Chartbook 267 JET-P: The "Paper Tigers" of Western climate geopolitics (also Carbon Notes #12)

"If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck”, then we all know what follows. “It probably is a duck." But that is the easy case. What if “it” looks like a duck and quacks like a duck and the resemblance is not skin deep, but as authentic as duck-like appearance gets, but, for all that, the beast does not swim like a duck, or fly like or duck or lay eggs like a duck, or taste like a duck. What to make of a “Potemkin duck”?

**

At the global climate conference in Glasgow (COP26) in November 2021, the hosts, the British government and their allies in Washington and the G7, were determined to put on a show. Glasgow saw the unveiling of what was, up to that point, the most comprehensive “answer” given by Western elites to the question of how to “mobilize” financial resources for the global energy transition. COP26 focused heavily on ending coal. After the embarrassing failure of COVID-management, which encumbered the conference in facemasks and mass testing, COP26 was a welcome opportunity to demonstrate leadership.

The big driver of financial mobilization announced at COP26 was an initiative catchily dubbed GFANZ - the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero - headed by none-other than, Mark Carney fresh from the Governorship of the Bank of England and now trumpeting a coalition capable of bringing $ 130 trillion to bear on the climate crisis. As the press release declared:

These commitments, from over 450 firms across 45 countries, can deliver the estimated $100 trillion of finance needed for net zero over the next three decades. To support the deployment of this capital, the global financial system is being transformed through 24 major initiatives for COP26 that have been delivered for the summit. This work has significantly strengthened the information, the tools and the markets needed for the financial system to support the transformation of the global economy for net zero.

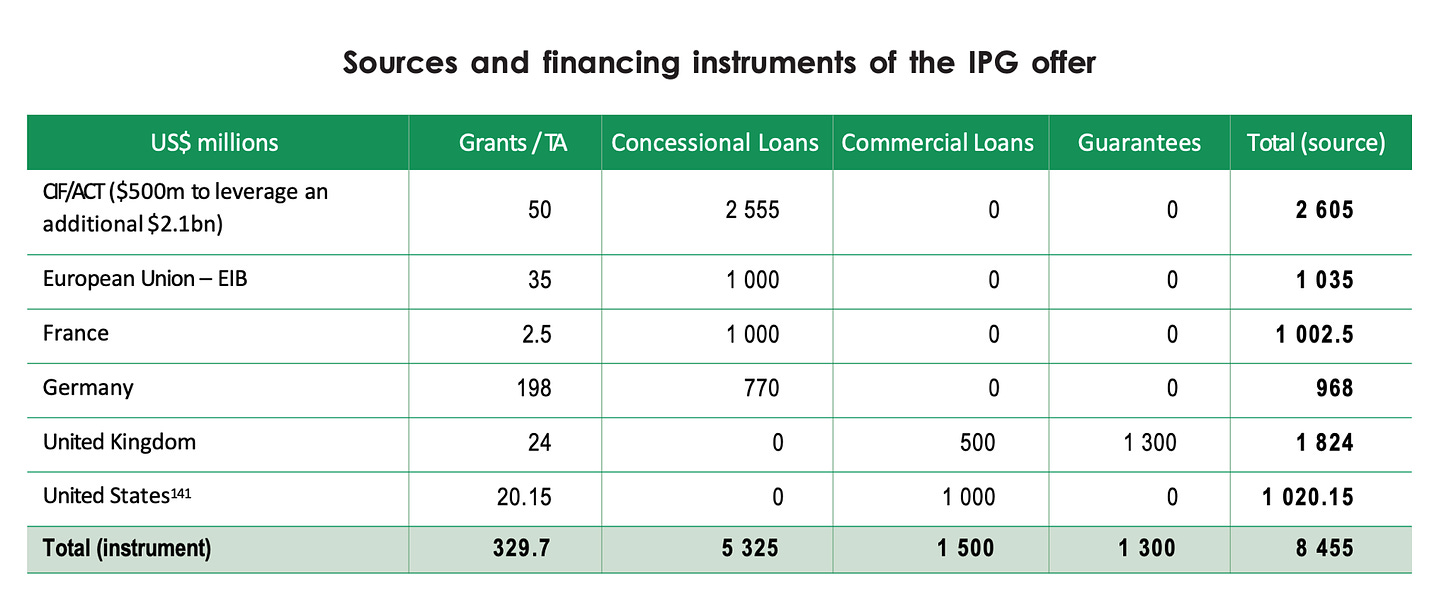

If GFANZ was the hammer, the scalpel of the global energy transition was to be a new kind of partnership between rich sponsor countries and key players in the developing world. Entitled Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JET-P), these multilateral deals were to have high-profile political backing. They were to target foreign funding at key obstacles on the energy transition path in particular developing countries. They were to be flanked by socially equitable measures to ensure that all key constituencies were taken along. The first of the JET-Ps was to involve the United States and a coalition of partners supporting South African efforts to reduce dependence on coal with $ 8.5 billion in outside funding.

The partnership with South Africa was not accidental. Thanks to its coal-dependent power grid, South Africa is the 14th largest CO2 emitter. The ANC leadership and South Africa’s many NGOs have long been closely engaged in global climate politics. In 2011 South Africa hosted COP17 in Durban. South Africa desperately needs an energy transition. The electricity system that developed out of the late phase of Apartheid is chronically crisis-ridden. Chartbook Carbon Notes 4 traced the genealogy of South Africa’s permanent electricity emergency. In 2021 South Africa’s embattled government boldly anounced that it would aim to close almost all its coal-fired power stations by 2050.

The JET-P announcement with South Africa has been followed by programs for Indonesia, Vietnam and Senegal. Insofar as we can speak of a “hot new” thing in the area of “climate finance”, since 2021, the JET-Ps are it. For the Biden administration, the EU and Japan they are the calling card.

But after the fanfare of 2021 and 2022, what have the JET-Ps actually amounted to?

At the end of 2023, in time for COP28, the performance of the JET-P to date was the subject of two reviews, one by Nicholas P. Simpson, D, Michael Jacobs and Archie Gilmour of the ODI, in the UK, and another hosted by the Rockefeller Foundation.

The two reports are very different in tone and style. The ODI report offers a critical quasi-academic review. Rockefeller reports on its 6 high level “convenings” in a glossy package with carefully worded and anodyne conclusions. The Rockefeller review also comes with a press package that garnered a write up in the FT from which one could glean something about the general tone of the Rockefeller meetings but little of substance.

And this is indeed the question of anyone digging into the reality of the JET-P. What exactly are these widely touted and seemingly ambitious, but also mysteriously empty policy programs? If these are to be important policy instruments for addressing the global energy transition, how should we interpret their obvious inadequacy? What does it mean to call something a duck that may look like a duck and quack like one but neither flies nor swims?

***

On the face of it, the JET-Ps are serious business. As the Rockefeller report explains in rather anodyne terms:

A large gap remains between what the world aims to achieve on climate action and the pace of national transitions in practice, especially among emerging and developing countries. A lasting turn away from fossil fuels first requires rapid growth in the use of renewables. But for now, more than 90% of all increased spending in renewables is going into developed countries and China. Righting that imbalance and bringing clean energy to those most in need will require the creation of in-country ecosystems to help speed that transformation. That means working to build local expertise; strengthening institutions; engaging civil society, utilities, and regulators; establishing sound transition plans; and helping to bring in outside capital of all kinds. Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) are a promising political and financial innovation designed to address exactly this challenge. These arrangements between the International Partners Group (IPG) of donors and host countries seek to accelerate host country-led energy transitions. They combine leader-level political support with the provision of concessional capital, targeting near-term investments with an elevated focus on easing the transition for workers.

At least three things are worth pointing out about this narrative.

The first is that it is crucial to recognize the agency in the design of the JET-P of the recipient countries as well as the donors. This bears most directly on the first word in the title of the JET-Ps.

Nowhere in the world, developed or developing, is the energy question more politicized than in South Africa. And it was South Africa’s ANC government that insisted on putting the word “Just” in the title of the new scheme. If there is going to be anything like an orderly exit from coal in South Africa, it is going to need the consent of interested parties like the Trade Unions and it is their interests that that word gestures towards.

As one report notes:

As of 2018 a small South African think tank seeded and socialised a proposition to overcome the binding constraint of Eskom’s debt trap (the S African power utility). The newly appointed, reform-minded CEO of Eskom, André de Ruyter, adopted and adapted this idea. He cooperated with the presidency and engaged with development finance institutions and large donors. The proposition was for donors to provide concessional finance in exchange for decommissioning electricity plants that had reached retirement age, combined with compensations for those victimised by such transition. A modified version became the foundation of the JET-P.

The second point is that though the Rockefeller passage may seem anodyne, it actually presents a sharply skewed image of the world. When we say that 90 percent of all increased spending is “going into developed countries and China” this is true, but it obscures the true balance. As the most recent data show, in 2023 China alone accounted for 40 percent of all new green energy investment worldwide, followed at great distance by the EU and the US.

Investments in the energy transition worldwide in 2023, by leading country(in billion U.S. dollars)

Source: Statista

That huge gap between China and the rest, puts in focus the double challenge which the JET-P were designed to address from the side of their sponsors.

At Copenhagen in 2009 faced with the criticism of the global south and the refusal of either China or India at the time to join a global climate pact, then British PM Gordon Brown and Sec of State Hillary Clinton had tried to save face by promising to “mobilize” $100 billion in climate finance.

Over the decade that followed the rich countries miserably failed to deliver. And they failed not just on climate finance. They failed to deliver on sustainable development altogether. Meanwhile, under the One Belt One Road program, China was pouring finance into selected countries in the developing world, with no regard to sustainability whatsoever.

By the time COP26 convened in Glasgow, relations between China and the West were, to say the least, tense. By 2022 there would be talk of war. Against this backdrop climate finance took on a new aspect. As the ODI report notes with commendable frankness, the challenge of China was a key motivating force behind the JET-Programs. “This geopolitical aim was never stated, but it had been clear for some time that Western countries were concerned about Chinese political influence in the global South and wanted a counter-offer to the BRI.”

The International Partners Group, comprised of the United Kingdom, United States, France, Germany, and the European Commission, which is the basic coalition backing the JET-P is notable precisely for the fact that it includes close allies of the United States and excludes China, by far the largest provider of bilateral funding and the global leader in renewable energy investment and technology.

The China Daily may be an unabashed propaganda outlet, but the account of the genesis of the JET-P offered on its webpage by Yu Hongyuan and Wang Xinyu of the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies is certainly more frank and to the point than the obfuscation that frames the Rockefeller report.

“Club-style energy partnerships are viewed by the US as an important tool for it to regain its strategic dominance”, Yu and Wang remark. IAnd they go on:

Within the G7 framework, the US has promoted synergy between its Build Back Better World initiative and the European Union's Global Gateway strategy, Japan's Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, and the United Kingdom's International Investment Initiative. With the G7 finally establishing the G7 Partnership for Infrastructure and Investment (PII, G7) as a framework for the cooperation of developed countries as a whole with the aim of narrowing the infrastructure investment gap in partner countries, the G7 Environment, Climate and Energy Ministers Meeting in 2022 formally endorsed the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) launched at the 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a new form of national partnership to be adopted by the "PII, G7". France, Germany, the UK, the US, the EU and South Africa formed the International Partners Group and announced the launch of the JETPs. The G7 has also established JETPs with India, Indonesia, Senegal and Vietnam.

If this is the broad geoeconomic framing, the projected financial mechanics of the JET-P are inspired by the logic of “development finance”, which has been hegemonic since the early 2000s: relatively modest injections of public funds will serve to derisk and to catalyze much larger flow of private funds. This model was formalized by the Billions into Trillions agenda that crystalized around the World Bank in 2015.

All in all, from the donor side, the logic of the JET-Ps seems transparent. They are thinly veiled acts of Western climate geopolitics. Their inner workings are typical examples of what Daniela Gabor has taught us to call the Wall Street consensus.

But before we jump to conclusions, we should ask a further question: if it is true that the basic “logic” of the JET-P as strategies of power can be readily deciphered, does it follow that they are actually significant tools with which to act on the world, either with regard to the climate crisis or the geopolitical competition with China? Does this thing which looks and quacks like a duck, actually fly?

This is where the puzzle starts.

***

Though their mission may seems clear and the historical urgency is undeniable, neither the Rockefeller nor the ODI reports hail the JET-P as world-transforming success stories. Rather the opposite. The upshot of both the ODI and the Rockefeller reviews of the JET-Ps is that after two years in the spotlight it is not in fact obvious that there is a “there there”.

For all the fanfare, in the last two years nothing substantial can be attributed to the JET-P, no major investment programs or major social packages, no substantial shift from coal to renewables and no significant political capital gained. As the ODI teams remarks “ none of the JET-Ps has so far generated concrete plans for how they can contribute to the ‘just’ element”. Rockefeller’s consultations yielded the sobering conclusion that:

“The theory underpinning JETPs is that they support political leaders in host countries to address domestic political-economy constraints by providing cheap and catalytic capital to invest in strategic projects, while also addressing the human cost of exiting from fossil fuels. As no projects have yet been financed under JETPs, the consensus view of stakeholders, experts and practitioners is the evidence to validate this theory is currently lacking.

Reading the excellent review of the first two years of South Africa’s JET-P by Jan Vanheukelom for ecdpm the Rockefeller judgement may be a little harsh. €600 million in concessional loans do seem to have been transferred to the South African Treasury by Germany and France. But no further finance has been forthcoming.

Like the ODI authors, Vanheukelom refuses to say that the JET-P are merely hot air. But clearly the main effect of the JET-P has not been, as advertised, to pit rich country support against key bottlenecks in the South African transition. The main benefit of the exercise so far has been to impel a sophisticate internal South African negotiation about the options. As Vanheukelom argues, South Africa’s JET-P is first and foremost domestically driven with international partners playing a modest role, at most.

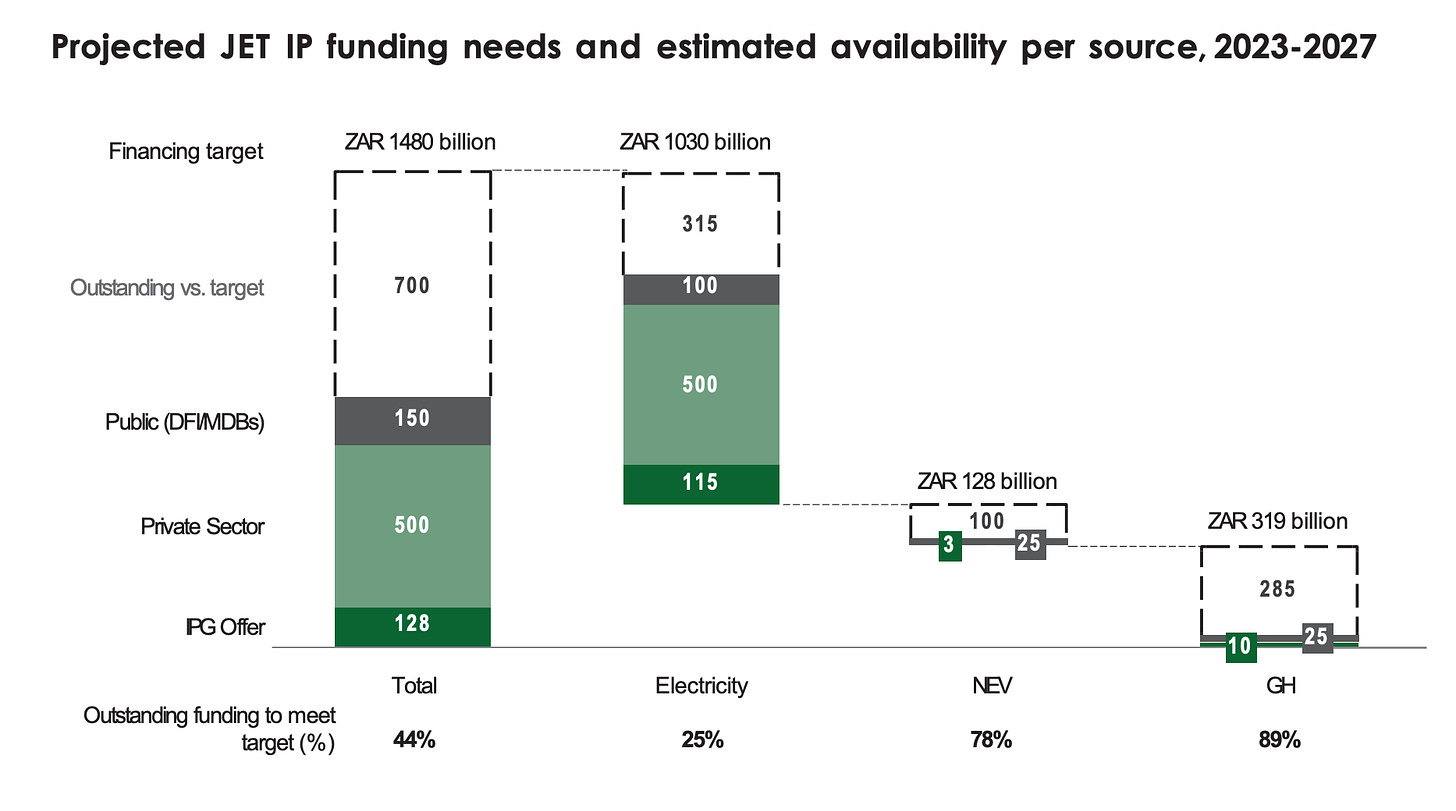

If we look at the overall pattern and structure of JET-P funding, it is not hard to see why the role of the external partners is so modest and the results on the ground so hard to find. As the ODI report stresses, the energy transition is a complex and laborious business. It requires policies to be assessed over very long time periods. But no less obvious is a basic mismatch between means and ends. In relation to the scale of the challenges facing major emerging markets and developing countries, the financial backing for the JET-P is plainly insufficient.

A tiny share of the funds allocated is in the form of grants. Much of the money appears to be rebadged funds that were already allocated. Broadly speaking the funding for both South Africa and Indonesia’s JET-Ps is one tenth of what is required.

Not only are the JET-Ps underfunded, the vision of the transition around which they are designed is lopsided. The Glasgow agenda was all about phasing out of coal. That provoked a protracted argument with India. A preoccupation with coal certainly fits the South African case. But in the developing world at large, the desire to shut down highly polluting coal-fired power plants can often appear as a perverse Northern plan to reduce power supply to populations that already have far too little power. For most of the lowest income countries closing coal-fired power stations has no relevance since they have precious little generating capacity of any kind, whether coal or not. For this reason the Senegal program, though notionally a JET-P, has little in common with its three predecessors.

As Rockefeller observes, the JET-P programs are not so much a generalizable model as a series of ad hoc offers dictated by expediency. After South Africa made a start, Indonesia got a program to jolly up its chairing of a high-stakes G20 meeting in the autumn of 2022. Vietnam, is in the frontline of the China containment strategy. In 2022, Egypt launched a JET-P equivalent on the occasion of its hosting of COP.

But beyond these cases, there is no general process for other candidates. The Philippines is an example of a state in which the West is trying to counterbalance Chinese influence and in which Rockefeller has scouted opportunities for a JET P-style strategy, but it has so far not been considered for a plan. There is, in fact, no organization to which a JET-P candidate can apply.

And then, in each case, there are the problems on the ground. The transition is sensitive everywhere. Reports from Indonesia suggest an impasse.

The JETP has a good basic idea, which is for the U.S., Japan, and European allies to lead the way on Indonesia’s clean energy transition. But when we look at the sums actually committed, and the conditions under which they are being offered, a couple billion dollars in concessional and non-concessional financing and credit guarantees designed to catalyze a big wave of market-rate debt and private investment is not the only path forward here. Indonesia has made it clear the country is open to investment from all sources, but it has to be on terms that are sufficiently attractive and appealing to domestic stakeholders, and not just to foreign developers, lenders, financial companies, and the DFC.

Of course these obstacles weren’t lost on anyone involved with the crafting the respective national JET-P. If the energy transition were easy, the recipient countries would not need a partnership. The idea was to overcome entrenched fossil fuel interests, notably coal, with a targeted injection of aid and high-profile political commitment. But that requires scale and impact and that is precisely what the JET-P, to date do not deliver.

What South African experts said to me in candid conversations last year, was that the basic lesson of the JET-P was that they could not rely on substantial foreign aid would that they had to do the energy transition “for themselves”.

They have to do it because change is coming whether entrenched coal interests want it or not. In South Africa’s case the current situation of rolling power-cuts is clearly unsustainable. There are only so many times you can retreat to the dubious fortress of coal. The cost curves in favor of renewables are spectacular. The mine union in power utility ESKOM may have decided to oppose the JET-P. It represents 50,000 workers with a strong voice and a stranglehold on the existing, derelict system. There are 2.5 million people living in communities closely tied to coal mining. But South Africa is a nation of almost 60 million desperate for power. Renewables are the cheap future. As the Presidential Commission on Climate Change led by Crispian Olver has argued, not transitioning as rapidly as possible is not a formula for safely preserving the status quo. It is a formula for chronic and escalating crisis. The question is how you manage and distribute the sectional costs of this inescapable transition.

What the JET-P were intended to do was to ease this bargain. But with inadequate funding they deliver little or no actual relief. So what, one is left wondering, are these policy packages for?

If it looks like a duck and quacks like a duck but does not fly or lay eggs, if it is not actually an aquatic bird, what is it?

***

We must credit the authors of the JET-P programs and their staffs as highly competent experts. But precisely if that is the case, they cannot intend the JET-Ps either as a serious counterweight to potential Chinese influence, or as an adequate contribution to the challenge of sustainable development. We can all agree that either would require a substantial commitment of money, which so far is not forthcoming. No one in Washington can believe that with $1 billion the US can make a significant impact on a problem as complex as South Africa’s energy transition.

Of course the hope is that public money will catalyze private investment. Blended finance promises to mobilize private funding on favorable terms. A cynical analysis might suggest that profit-seeking by Western financiers is the ultimate motive for the JET-Ps. Extending the ambit of private finance provides a comprehensive rationale for global action. But though public-private partnership is at the core of Western financial systems, when it comes to the wider world, the actual sums of money mobilized by derisking and blended finances are simply too tiny to weigh heavily in the balance. No significant contribution to Wall Street’s profits will be made by the few billion that the Biden administration has mobilized for global climate finance.

You might say that the JET-Ps were gestures that were intended to foster good will with their recipients. But what are South Africans to make of a situation in which the national power system is breaking down, the carefully budgeted program for sustainable reconstruction comes in at $98 billion and the offer is $8.5 billion of which less than a billion are grants. Only a small amount of that funding can in practice be used to offer first-loss derisking and the mobilizing potential for private finance is minimal. It is true that in the last year offers have increased. But they raise the total to $11.9 billion. Little wonder that the South Africans are led to turn inwards.

In the Indonesian case the discrepancy is no less glaring. The total investment required is in the order of $96.1 billion by 2030, compared to $11.5 offered in public funding of all kinds, which comes with strings. The amount of derisking actually offered by the Indonesian JET-P is minimal. As the ODI report comments;

in the Indonesian JET-P the pledges of concessional finance from IPG members are already primarily allocated to improve the enabling environment and project preparation facilities, and little remains to de-risk and attract private finance from GFANZ members.

The net result is not to build mutually supportive international networks around the JET-P, but rather the reverse. Patently inadequate funding makes the donors look unserious. It undermines their standing as good-faith actors and encourages cynicism. Furthermore, assuming that the policy-makers in question are serious people, they cannot be surprised by this result.

So this sharpens the question, what purpose is served by rigging up these insubstantial and inadequate programs that cannot be taken seriously as real tools of power?

The obvious explanation would seem to be that though the individual groups of actors on the donor side are all rational and serious-minded, they are rational and serious-minded in their own way. The policy-making process in the West is relentless, but it is also polycratic, incoherent and it feeds first and foremost on its own outputs. It is, if not entirely closed, highly self-referential.

Expert policy-makers in Western capitals feel that they have to make a response to major historic challenges like climate or the rise of China, or South Africa’s energy crisis. It is their job to look to the future and to devise at least purportedly rational strategies of power. But those who make policy on such matters as sustainable development do not hold the purse-strings and have limited capacity to shift budget-constraints. Those that do set budgets, either do not care about broader global issues, prefer other tools for affecting those goals - such as military power - or are revenue constrained and unwilling to levy more revenue from their constituents for the far-flung goals favored by the policy-making elite.

There is thus never “enough money” for the softer and more complex dimensions of development and global policy. But, despite these all too obvious limitations, the policy-machine grinds on. Faut de mieux those tasked with geoeconomic policy and sustainable development cooperate to come up with programs like JET-P. The policies tick all the boxes as far as sophistication of design and conception. Powerful interests - notably high-finance - ensure that they are arranged, at least notionally, so as to offer derisking and to promote the vision of public-private partnership. The promise of “mobilizing” private money helps to paper over the lack of solid public funding.

But despite all the self-interested engagement by private finance, the fiscal constraint remains paramount. The forces interested in global development are not as powerfully engaged as they are around the military-industrial complex, oil and gas or the Wall Street nexus. The result are ambitious and professionally designed policies that whip up waves of enthusiasm in the ranks of analysts, think tanks, NGOs, pundits, but which have no prospect of materially affecting reality either with regard to the announced policy objective or the profit opportunities of Western capital.

***

How then do we read a policy program like the JET-P?

From experience since 2021 the conclusion we must surely draw is that the one interest that such policies undeniably serve is the perpetuation of the policy circuit. Practical effectiveness is not necessarily the main driver of policy-generation. Indeed, failure may be productive in generating new policy. This not only perpetuates the machinery of policy-making. More importantly it contributes to the generation of a “state effect” - the US has a policy for x,y,z. It sustains the common sense that the world is governed and that “governance” is in some sense a coherent process.

It would be crudely nihilistic to claim that this is all that policy does. Undeniably there are some state-led interventions that do shape history. But clearly all policies do not. In general policy discourse has an oblique relationship to the distribution of coercive, persuasive or material power.

At the same time, if it is true that the policy-making processes have theirs own interests and logics, these, clearly, are not autonomous. They do not exist in a vacuum and impose themselves on the world from above or from the outside. More often it is interests and ideologies in the world beyond the formal boundaries of government that shape the policy-making process, as highlighted by the pervasive influence of the Washington consensus and the Wall Street consensus.

But, again, as the Jet-P illustrate, conformity to the prevailing ideological script is no guarantee that conforming policies will have significant real world impact. Only the first level of critical analysis can, therefore, content itself with showing how policy designs conform to certain ideological scripts and schema. The next question has to be, are they Potemkin villages - facades conforming to a certain narrative rather than more substantial interventions? As projects of power do they offer, for instance, offer a real challenge to China. Or, as Mao Tse-tung once said about American imperialism, are they“Paper Tigers”?

If Paper Tigers is all that they are, we should not shy away from that conclusion. But we should follow it up, with the next obvious question. What does it tell us that programs like the JET-P are both so precisely conforming to what we take to be the prevailing script (on climate, China and public-private finance) and so inconsequential?

It tells us that one segment of Western elites is bought in on the diagnosis of global crisis and global challenges like sustainable development.

That same segment wishes, especially on occasions like the COPs, to appear to be in the business of ordering the world in a progressive manner.

At the same time, other interests at the center of power are not willing to back those visions of global ordering with funds or other resources of power. They prefer either to withdraw from global ordering, or to do so indirectly by way of dollar dominance, energy supplies, or by the heavy handed means of global military power.

Private finance appears in many situations as a convenient partner. It is important in closing the gap between governmental ambition and limited fiscal means by gesturing towards the “mobilization” of private funds.

Elites in the emerging markets and developing have their own reasons for accepting the empty promises of the donor countries.

The result is a configuration - one might say “equilibrium” - that can give the impression of a coherent system of power and ideology. That coherence and apparent hegemony makes a tempting target for critical analysts of power to tilt against.

In fact, that coherence and “conformity to script” disguises a fundamental mismatch between the ends and means of power, between ambitions and resources, rooted in the failure of Western elites to agree how, if at all, to face the scale of global challenges. This is both a problem of elite incoherence and the difficulty of rallying mass support for expensive solutions.

The result, as far as the ambitions of global sustainable development are concerned, is not a highly profitable mechanism for the benefit of global finance, or a high-functioning mechanism to propel humanity into a sustainable 21st century, but vacuity.

Given the forces at work in the world, this “equilibrium” is highly unstable, prone to crisis and progressively delegitimizing for all involved.

What Crispian Olver of South Africa’s Presidential Climate Commission described as his country’s status quo, might be said of policy more generally: “we muddle along, we continue to obfuscate, we delay, we’re behind the curve as the world economy moves…”. And, at some point, a duck-looking thing that quacks but neither flies, swims nor lays eggs, is no longer a duck.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

May I ask for a heading every 6 to 10 paragraphs to articulate the text? I pay for this newsletter but I am busy. You don't have to take only my opinion, ask other people as well.

Since we don't have an executive summary to this flow of consciousness narrative, I would attempt one:

- Duck joke

- COP26 is global effort,

- JET-P about lower financing for south africa/indo

- Rockfeller and ODI review it, say it does not do anything

- JET-P is actually a trojan of G7 against China

- JET-P is not funded, and does not do anything

- it seems to be policy for the sake of policy, so it is just performative

- Duck joke

Did I miss something?

Thanks for holding the West to account on climate change. As I think you once commented, Western liberalism is beset by hypocrisy.

And the Potemkin duck isn’t just found on sustainable development. Where are the people who pontificate about “responsibility to protect”? There is a genocide happening in full view. Why not declare a no fly zone” over Palestine? Where is the responsibility to protect? It seems the Potemkin duck has stopped quacking over the genocide happening in Gaza.

The question I have is this: why has the Munich Security Conference and all such other “security conferences” ignored the genocide? All the IR experts that pontificate about China should hang their head in shame. China is doing more to uphold international law than anything the IR advisers have managed to accomplish. Shame on you hypocrites.