Carbon Notes 4 From Feast to Famine: Apartheid's power bonanza and the genesis of South Africa's electricity crisis.

Envisioning the global energy transition there is a credibility gap. Expert modeling says that trillions of dollars in investment are needed every year. $ 4 trillion per annum globally and $ 1 trillion for the Emerging Market and Low-income world ex-China is a substantial but feasible share of global GDP. But why, given the track record to date, would low-income and developing countries believe that funding and support will be forthcoming?

To date, levels of support from the rich world are an order of magnitude off. And though the IRA and Green Deal have kicked green industrial policy debate in the global North into a new and higher gear, this debate seems entirely preoccupied with the China-USA-EU triad. Furthermore, the subsidy race between the rich countries may, in fact, imperil the energy transition in the Global South.

It was this jaundiced backdrop which gave strategic significance to the announcement at COP26 in Glasgow in November 2021 of the Just Energy Transition Partnership between the United States, European partners and South Africa. With proposed funding of $8.5 billion it seemed finally to offer an answer to the question of how the rich world and the developing world might cooperate in the energy transition.

As Sierd Hadley comments at ODI.

For South Africans, the JETP potentially offers financial support for the challenging energy transition, a precondition for revitalising the economy and creating much-needed jobs. There is currently no other mechanism which would unlock the scale of international public finance needed to retire South Africa’s multiple coal-fired power plants, re-skill fossil fuel workers and support local economic development in coal mining regions. For South Africa’s development partners, the JETP offers a relatively low-cost way to rapidly cut emissions and stimulate private investment in clean energy, electrification and other green technologies

Faced with the scale of the challenge and the limited progress so far, it is not too much to say that “the eyes of the world are on the JETP”. It fills a large hole in the narrative by which the global elite convinces itself and its audience that the energy transition is manageable and realistic. The model’s appeal has been confirmed by the fact that agreements labeled as JETPs have since been extended to Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt and India.

The selection of partners is telling. Thanks to global growth it has become more and more clear in recent years that climate politics must extend beyond the familiar boundaries of the G7 - USA, EU, Japan - and China. The largest part of global emissions and the most rapidly growing part is in the statistical box once labeled ROW or “Rest of the World”. India’s annual emissions now exceed those of the EU. Indonesia’s emissions are the fifth largest in the world. South Africa, Africa’s only member in the G20, has the 14th largest emissions in the world. Vietnam is one of the most rapidly growing economies and has hitherto been very heavily dependent on coal.

Nor is it a coincidence that South Africa was the first to partner with the EU and US in a JETP. Thanks to its coal-based electricity and heavily energy-dependent mining sector it has per capita emissions almost on a par with Germany. It is unusual amongst middle-income countries in having been heavily involved in climate politics for a generation. It has a rapidly expanding renewable sector, which accounts for 10 percent of electricity generation and since 2020 it boasts a Presidential-level commitment to crafting national climate policy.

It was in 2011 at COP 17 hosted by South Africa in Durban that the concept of just transition was first introduced, by COSATU the South African trade union movement. It is a coinage that befits a country with South Africa’s profile. It has been said that South Africa has the emissions profile of Australia and the inequality of Mozambique, a combination which starkly reveals its history - an amalgam of the overlapping trajectory of colonial and inter-ethnic struggles across the Southern cone of the African continent and the model of extractive capitalism common to many settler colonial regions, be they Australia, Canada or the United States.

And more than the numbers are at stake in this JET partnership. South Africa today still carries the nimbus of the anti-apartheid struggle. The Mandela generation is gone. But the senior leadership in South Africa today, were young activists in the 1980s and 1990s. Today that same elite and their collaborators preside over a society and polity confronting huge social problems, of dramatic inequality, mass unemployment, social discontent and a precariously balanced political economy, which under Jacob Zuma between May 2009 and February 2018 lurched alarmingly towards kleptocratic state capture.

In addition South Africa faces something very unusual, the progressive collapse, extending over a period of more than 15 years, of a once sophisticated and reliable electricity network. South Africa’s electricity utility Eskom has become a byword for dysfunction with rolling blackouts and a near permanent state of emergency in the power sector. Meanwhile, growth in South Africa is measured not in double digits but in fractions of one percent. The current forecasts for 2023 range between 0.5% (World Bank) and 0.1% (IMF). This is well below the rate of population growth even in a society experiencing rapid demographic transition.

For some of the broader backdrop check out the podcast.

In South Africa, the polycrisis is real in the most dramatic and urgent form.

In March 2023 global reinsurers let it be known that the triple impact of the pandemic, the extensive looting during the 2021 “Zuma riots” and heavy flooding in 2022 had caused them to triple rates for catastrophe insurance for South African clients. Even before this current rash of disasters, South Africa ranked fifth in the world in terms of total insurance premiums as a percentage of gross domestic product and accounted for a staggering 70 percent of all insurance premiums in the African continent. Now some insurers, “either on their own initiative or at the urging of reinsurers”, are notifying South African clients that their policies will not cover the event of a total power grid failure, a contingency which is a matter of daily conversation the length and breadth of the country.

So the JETP is not just a complicated scheme for international financing of renewable energy development. It is an intervention in a country that is widely seen, both inside and outside, as standing at a fork in the road. To put it rather dramatically the question is: Can a just energy transition unlock growth? Or will the energy sector, organized in Moloch known as Eskom, drag South Africa into a doom loop of economic stagnation, interest group in-fighting, social dislocation and violence.

Given this dramatic backdrop,, a lot of reporting about South Africa of late has been dominated by lurid stories of poisoning attacks on the Eskom boss, sabotage, organized crime and illegal mines operated by migrant labour from Zimbabwe. It is telling that De Ruyter the now-ousted boss of Eskom, told one reporter that he viewed his embattled years at the company “‘as my second diensplig,’ …. referring to the mandatory military conscription of young (White) South African men during the apartheid era”. Kyle Cowan continues in his book Sabotage published in January 2022 by Penguin Press: “It is easy to see why (De Ruyter) feels this way: he and his team are at war. And the battle lines are not traditional; the other side are using guerrilla tactics and are apparently well versed in the dark art of destabilisation.”

Rather than espouse this disturbing view of power system management as counter-insurgency, I want in this newsletter to try to tell the South African energy story in terms of political economy. This political economy, of course, bears the imprint of South Africa’s trajectory from the apartheid to the post-apartheid era, but its chronology and logic also reflects more general trends in the governance of capitalism around the world and familiar dilemmas in how to organize and plan for investment in energy systems shaped around the economic imperatives of the mid to late 20th century. The way this is shaping up, this is going to be a multi-part story. Part 2 will deal with the Ramaphosa government and the 2021 Jet P. In this first part I want to try to sketch a narrative of the multiples forces that define South Africa’s current situation as a highly electrified, deeply modern society deeply engaged in global climate politics but also one on the edge of total power failure.

In making this sketch of the South African power crisis, I draw selectively on a dauntingly vast and sophisticated literature on South African political economy. One of the fascinations of South Africa to an outsider is the sheer sophistication and contentious multiplicity of narratives it produces about itself. Eskom is no exception. This newsletter is a first effort to wrap my head around this hugely complex field. In doing so, I owe a debt to everyone I had the privilege of talking to on a recent trip to South Africa. In particular I owe thanks to the wonderful Keith Breckenridge, whose recent essay “What happened to the theory of African capitalism?” I recommend to your attention. I want to thank WISER at Wits University and the Wiser-Standard Bank chair in African Trust Infrastructures for their support of my trip. I had. ahugely stimulating time in the company of Murray Leibbrandt and the brilliant audience at ACEIR at the University of Capetown.

Whatever I did manage to learn, I owe to these interlocutors. The errors are all mine. If you know a lot about this, please feel free to let me know where I am going wrong.

***

Part of the tragedy of the current moment is that as recently as twenty years ago electricity in South Africa was a success story with global resonance. Eskom was hailed as one of the best utilities in the world. This was in part the halo effect of the post-apartheid era. But it also reflected a dramatic story of change, for the better.

Electrification in South Africa began as early as 1882, impelled by the power needs of the mining industry and cheap coal. From the outset, electrification bore the imprint of a hotly contentious polity. Escom (the forerunner of Eskom) was set up in 1923 to provide the railway system with a power supply that was not under the control of syndicalist White working-class local governments. Escom would go on to position electrification at the heart of what Ben Fine and Zavareh Rustomjee dubbed South Africa’s “minerals-energy complex”.

According to McDonald in his edited collection Electric Capitalism, in the 1990s mining and minerals accounted for 40 percent of electricity consumption in South Africa. Conversely, electricity, even at heavily discounted tariffs, accounted for 32 percent of the intermediary costs of gold production. It takes 600 kwh to yield one fine ounce of gold. As a result, South Africa’s economy was estimated to be three times more electricity intensive per unit of gdp than the USA.

For its first sixty years, Escom in Apartheid South Africa was first and foremost an industrial power supplier, which also provided electricity for white domestic consumers largely by way of private distribution companies.

Capacity grew dramatically through the mid-century, but by the 1960s Escom was struggling to keep up with the demands of the booming South African economy. A break point was reached in 1970s as the South African apartheid regime faced the oil crisis, the escalation of the Cold War on the African continent in Angola and Mozambique and the Soweto uprising of 1976. The strategists of Apartheid began to fear what they called a “total onslaught” that would require the South Africa state to defend a last redoubt of white rule. For the power sector, as Andrew Lawrence argues, the implication was that Escom needed to dramatically increase capacity - to a gigantic total of 70 GW by the year 2000. A key element of this expansion drive was the nuclear power plant and weapons program at Koeberg. South Africa thus offers and extreme and ideologically-overdetermined example of electricity expansion planning at the time. Such dramatic expansion programs, often with a nuclear component, were not unusual in the 1970s and 1980s.

In South Africa the investments of the 1970s and 1980s continued to shape the available generating capacity decades later. The last of the big 1980s projects was Majuba Power Station on which work began in 1983. Its last unit came into operation in 2001. At that point, Eskom had effectively doubled the available generation capacity to just under 40 000 MW. It was also the halting point for any further expansion.

By the mid 1980s the horizon of expectation had shifted again. With the South African economy beginning to slow under the impact of sanctions, forecasts for future demand began to seem excessive. Power tariffs, imposed above all on household consumers and small businesses, who took their power from regional and municipal distributors, were rising fast. Meanwhile, industrial consumers continued to be supplied with power at favored rates. The White voter base were disgruntled. In 1983 a commission of inquiry under Dr W.J. de Villiers recommended sweeping financial and operational reforms including the merger of the entire electricity supply industry into a single system, renamed Eskom rather than Escom. New plant construction was halted - a ban that would effectively remain in place until 2004.

The management of the newly formed Eskom began looking for new sources of demand to absorb the capacity they were constructing. They did so against a spectacularly uncertain horizon. The one thing that seemed obvious was that the Apartheid status quo could not last. As Pieter du Toit outlines in his remarkable book, The ANC Billionaires. Big Capital’s Gamble, faced with a mass popular uprising and facing exclusion from the world economy, South Africa’s big business interest began to look for an escape from the impasse of apartheid. At Eskom, Dr Ian McRae, who was appointed CEO in 1985 entered into clandestine contact with the ANC to explore options for expanding power supply to townships. Contrary to the racist legends of the regime, which denied the very idea that Black South Africans might use electricity, McRae found a huge repressed demand for electrical services.

Across the political break of 1994, the drive to expand mass consumption of power would shape Eskom’s history. Mass electrification of South Africa’s townships, it turned out, was the logical complement to the capacity expansion triggered in the 1970s by fear of a black “onslaught”.

Between 1991 and 2014, in the forefront of the National Electrification Program, Eskom would provide new electrical connections to 4.3 million households. That is almost a quarter of South Africa’s 15 million households. As a result of combined action by the ANC-led government, Eskom and local authorities, the share of households with power rose from 58 percent in 1996 to 87 percent of those in formal housing by 2013. At that point three quarters of informal shanty settlements had power connections too. From 2003 universal connection was encouraged by the introduction a basic ration of 50 kwh per month in free electricity for every household with a meter.

It is this expansion of electricity supply, which defines the crisis of power supply as it is felt across South African society today. The impact is all the greater for the fact. that the vast majority of homes are actually connected.

But the politics of electrification were always more complex than this celebratory story of expansion suggest.

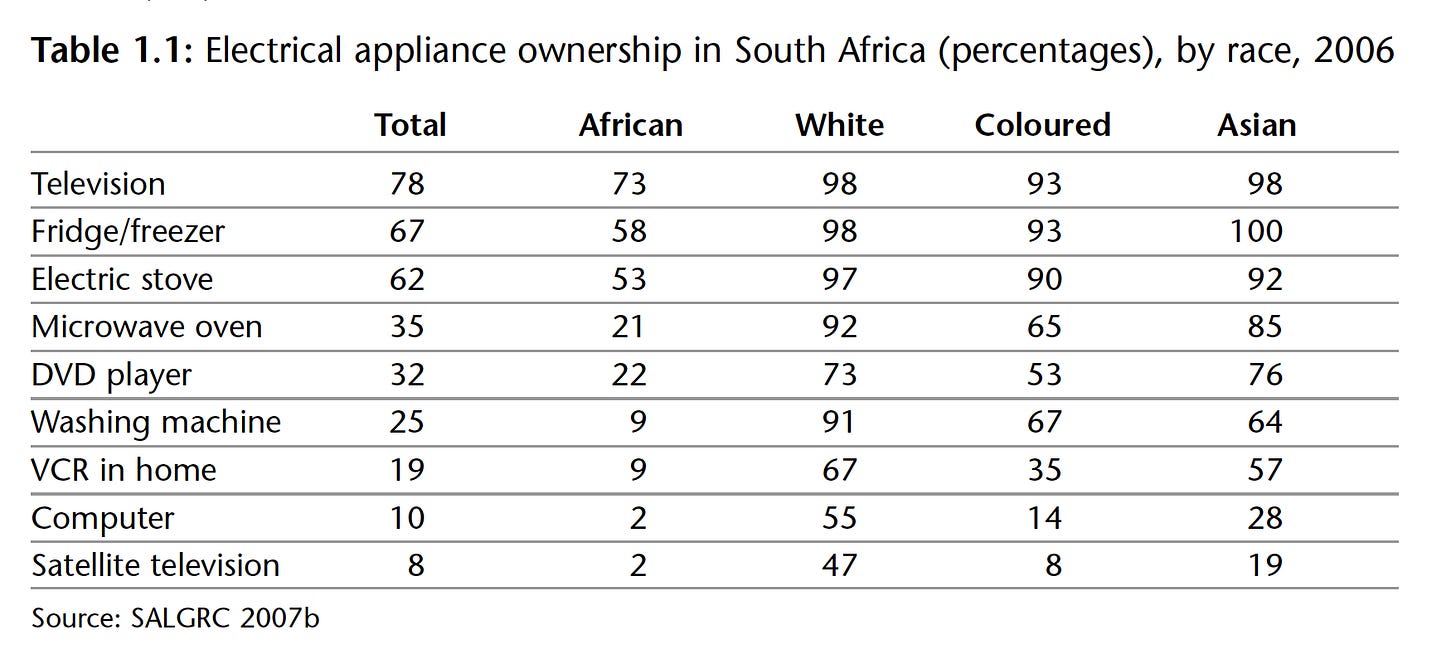

The most obvious question is who actually gobbled up most of South Africa’s power. Even allowing for mass electrification, low-income households accounted for no more than 5 percent of demand (McDonald Electric Capitalism, 16). Consumption per household remained extremely modest, in most cases barely rising above the 50kwh that were provided free per month from 2003. Penetration of consumer goods was defined by the extreme inequality of South African society and sharply demarcated along racial lines.

To substantially tilt the balance towards consumers would require South Africa to achieve true mass affluence, a dream which remained far out of reach. The biggest beneficiaries of the power bonanza bequeathed by the apartheid-era expansion were industrial producers. In the 1990s and 2000s with the global resource boom in swing, South Africa’s abundant and cheap electricity made it a major investment location for aluminium production, stainless steel and ferro alloys. The coega aluminium plant owned by Alcan of Canada and then snapped up by RioTinto was to be one fo the biggest smelters in the world attracting huge South African subsidies as well as GW of power.

The rates for this group were negotiated between Eskom and the so-called Energy-Intensive Users Group. The amounts paid were rarely made public in the 1990s and early 2000s but there is reason to believe that they were extremely favorable to the business users. This is not by itself unusual. Favored rates for major customers are commonplace. But the contrast is particularly egregious in the South African case because of the degree of inequality and the way in which that was openly articulated in contractual relations between Eskom and its customers.

Eskom’s mass electrification drive was based on the innovation of prepayment. Crucially, this ended the system under which retail customers paid for monthly delivery in arrears - effectively owing the utility for a month of supply. That required customers to be creditworthy, a level of confidence that might be extended to the members of the EIUG or a privileged white household under Apartheid, but clearly did not extend to black households in the townships. What unlocked the supply was flipping the risk so that customers made prepayment to their accounts for the electricity they were going to use. In effect hard-pressed consumers extended an advance to Eskom not the other way around. Unsurprisingly this made supplying them more attractive. As critics pointed out, Eskom retained the power to end supply as soon as the cash ran out. What ought by rights to be a social entitlement was turned into a commercial relationship governed by household budgeting.

It was, in short, an individualized, market-based, low-trust relationship typical of contemporary, neoliberal thinking about service provision. However, the meaning of that relationship depended not only on how it was formally structured. It depended also the terms of trade on which consumers and producers interact in the market, on the price. And in that regard at least the 1990s and early 2000s were kind to both Eskom and its customers. Taking advantage of the apartheid-era capacity surge, electricity was cheap. Tariffs were progressively reduced to some of the lowest rates in the world. And under those circumstances, whatever the form of the supply relationship, it was hard to see electrification as anything other than a blessing.

***

Given the ANC’s founding commitment to socialism, and its close ties to the Communist Party and the Soviet bloc during the years of struggle, South Africa’s post-apartheid conversion to a neoliberal model of economic governance was spectacular. In fiscal and monetary policy this was encapsulated in the adoption of the so-called GEAR agenda. In the electricity system, thinking ran along similar lines.

In 1998 the White Paper on electricity proposed extending neoliberal visions to power supply. The White Paper proposed that Eskom be separated into two parts: the transmission system that would remain a monopoly and the generating side which would be thrown open to competition. This was the model of unbundling pioneered in Chile and the Uk in the 1980s and 1990s and that went on to be adopted by over 100 countries worldwide. The idea being that it disaggregated decision-making on price-setting and investment thus minimizing the risk of big mistakes and lowering costs to minimum.

On paper the unbundling vision prepared for South Africa by PwC looked good. It seemed like an obvious way to maximize competition in what might otherwise be seen as a natural monopoly sector. But like any other structural change it was a gamble. Crucially, it was not clear whether such a system could really provide incentives for long-term investment. Experience with unbundling in Uganda and Kenya gave little grounds for optimism. In South Africa the powerful trade union COSATU and Eskom management opposed the unbundling plan. In 2003, under substantial political pressure, Mbeki’s government abandoned the idea. Private investors who had been gearing up to enter the market were left jilted at the altar and more importantly, Eskom and South Africa were left without an investment plan and time was running out.

Throughout the 1990s ESKOM reserve capacity was well above the 20 percent threshold considered comfortable. It was on this basis that corporate interests at Eskom and national electrification neatly aligned. But already in 1998 forecasts were warning of trouble ahead. By 2008 at the latest Eskom would need more capacity if the happy balance of corporate and societal interests was to align. But, distracted by the brawl over the abortive “unbundling” plan and hoping to be able to rely on foreign capital, the Mbkei government stalled any new investment. ESKOM improvised by bringing back online plants that had been mothballed years earlier. This maintained the momentum of electrification, but only postponed the eventual reckoning.

Not until September 2004, after the battle over privatization and decentralization was fought out, did Eskom and the South African state face the need to begin making serious plans for major new investment. With diversified private source of supply off the table, Eskom reverted to a gargantuan version of 1970s and 1980s-style power planning. The basic idea was to add two giant coal plants, rated at almost 5 GW each, plus new nuclear reactors. Longer-term, the required investment was put at close to one trillion rand.

Work on the giant Medupi power station began in May 2007. But the soonest it would be operational was six to seven years in the future, a very optimistic forecast it turned out. To expand capacity quickly, Eskom added two smaller, more flexible open cycle gas turbine stations, at Gourikwa and Ankerlig. Completed in short time frames between 2006 and 2008, they brought online just over 2 000 MW with which to meet peak demand. The downside was that they ran on expensive diesel fuel.

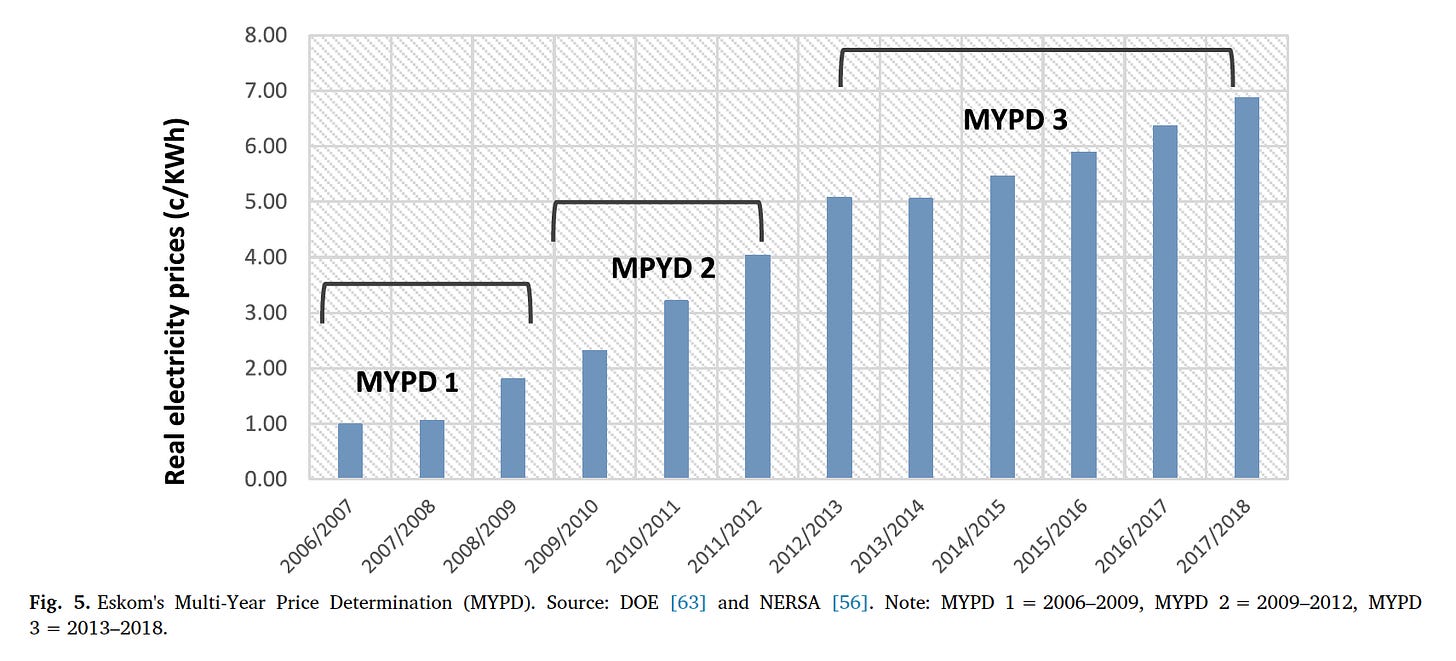

As in the 1970s capacity expansion brought with it the question of financing and that raised the issue of electricity pricing. In the early 2000s though it was neither unbundled nor privatized, ESKOM was corporatized meaning that it was converted into a free-standing, publicly owned corporation which paid dividends to the South African state. The quid pro quo in 2006 was a change to ESKOM’s pricing formula, which was notionally designed to align prices more closely with generating costs. With the approval of regulator NERSA, ESKOM would confront its vastly expanded customer base with a series of price escalators, structured as Multi-Year Price Determination (MYPD).

The good years in which cheap power would fuel social and economic development were coming to an end. But it was far from obvious that the window of opportunity in the 1990s and 2000s had been long enough for South African society at large to grow to the point at which it could easily bear substantial increases in the cost of electric power. Average incomes were up but the vast majority remained so poor that even minimal electricity prices were likely to be felt as punitive.

***

And, then, before ESKOM could put in place the new regime of greater investment and price increases, disaster struck. Starting with a failure at the Koeberg nuclear power station at the end of 2005, South Africa’s over-stretched electricity system began to fall apart. From November 2005 rolling blackouts and load-shedding became a daily reality.

The blackouts were caused not by an absolute shortfall of capacity below demand, but by a lack of safe reserve capacity to deal with inevitable outages. From a high of 27% in 1999 the margin of reserve capacity had fallen by late 2007 to a dangerous 5 percent. At that point any outage in the system required load shedding. Outages occurred with increasing frequency not only because the power stations built in the 1970s and 1980s were getting old and worn out, but because maintenance had been underfunded and Eskom had underinvested in training and motivating its workforce. Furthermore, reliability problems were compounded by a shift from established relationships with large-scale coal mining companies which were often excessively favorable to the mining companies, but at least secured regularity of good quality supply, to a new network of smaller black-owned mines, whose supplies were haphazard and of lower quality. Eskom compounded the complexity of its situation by shifting a share of its coal contracts to a spot market basis.

In November 2007 a new series of power cuts began and by early 2008 Eskom and the government were forced to declare a national emergency. Mining output plunged as did business confidence. Electricity had tipped from being one of the success stories of South Africa to being a driver of panic. Nor was there any real question about the basic source of the problem. On 11 December 2007, during a fundraising dinner in Bloemfontein, Mbeki admitted: ‘When Eskom said to the government: “We think we must invest more in terms of electricity generation”, we said no, but all you will be doing is just to build excess capacity,’ ‘We said not now, later. We were wrong. Eskom was right. We were wrong.’

Mbeki had been struggling for years to maintain the grip on power of the relatively conservative centrist wing of the ANC. Six days after his Bloemfontein speech, his time ran out. Jacob Zuma, former head of the ANC’s counter intelligence wing, who had been ousted by Mbeki in 2005 as his vice president on corruption charges rode to victory at the ANC’s national elective conference in Polokwane. In 2009, after a brief interim period, he was carried to power on the back of an upsurge of left populist indignation at the failure of the post-Apartheid era to fulfill the promises of 1994.

***

Given Zuma’s subsequent career and the extent to which he serves as a symbol for all that is “wrong” or might “go wrong” in South Africa, it is important, at this point not to flatten the narrative. We know what happened next. State capture and kleptocracy would come to the fore and Eskom would be at the heart of it. But that turn for the worse was not immediately obvious in 2008.

On the most existential question facing South Africa at the time, HIV/AIDS, Mbeki’s ouster finally brought a turn to a more rational policy. Mbeki had taken a lethally misguided line on HIV, blaming the disease on poverty. His successors promised to do more to address poverty, but they also ended AIDS denialism and introduced the mass provision of retrovirals, saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

The ESKOM crises of 2006-2008 and Mbeki’s ouster also marked the opening of a new era in the politics of climate and renewable energy in South Africa.

South Africa’s first renewable energy plan had been drafted in 2003. But it was not until 2009 that the government hosted a nationwide conference on renewable energy in Pretoria. At the COP conference in Copenhagen in November 2009, South Africa’s government committed itself to reducing emissions by 34 percent by 2020 and 43 percent by 2025 - ambitious targets. South Africa’s intensified engagement with climate, set the stage for the Zuma government to host COP17 in Durban, where South African diplomacy played an important role in restoring momentum following the disaster of Copenhagen and where the South African trade union movement would launch idea of “just transition”.

Meanwhile, South Africa’s energy regulators and the Department of Energy came to see renewables as a potential solution to the power supply problem. The coal investments that Eskom was pushing for since 2004 were hugely expensive. Funding was uncertain and the 2008 financial crisis increased the pressure on South Africa for economy. In Europe, Germany, Spain and Italy were demonstrating the possibility for affordable rapid deployment of solar. In 2009 the NESRA, South Africa’s regulatory agency, took the lead in introducing a feed-in tariff - known as the renewable energy feed-in tariff (Refit) - along the lines that Germany had pioneered. Feed in tariffs are a model under which independent generators or households with solar panels on their rooftops are allowed to sell surplus power to the grid at an advantageous rate, encouraging decentralized investment in renewables.

The 2010 Integrated Resource Plan envisioned that by 2030 20 percent of South Africa’s power would come from wind and solar. 40 percent would be from low-carbon sources. This kind of planning was also significant in that it reflected the sense that with the victory of the left-wing of the ANC over Mbeki, there might be a return to more concerted economic government.

When NERSA’s Refit initiative fell foul of administrative institutional conflicts, the renewables push did not end. Instead, Department of Energy replaced it with a new program under the amended Electricity Regulation Act (ERA) that allowed private sector renewable developers to bid for supply contracts. After intensive informal consultation with the business sectors including investors, lawyers and the financial sector, the Department of Energy in August 2011 launched the program know as Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme (RE I4P). This was to provide for contracts to cover 17.8GW of new renewable energy generating capacity by 2025, which would go a long way to towards bolstering ESKOM’s reserve capacity.

It appeared, in short, as though the combination of a global developments in climate policy, technological change, the local energy crisis and the lurch to the left of the South African government would open the door to an acceleration of the energy transition and a green solution to the Eskom crisis. Over the following years that hope would prove to be premature. Renewables, climate and the energy transition were now on the South African agenda as never before. But progress was painfully slow and at times seemed to be going into reverse. Meanwhile, South Africa suffered a lost decade symbolized by Eskom’s spiraling into near total failure.

***

This sense of dithering on the threshold to a new energy system, had local determinants of course. But it is a chronology familiar from Europe and the US in the same period, where after an initial burst of optimism around 2008, which for instances saw the Obama team advocate for the first Green New Deal, progress stalled. The money for subsidies in the US ran out. Against the backdrop of the Eurozone crisis, European renewable investment plunged.

In South Africa the fossil fuel interests around Eskom - as opposed to the Department of Energy and NERSA - fought back hard. And they gained support from the outside. In 2010 in a controversial decision the World Bank gave its approval, worth $3.75 billion in loans, to Eskom’s giant Medupi coal-fired power plant, one of the two projected since 2004 and one of the largest coal-fired stations ever built outside Asia.

Quite apart from environmental and climate impact, this cemented ESKOM’s ruinous commitment to implementing a giant investment program which its staff had no experience of managing. For a notional budget of R150 billion it planned to build not just the 4 764 MW Medupi plant, but the 4 800 MW Kusile coal-fired stations, plus the Ingula pumped storage scheme in the Drakensberg, which would deliver 1 332 MW of hydroelectricity during peak demand periods. Medupi and Kusile would end up costing three times as much. To this day, they have not reached full capacity. Funding needs far exceeded the World Bank loan, leaving Eskom hugely in debt. To keep up its payments it was forced to raise electricity tariffs at an extraordinary rate. In real terms between 2006/7 and 2017/8 Eskom’s customers would see electricity prices increase sevenfold.

This was all the more egregious because privileged industrial consumers like BHP were paying substantially less than the cost of generation. In addition South Africa’s long-suffering consumers had to deal with ever more frequent and serious outages.

Starting in 2013 electricity supply became chronically unreliable. As the new coal-fired power stations failed to come online and costs soared, ESKOM ran its existing generator stock to the point of collapse, whilst skimping systematically on maintenance. The overall impact was to stop dead in its tracks the growth in demand for power, which had been at the heart of the upbeat story of electrification up to 2006. South Africa shifted from being a society in which energy use was broadening and deepening to one in which economic growth depended on economizing on overpriced and unreliable electric power. Richer consumers resorted to buying their own generators. But industry was prevented from expanding so-called “embedded” power production by rules that barred connections for anyone generating their own power. It was a hobbling, unproductive, inefficient disaster, which helped to constrain South Africa’s lack-luster economic growth. GDP per capita stagnated in line with power consumption for most of the 2010s. Perversely, low growth helped to cap power demand on Eskom, cementing the low-level equlibrium.

***

So far in this account I have not given prominence to the drama of Zuma’s Presidency, corruption on an epic scale, kleptocracy and state capture. This is not to deny their significance but to make the analytical point that the combination of capacity constraints, badly managed construction projects, deteriorating infrastructure, low-level inefficiency and a fierce upward ratchet in prices is, by itself enough to explain a severe deterioration in South Africa’s power situation. And it was those factors which presumably most directly impinged on South African power consumers. But behind the scenes we now know that Zuma and his cronies were indeed engaged in a remarkable series of schemes which amounted not just to theft but to a complete subversion of the integrity of the state. This directly impinged on ESKOM because personal and family connections cynically cloaked in the rhetoric of Black Empowerment enabled the transfer of billions of dollars in assets. Padded coal contracts were one of the means through these deals were financed and vast sums of money were siphoned into corrupt channels that in turned helped to cement the grip of smaller-scale local mafias over coal supplies.

Though Zuma’s and the Gupta’s actions were shocking, rather than thinking of them in isolation as corruption or kleptocracy, it is perhaps more illuminating to think of them as being situated on a spectrum of mechanisms - limited neither to the market and formal contracts nor to formal politics and legislation and public administration - through which resources were distributed within the South African power system.

Zuma and the Guptas were clearly engaged in criminal self-dealing. That happened both at the national and large-scale and locally in smaller networks notably in the coal regions. Meanwhile, large power consumers benefited from extraordinarily advantageous deals that were never made public. As Lawrence reports:

In 2013, when the average generation cost to Eskom was about 40c/kWh and industry customers paid close to this amount, BHP Billiton, which buys 9% of Eskom’s electricity, paid only 22.65c/kWh, while 4.5 million residential customers paid on average R1.40/kWh—more than six times more.

One is put in mind of Bertolt Brecht’s famous quip: “What is the robbing of a bank compared to the founding of a bank.” Meanwhile, management and trade unions helped themselves too. They regarded Eskom as their bailwick which it was essential to defend against the intrusion of competition, alternative technologies and the reforming impulses of regulators or the Department of Energy.

Whilst Zuma’s large-scale corruption and local mafias centred their attention on coal, as far as the renewable energy transition is concerned it was bureaucratic politics that was more consequential in blocking the progress of renewables in South Africa after the promising starts of 2009-2011.

The shift in South Africa from the original idea of a generous feed in tariff for renewable energy towards a system of competitive auctions for contracts to deliver renewable power, was very much in line with international trends in the 2010s. Auctions were all the rage. But it was consequential not only because it prioritized large power producers but also because it shifted the balance of power within the energy supply system. The somewhat free-standing bureaucratic and expert unit within the Department of Energy (IPP unit) that was responsible for the auctions drove the process with real energy. Up to 2015, the DOE notionally procured almost 5GW from 77 renewable energy generation projects. Furthermore, across the four rounds of bidding, the price, especially for solar PV, came down so fast that it was able to match the costs of generation at the coal-fired mega-generators in Medupi and Kusile. But the entire process was stopped dead in its tracks in 2015 when Eskom’s management dug in their heels and refused to sign or finalize any further IPP agreements. Acting group CEO Matshela Koko gloated openly over his obstructionist stand. Eskom refused to free up budgetary space to purchase the power. In addition Eskom resorted to making prohibitive charges for grid connections. Rather than proactively expanding and strengthening the grid it used the fact that the existing transmission system was centered on the coalfields in the North East of the country to limit the expansion of solar and wind which are more naturally located in the North-Western side the Cape. Nor was this opposition confined to renewables. Eskom adopted a similarly obstructive stance towards power imports from both Namibia and Botswana too.

As one expert remarked: “Eskom frustrates the entry of IPPs and private investment through the disingenuous use of facts, the political brinkmanship and what lawyers term malicious compliance, through the quiet subversion of government policy by actions such as delayed access or inflated grid-connection costs for IPPs.” Beyond bureaucratic resistance Eskom also deliberately incited opposition from major trade unions – the National Union of Metalworkers of SA (NUMSA) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) - by threatening that taking up the renewable energy capacity would force it to hasten the decommissioning of five older coal stations. In reaction the NUM reacted by calling rolling mass strikes to block the adoption of private power supplies.

ESKOM’s own preferred solution to the capacity problem was to add a third major coal-fired power complex to the two that it was struggling to complete. Meanwhile in Zuma’s inner circle the favorite boondoggle was a plan to hurl $1 trillion rand at a 9 GW nuclear upgrade. Frustrated developers who thought they had won successful REI4P tenders took to the courts to force ESKOM and the DOE to proceed with the contracts as agreed. But it would take court actions at a higher level to really break the deadlock. It was the collapse of the Zuma Presidency over the winter of 2017/8, amidst a welter of legal claims, that would break the deadlock and allow the combination of external engagement and internal rebalancing that had first announced itself in 2009-2011 to begin again to shift South Africa’s power system. That is a story to be continued in a future newsletter.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Brilliantly researched and written. Having lived in SA and worked with ESKOM and Koeberg specifically throughout the 80‘s through the early 2000‘s, I have experienced firsthand the incredible work done by the very well educated and experienced personnel within ESKOM and their commitment to lead a world-class utility. Sad days to see what has happened since. Maybe there is still hope for a turnaround - see https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=be4vChJ3E1s

Adam, you have done your homework well! Having worked with both ESKOM and NERSA as an external advising basis during the 2000-2007 period you have brought back of flood of those memories with your piece. I hope you had the opportunity to meet with professor Anton Eberhard who has been working in power sector reform for the past 30 years or longer during your visit to UCT.

In my experience, ESKOM had the technical skill and personnel to make change happen. What they and the unions and government lacked was the ability and desire to change as you clearly articulated. ESKOM at its core was and is culturally and monopolist. Monopolists block entry and change for fear of loss of status or their jobs! The same is true with the unions. The fear of loss meant they’d hold on to coal for as long as humanly possible because of perceived job losses and social dislocation and encouraged by the unions, and because ESKOM lacked any imagination on operating any other kind of generating technology.

Add into it, my perception that if they allowed new generation to interconnect they would now have to think about the transmission system as a truly meshed network with power flows that went against their entire experience.

As somebody who has worked in power systems for more than 25 years, the ESKOM system operates radially like a hub and spoke network with the hub in the NE centered on the Mpumalanga coal fields and radiating out to from there with the longest lines reaching the western cape where Koeberg was located. When Koeberg went down, it was difficult to support power transfers due to long lines, lack of voltage support, and in reality was single point mode of failure if any of the transmission line tripped or were taken out of service.

Your mention of Zuma’s boondoggle on 9 GW of nuclear had its start in Eskom’s fixation with pebble bed nuclear technology that 25 years later still has not seen the light of day, and insistence on my 7 years of discussions was that it was just around the corner. We see the same today with modular reactor technology in the US. But given the fixation with “6 packs” or 6 600 MW unit coal plants and pebble bed nuclear, the imagination and innovation simply left the collective mind.

And while South Africa did not have meaningful access to natural gas, for years there was the possibility of gas E&P of the Atlantic coast off Angola and Namibia or Mozambique on the Indian Ocean side. Clearly nothing came of that and this the huge boom in technical improvements in efficiency and cost savings seen in gas turbine technology that started 20 years ago have passed the country by.

Finally, and maybe something for further exploration, is the outsize role that ESKOM played in the Southern Africa Power Pool (SAPP). You mention the imports from Namibia and Zimbabwe only in passing. At one time this was one of the more sophisticated power pooling arrangements in the world. Now it has become moribund. ESKOM had the coal, other countries had the hydro. There was once cooperation in operations and planning. And there were big dreams, that while nice on paper, would never be realized but this also stymied thinking beyond what was in front of ESKOM. They already had access to Cahora Bassa in Mozambique, though the colonial past surrounding it is not pleasant, and dreamed of tapping hydro potential in Angola (all they have gotten was good Cuban food, music and culture instead). Such projects are overly grandiose and avoid the hard work of manage power system planning, operation and control and doing what is feasible and needed in the short to medium term.

All this being said, South Africa and ESKOM need fresh, innovative thinking, toss out the old ideas, and begin thinking in the near term with no regrets as the point of departure for a strategy to get out of this mess. But the necessary condition is to change the political and corporate culture of ESKOM and the unions and get them to see their fear of loss will only beget further loss.