The war in Ukraine has become a battle of material and in a jarring inversion of the familiar balance the “Western side” does not have the upper hand.

Even if funds are available, both the Europeans and American producers lack the capacity to manufacture the munitions Ukraine desperately needs.

According to one recent estimate in the FT, there is a stark disparity between the ammunition production of Russia and the West.

Russia’s annual artillery munition production has risen from 800,000 prewar to an estimated 2.5mn, or 4mn including refurbished shells. EU and US production capacity stands at about 700,000 and 400,000 respectively, although the EU aims to hit 1.4mn by the end of this year and the US 1.2mn by 2024.

According to estimates by experts Michael Kofman and Ryan Evans, Russia’s battlefield firepower advantage may amount to 5:1.

The inadequacy of Europe and American supply chains is all too obvious. But we must also ask how Russia is able to sustain its much higher levels of output.

A new report by Rhodus Intelligence, the research outfit set up by Kamil Galeev, addresses this question for the production of missiles.

Missiles are a core component of modern Whereas artillery ammunition is counted by the millions of rounds, the number of missiles fired at Ukraine is counted in the thousands. According to Ukrainian sources, in the first two years of the war Russia used more than 8,000 missiles and 4,630 drones. The missiles are sophisticated ordinance with powerful rocket engines and guidance systems.

Often their production is treated as principally dependent on electronic components. A tear down of both Russian and North Korean sourced missiles confirms that a large number of these electronic components are still finding their way to Russia from the West.

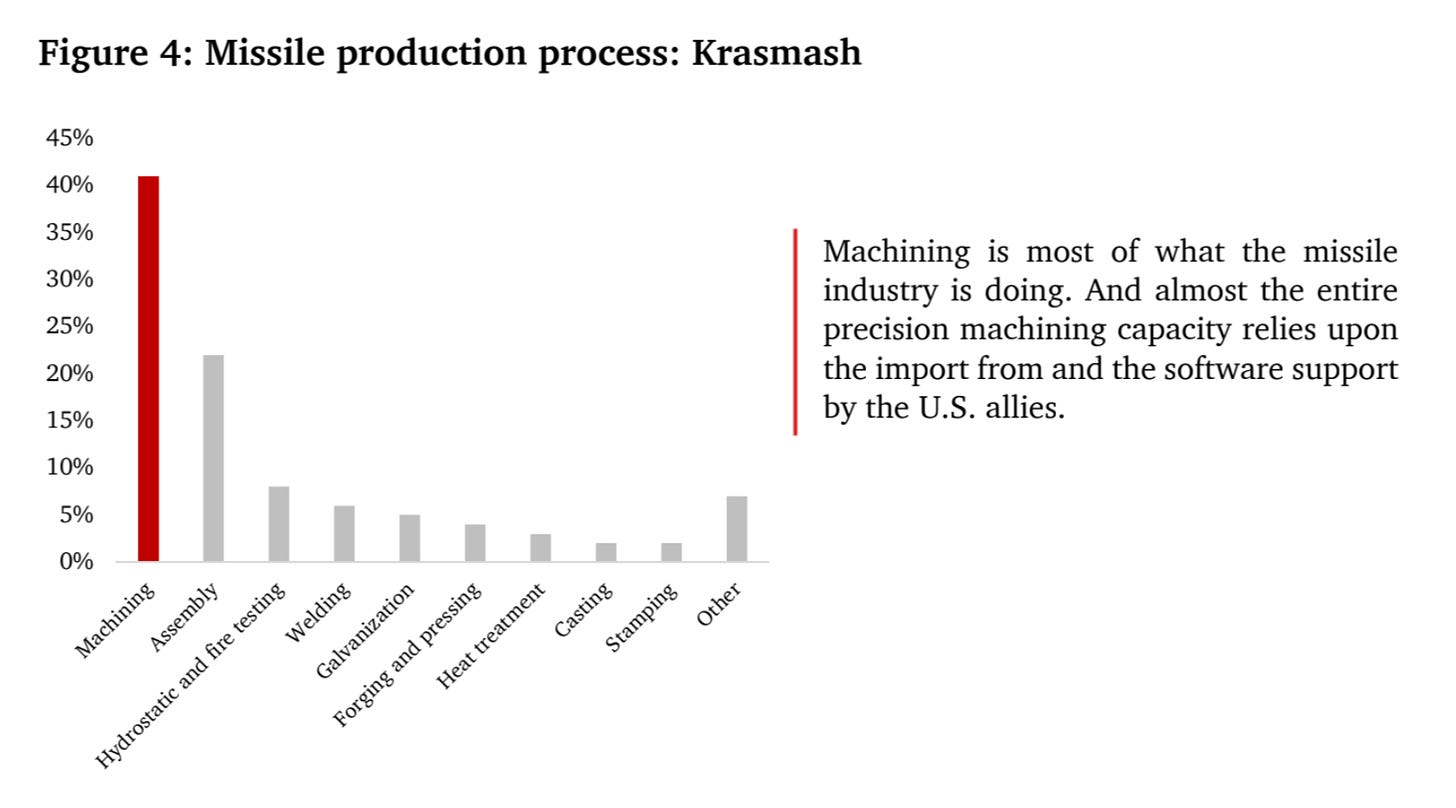

But, as the Rhodus team point out, the most tricky part of modern missile production is not so much the electronics as the metalworking and, in particular, the machining.

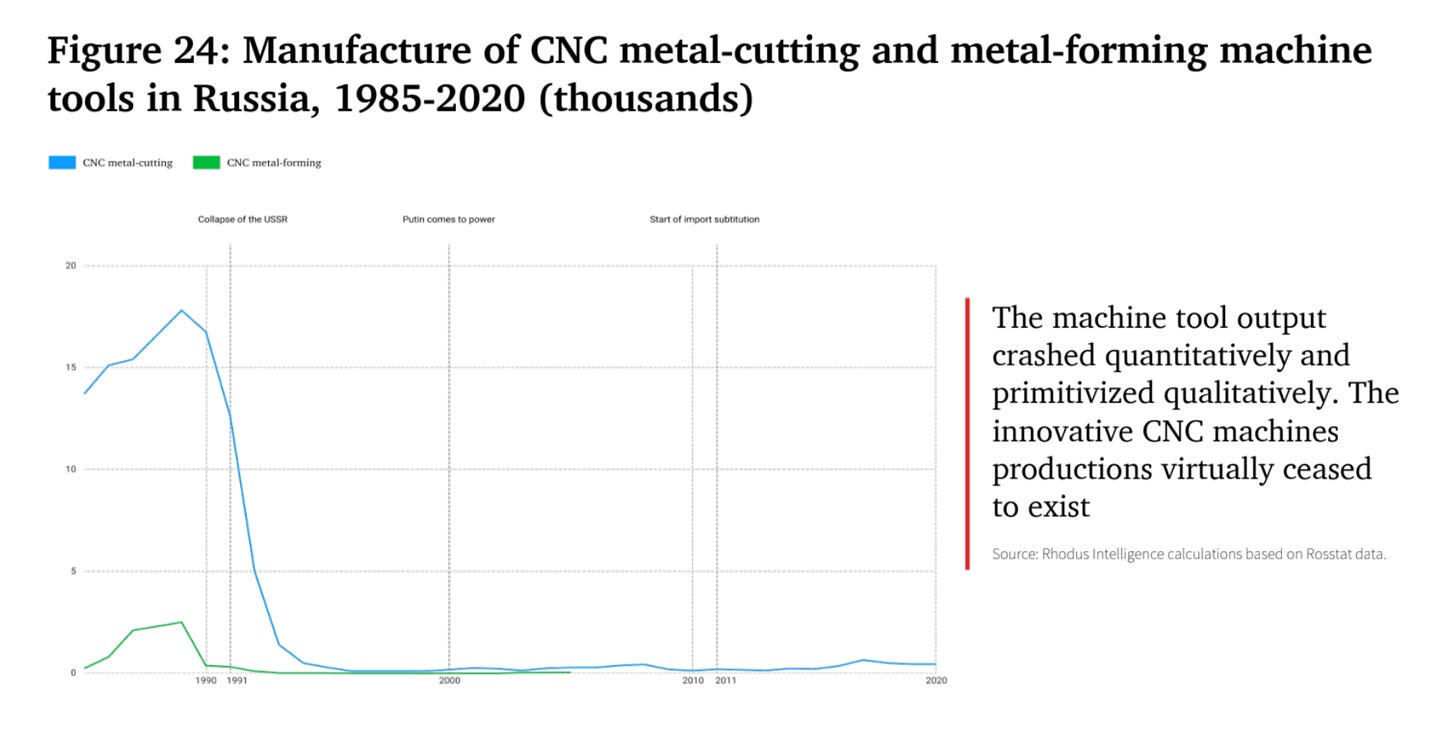

Beginning in the 1930s the Soviet Union built a gigantic machine tool industry and the workforce to go with it. Soviet designs were never noted for their sophistication. But by the late 1980s the Soviet Union was the largest producer of computer-controlled CNC machines, worldwide. In the 1990s the collapse of the Soviet Union destroyed this industry and dispersed its workforce.

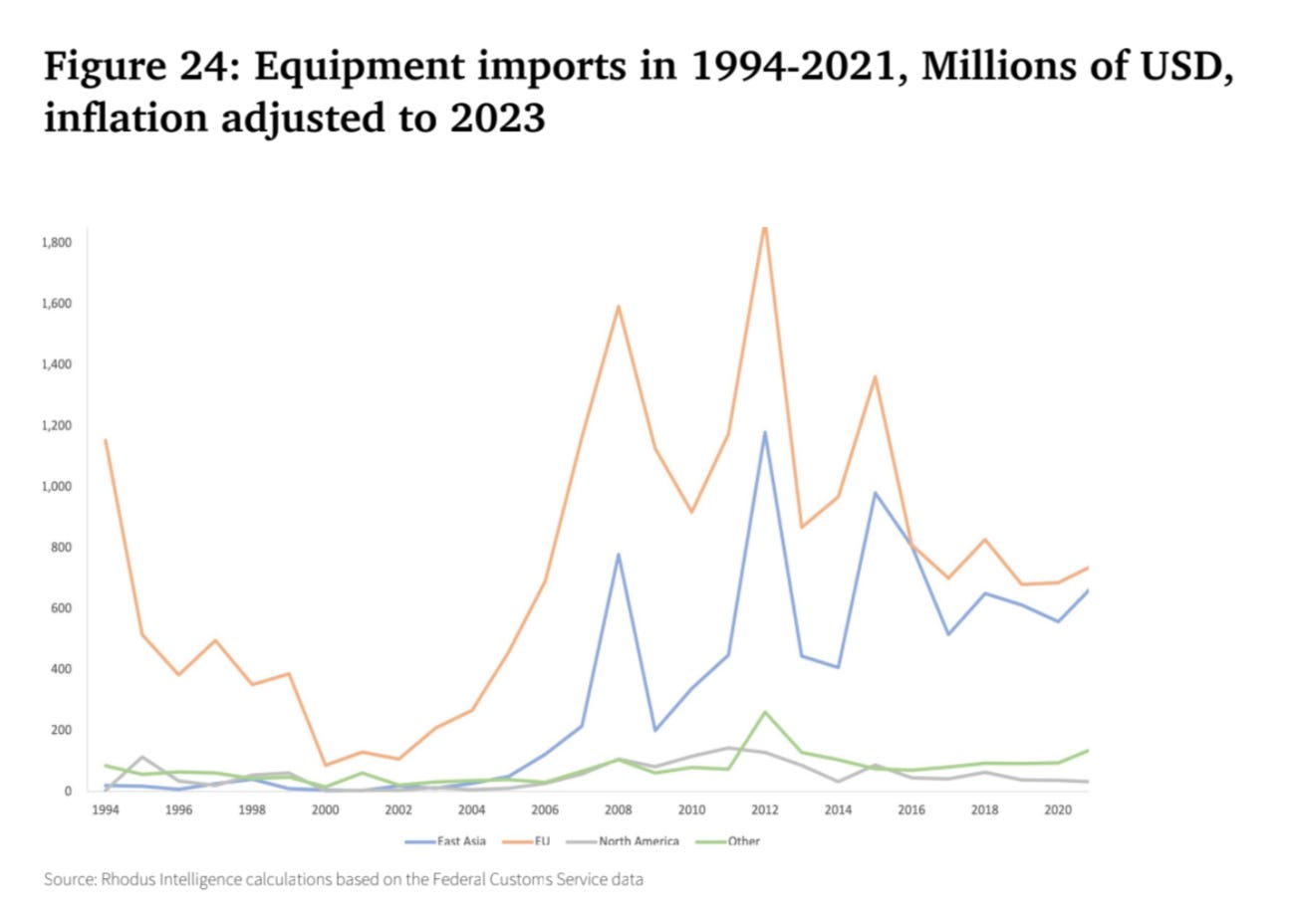

As the Rhodus group show, from the early 2000s Putin’s regime set about replacing domestic production with imports.

The trade statistics give a general idea of this import drive. But what makes the Rhodus report unique is that it goes beyond aggregate data to track the equipment installed in 28 ballistic, cruise, anti-ship and air defense missiles producers. To do so they deploy imaginative open source intelligence techniques.

For instance, they track the machines shown inadvertently in the background of TV coverage, such as this image from the Titan-Barrikady works in Volgograd - a legendary battlefield during the siege of Stalingrad in 1942.

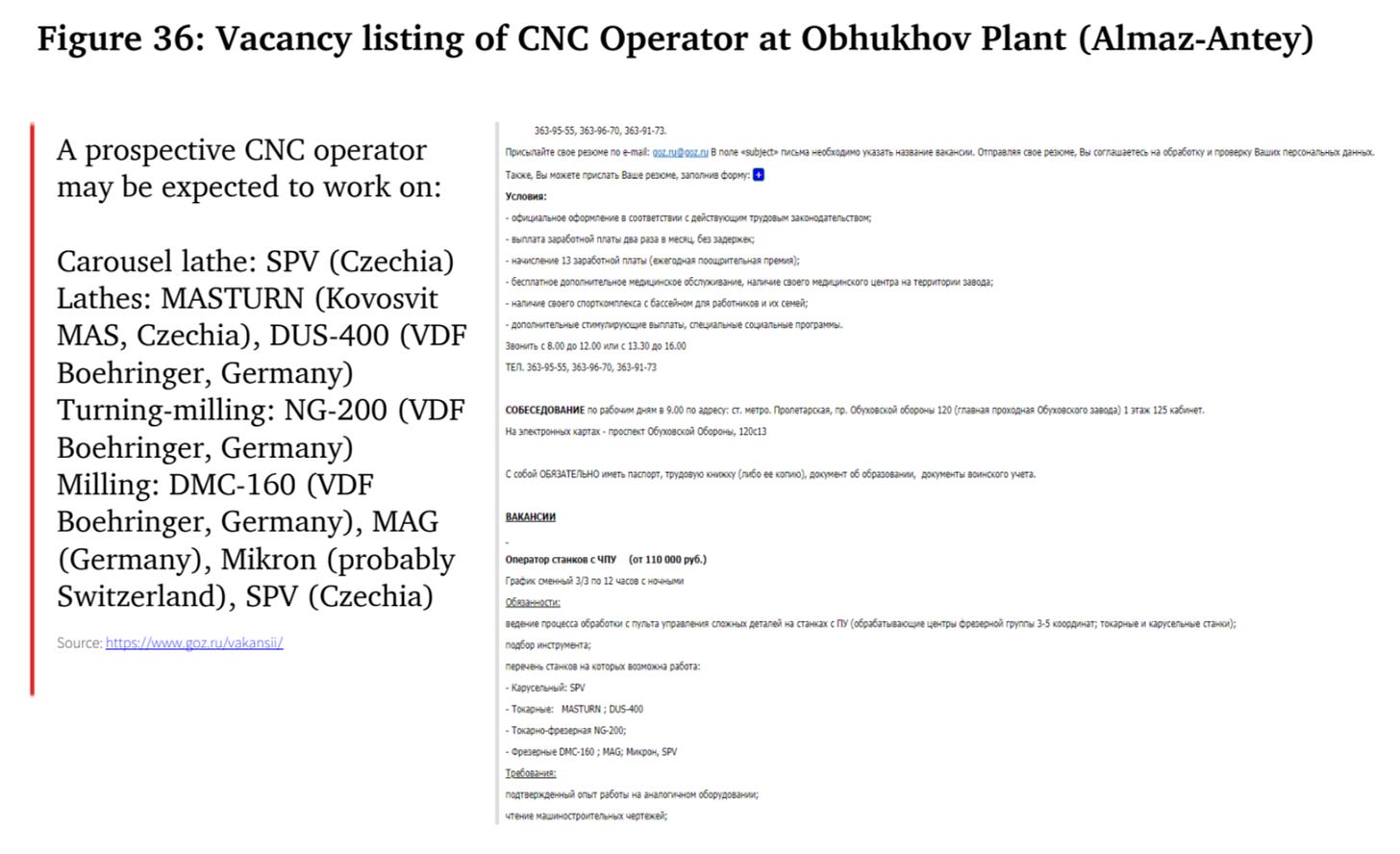

In addition, Rhodus have trawled through job adverts to find the types of tools, which Russian CNC operators are expected to be able to use.

To savor the rich detail in this extraordinary report, I highly recommend downloading it from the Rhodus website. For anyone interested in the realities of modern production, it is a feast of intelligence analysis. We would be well-served if we understood more production processes at this level of granularity.

As far as Russia is concerned, the conclusions are sobering.

To escape the constraints imposed by its depleted and unskilled workforce, from the 2000s Russia opted to import the most advanced, computer-controlled machines. These could not be purchased from China. Instead, Russia relied heavily on leading Western producers notably in Europe and in particular Siemens of Germany, which specializes in fully integrated manufacturing systems.

This creates a heavy dependence on the West. But machine tools are capital equipment. The machine tool stock at Russia’s disposal is large and well-chosen. In the core area of machining, its tools are particularly modern. Pressing and forging equipment is on the whole older, in many cases upgraded cold war technology. But these are areas where technological advance has been least rapid. The most sophisticated machinery at Russia’s disposal is deployed in the areas of precision casting and foundry work.

Meanwhile, the flow of new machines continues. Police authorities in Europe are now in the business of hunting down rogue German executives selling high-precision tools to Russia. Deliveries of highly sophisticated Swedish and German machinery continue via intermediaries in Turkey. And, most importantly, Russia is surging its import of CNC machinery from China and Taiwan. All told, Russia’s imports of CNC machine tools by the summer of 2023 were more than twice their prewar level. Even allowing for price increases, this is a substantial increase. If sanctions are to have any chance of working, this number needs to fall below pre-war levels.

Source: FT

In China Russia finds plenty of willing collaborators.

A Financial Times analysis of export records shows some major winners from the Russian surge have strong links with China’s People’s Liberation Army. Wuhan Huazhong Numerical Control, for example, has increased exports to Russia. In 2017, it was the main contractor in a “Brain Switch Project” — a scheme to replace foreign CNC systems with domestic ones in the defence industry — and has worked with Chinese jet fighter maker Shenyang Aircraft Corporation. HuazhongCNC was itself the subject of US sanctions between 2008 and 2010 under an act banning the transfer of weapons technology or equipment to Syria, Iran and North Korea. The company did not respond to a request for comment.

As the Rhodus report rightly insists, CNC-machine does not equal CNC-machine. The Chinese machines are lower quality than their European counterparts. Furthermore, it will take time to integrate them into existing production processes. But where there is a will, there is a way. And the remarkable findings of the Rhodus report certainly suggests that it would be ill-advised to expect any rapid end to Russia’s military production surge.

**

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

You know, if the US is worried about running out of bombs, maybe murdering fewer Palestinians could be an option?

Empirical evidence that sanctions don't work is simply overwhelming. As Iranian jokes these days goes, first the US sanctioned Iran to stop them producing missiles, now they sanction them to stop selling those missiles to Russia.