Chartbook 272 The case for a big vaccine push (despite the political economy). It's time for a new golden age in global health.

This month’s column for the FT made the case for a big push on vaccine investment as an essential tool to meet the challenges of an era of polycrisis.

Vaccinations have been one of the unalloyed benefits of modernity. But after COVID they take on a new aspect

a. with the sharpened awareness of the risk of truly global and devastating anthropocenic shocks.

and

b. with the possibility of developing new vaccines in something close to real time, not after but as a pandemic unfolds.

Vaccines are one of the obvious responses to the complexity of our current situation and should be understood as core elements of both economic policy and national security policy. So we should go big and spend far more than we do.

All this might seem obvious. But, as is often the case, spelling out exactly why, turns out to be surprisingly worthwhile.

The currency of the idea of polycrisis marks a “knowledge crisis” (h/t Michael Geyer). We invoke the term because can see that there are a lot of forces at work and they interact, but the combination of shocks exceeds our ability to provide a coherent explanation or interpretation. We lack adequate concepts with which to grasp our situation. Polycrisis marks that feeling of perplexity.

Understood in this way, polycrisis is a reflexive, second-order concept. It describes both a state of the world and our reaction to it. Acknowledging that we face a polycisis is, therefore, a challenge to simplistic conceptions of rationality. How do we think about doing good policy under conditions of polycrisis? How do we weigh means and ends?

The most ambitious response is to look for what some people have dubbed polysolutions. So-called “Swiss army-knife strategies” are the elaborated form of that. Sensibly they aim to deploy what limited resources are at our disposal to fix several interconnected problems at the same time. The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act is a Swiss army knife strategy par excellence. With whatever funds could be squeezed out of Congress, the IRA aims to address the climate crisis, the competitive threat from China, the crisis of the American working-class and even claims to fight inflation (… nudge, nudge, wink, wink), all at the same time.

This kind of optimizing approach is ambitious. It presumes that we do, in fact, have a pretty good idea of the major challenges and how they hang together. Under the circumstances, that is a strong assumption to make.

A more modest approach seeks out fixes with quite limited scope which yield exceptionally high rates of return and have the potential to limit and contain shocks. Of course, each such fix comes at a price. Ideally, we would like to optimize the allocation of resources by weighing one fix against another. But that would presume having an overarching model, which is what we lack. So it make sense to pick high value fixes of modest cost and do those, even if we have no certainty that our selections meets the ultimate standard of optimality. Call this the low-hanging fruit scenario. There may be better fruit higher up the tree, but the low-hanging ones are tasty enough and easy to reach.

Finally, when the polycrisis hits us hard, as during the pandemic, the overlay of crises can become so overwhelming that we simply MUST have a fix for the most immediate driver of the disaster. We need this fix, whether or not the resources are used efficiently or other problems also call out for attention. We need a magic bullet. Our mantra becomes: “Just make it stop!” (Whatever “it” is). Stopping the most immediate cause of pain or confusion is a precondition for being able to do anything else.

Vaccinations, depending on the circumstances and the disease, have aspects of all three of these logics.

The vaccinations for COVID freed us from the impasse of the lockdown and social distancing - they were the magic bullet that “made it stop”.

By contrast vaccinations against Malaria, are a key part of a comprehensive long-term strategy of unlocking human potential in developing countries - they are a vital gadget in a Swiss army knife package.

A vaccination against HPV significantly reducing the risk of cancer in women, falls under the heading of low-hanging fruit. It addresses a specific risk at modest cost.

Developing vaccines isn’t free. But a billion dollars or two is enough, according to those who know, to push at least one viable candidate to phase 2 trials for even the toughest diseases. By the standards of big business or big government or big wealth, $ 1-2 billion is not a lot of money for a potential solution to a major global problem, which in the case of COVID or Malaria affects billions of people and claims millions of lives. The question is why we arent splashing this spending right left and center.

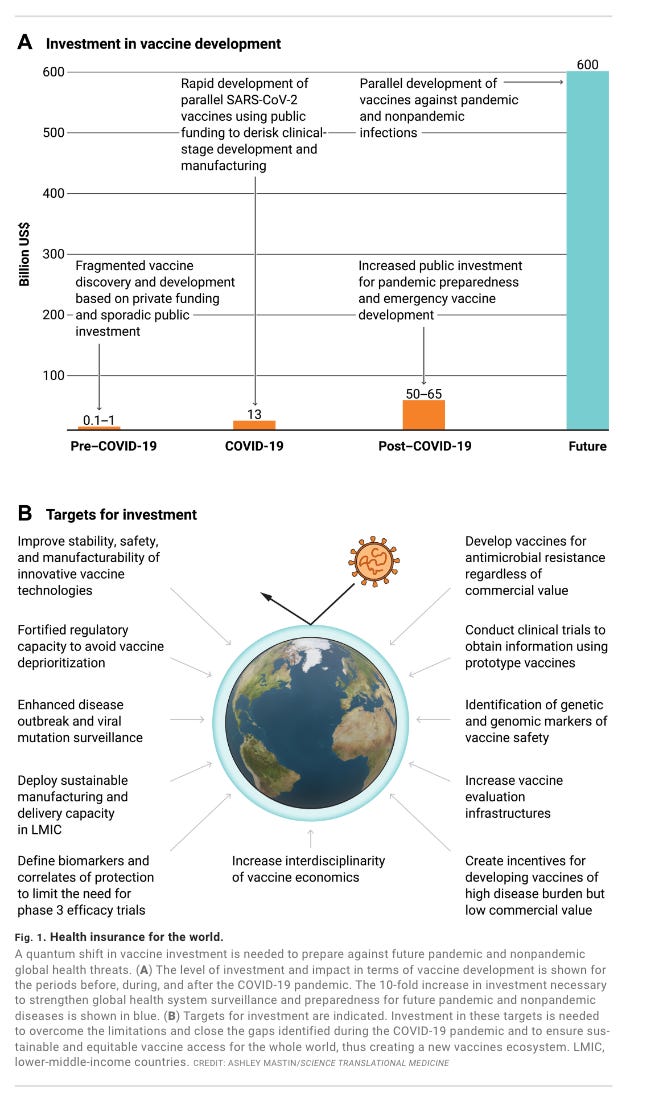

A fairly comprehensive library of early-stage vaccines for the known pathogens that we are worrying about, has been costed by experts at c. $50 billion. That is the kind of figure discussed by Kate Kelland in Disease X, her book about the work of CEPI - the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

In Science in 2022, a team of authors make the case for a even more gigantic vaccine investment push, which they cost at c. $600 billion.

As the COVID vaccine-race demonstrated we can not only afford vaccine development - in fact, it pays for itself many times over - we can do it in real time. In the face of a pandemic shock, vaccines can be developed and deployed not at the pace of monetary policy, but far faster than infrastructure construction. Not for nothing the IMF declared vaccine policy is economic policy.

The COVID vaccines helped us restore normality. They were produced unprecedentedly quickly. But the delay was nevertheless agonizing. Global coordination through the so-called COVAX facility worked badly.

Source: “COVAX and the rise of the ‘super public private partnership’for global health”, Storeng et al Global Public Health 2023

Fears of shortages and delays led to hoarding and vaccine nationalism. Predictably, the richest countries, led by the United States, hoarded most. Low-cost production for poor countries depended heavily on suppliers in one country, India. By the time vaccines were made available through COVAX for poorer countries they no longer seemed relevant, discrediting the entire exercise.

We were lucky that later variants of COVID were less lethal than they were. We may not be so lucky next time. The chance of a new pandemic of at least COVID-scale in any one year is rated at c. 2 percent. And that probability is rising. It is not, therefore, a question of “if” but of “when” the next pandemic arrives.

To meet this threat, CEPI has launched what is called the “100 Days Mission”. The genesis of this program is described in the journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases as follows:

On March 7 and 8, 2022, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the UK government cohosted the Global Pandemic Preparedness Summit in London, UK (1). More than 300 participants from governments, academia, industry, philanthropy, and civil society gathered to explore a proposed response to the next “Disease X” by making safe, effective vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics within 100 days of identification—a goal that the UK government designated the 100 Days Mission (2). This goal was originally articulated by CEPI, an innovative global partnership between public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organizations launched in Davos, Switzerland, in 2017 to develop vaccines to stop future epidemics. The 100 Days Mission concept is part of CEPI’s 2022–2026 pandemic plan and has been endorsed by the Group of Seven forum, the Group of Twenty forum, and other governments around the world. Several vaccine developers are exploring strategies to achieve this aim

So, yes, we are talking about “the usual suspects”. CEPI is one the most significant initiatives to come out of Davos in the last ten years. And no, it is not a coincidence that the foreword for Kelland’s book is attributed to Tony Blair, or that the statement on competing interests that follows the Science paper calling for a $600 bn vaccine investment, states the following:

Competing interests: S.P., M.P., F.B.S., and R.R. are full-time employees of the GSK group of companies. D.T. consults for GSK, Merck, and Pfizer. S.B. consults for GSK, CEPI, the FDA Best Project, and the European VAC4EU project. D.E.B. reports consultancy fees or research funding from Merck, Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi, and Moderna.

There is no innocence here. Vaccines development has always been interwoven with the political economy of public health and pharmaceutical development. Since the early 2000s, shaped at first by the AIDS/HIV crisis this political economy has been defined by

The merging of public health strategy with economic development.

Public-private partnership in loosely structured and legitimated coalitions.

Global reach beyond individual nation states, though US public health spending plays an outsized role.

Large role for philanthropy whether though oligarchic mega-donors (Gates foundation) or corporate philanthropy (Wellcome Trust).

Tellingly, in 2020, in its first weeks, before the true reality hit, the COVID pandemic was framed by many political actors, notably in Europe, as a developing country problem, true to the global health framing that has been predominant since the early 2000s. It is an open question whether the impact of the pandemic will fundamentally shift that understanding, causing rich countries to deeply understand their own vulnerability and to pool their resources and commitment with global endeavors.

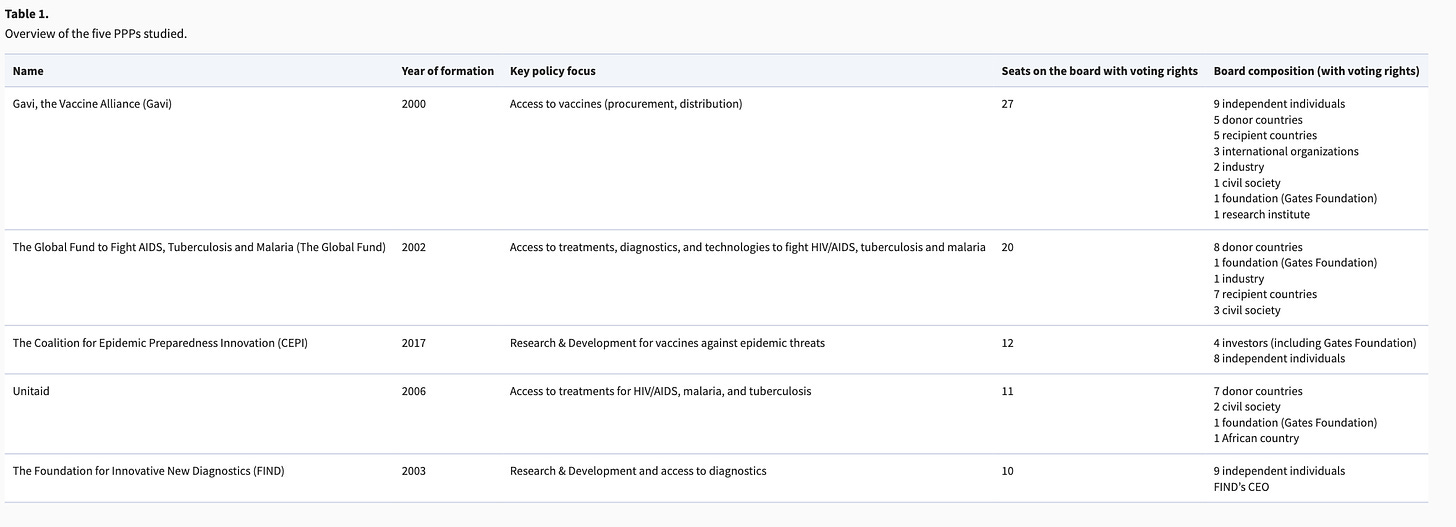

In the elaborate structures pulled together to address the COVID shock, representation was distributed very much according to the standard PPP-global health framing of recent decades. The Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) aimed “to bring covid-19 vaccines, tests and treatments to everyone, everywhere”. Seats on its board were divided between Gavi, the Global Fund, CEPI Unitaid and FIND as follows:

Source: “The rising authority and agency of public–private partnerships in global health governance” Antoine de Bengy Puyvallée Policy and Society (2024).

This structure was broadly speaking a disappointing failure. You might ask, therefore, why in the FT piece all I say about all this is that we cannot rely on the private sector to fund vaccine development and must instead call for greater public spending? This may be true, but will this not simply feed the public-private partnerships and perpetuate the lop-sided structures of the present? Perhaps it will. Certainly, Pfizer and Moderna did well out of their COVID vaccines and nowhere near enough of those shots were supplied to lower-income countries.

But facing the polycrisis, should profiteering and distributional issues really be our main focus? I take this to be another version of the question implied above by the distinction between swiss army knife (optimization) strategies, opportunistic low-hanging fruit strategies and silver bullet strategies of desperation (Just make it stop).

If the public-private global health complex was threatening to swallow truly huge quantities of money and divert them in inefficient ways, that should clearly be our priority. But that is not our situation.

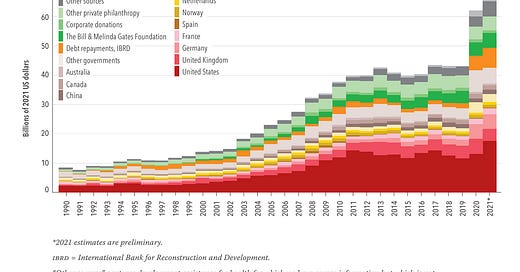

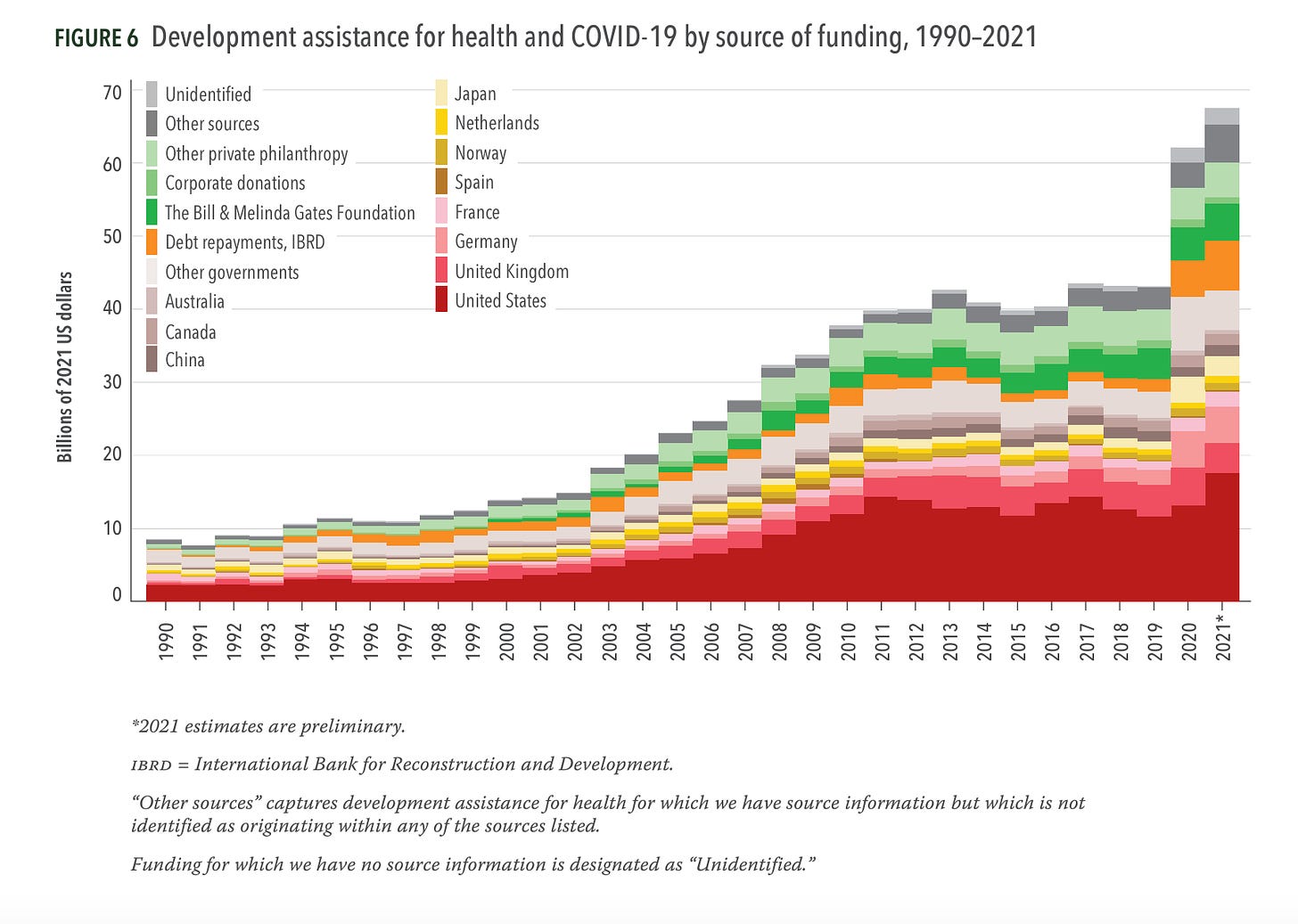

Source: Funding Global Health 2021

After growing dramatically between 2000 and the 2010s, the public-private global health complex, shot through with all its conflicts of interest and maldistributions of influence and power, plateaued in the 2010s, at a remarkably steady funding level of $40 billion. It remained at that level with tiny variations for the entire decade from 2010 until 2020, when COVID hit. Whatever those private interests were doing, they were not successful in shaking the money tree for an expanding flow of funding. As a share of global gdp, the flow into global health was shrinking.

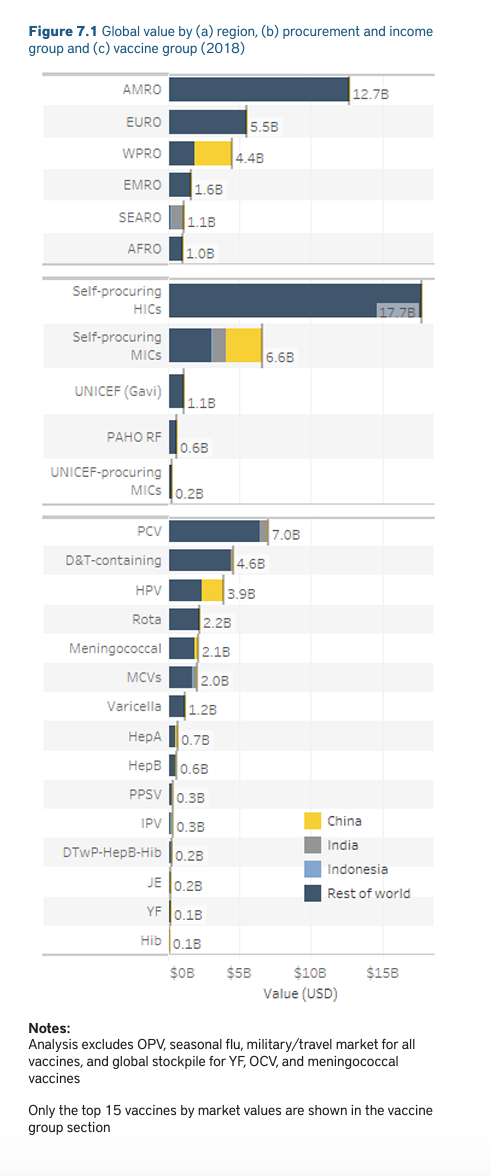

If we focus specifically on vaccines, prior to the pandemic they were not a booming market in which oligopolists expected to make billions in profits. The WHO report on the global vaccine market for 2019 described a relatively placid global business, distributing 3.5 billion shots per annum, generating a market size of $26 billion, not including seasonal influenza, travel or military demand.

Source: WHO

The fact that Pfizer and Moderna made billions from their COVID shots, results from the scale of the shock, the fact that it hit rich countries as badly as poor markets and that they were able to develop a vaccine in time to actually meet the pandemic. This combination is not the norm. It is unprecedented. Their profits are, one might be tempted to say, a good problem to have.

Clearly, public health institutes must think carefully about how they design contracts in future for the development and procurement of vaccines. And the private-sector biases of influential funders like the Gates Foundation should be checked. But, with the recent history of global health in mind, the first priority is simple: Ramp up spending. Break out of the entirely inadequate plateau of global health spending that characterized the pre-pandemic era. The priority must be to step up spending, the pace of development and the scale of production capacities to new levels and to do so in as many sites around the world as possible, as quickly as possible. We need a new golden age in global health, even if that means inviting the usual suspects to the party.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

"The vaccinations for COVID freed us from the impasse of the lockdown and social distancing - they were the magic bullet that “made it stop”."

So, the government forced small businesses, churches, restaurants , beaches, outdoor basketball courts to close, but liquor stores and Walmart could remain open (and of course Antifa demonstrations were fine); masks were required; social distancing required, which assumed the virus was spread by "droplets" - and those vaccinations "made it stop"?!

Reading "The vaccinations for COVID freed us from the impasse of the lockdown and social distancing - they were the magic bullet that “made it stop”. is LOL funny