Chartbook 313 Being realistic in the polycrisis? Or, does the West/global North know what time it is?

Being, thinking and acting in “medias res” is not a liberal evasion of a deeper truth that would be revealed if one ascended to a supposedly superior vantage point. It is not even a choice. Being, thinking and acting in medias res is at one and the same time fate and achievement. What is evasive or self-deluding is not to reckon with this condition.

Whatever certain intellectualisms, Marxist and otherwise, may suggest, we cannot escape our thrownness. And on the other hand, actually being in touch with and in relation to a world of polycrisis, encompassing the scale, complexity, tensions, contradictions and pace of the modern world, both inside and outside ourselves, close up and far away, is an immense and often overwhelming challenge from which bits of ourselves continuously retreat and take flight.

The challenge of actually being in medias res as fully as possible, is what preoccupies me in recent books, shorter writing, this newsletter and the podcast.

More simply this challenge can also be formulated in a series of snappy questions: Where are we? Do we know what planet we are actually on? Can we come back down to earth? Who is “we”? And, most urgently, the classic refrain: “What time is it?” Do we know, do we really know how fast the clock is ticking and where we are on the timeline of history?

These questions are not contemplative. They are not posed out of idle curiosity. They are urgent and practical. They are the first step, if we want to claim to be realistically engaged with the world as it is and thus to have any hope of informed and purposive agency. Conversely, flights from reality, blindspots and structural hypocrisies are profoundly telling as to our actual interests and willingness to summon the will, the power and the resources to act effectively in the world we are actually in.

In this spirit, in my FT column I’ve repeatedly harped on questions of global development as particularly glaring examples of the way in which Western governments and their publics fail to rise to the scale of contemporary global challenges.

In previous one column I addressed the failure of rich countries to seize the huge opportunity of investing at scale in global public health

In a world of polycrisis, in which intersecting problems compound each other and there are few easy wins, it is all the more important to recognise those policy choices that are truly obvious. Vaccines are one such investment. Since the 1960s, global vaccination campaigns have eradicated smallpox, suppressed polio and contained measles. Modest expenditures on public health have saved tens of millions of lives, reduced morbidity and allowed children around the world to develop into adults capable of living healthy and productive lives. … Unfortunately, in public policy, pandemic preparedness is all too often relegated to the cash-starved budgets of development agencies or squeezed into strained health budgets. Where such spending properly belongs is under the flag of industrial policy and national security. Biotech is one of the most promising areas of future economic growth, combining research, high-tech manufacturing and service sector work. As the IMF declared: “vaccine policy is economic policy.” And pandemic preparedness belongs under national security because there is no more serious threat to a population. A far larger percentage of the UK died of Covid between 2020 and 2023 (225,000 out of 67mn) than were killed by German bombs in the second world war (70,000 out of 50mn). The annual defence budget of just one of the larger European countries would suffice to pay for a comprehensive global pandemic preparedness programme. The money lavished on just one of the UK’s vainglorious aircraft carriers was enough to have made the world safe against both the ghastly Ebola and Marburg viruses.

In 2023, I highlighted the perversity of the USA and EU fretting about their loss of influence in the Sahel when their aid effort was so derisory.

After last week’s Brics meeting in South Africa, the question hangs in the air: what does the west have to offer a new, multipolar world? Nowhere is that question more urgent than in Africa. The Niger coup extends the comprehensive rout of western strategy across the Sahel. The debacle of western military intervention, notably on the part of the French, is embarrassing. But the wave of coups also represents a failure of Europe’s effort to link economic development and security in the programme known as the Sahel Alliance. This multinational group jointly promoted by France and Germany co-ordinated aid and development projects across the region. Launched in July 2017, as of 2023 it counts more than 1,100 projects with a cumulative funding commitment of €22.97bn. For Niger, project commitments under the Sahel Alliance come to over €5.8bn. And this is only a part of the financial assistance that Niger was receiving in the years prior to the coup. According to OECD data, the combined total of official development assistance for Niger in 2021 came to $1.78bn. These numbers sound impressive until you place them in relation to the scale of the Sahel’s development needs. The western Sahel is home to 100mn of some of the poorest people on Earth. Niger’s population of 25mn has the third-lowest human development index in the world and the highest birth rate. Long hailed as the western bastion in the region, almost two-thirds of the population cannot read. Niger desperately needs investment in education, irrigation and basic health services. To meet these priorities, on a per capita basis foreign aid in 2021 came to just $71 for every inhabitant of Niger, or $1.37 per week. Of this miserly total, roughly 7 cents were spent on education, 15 cents on health, and 30 cents on production and infrastructure. Twenty-six cents were devoted to the basics of keeping alive.

Last month I took up the issue of the prevailing fatalism in the USA when it comes to the question of development in Central America

The attack line from the Republicans is predictable: Kamala Harris was Biden’s border tsar. The crisis on the border with Mexico shows that she failed. So too is the response from the Democrats: No, the vice-president never was in charge of the border. Her role was to address the root causes of migration from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. No one can blame her for failing. It was mission impossible. The striking thing about this retort is not that it is unreasonable, but that it sets such a low bar. Whereas for the Republicans the desperation in Central America is reason to seal the border even more firmly, for the Democrats the deep-seated nature of those problems is an excuse. Apparently, no one expects Harris or anyone else to succeed in addressing the poverty and insecurity in the region. Shrugging its shoulders, the US settles down to live with polycrisis on its doorstep.

This weekend, as context for the previous piece on US policy in its neighborhood, I returned to the question of the scale of global aid and European aid in particular for the African continent.

Again it is the undersized reaction of the rich world to contemporary global challenges that is front and center.

Uncontentious estimates of global development need put the sum of investment required to achieve comprehensive sustainable develoment at between $ 3 and 4 trillion per annum. That is an immense amount, but given the rewards on offer and the fact that global GDP stands at $105 trillion it cannot be dismissed out of hand as “utopian”.

FDI and private lending will do some of the work. But it is highly volatile and not willing to take the risks necessary for comprehensive development. So support and derisking, on carefully managed terms, must come from public balance sheets. Some will come from multilateral development banks like the World Bank. But a substantial amount will depend on concessional loans and aid in the form of grants. The crucial question is, how much is being made available? How far does it reflect the needs of the moment?

Answering that question requires wrapping ones head around the alphabet soup of aid programs and various channels of financial assistance. That is a daunting task. Plunge into an overview of EU development policy like that ably put together by Mikaela Gavas and W. Gyude Moore and you find yourself wading through layer upon layer of acronyms, programs, initiatives, facilities and agendas. Welcome to the experience of being thrown head first into the midst of things.

Seeking for some means of quantitative summary and some point of comparison with the aid programs of USAID and the US State Department, I turned to the comparative data compiled by the OECD on the aid effort of members of Development Assistance Committee (DAC). These are the data by which national governments in the rich wold tend to benchmark their aid efforts. They are a gift to anyone wanting to orientate themselves in the here and now. And they provide a clear and unambiguous answer to our question.

Rich-country financial assistance for the developing world falls far short of what might be needed to address the most urgent needs of the moment and to support a comprehensive investment in sustainable development.

According to the OECD, the volume of official development assistance (ODA) in 2023 was 224 billion, a new high. Of that amount only $36 billion went to Africa, the continent with the most dramatic development needs.

Of course, money is not everything. it takes more than aid and concessional funding to dramatically accelerate economic development. But to dismiss the issue of funding is in bad faith. Africa needs capital and assistance and $36 billion spread across the entire giant continent of 1.4 billion people is a pittance.

So, what might these figures look like, if the West was actually invested in changing the trajectory of Africa’s development through material assistance? To this question, too the OECD data provide an answer.

Incongruously, but also revealing, alongside aid for Africa, Asia and the rest of the developing and low-income world, the OECD data include aid and concessional funding provided by Europe, the US and other rich countries, for Ukraine.

The upshot is startling: In 2023 money flows to Ukraine classified by the OECD as official development assistance (ODA) exceeded the equivalent flows to the entire African continent.

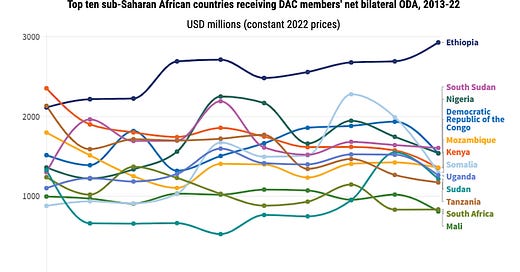

Obviously, Ukraine is a country at war. But even bloodier and disastrous conflicts have convulsed Ethiopia and Sudan in recent years without any commensurate Western engagement.

At this moment, millions in Sudan are at risk of outright famine. The UN’s funding appeal for Sudan famine relief is for $2.6 billion, less than the monthly rate of support for Ukraine in 2023. So far it has raised $1 billion.

This is a stark measure of the difference between a crisis in which the Western donors see their interests directly and urgently engaged and one to which they are relatively indifferent.

It is the difference between a crisis happening to “people just like us”, people who have been welcomed in their millions into their neighboring European countries, and a crisis happening in Africa to black people with whom the donor populations feel on the whole only an abstract form of sympathy and identification.

It is the difference between crises happening on either side of the global colour line.

These discrepancies reveal the extraordinary extent to which, for all the common place talk of globalization, racial hierarchies and geographical division continue to undergird our political discourse and policy. They are a sad commentary on where we are at and what time we are in. They also force the question of whether and by what means this line will be maintained and at what cost.

Surely there is a large component of "racism" in the disparity of funding between Ukraine and Africa. It is of course natural to fund the needs of those who are easily relatable to you over those who seem to be very different from you. It is also true that funding Ukraine against Russia serves a self defensive purpose, helping keep Russia at bay from inflicting violence on the donors themselves. In addition, the scale of need in Africa and the Sahel is so great, and the necessary systems and infrastructure on the ground are weak or non-existent making investment less effective and less likely. What would the money actually do, would it stand up systems of democracy and lift people out of poverty, or be co-opted by the corrupt existing powers? As in Haiti, the needs are great, but the political infrastructure is not in place to use the donations in a manner consistent with the intent of the donors. So, it makes sense that nations with money send more money to those who are more relatable to them, and more likely to use the money wisely, in the eyes of the donor class. Political reform is a precondition for increasing donor activity. Perhaps donations above feeding/medical programs meant to keep people alive and reduce misery need to go to education and political development.

I enjoyed this very much. Realistic, without being fatalistic.

"Again it is the undersized reaction of the rich world to contemporary global challenges that is front and center.Uncontentious estimates of global development need put the sum of investment required to achieve comprehensive sustainable develoment at between $ 3 and 4 trillion per annum. That is an immense amount, but given the rewards on offer and the fact that global GDP stands at $105 trillion it cannot be dismissed out of hand as “utopian”. "

While it's hard to discuss a 'polycrisis' with sunshine/rainbows. How about the mindset sets a more diligent, stubborn, tenacious tone? Even naive from time to time because even the effort gives young people some measure of hope in making the human capital investments as well.

As far as developmental banks & the west. That is a long overdue discussion. The idea of debt peonage is so profoundly patronizing to me. Capital flight from crisis ridden, corrupt nations to western nations is not only the fault of the west. We are all people with agency. What it clearly shows is that funds are being misappropriated and stolen from the people of a nation and held abroad. The paper trails exist. There should be a legal arm of the UN for financial crimes which are a precursor often for local suppression. Sometimes the ill-gotten gains are a product of it. All tied into a ball.

Multilateral banks have the fiduciary duty not to launder money from criminal enterprises. And a global body should be able to legally reappropriate back into the Treasury of a nation. There are global issue. Fraud is rampant against US citizens as well. And I'm not playing into the bankers are all criminals paradigm. I just think a reforming of institutions needs to be on the table and discussed at the UN if globalization and collective well being is still on the table. Unless sustainable developmental goals are now lip service.