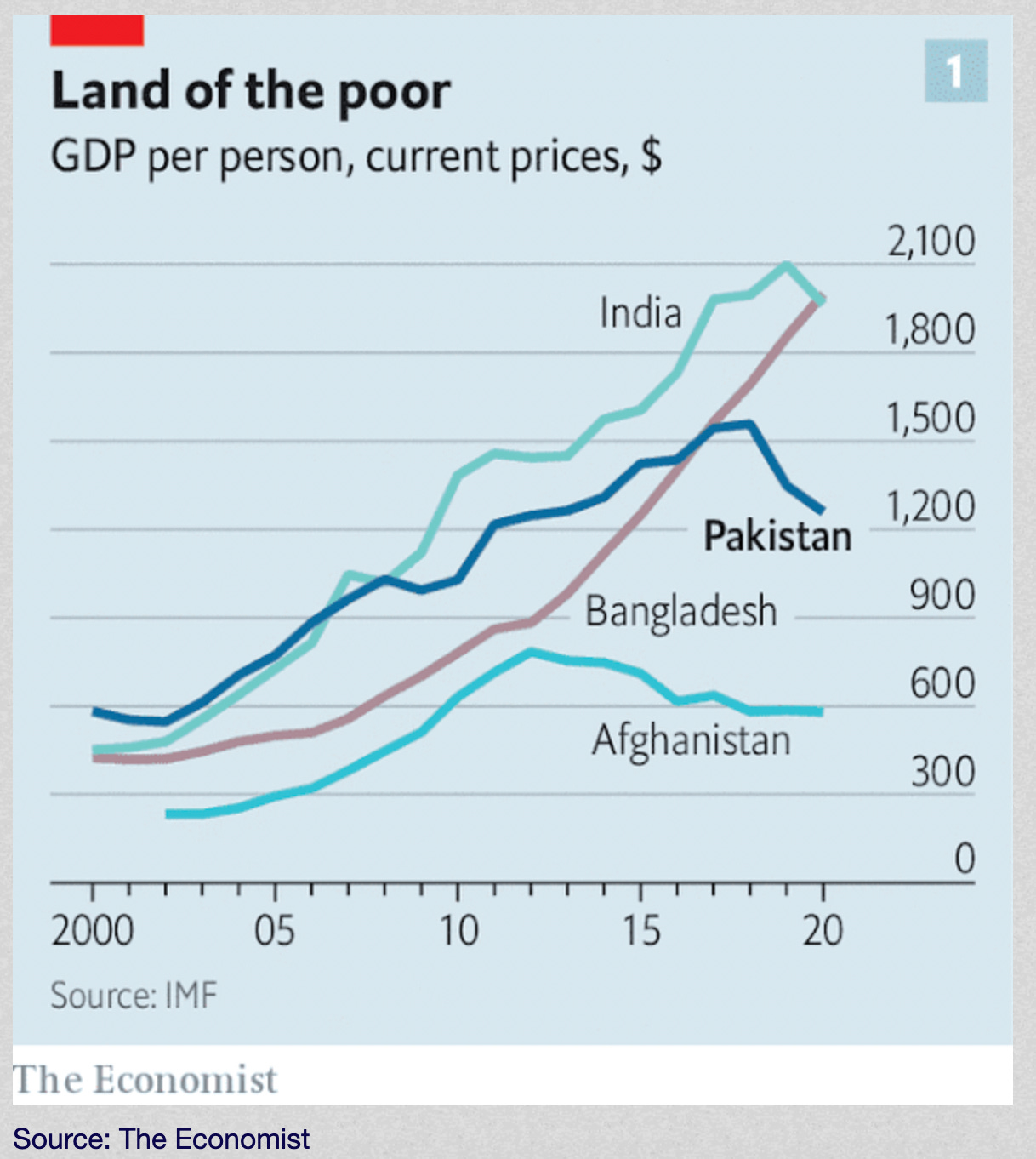

I started thinking about Bangladesh regularly after writing a section of Shutdown on the impact of COVID on the global garment sector, a sector in which Bangladesh plays a pivotal role. Bangladesh is the 8th most populous country in the world. In the last half century and particularly in recent decades it is one of the great development success stories. Bangladesh has often been touted as a story of pro-poor-growth driven above all by NGOs. This graphic from the Economist is typical of the genre. From a desperately low level in 2000, it shows Bangladesh overtaking first Pakistan and then India in GDP per capita.

Bangladesh is one of the most-climate exposed “big” country in the world. As the IMF reported back in 2019, by 2050, Bangladesh will lose 17% of its territory due to rising sea levels, resulting in the loss of 30% of the country's agricultural land.

On August 5 2024, barely a month ago, a student-led revolution toppled the elected authoritarian regime of Sheikh Hasina and rather than celebrating this fact (or denouncing it), the really eerie thing is that it is as though nothing happened. Check out FT, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy etc to see how minimal the reaction has been. I’m really grateful to Cam Abadi and the Foreign Policy for giving us the space to talk about Bangladesh on the pod a few weeks back.

It was good to engage with the news on the show, but tbh I’ve remained haunted ever since.

What does it mean that this dramatic upheaval can be happening in this huge and important country and “we” are largely oblivious? The only conversations I have had about Bangladesh other than with Cam are with Uber drivers in Manhattan. They were generally in a buoyant mood.

Returning to the question of the last newsletter: Are we actually capable of inhabiting our reality in this moment? Are we actually capable of being in medias res?

The question has become all the more urgent for me as I’ve read more about Bangladeshi history and realized the extent to which Bangladesh was present in global discourse half a century ago, at the time of independence in 1971.

Of course, you might say that we are simply overwhelmed. Our modern world is so much more complex. There were 3.7 billion people on the planet in 1971. Now there are 8.2 billion. We are flooded with impressions and news. But looking at the case of Bangladesh then and now I can’t help fearing that a further problem is that our channels of information are less capable of delivering informed and sophisticated reactions to events. Does that reflect the fact that the West is less curious and less engaged? Has the West become provincialized also in that sense?

I am sure there are serious ways of assessing those kinds of questions. I’m too over-extended right now to do anything more than to record my dismay and puzzlement and to offer in this newsletter a few things I have learned about Bangladesh in recent weeks that strike me as particularly interesting. I am going to focus on the founding crisis of the country in the late 1960s and 1970s, which is both utterly fascinating from a historical point of view and topical because it was a proposal to introduce quotas to favor descendants of veterans of 1971 that triggered the student uprising.

#1 elementary fact: One tends to assume that new nations that “break away” will be smaller in population than the states from which they split. In the Pakistani case in 1971 the reverse was the case.

The lopsided construction of Pakistan in 1947 joined together two predominantly Muslim regions of the Raj, regardless of the huge ethnic and cultural differences that divided East Pakistan (Bangladesh) from the West (modern Pakistan). It also created a strange mismatch of demography, economics and political influence. According to the 1961 census, politically dominant West Pakistan, where the military had their center of power, had a population of 42 million. At the same time, East Pakistan was estimated to have a population of 50 million. So when democratization was attempted and the Bengali Awami League established its hegemony in East Pakistan, they held the majority in the joint Pakistani parliament, a fact that both the West Pakistani military leadership and the elected leaders in West Pakistan were unwilling to concede.

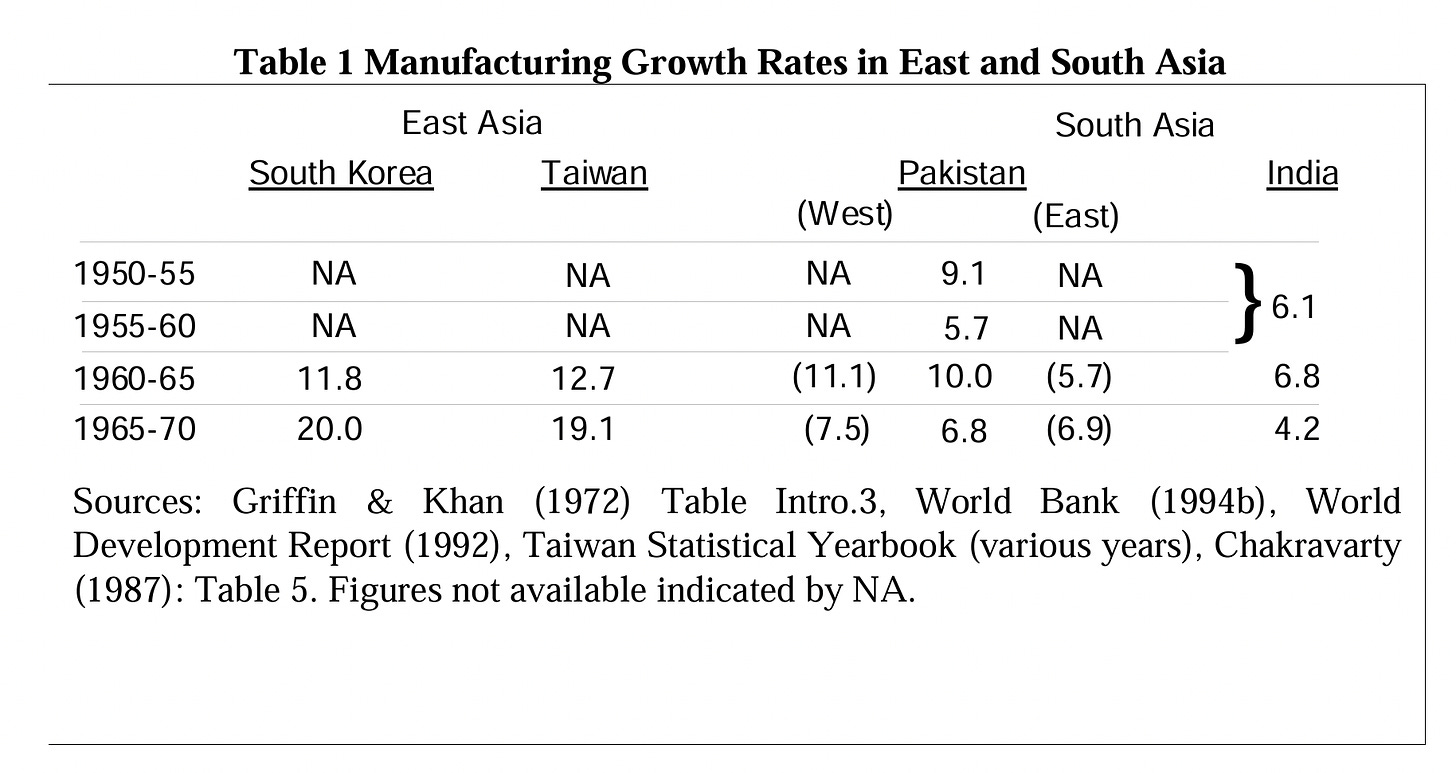

#2 Surprise: In the 1960s, under military rule, Pakistan was widely touted as highly successful growth models. This gave the East Pakistani leadership resources and authority both at home and abroad. But it also sowed seeds of division.

Under the authoritarian, modernizing leadership of General Ayub Khan (1958-1969), Pakistan was touted as one of the original “Asian tigers” . Crucially, West Pakistan accelerated far ahead of its great rival India.

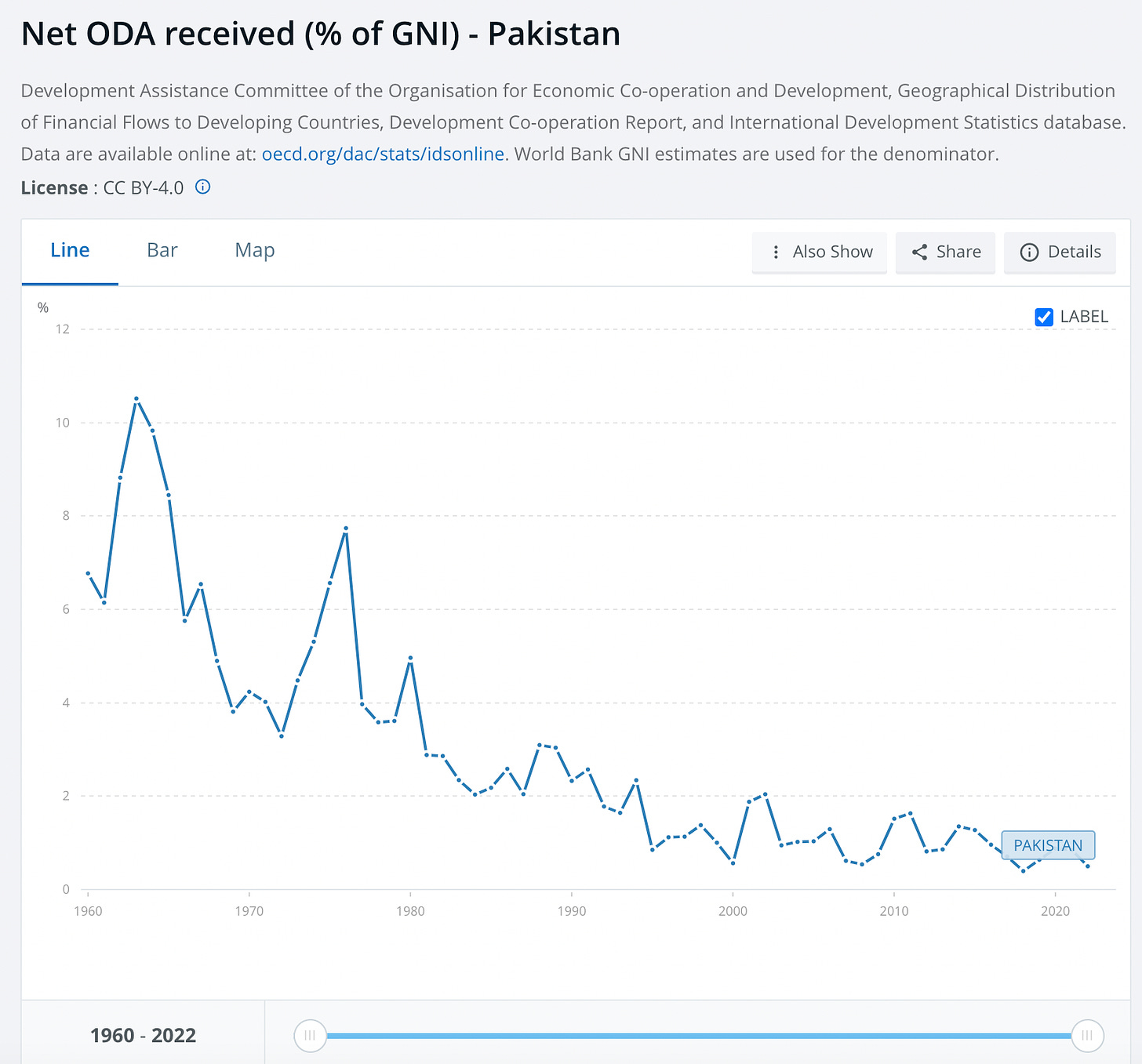

This growth was fueled by exceptionally high levels of foreign aid in the 1960s, which, as is true of aid generally, has attenuated since. Pakistan today, despite its strategic significance, its huge population and urgent needs receives far less aid as a share of GDP from a far richer world than it did in the 1960s.

Source: World Bank

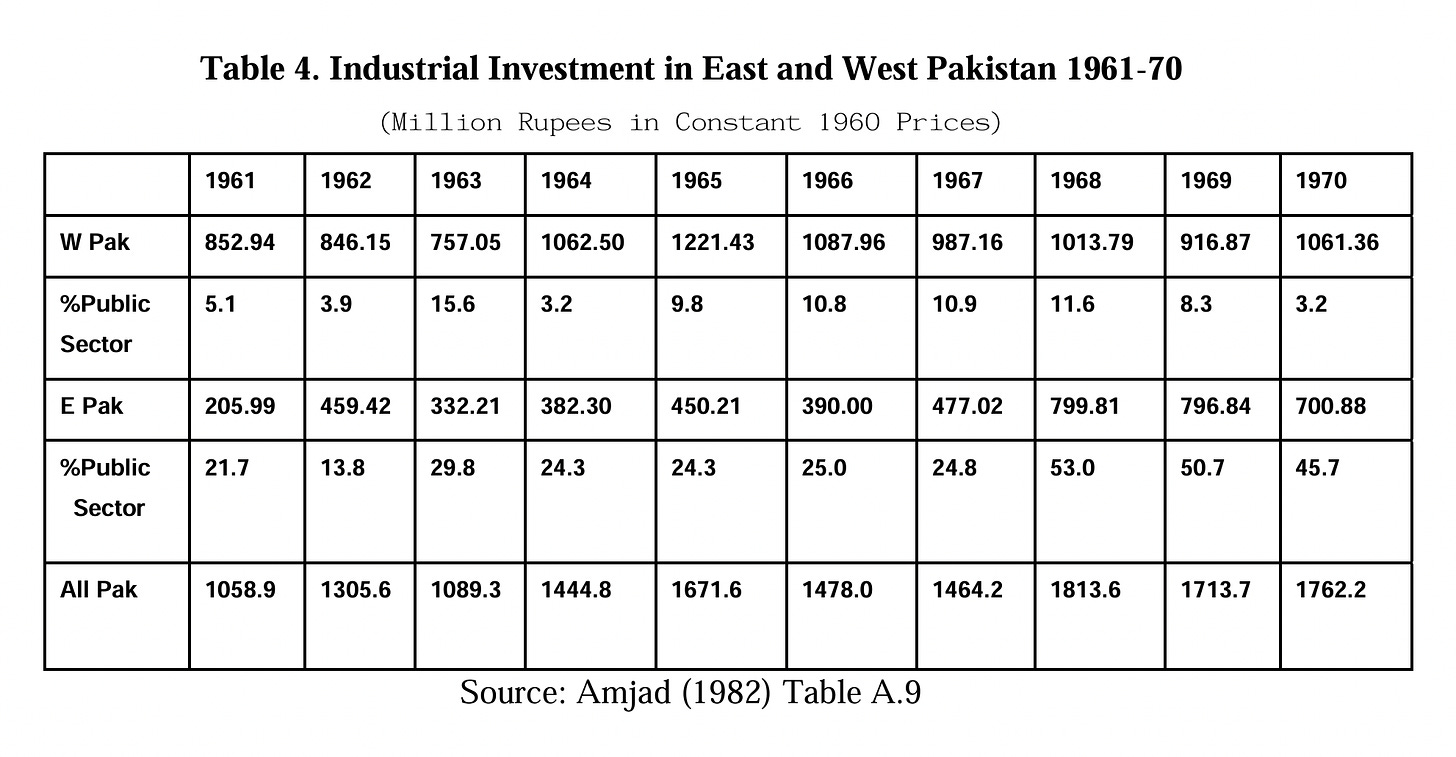

But that ultra rapid growth in the 1960s, also intensified the disparities between two parts of Pakistan, with West Pakistan seeing much larger investment and growth and East Pakistan lagging relatively speaking behind.

Source: Industrial Policy In Pakistan

This was particularly galling because the Bengali economy of East Pakistan was historically one of the region’s great export engines and its earnings continued to fill the coffers of the Pakistani state.

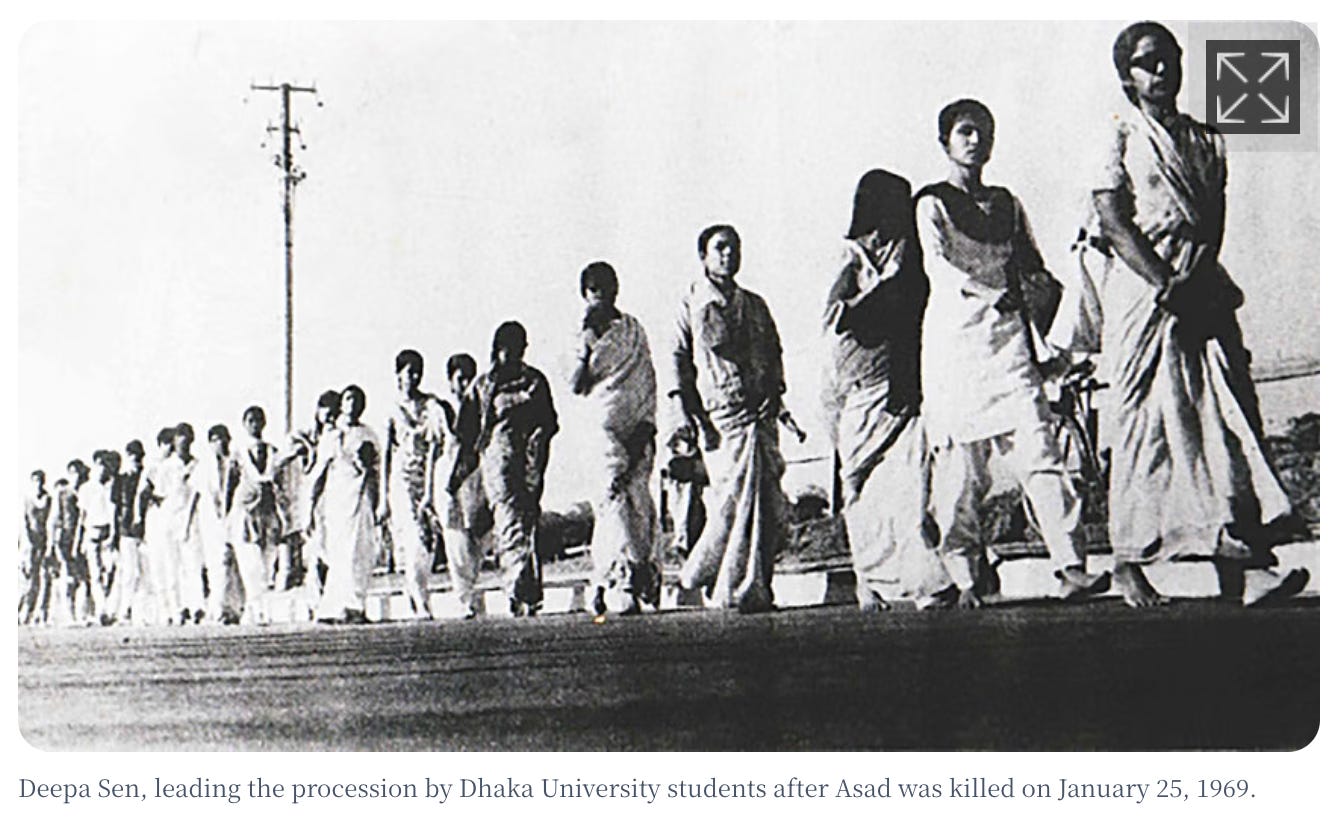

#3 Student protest was widespread across the globe in “1968”. But nowhere was it more consequential than in Bangladesh where an East Pakistani student movement, effectively challenged West Pakistani rule, setting the stage for a national uprising and the formation of an independent Bangladesh.

You would never know this from standard accounts of 1968, which focus on campuses in the West. It is a point ably made by Srinath Raghavan in his indispensable study of the global politics of 1971.

This interview is a great accompaniment to his crucial book.

There is an excellent essay by Samantha Christiansen on the culture and politics of student protest in Bangladesh which has striking echoes in the present.

In 1968, of course, students were causing headaches for government leaders far beyond Pakistan’s national borders and regional scale. While newspapers were under strict censorship and were limited in their ability to run stories about the activities of anti-government activity in Pakistan, they were free to report on the activities of students elsewhere, and they did so in high volume. In fact, in the Pakistan Observer for the year of 1968, student uprisings dominate the coverage, occupying as much attention as the Vietnam War. There was also a weekly column reporting on student political uprisings entitled “The Angry Young World” which ran articles on a variety of uprisings. The sense from reading these dailies was of a world being turned upside by youth revolt; thus, even though the papers did not have any stories regarding student activity in Pakistan, they fomented a spirit of youth political agency through reportage on other arenas, and created an international scale into which students at Dhaka University could place themselves. These newspaper stories provided the linkage of Dhaka University students with the larger “imagined community” of the youth in the Global Sixties (Anderson 1991; Zolov 1999). Of particular interest was the rising young star in the British New Left, Tariq Ali. … The brutal assassination of Asad uz Zamman, a student at Dhaka University and a well-known political activist on campus, had a profound mobilizing effect on the movement. The student community was affected deeply and personally by the death of such a popular and prominent member of the campus. A gruesome image of his dead body just after being shot, with blood pouring from the back of him was printed on the cover of virtually every newspaper the next morning, and SAC declared three days of mourning on his behalf. Students gathered the morning after the death and raised Asad's bloodied shirt onto a pole. Thousands of students gathered in mourning for their fallen comrade. Tofail Ahmad recalls, "At that day, we took an oath that Asad's death would not be in vain. He was one of us—not just a Bengali—a student of Dhaka University, truly one of us. We felt a sadness deep in our bellies" (Personal interview 2010). Asad was declared a martyr by the students. A well circulated poem for the martyred Asad, captures the mood of the students,

Like bunches of blood-red Oleander, Like flaming clouds at sunset Asad's shirt flutters In the gusty wind, in the limitless blue. To the brother's spotless shirt His sister had sown With the fine gold thread Of her heart's desire Buttons which shone like stars; How often had his ageing mother, With such tender care, Hung that shirt out to dry In her sunny courtyard. Now that self-same shirt Has deserted the mother's courtyard, Adorned by bright sunlight And the soft shadow Cast by the pomegranate tree, Now it flutters On the city's main street, On top of the belching factory chimneys, In every nook and corner Of the echoing avenues, How it flutters With no respite In the sun-scorched stretches Of our parched hearts, At every muster of conscious people Uniting in a common purpose. Our weakness, our cowardice The stain of our guilt and shame- All are hidden from the public gaze By this pitiful piece of torn raiment Asad's shirt has become Our pulsating hearts' rebellious banner.

#4 As the crisis escalated in 1971 and the Pakistani military cracked down with massive force, the mass killings directed at the political opposition but also the Hindu minority in East Pakistan, were soon described both on the spot and in the global media as a genocide and comparisons to the Holocaust were drawn.

Down to the present day, Pakistani and Bangladesh researchers and propagandists debate the question of “3 million” victims. Al Jazeera made this attempt at a summary in the context of war crimes trials staged by Sheikh Hasina’s regime in the 2010s.

What is beyond question is that there was a vast and deliberate massacre. This resulted in a gigantic refugee exodus to India. It was seen as a matter of international concern that went beyond questions of internal affairs and national sovereignty. And it attracted worldwide attention on that basis.

Thanks to the archive of Youtube, fifty years later, we can watch both original TV reports, concerns and engaged poetry from the period, which give a vivid impression of how the crisis was seen in living rooms around the world.

As amongst news reporting from 1971 on youtube two have so far stood out for me: This comprehensive report by Dateline Bangladesh on Youtube I am using this awkward link because the content is truly graphic and Youtube won’t permit a direct link.

This ITN compilation gives an eye-opening insight into post-colonial British coverage.

#5 The role of the Nixon administration and Kissinger in particular has been widely discussed. The protests to Washington by the staff at the US Consulate in Dhaka at the violence they were witnessing went unacknowledged. It was to be a formative moment for ethical discourse within the US foreign service. Gary Bass’s book is a vital reminder of all this.

But apart from its callousness. The singularity of US policy is brought out even more clearly by Raghavan’s comparative global treatment of the crisis, which shows how the US was the only major global player whose diplomacy ignored the regional context of the Bangladesh crisis and reduced it, to the exclusion of all else, to a brutal Cold War logic of my enemy’s enemy. What Washington was interested in, to the exclusion of all else, was using Pakistan as a conduit to Beijing, with a view to outplaying the Soviet Union. Ironically, on Raghavan’s reading both the Soviet Union and China took a more sophisticated view of the crisis. The subversive implication is that Kissingerian realism was not just ethically barbarous. In its reduction of the crisis to a logic of simple geopolitics, it was not so much realistic as simply crude and one-dimensional.

#6 The indignation in the West at the scale of the massacres in Bangladesh and Western complicity in them, sparked a truly dramatic mobilization of pop culture.

This was more short-lived than the mobilization around the civil rights movement and Vietnam. But in the reach of its global imagination the mobilization for Bangladesh in 1971 was impressive and still stirs a chord. This report on the famous Concert for Bangladesh headlined by George Harrison and Ravi Shankar in Maddison Square Garden, is remarkable viewing.

Joan Baez did a beautiful tribute for Bangladesh in her own quieter style. For those with a strong stomach you may also wish to savor Allen Ginsberg’s memorial to the refugee treks on Jessore Road.

What is striking about these contributions is not necessarily their artistic quality, but three things. The strong sense of global engagement. Secondly, the insistence on the rhetoric of “millions” to convey the sheer scale of the violence and the exodus and the association with the Holocaust. And finally, the sense of excitement and novelty you hear in people’s voices as they pronounce the name of a new nation - Bangladesh. As Wikipedia explains, it is a typical creation of modern nationalism conjuring ancient roots.

The etymology of Bangladesh ("Bengali country") can be traced to the early 20th century, when Bengali patriotic songs, such as Aaji Bangladesher Hridoy by Rabindranath Tagore and Namo Namo Namo Bangladesh Momo by Kazi Nazrul Islam, used the term in 1905 and 1932 respectively.[26] Starting in the 1950s, Bengali nationalists used the term in political rallies in East Pakistan.

#7 Following independence, the new nation of Bangladesh was born into intense crisis. It was massively dependent on India, which did not hesitate to exploits its new leverage. Amidst the oil price and food price shocks of the early 1970s, Bangladesh was one of the weakest links. It suffered an accelerating inflation in 1972-3, which issued into a full blown famine in 1974. This too left deep marks on national politics and the Bangladeshi development model.

Bangladesh from the 1980s onwards would become one of the key laboratories for new forms of development finance, notably in the form of the Grameen bank and its model of microfinance. This fascinating book by Naomi Hossain argues that this Bangladeshi success story is rooted in the traumatic shocks that accompanied the birth of the new state in the early 1970s.

From an unpromising start as ‘the basket case’ to present-day plaudits for its human development achievements, Bangladesh plays an ideological role in the contemporary world order, offering proof that the neo-liberal development model works under the most testing conditions. How were such rapid gains possible in a context of chronically weak governance? The Aid Lab subjects this so-called ‘Bangladesh paradox’ to close scrutiny, evaluating public policies and their outcomes for poverty and development since Bangladesh’s independence in 1971. Countering received wisdom that its gains owe to an early shift to market-oriented economic reform, it argues that a binding political settlement, a social contract to protect against the crises of subsistence and survival, united the elite, the masses, and their aid donors in the wake of the devastating famine of 1974. This laid resilient foundations for human development, fostering a focus on the poorest and most precarious, and in particular on the concerns of women. In chapters examining the environmental, political, and socioeconomic crisis of the 1970s, the book shows how the lessons of the famine led to a robustly pro-poor growth and social policy agenda, empowering the Bangladeshi state and its non-governmental organizations to protect and enable its population to thrive in its engagements in the global economy. Now a middle-income country, Bangladesh’s role as the world’s laboratory for aided development has generated lessons well beyond its borders, and Bangladesh continues to carve a pioneering pathway through the risks of global economic integration and climate change.

There is no neat conclusion to this list of points. I simply hope that it is useful and that I find the time, energy and headspace to keep adding to it.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

Thankyou for this informative summary! I confess my ignorance of this country's development, and am grateful that you have taken the time to write this report.

Keep in mind that turning Bangladesh into Pakistan 2.0 suits the West just fine.