Why did American financial hegemony have a deflationary bias, both in the interwar period and in the 1980s? Why do policy-makers not run the economy hot all the time? If modern economics and the practice of modern economic government give us the policy tools, why not push at all times for high employment, high investment, high growth?

One answer is that the question is based on naive premises. Economies are complex and subject to violent shocks and fluctuations. Policy is difficult. If the economy is not in a full employment high-growth regime at all the time, that it is not for want of trying. It is difficult to do. It takes skill and luck.

In the interwar period, where this series of hegemony notes begins, that is an important part of the answer. The Fed was inexperienced. 1920 was the first time it had ever hiked interest rates. No one knew how the system would react.

The other school of answers starts from the premise that the interpretation in terms of “policy failures” is itself naive. The reason that the economy is not kept humming at all times, is that though high-growth and full employment may sound optimal from a societal point of view, though it might win accolades from Keynesians, it is not actually in the interest of powerful groups in society.

The naivety lies in imagining that there is an underlying harmony of societal interests that just needs to be discovered and revealed by smart policy. In fact, when it comes to the important parameters of economic policy, antagonism is irreducible. In this sense, “policy failure” is not a bug; it is a feature of the system.

The best known of these interpretations is that developed in the 1930s by Polish Marxist economist Michał Kalecki. He focused on the capital-labour relation to explain the haphazard way in which progressive Keynesian policy was summoned to power and then dismissed. This followed from the class logic by which at moments of depression even the most die-hard conservative business interests could see the attraction of vigorous state action to stimulate demand and restore profit. That is eventually what transpired in the US, in Germany and in the UK in the 1930s. But, as full employment returned, running the economy hot loses its appeal. Strong demand and a tight labour market shifts the balance of power in favor of labour. This made itself felt both in wage bargaining and on the factory floor. Kalecki predicted that at that point, as the balance tipped, the era of “open-mindedness”, in which “good” Keynesian policy was espoused, would give way to a new phase in which propagandists for capital demanded austerity in the interests of “restoring confidence”. If they did not get their way, a “capital strike” would result in the cancellation of investment and a fall of aggregate demand. Class interests would drive a “cooling off” and a recession.

Historically speaking, since the advent of the modern economic policy era in 1945, some version of this logic has played out repeatedly.

But, in the 19th century and in the aftermath of World War I a rather different and more direct logic of class power was in play. If we ask who apart from employers might benefit from austerity and deflation and if we shift our focus from the labour market to the financial markets, the answer is clear. Fixed interest bond-holders, i.e. holders of debts owed by government or businesses, have a pronounced and clear-cut interest in the prevention of inflation. Rising prices that go hand in hand with a booming economy erode the real value of these assets. In a deflation, by contrast, bonds gain in value along with all other monetary assets. In modern economic history, the flipside of the great recessionary episodes are strong periods of real returns for bondholders.

This logic is obvious in the abstract. But its sheer scale is not often appreciated. This makes the data for long-run financial returns published by a team of economists from the London Business School and University of Cambridge in the UBS Investment Return Yearbook so interesting.

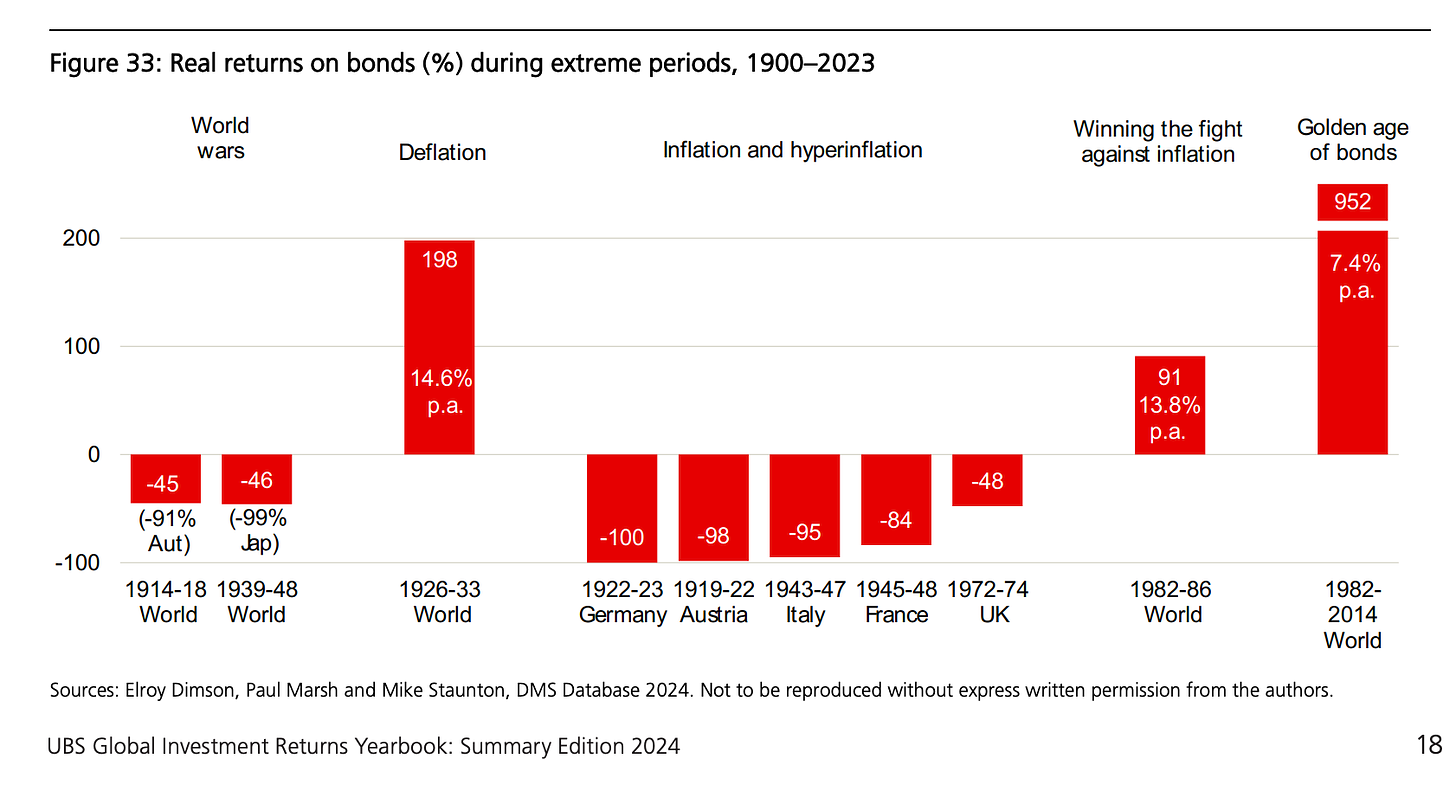

Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton confirm that inflationary periods, such as those after World War I, World War II and in the 1970s were ruinous for bond holders. But, then, look at the flipside!

Copyright © 2024 Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton

The very best times for bondholders have been in recent decades. On the right-hand side you see the huge gains made by bondholders in the era of the “great moderation” that followed Volcker’s interest rate shock in 1979.

And then cast your eye back to the interwar period, the origin of the modern era of US hegemony, to see what was at stake for bondholders in the deflations of the 1920s and 1930s. Look at the years between 1926 and 1933. This is an era that for good reason is remembered as a disaster of economic policy, a period of mass unemployment bankruptcy and state crisis. But it was nothing short of excellent for bondholders. If you bought the right kind of bonds - an important qualification - you made outsized gains in real terms, 14.6% pa, even as global capitalism suffered the worst crisis in its history.

If you want to understand why there was such a powerful deflationary bias in monetary and fiscal policy in the leading financial centers in the US and Britain after World War I, this is the key. Bond holder interests prevailed.

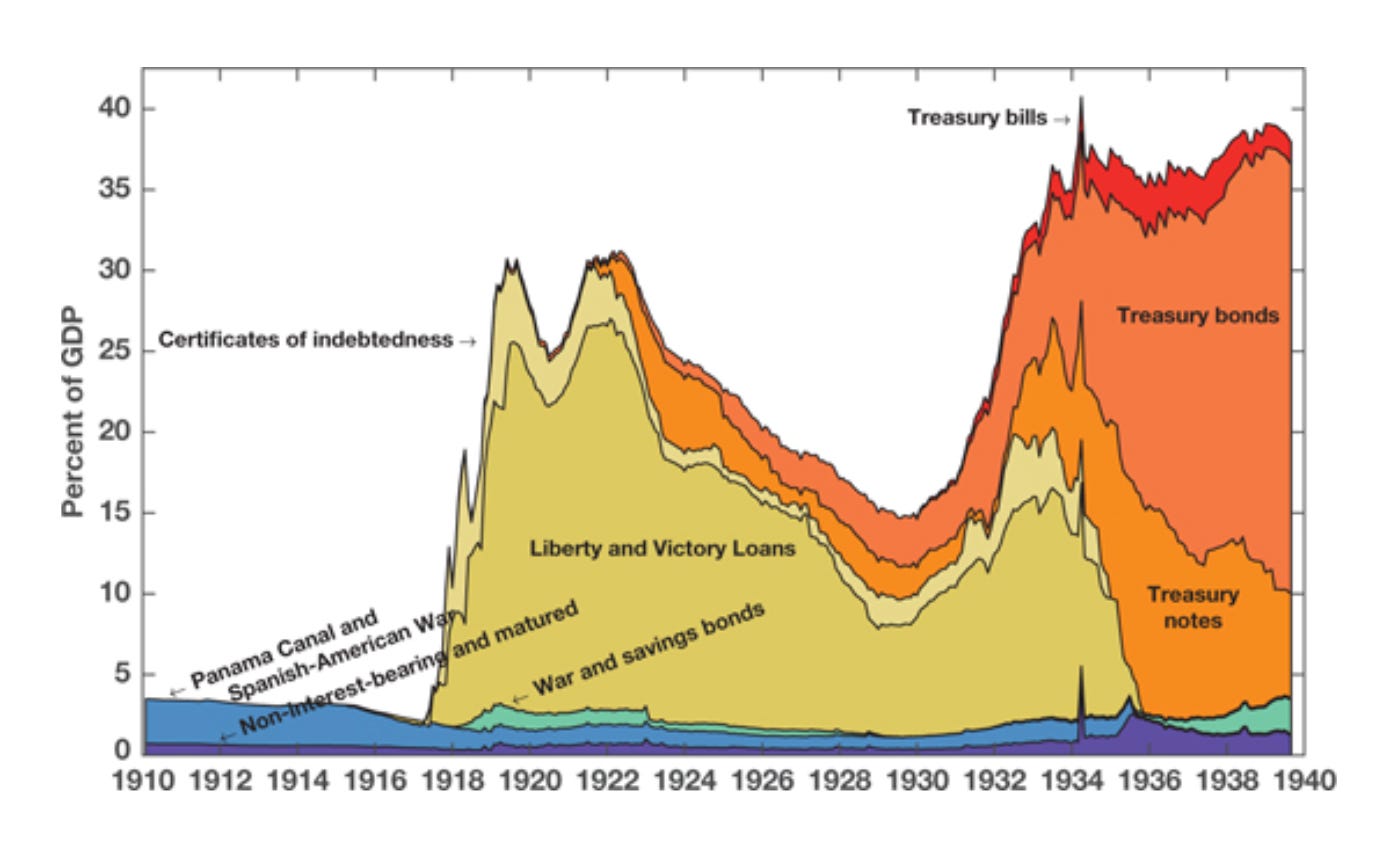

If bond holders were a small group and their investments were a merely private matter, their concerns would not have weighed heavily in the balance. But the opposite was the case. After World War I, the volume of debt held by the investing public across the rich countries of the world was unprecedented. Those able to contribute the most to wartime finance were by definition amongst the most wealthy and influential classes, but war bonds had also been spread across an unprecedentedly wide group of savers. And buying these bonds was not merely a matter of private concern. Bond drives were the financial bedrock of the patriotic war effort. In the postwar period, bondholders were thus a key constituency in every respect.

Private holders of US Treasury debt as a share of US GDP:

Source: Hall 2019

On the defeated side, in Germany and Austria, as the data show, bondholders would face total loss. The open question was how the bond holders in the victorious powers would fare.

The doubling of the price level since 1914 even in the United States ate deep into the real value of the war bonds. The question once the shooting stopped was whether the postwar price level would be accepted as a de facto status quo. In that case the bond holders would suffer an irretrievable loss. If, instead, the authorities pushed through a deflation, at least a portion of the real value of the bonds would be restored.

This was the cardinal question of financial policy in the United States and it was therefore also the key question for London. After 1918 the United States set the benchmark. The key priority for London was to ensure that anyone who lent money to Britain during World War I in pounds sterling, did no worse than if they had lent in dollars to the US government.

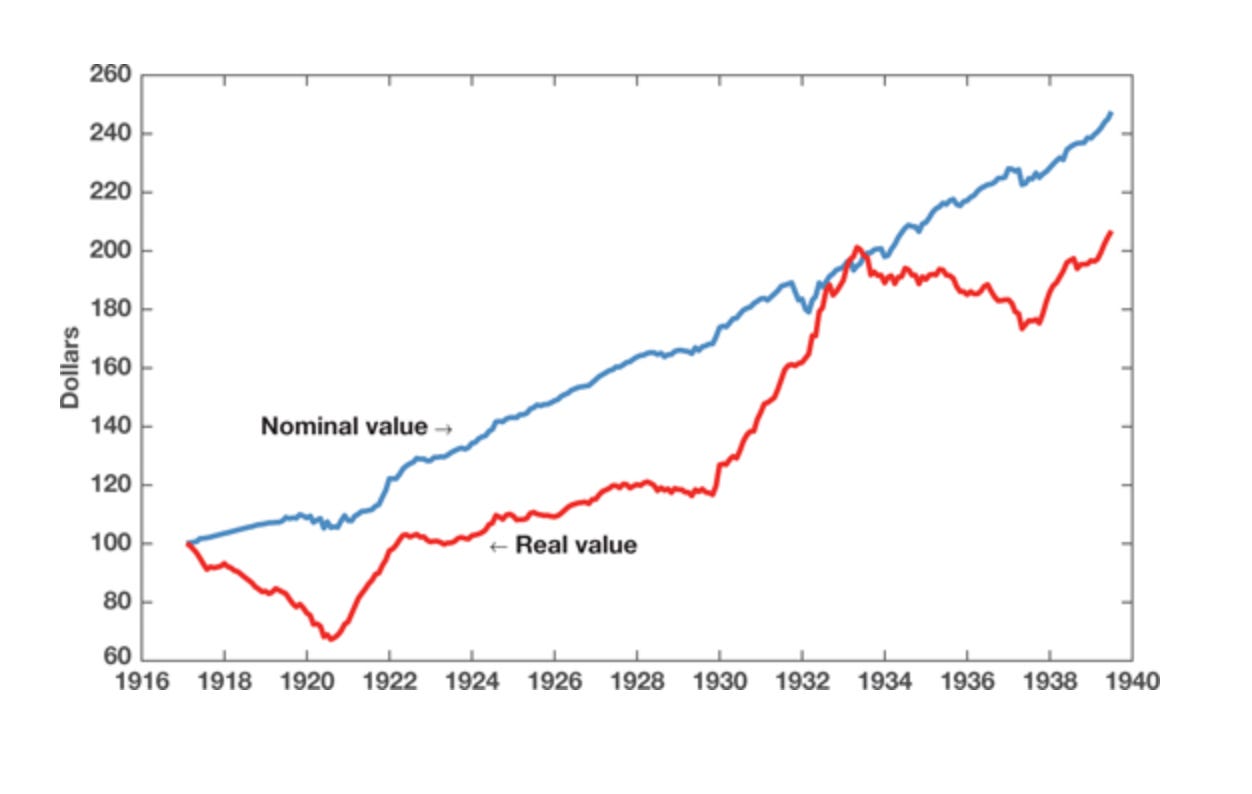

The answer given by the US authorities is neatly displayed by this graph from Hall 2019.

Nominal and Real Values of $100 Invested in January 1917 in US Treasury’s Bond Portfolio

This is the flipside of teh inflation-deflation story which I have been telling in these notes.

The graph shows the value of $100 dollars invested in 1917 in a portfolio of Treasury securities with the interest reinvested in the portfolio. The blue line is the nominal value. The red line shows the real value once discounted by inflation. The gap between the two lines shows the severe hit to the real value of the bond portfolio delivered by the wartime inflation between 1917-1920. By the end of 1920, though they had lent to the supreme financial power of the postwar period, investors in US bonds had suffered a 30 percent loss.

Deflation reversed that. In the years after 1920 we see the payoff to bondholders from the deflationary turn in policy. As the Fed and the Treasury tipped the US into recession in 1920s, the real value of the portfolio began to recover. By 1923 it had returned to its value in 1917, not allowing for interest. Thereafter, the gap began to widen again as a result of the moderate inflation of the 1920s. The truly spectacular recovery in the real value of the portfolio began in 1930 with the Great Depression. As the US entered a crushing deflation and price plunged, the real value of the war bonds recovered strongly. By 1934, thanks to the deflations of 1920-1922 and 1929-1933 the gap between real and nominal values was entirely closed.

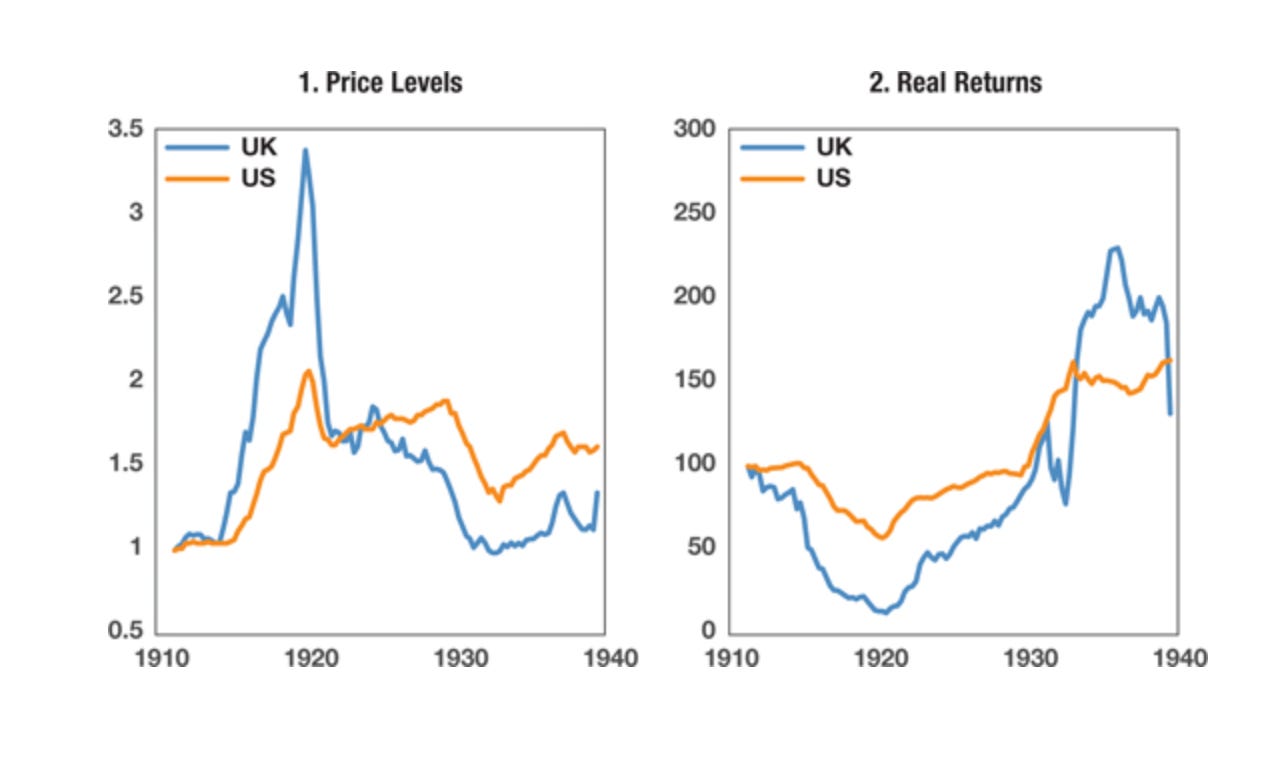

As I argued in the previous note in this series, the decision of the US authorities not to accept the postwar price level of 1920 as a status quo and, instead, to impose a deflation put huge pressure on the rest of the world economy. Many, like the Italians or French were forced to accept stabilization at a significantly depreciated level, with large losses to wartime bond holders. The Franc returned to gold eventually at one fifth its prewar value. The UK authorities by contrast were determined to hold the line. Ignoring Keynes’s repeated urgings to opt for stabilization rather than parity with the dollar and dollar-investments, UK policy chased that of the US.

By 1920, the gap to be closed between the UK and the US was large. Whereas US prices had merely doubled during the war, in the UK they had more than tripled. The real returns on an investment in UK bonds made in the prewar years were disastrously bad by comparison with those in US bonds. In 1920, of course, US investors were sitting on losses too, but UK investors were much worse off. Once the US embarked on deflation, the direction of UK policy was clear. Close the gap!

Source: Elison 2019

As we saw in the last note, after 1920 the UK deflation was even more severe than that in the US. As a result, by 1925 the UK was in a position to return to the gold standard at the prewar parity with the United States. The pain for the real economy was enormous. The pressure on export sectors like the coal industry was such that it triggered the General Strike of 1926. But investors in UK government bonds, the pillar of UK state finances, and thus the British Empire saw their real returns rapidly converge with those of US bond investors. By the end of the interwar period, London was able to boast that an investor in UK government bonds was in no way worse off than an investor in US bonds over the same period.

Today it is the US Treasury market that is the anchor of what we know as the dollar system. The US Treasury market has evolved dramatically over the last century. But it was in the monetary and financial policy of the 1920s directed towards that market. that the full force of dollar dominance first made itself felt, in driving a deflationary course that set the terms for the entire world economy.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of the newsletter. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

I keep those rates as low as substack allows, to ensure that backing Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month.

It really isn’t much. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.

Terrific piece! I'm a (retired) mathy-quanty economist w/ a long interest on economic history & history of economics & i've never before run accross such a clear & convincing account of this dynamic.

Loving the "hegemony notes", hope they end up as a book!

But the lie, Adam, is that capital is only available with the blessing of rich people. The state can provide all the capital necessary to ensure full employment -- that it doesn't merely reveals that it is captured by rich people.