Were tens of thousands of Jews, Soviets and Polish POW worked to death on one of Britain’s channel islands during World War II? Did the Holocaust extend to British territory?

John Weigold.. is a figure shrouded in mystery—a self-proclaimed recluse at the center of what has been a coordinated, and often unruly, effort to rewrite the history of the place he calls home. When he first visited the English Channel island of Alderney as a child, on vacation with his parents from Essex, he sensed what he remembered as a “dark energy.”

Source: Guardian

At the age of sixteen, he did his O-level history project on the abandoned World War II fortifications that dot the island. One day at dusk, he was using a metal detector on an undeveloped patch of grassland called Longis Common (pronounced “lawn-jee”) and felt a sudden chill. The atmosphere had turned somber. “I didn’t know at the time,” he recalled, “but I was actually metal-detecting on a mass grave.”. … The existence of a mass grave on Longis Common was hardly established history—not in the Seventies, and definitely not in 2010, when Weigold began to reexamine things as an adult.

Source: Guardian

Though Alderney was occupied by the Nazis, it hasn’t generally been regarded as part of the Holocaust, or even as a particularly significant part of World War II. … According to Weigold, this attitude is the result of a massive cover-up executed by the British government in the postwar period. …. In the alternate history he constructed, tens of thousands of Holocaust victims were worked to death, and many may have been cremated and buried on Longis Common—a finding that, when he first publicly released it in 2017, was denounced as a conspiracy theory. And it might have been left at that, another crackpot proposition in a supposedly “post-truth” moment, if the existence of a mass grave on Longis hadn’t proved convenient for a consortium aiming to halt the construction of an electrical interconnector in their relative backyards.

Holocaust denial has been outlawed in at least eighteen countries. It is widely considered not only anti-Semitic but dangerous—a historical revisionism that refuses to acknowledge either the humanity of slaughtered Jews or the culpability of German perpetrators and Eastern European collaborators. Less condemnation has been reserved for its inverse: for the theories that don’t minimize or dismiss, but instead aggrandize what Weigold has called the “orgy of beatings, torture, starvation, recreational killing, crucifixion, and systematic mass murder” carried out by the Third Reich. Even today, there are those who claim that as-yet undocumented Nazi atrocities are waiting to be uncovered—amateur historians circulating obscure documents, devising unsubstantiated hypotheses, and weaponizing the term “Holocaust denier” against all who disagree. And because that label is so damning, because the Holocaust occupies such a singular role in the public imagination, it’s not difficult for other, more cynical people to use these unproven accounts to serve private ends.

Rebecca Panvoka’s extraordinary piece in Harpers magazine about the creation of a Holocaust history on an English Channel Islands, is a must read. It tells an intricate tale of NIMBYISM in all its variants, the politics and business of holocaust commemoration and the skullduggery of island politics. It is brilliantly done and contrasts starkly with the facile pastiche that passes for journalism on the same topic at America’s “paper of record”.

**

Beyond the extraordinary machinations that Panovka exposes, what fascinates me about this story is the delirious arithmetic that several of her protagonists engage in. Weigold is convinced that there are 5-7 million unaccounted victims of the Nazi forced labour program, many of whom may be buried in a giant mass grave on Alderney. A tiny island can thus be imagined as a Pharaonic monument … or not!

You might say that this is the curse of amateur expertise, fascinated investigators determined to put two and two together. It is the logic of QAnon calling on its followers to “do their own research”.

But I dont want to play the professional v. amateur game. It is far more interesting to think about the structural determinants of these wild acts of quantification, which are common not only in “amateur” thinking, but in “serious” high-brow commentary as well.

The basic condition for this kind of intellectual gesture, is not the lack of professional training or discipline, but the difficulty of grasping the gigantism and networked complexity of modernity. On the one hand this requires us to stretch our imaginations to grasp the immense scale of reality and at the same time challenges our willingness to draw crucial distinctions and to do the basic work of counting and weighing quantities.

There is a deep tension. One wants to do justice to the immensity of a crime or an act of violence. But the complexity and the inevitable imprecision and obscurity in a giant system make it hard to know where to draw the line. There is a fear of underestimating and undercounting. Given the monstrous nature of reality, any act of delimitation or demarcation can seem frivolous. Indeed, as Panovka points out, it can easily lay one open to charges of “denial”. If one seeks to precisely define a part one fears losing the whole. It can seem safer simply to gesture vaguely towards one big “blob” of modern massacre.

A striking instance of this kind of blurry thinking about the horrors of “big bad modernity” is the Auschwitz-Hiroshima paring that has haunted critical theory since the 1940s. The loose association between two radically different projects of mass killing says more about critical theory’s limited grasp of even the most basic contours of modern technology than it does about the Holocaust, the Manhattan project or “industrialism”.

**

In the case of Alderney no one claims that any particularly complex industrial facilities were being constructed. There is some talk about V1 launch sites and improvised gas chambers in tunnels. But the basic challenge is to locate the tiny island and its four camps in the ramified structure of the Nazi system of foreign labour, forced labour and extermination. This involves three basic intellectual operations: a. drawing a series of important distinctions, b. counting and c. being willing to submit to the basic logic of a spreadsheet and an organigram.

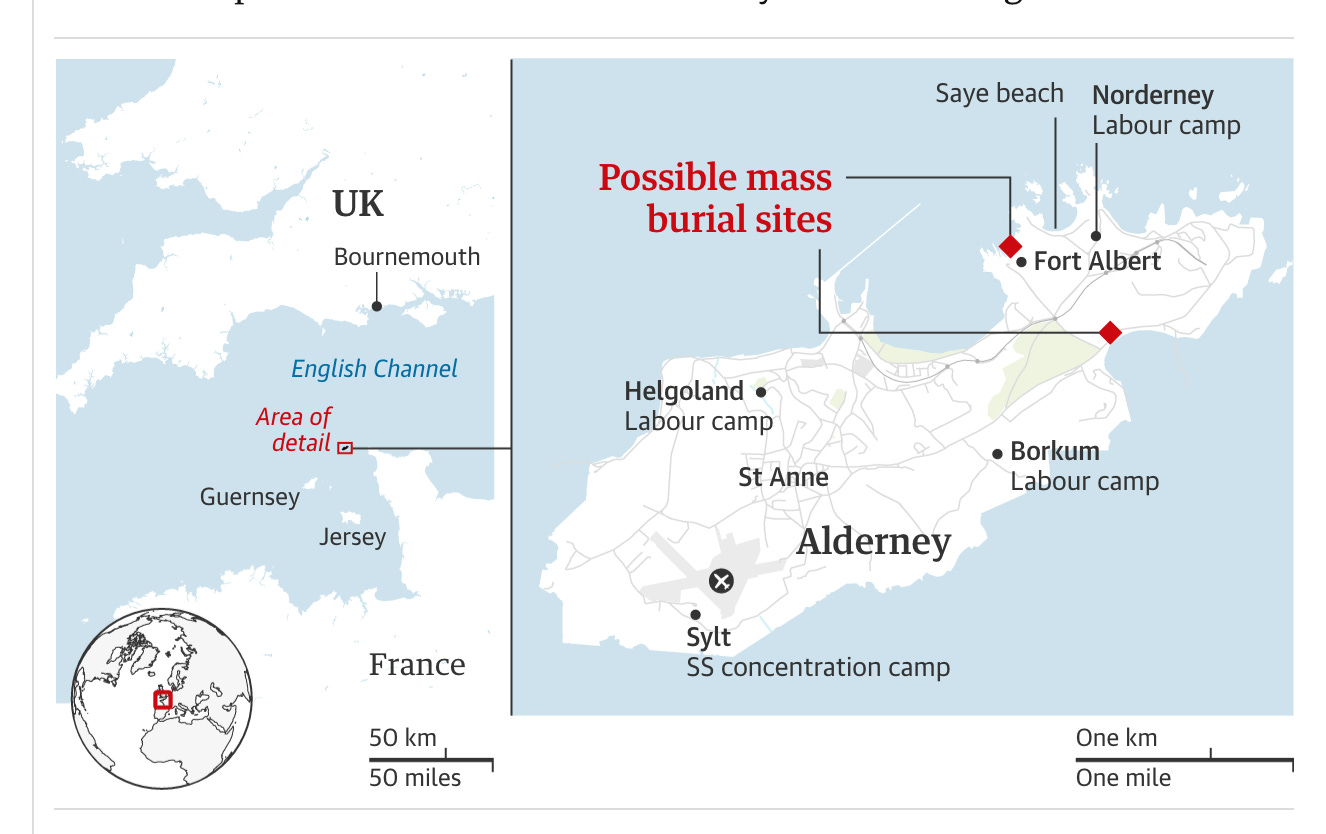

All four of the camps on Alderney were built by Organisation Todt, the Nazi construction organization. In 1943 two camps were handed over to the SS, one housed FrenchJewish inmates, the other mainly Soviet and Polish POW. They were administered as branch camps of the Neuengamme concentration camp complex.

Neuengamme was a concentration camp established in 1938 in the vicinity of Hamburg as a subsidiary of the better-known Sachsenhausen camp.

As historian Marc Buggeln explains the expansion of the camp system in 1938 was directly tied to the expansion of the SS interest in the construction industry:

On 29 April 1938, the German Earth and Stone Works, known by its German abbreviation, DESt, was founded by Arthur Ahrens and Dr. Walter Salpeter, who both had the SS rank of Sturmbannführer and would together play the role of official proprietors. However, the DESt was under the de facto control of Himmler and his chief administrator Oswald Pohl. Shortly after its founding, the DESt signed a contract with the General Construction Inspectorate on 30 June 1938, in which Speer guaranteed the purchase of 120 million bricks per year for ten years, for which the SS received an advance payment of 9.5 million Reichsmarks. After this, there was much hectic activity in the SS in order to start production of the construction materials. All plans were based on the exploitation of forced inmate labor. The new concentration camps Mauthausen, Flossenbürg, and Neuengamme were erected next to quarries and brickyards. Work there was hard and heavy. Therefore, even though inmate labor had increased in economic value with the growth of SS business enterprises after 1938, this did nothing to improve the situation of inmates—in fact, quite the opposite. The SS extended working hours, and with the outbreak of war, concentration camps saw a continual growth in mortality rates.

In 1940 Neuengamme had grown to such a size that it was granted independent status as a Stammlager with its own subsidiaries (Aussenlager). All told, by the end of the war, Neuengamme spawned 60 external camps - including those on Alderney. And another 24 for women inmates.

The proliferation of Aussenlager from 1942 onwards was tied to the agreememt between Albert Speer and Himmler for the use of concentration camp labour. After experiments with building production facilities inside concentration camps had proven expensive and inefficient, the decision was taken instead to build Aussenlager camps close to, or even inside the perimeter of factories.

Again Buggeln explains:

Himmler’s offer was that companies could build manufacturing facilities inside the main concentration camps and use inmates for labor. As a result, large production plants were established in concentration camps, such as the Siemens plant in Ravensbrück. However, industrial leaders and the German military found this arrangement unsatisfactory. They feared that the SS could gain control over the factories in the camps. Furthermore, the construction of new production plants proved burdensome. Industry would have preferred the opposite situation: instead of bringing the factory to the worker, bring the worker to the factory. In September 1942, Speer brought these proposals to Hitler, who then agreed. Speer and Hitler’s agreement laid the groundwork for building a system of subcamps, as external branches of the main concentration camps. These new subcamps would now be established directly on business premises, or in the immediate vicinity of a workplace. Until late 1942, there existed roughly 80 subcamps. Just one year later, in late 1943, the SS had set up 186 subcamps throughout the entire area controlled by the Germans. However, it was not until supplies of civilian forced laborers from the occupied territories began to dwindle that forced labor using concentration camp prisoners gained sweeping importance for wartime efforts to complete large projects. In the spring of 1944, due to the retreat of the Wehrmacht from a number of occupied territories, Sauckel had to admit that only a small fraction of the number of forced laborers originally anticipated could be supplied. From the spring of 1944, this led to a rapid increase in the number of subcamps built. In June 1944, there were 341 camps; by January 1945, the number had grown to at least 662 subcamps, despite the considerably reduced amount of territory under German control. The rising number of subcamps was accompanied by a sharp increase in the number of inmates. The Concentration Camp Division of the Economics and Administrative Department of the SS (Amt D, WVHA) registered 110,000 prisoners in the late summer of 1942; by the summer of 1944, this number had grown to 524,826 detainees; and in January 1945, the camp population reached 714,211 prisoners, of which 202,674 were female.

This passage is worth quoting at length because it spells out what we know to have been the driving logic behind the concentration camp system from 1942, its proliferation and scale. And it makes clear how absurd it is to imagine that two camps on Alderney, an island off the shore of France would have been the final destination for a considerable number of prisoners, when their labour power was so urgently needed in the Reich.

The list of Neuengamme’s Aussenlager shows Alderney with an inmate count of c. 1000, placing it in the middle of the rankings of 84 separate sub-camps.

As a concentration camp, Neuengamme was a detention, punishment and labour camp. Outright and immediate extermination was not its normal business, neither in the main camp, nor in the dozens of Aussenlager. The overwhelming majority of its inmates were not Jewish.

In the second to last column, the table below gives the number of inmates of all major concentration camps other than Auschwitz. The estimated number of deaths is on the far right. Majdanek had a higher death toll than inmate population because it combined extermination and concentration camp facilities.

According to the Neuengamme memorial site.

Almost 100,000 people from all over Europe were imprisoned in Neuengamme concentration camp between December 1938 and April 1945. Around 80,000 men and 13,000 women were registered by the camp’s administration and given a prisoner number. Roughly 1,000 Soviet prisoners of war kept their POW numbers and status. 1,500 people in police custody were registered with special numbers, while another 1,400 people were sent to Neuengamme concentration camp to be executed and were therefore not given prisoner numbers. … According to certified figures, at least 42,900 prisoners of Neuengamme concentration camp were killed. Of these, 14,000 prisoners died at the main camp, and 12,800 or more died at the 80 or more satellite camps. At least 16,100 prisoners lost their lives during the last weeks of the war on the evacuation marches, in collection camps or in the bombing of the prison ships in the Bay of Lübeck.

If the Aldernay camps exhibited the same mortality as the rest of the Neuengamme system, then we would expect c. 430 victims, which is very close to the official figure recorded by the British on the island. The camps only operated until 1944, but as Panovka has established, the rations available on the island were miserable, which would account for a high rate of mortality. In the worst period, in 1942, wen the concentration camp system was flooded with inmates and rations were cut to minimal levels, the death rate at Neuengamme approached 10 percent per month. Conditions subsequently stabilized, then deteriorated again sharply in 1945.

As a concentration camp, Neuengamme was one part of a ramified system of labour camps ranging from dormitory facilities for foreign workers, forced labour camps, POW camps, labour reeducation camps, concentration camps and their external facilities and death camps.

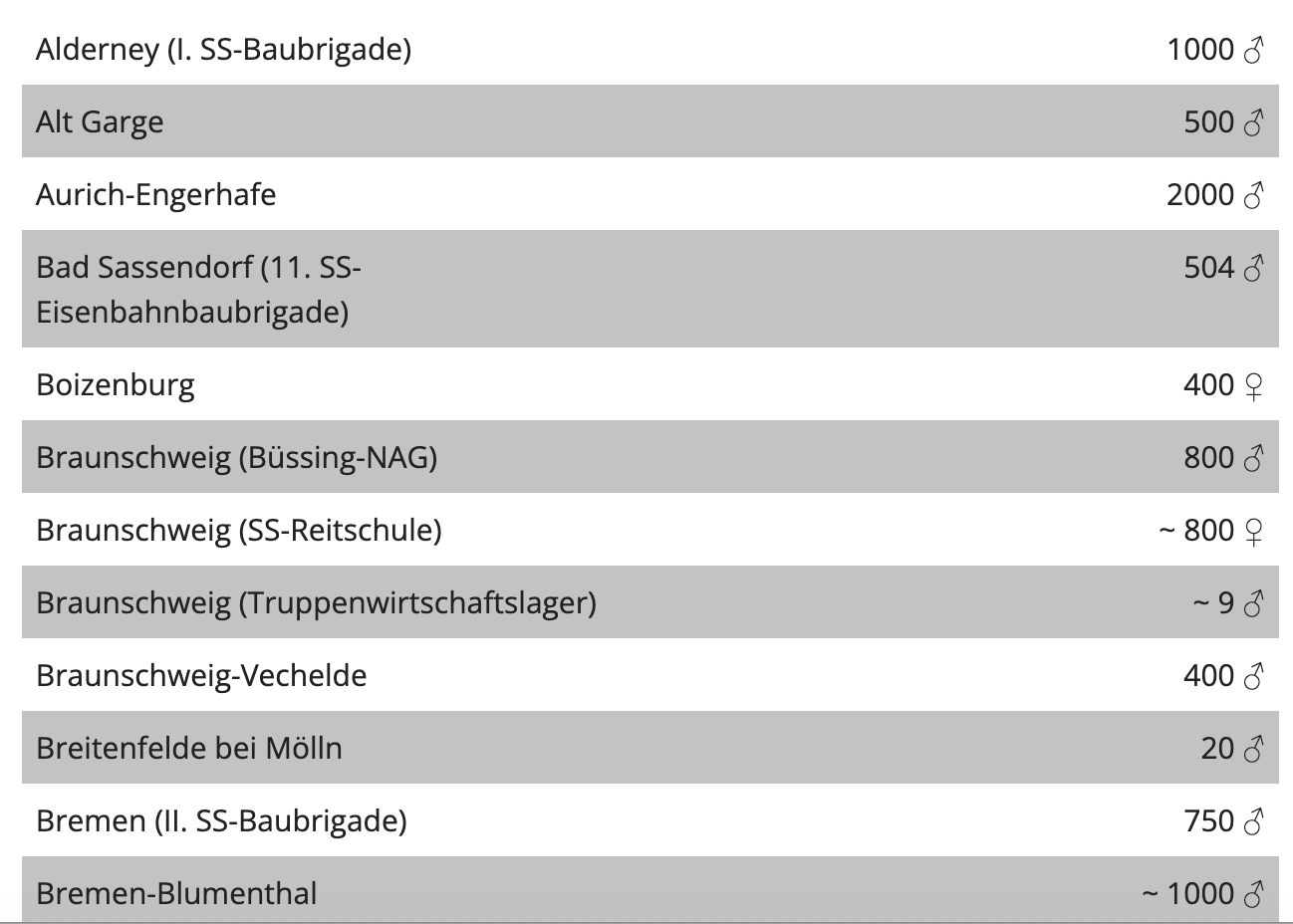

Thanks to the work of two generations of historians since the 1980s and the effort triggered by the slave labour law suits of the 1990s we have a pretty good idea of the quantitative outlines of this complex. Spoerer and Fleischhacker in 2002 established the most useful system of distinctions between different categories of workers. Using Albert O. Hirschman’s distinction between exit and voice, they differentiate between voluntary foreign workers, who could exercise both exit and voice, foreign workers and Western POWs who had voice but no possibility of exit and the category of “slaves” - Polish and Soviet POWs - who had neither. Finally, concentration camp inmates and “working Jews” were subject to a regime of mistreatment that made them “less than slaves”.

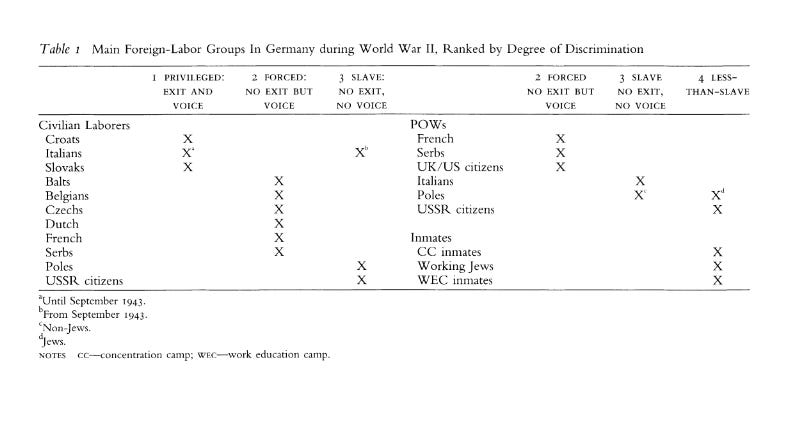

Spoerer and Fleischhacker provide estimates of the total workforce mobilized in each of these major grouping and of the numbers that survived, allowing us to estimate mortality.

It may be surprising that in this table, concentration camp inmates like those in the Neuengamme system had the highest mortality, even higher than Jewish workers. This is due to the fact that the Jewish workers counted in this data were either “privileged” German Jews or Hungarian Jews selected for work in 1944, when the Nazi war economy was actually desperate for labor and some effort was made to keep people alive long enough to make use of them.

In this reckoning, there are no millions of unaccounted for workers or victims. We have a reasonably accurate idea of how many people worked for the Nazi war economy and died and were done to death. The crime was gigantic. It beggars belief, but it was not beyond enumeration. It had a scale we can quantify and a shape we can map and diagram.

In Nazi Germany’s foreign and forced labour program - as distinct from the extermination program directed against the Jews, or the occupation, exploitation and colonization regime across Europe - out of 13.5 million people who were drafted for work in Germany, somewhere between 2.1 and 2.5 million died and were done to death, of which concentration camp inmates and POWs account for 2.2 million. The vast majority of those deaths occurred in large scale concentration camps in Germany and industrial Aussenlager not on far away islands in the English channel.

**

The racial war waged by Hitler’s regime was not a simple totality driven by a single ideological logic, that could express itself in any location, however improbable, in mass killing - allowing one to “discover” a British Holocaust on the Channel Islands.

Nor can the Nazi race war be adequately described by reference to a single site of killing - Auschwitz - or summarized in a single object, like a cattle truck, or a can of Zyklon B.

The Nazi racial war was a complex, structured assemblage/agencement - “a term that refers to the action of matching or fitting together a set of components (agencer), as well as to the result of such an action: an ensemble of parts that mesh together well” (DeLanda).

Given how sub camps like Alderney fitted within this violent and dynamic assemblage of labour mobilization and coercion, it is implausible, even allowing for the incompleteness of the records, to suggest that the number of casualties on the island could have exceeded the low thousands. To imagine otherwise reveals a basic incomprehension of the phenomenon one is supposedly commemorating.

The channel island was a horrible, but small site of death. To reach this conclusion is not an act of disrespect, let alone denial. Rather the contrary. It is only by precise analysis, of the type sketched here, that we do justice to the complex and murderous reality of the Nazi regime.

And this has implications beyond the study of the Nazi regime.

If we are to understand the working of power, it is this kind of analysis that we need: retracing, mapping, interpreting and translating the mechanisms, procedures, connections, technologies and diagrams through which agencies are assembled. And in so doing we perform more than just a cognitive, scholastic function. Gesturing to and denouncing the horror of modernity - aligning Auschwitz and Hiroshima - is no doubt a kind of politics. It is a politics of protest. It marks out an oppositional attitude. If we want to go beyond that oppositional pose, to something more political, to a politics of power, then our ambition must be recursive. We must go beyond gesturing towards power and its many appearances, from spectacular demonstrations to “Potemkin ducks", to actually diagraming its operations. We must get inside it. We must diagram power’s diagrams.

***

If you like reading Chartbook Newsletter, consider becoming a paying subscribers. It is generous contributions from readers like you that keep the project going.

Applause for Adam Tooze’s call for serious history of horrifying events.

great to read careful history vs sloppy journalism