Chartbook 301 Liberty Loans: the Great War & the making of the hegemony problem (Hegemony notes 3)

In the heat of the 2024 US Presidential election campaign, American debates about economic policy have taken a weird detour into history. Donald Trump has put President McKinley the “tariff king” back on the agenda of American public debate.

William McKinley made this country rich. He was the most underrated president. And those that followed him took the money. Roosevelt took the money and built, you know, the whole thing with the parks and the dams. But McKinley made the money and he was truly the tariff king.

The choice of Vance as VP has raised the specter of “isolationism”.

Against this caricature of Republican economic policy history, Democrats instinctively position the narrative of American leadership which they trace back to FDR’s New Deal administration of the 1930s and 1940s. FDR rebalanced America’s domestic political economy, began the process of trade liberalization based on reciprocal free trade and committed the US to a policy of globalism.

It is characteristic of US political discourse that it has a long memory. But if we want to understand the mechanisms that once constituted American hegemony it actually does makes sense to look back to the early 20th century. It was at that moment that America’s economic power first came to dominate world affairs. The first decisive moment, however, was not the 1890s or the 1930s, but the years around World War I. And as I will expand in several hegemony notes, the story is strange, dominated by improvisation and punctuated crisis.

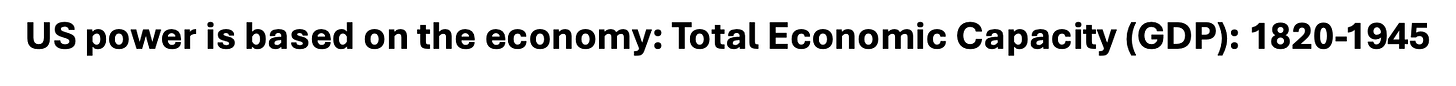

It is hard to exaggerate how far from the heart of world power the United States was in the late 19th century. The British Empire, the great world power of the 19th century, did not see fit to promote its Legation in Washington DC to the rank of a full embassy until 1893. America was only then beginning to emerge on the world stage as a player in the game of imperialist competition. America participated in the suppression of the Boxed rebellion in China. US cavalry cantered along the Great Wall. Teddy Roosevelt displayed American naval power to the world by sending the so-called Great White Fleet on a tour of friendly harbors between December 1907 and February 1909. But when the chips were really down, in the frantic diplomacy to save the Europe from war in the July days of 1914, one searches in vain for any mention of the United States. What thrust the United States to the center of global power was the European failure to contain the war. That gave a new significance to the realities captured in the graph below.

Source: Maddison Project PPP GDP data

In 1916, according to our best retrospective estimates of purchasing-power adjusted GDP, the output of the US economy overtook the combined production of the British Empire. GDP, national income and value added were all statistical measures that were only just coming into use in the first decades of the 20th century. They are seductively simple, but also potentially misleading indicators of raw economic power.

The complex we know as “the economy” can weigh in the balance in a variety of different ways. Finance, industrial and agricultural production, supplies of raw materials & energy and technological capacity are all different ways that “the economy” can matter. And the significance of any of these factors is not a transhistorical given.

America moved to the center of world affairs after 1914, because the Europeans had unleashed the largest war in history to date and they failed to end it, either by military or diplomatic means. It was the stalemate in Europe that made the United States into a decisive factor in imperialist competition. This would not have been the case if the war had concluded, as many hoped, by the end of 1914. It was the fact that European military doctrine and technique failed to yield a result that turned the war into a battle of material. America’s finances, its manufacturing capacity and raw materials - not at this time its military technology where Europe was still superior - offered a decisive advantage to those that could mobilize them. Who would mobilize America’s resources and on what terms was the key question.

That in turn raised the question of the American government, its state machinery centered on Washington DC and its relations with powerful economic interests spread out across the United States. These were highly political issues, concentrated in the figure of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson and his fraught relations with the Entente powers (The British Empire, the French Empire and Imperial Russia).

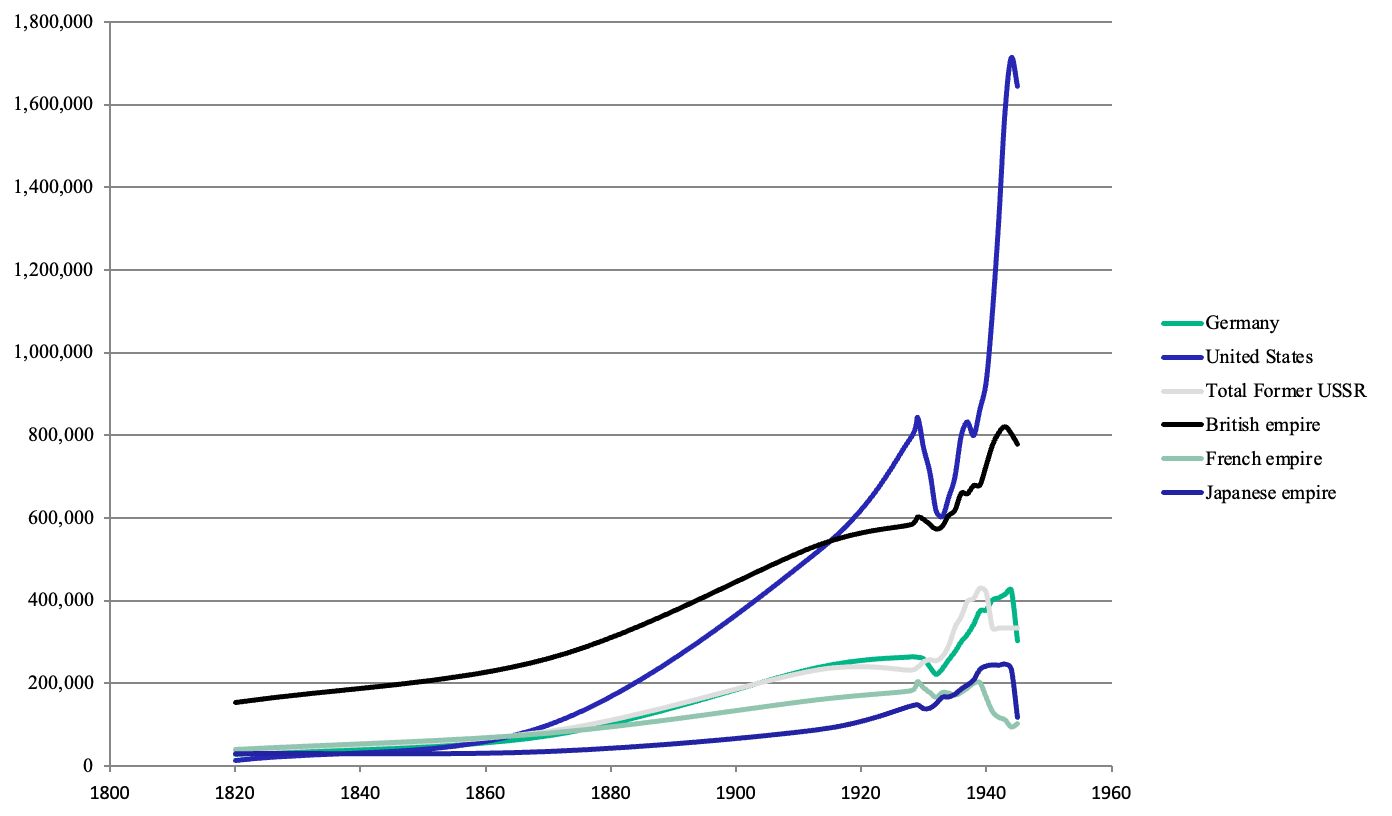

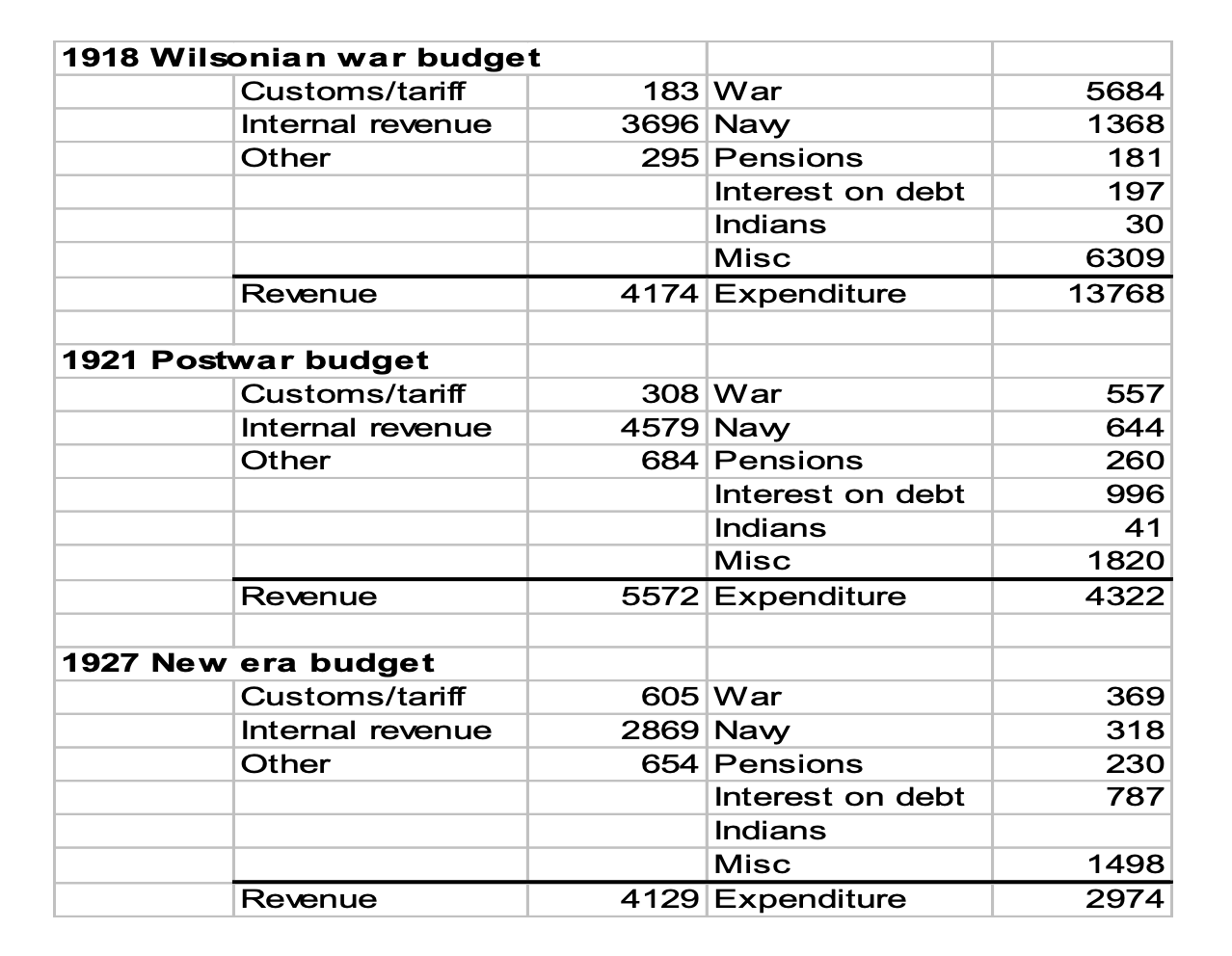

Woodrow Wilson is widely known as the advocate of a (highly racialized) vision of liberal world order. His agenda of domestic political economy known by the label of the New Freedom is less often appreciated. In the few years before the outbreak of WWI, Wilson, his backers in Congress and the broader movement of progressive social movements slashed tariffs, pushed through an income tax, passed the Clayton Antitrust Act and created the Federal Reserve system. This was a radical agenda designed to rebalance America’s gilded age political economy. But whatever its ambition, in terms of its overall size, the US government machine in the early 20th century was tiny. As a share of US GDP, in the period 1911-1915 Federal spending made up less than 2 percent of US National Income.

Furthermore, not only was government tiny and ill-equipped for mass mobilization, but Wilson and other leading figures in his administration wanted to keep the US out of the war. They were not friendly to the Entente (UK-France-Russia-Italy) war effort. Wilson had a new vision for American leadership but it centered on the idea of “Peace without Victory” i.e. the humbling of all the European war-fighting parties. This is the story told in my book Deluge. Rather than the US government intervening directly in the political economy of foreign countries, as in the 1940s with Lend Lease and the Marshall Plan, in the first phase of World War I, it was US private capital that collaborated with Entente governments to mobilize the resources of the US national economy.

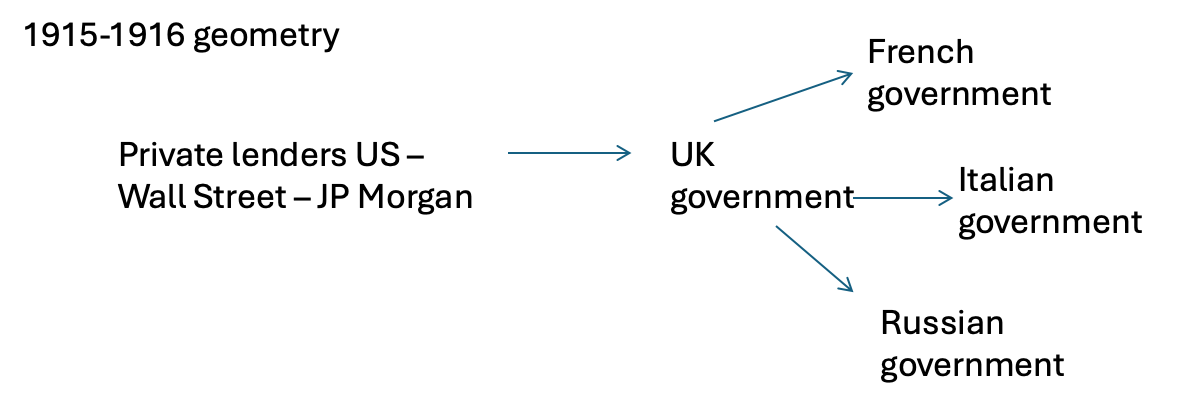

America’s financial system at the time was still highly decentralized. An integrated national system would emerge from the war. The main hub of big money was in New York on Wall Street, which was solidly Republican (the opposition to Wilson) and favored the Entente. The creation of the Federal Reserve Board in 1913 in Washington DC rather than in New York had been a challenge to those interests. Without leadership or instruction from Washington, JP Morgan between 1914 and 1916 set about mobilizing US loans for the Entente with which they could fund large-scale purchases of war supplies in the United States. This involved a fundamental shift in the flow of credit when compared to the prewar period.

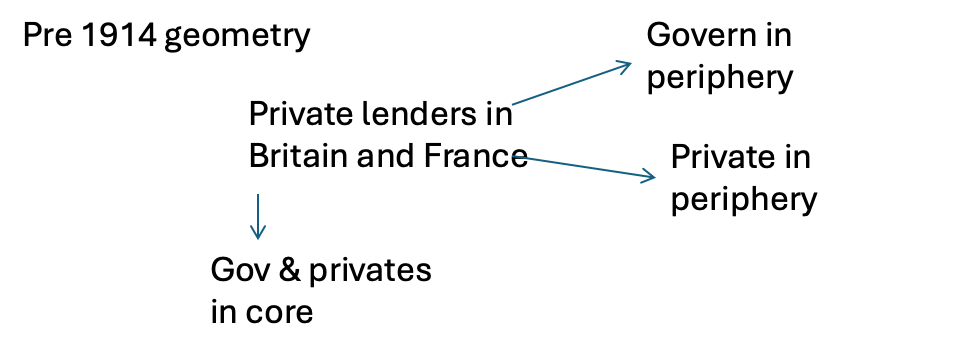

In the prewar period, private lending flowed from the financial core in London and Paris to the periphery, very much including the United States.

With the outbreak of the war, the flow reversed.

JP Morgan coordinated a huge flow of credit from private lenders in the US, formerly the periphery, to the governments of the most powerful coalition of imperialist powers (the Entente) engaged in a war, in which America was officially neutral.

This was both politically and financial precarious. It exposed the US economy to the risks of the war and the fate of one coalition in particular. In the early stages of the war, the purchasing offices employed by JP Morgan funneled more goods to the Entente than the entire US economy had exported before the war. It ran squarely against the intentions of Woodrow Wilson, who in November 1916 was narrowly reelected to a second term. Within days of his victory, Wilson instructed the Fed to put a spanner in the works of the JP Morgan-Entente system. The Fed let it be know that it no longer approved of the private issue of loans to the war-fighting parties.

For the Entente, and notably for the British this was horrifying. British Chancellor (Treasury Secretary) Reginald McKenna on the basis of data supplied to him by John Maynard Keynes remarked: ‘I venture to say with certainty that by next June [ 1917 ] or earlier the President of the American Republic will be in a position, if he so wishes, to dictate his own terms to us.’

What might have been, we will never know. Despite the entreaties of their embassy in Washington DC, Germany’s warlords refused to take seriously Wilson’s intention to impose a peace - an outcome, which at the time would have favored Germany. They did not appreciate how severe a blow Wilson had struck against the Entente war effort with his ban on further loans. Instead, Berlin resolved on a military attack against the Allied supply lines, unleashing unrestricted U-Boat warfare. Germany’s headlong aggression forced the Wilson administration reluctantly into the war.

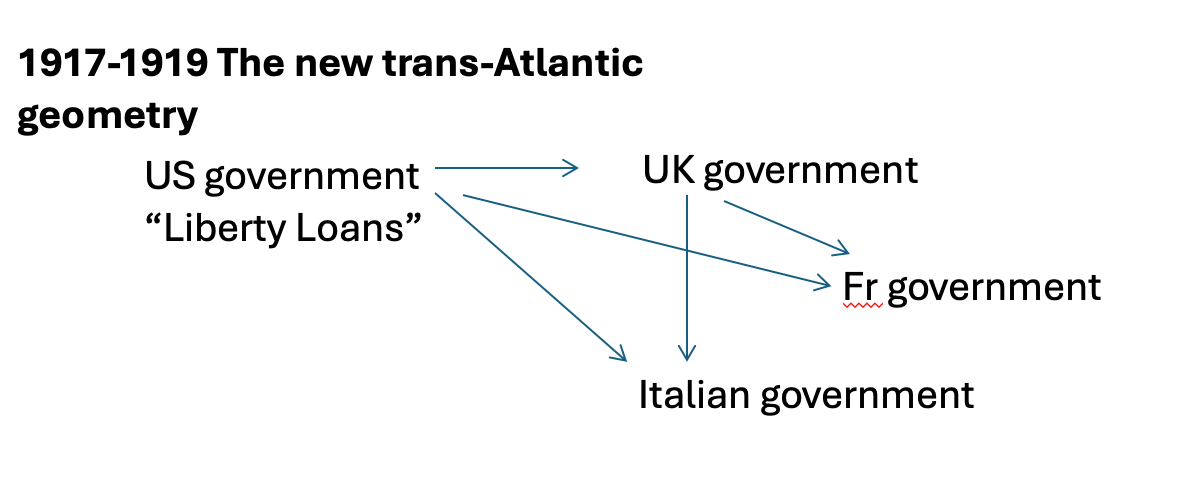

It was war that forced the expansion of the US government apparatus and its fiscal-financial capacity, not the other way around. Working with the Entente, Washington now strung together a new system of war finance that took on a radical new geometry.

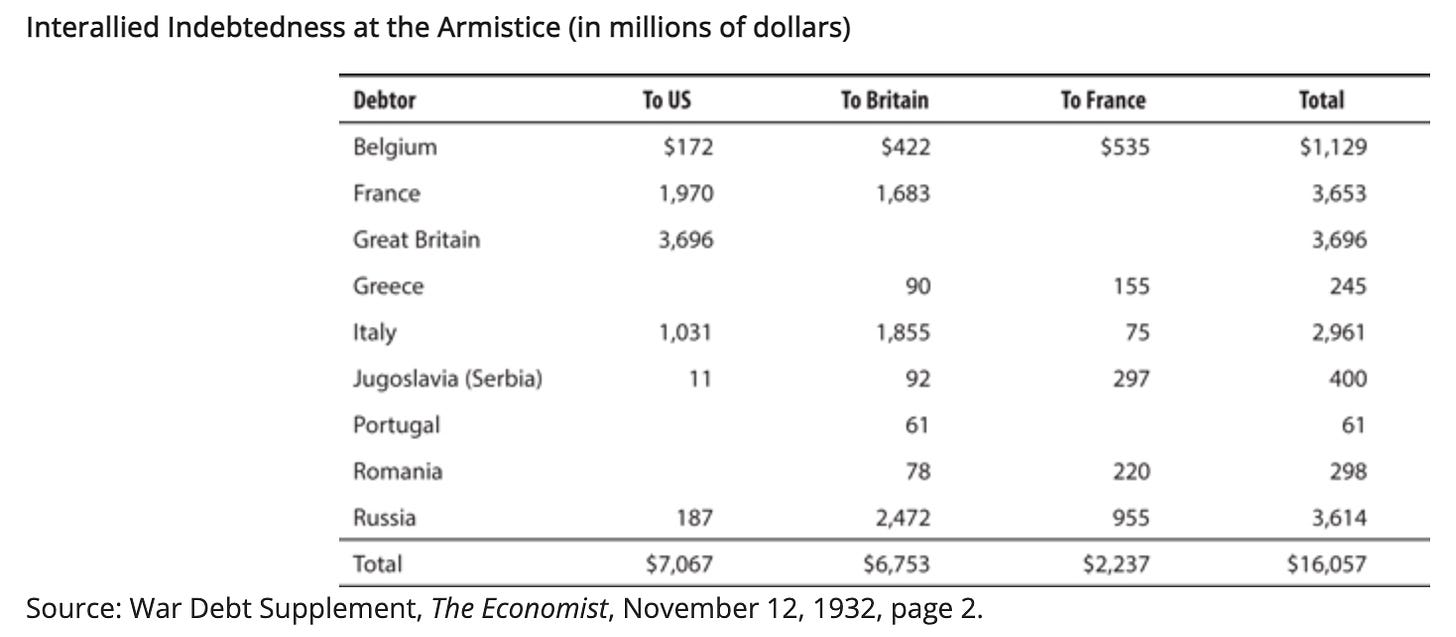

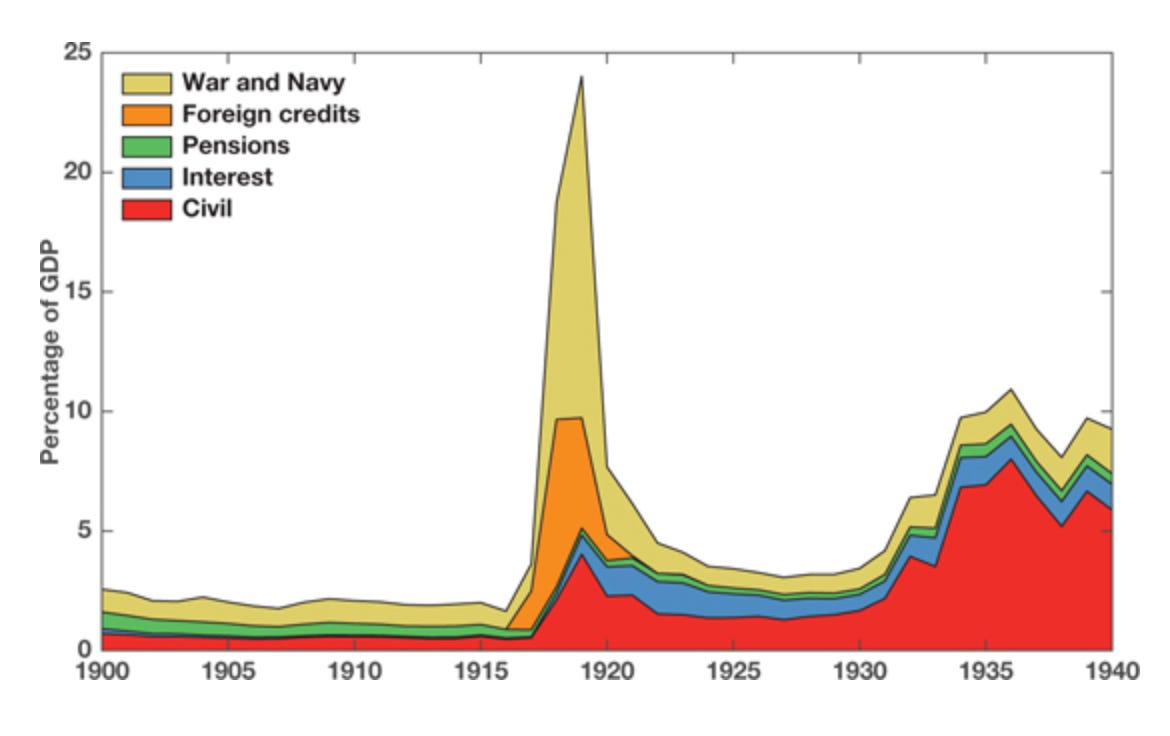

On an even larger scale than under JP Morgan’s management funds flowed from the US (the former periphery) to the former center of power in Europe. Unlike in the first phase of war, money flowed from government to government. Rather than issuing debt on Wall Street, the US government issued so-called Liberty Loans, whose proceeds flowed to the Entente. Democracies were directly financially entangled with democracies, tax-payer on tax-payer, voter on voter. By the end of the war, a giant network of financial obligations connected the European powers to the United States. (Note Russia was knocked out of the war in 1917. The debts shown below were parr of the pre-1917 financial flow orchestrated by London).

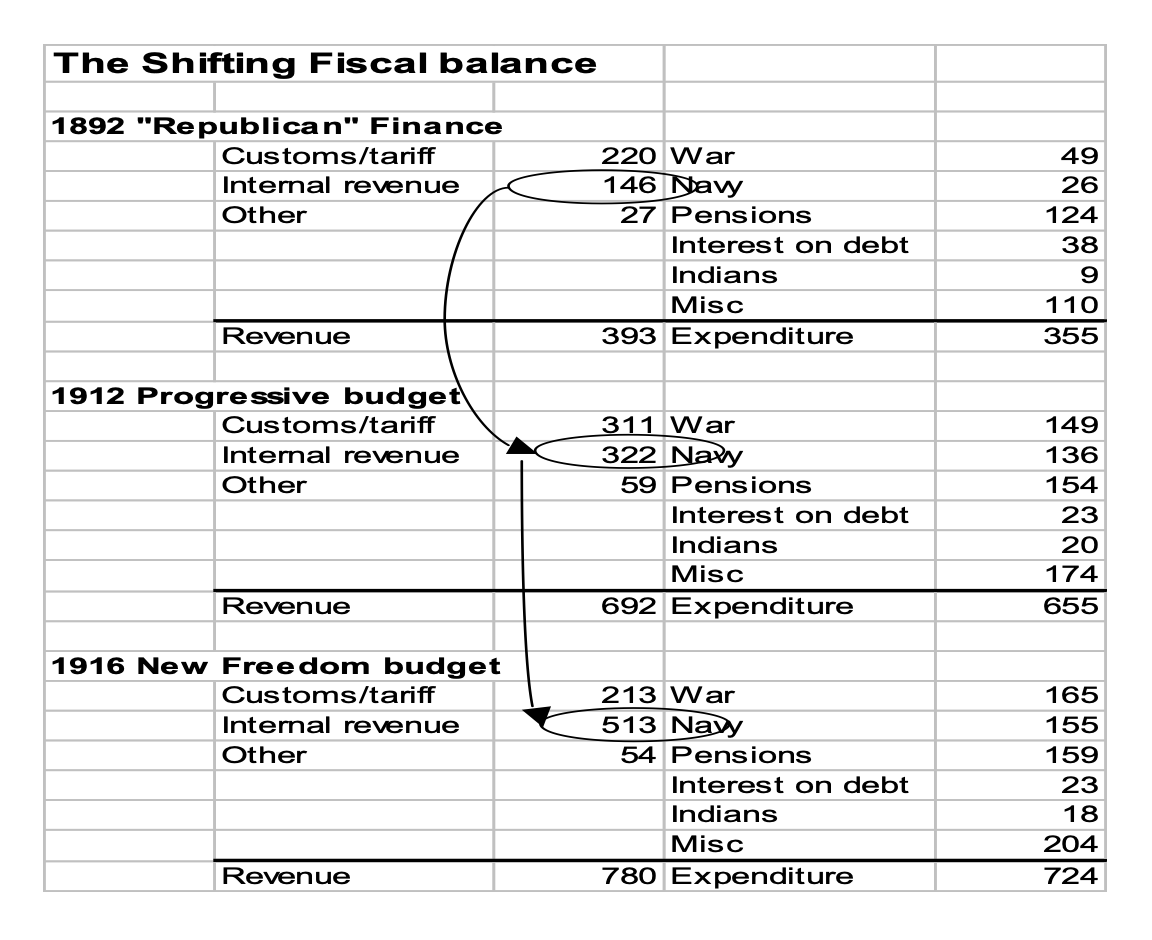

This new system of inter-Allied finance went hand in hand with the dramatic expansion of American fiscal capacity that began during the war. America financed its own war effort in large part out of war debt. But to sustain those it also raised taxes. The upheaval in the US government fiscal system during the war intensified Wilsons transformation of America’s political economy. The progressive budgets of 1912 and 1916 had both seen substantial increases in “internal revenue” i.e. various types of direct taxation (income and profit tax) relative to customs and tariff revenue that had previously been the mainstay of Federal revenue, in the manner favored by McKinley.

Then, with the entry of the US into the war, direct taxation, notably excess profit taxation soared.

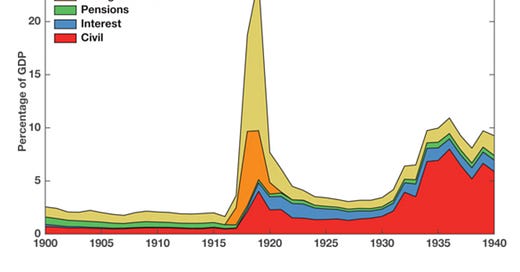

The mobilization that this new fiscal apparatus enabled was dramatic. On top of domestic civil spending, US foreign credits in the form of Liberty Loans reached New Deal proportions in the later stages of World War I. With military spending on top, the Federal government share of GDP rose from 2 percent to almost 25 percent.

Source: Hall 2019 IMF

It is around this radically new system of internal fiscal mobilization and domestic and international finance that the modern question of hegemony was first articulated, both domestically and externally. Now, for the first time, the American federal government had not just the national economic capacity (GDP), but the state apparatus and the financial instruments to make all the major old world imperial powers into its financial clients.

It was a potent combination in carrying the coalition to victory and establishing an American President for the first time as the ultimate arbiter of world affairs. But at home and abroad this hegemony was always fragile and contested. Public-to-public, democracy-to-democracy debts created painful political dilemmas. The trade offs were inescapable. In December 1922, a total of 20 nations owed the US Treasury $11.8 billion. The face value of those foreign loans represented 52 percent of privately held US federal debt and 16 percent of US GDP in 1922. Any significat concession to the wartime “associates” of the USA would rebound directly and to a significant degree on US tax-payers.

And it was not just the foreign loans that were controversial. Wealthier Americans hated the new tax regime. t the insistence of the populist wing of the Democratic Party, the wartime income and profit taxes were highly progressive. The backlash began in the midterms of November 1918, in the final days of the war. For the first time in a US election, the Democrats found themselves accused of socialistic tendencies. This incongruous label was justified by “soak the rich” taxation and by Wilson’s telegram exchanges with Berlin, which earlier in the year had made peace with the Bolsheviks at Brest-Litovsk. The result was a Republican victory that undermined Wilson’s capacity to broker a peace at Versailles in 1919. Having forced his vision of a postwar order down the throats of the British and French, the refusal of the Republican majority in the US Senate to ratify Wilson’s own League of Nations Covenant was the notorious beginning of what later propagandists would dub “isolationism”, the first failure of hegemony.

What is less often noted is the collapse of the political economy of the Wilsonian project. Domestic political resistance made it impossible to broker a generous bargain over wartime inter-allied debts. That in turn triggered exorbitant French and British reparations demands on Germany. The pressure on world finances created by America’s refusal to grant debt relief to Britain and France, was compounded by the domestic push to bring inflation under control, slash wartime spending and reduce top tier tax rates. In 1920-1921 America delivered a savage deflationary shock to the world economy, a memory that still lingered after 1945 and will be the subject of a future hegemony note.

The point to be made here is that WWI opened the door on a radically new era of great power relations. Thanks to the consequences of the war, the United States was more central than any power previously had ever been. This was not the Victorian “hegemony” of the British Empire reimagined. After 1918, the US did not fail to fill a position of global leadership vacated by Britain. The world under modern democratic political conditions had never before had the hub and spokes pattern created by the immense mobilization of World War I. The public in Britain and France were outraged at the prospect of being reduced to dependent clients of the USA. Little wonder that the first US effort to manage these new relations failed catastrophically between 1917 and 1923.

(Note Russia was knocked out of the war in 1917. The debts shown below were parr of the pre-1917 financial flow orchestrated by London).

I think the real lesson for our times is how Russia was "knocked out" of the war and how it's withdrawal led very quickly to the end of the war, a horrific years long slaughter of the youth of Europe.

If the US was "knocked out" of attacking/provoking Russia through Ukraine, knocked out of supporting the genocide of the Palestinians in Israel, humanity would benefit immensely. So, what was that knock out technique of Russia? That deserves much more attention as we stand looking into the abyss of a nuclear WW3. For your purposes, there was also also a fascinating economic experiment bound up with Russia's exit from WW1.

The history of how the US became US imperialism is interesting, but that history is coming to its logical end. It is undeniable that US imperialism is in an irreversible decline and it's taking its junior partners in Europe down with it, quite quickly. If it goes on like this much longer it will take every living creature on earth down with it.

An interesting analysis of how the US kind of "backed into" its central position where international debts are concerned. A rather less sympathetic narrative can be found in Michael Hudson's "Super Imperialism: The Economic Strategy of American Empire, Third Edition" (the first edition of which came out in 1972) or the early chapters of his "The Destiny of Civilization: Finance Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism or Socialism" published in 2022.