It is said that in the spring of 1945 the skies above Germany’s Ruhr industrial region cleared and the Rhine river ran blue for the first time in almost a century. British and American bombing had stopped the German economy in its tracks. Nature, briefly, healed.

In 2023 the skies above Germany were not clear, but the latest annual review by Agora Energiewende, the authoritative think tank that is the chief advisor on Berlin’s climate policy, reports that German national CO2 emissions fell by 20 percent relative to 2022. That is a 73 million ton reduction relative to last year, bringing Germany’s total emissions to 673 m tons of CO2 equivalent, the lowest level seen since the 1950s. Emissions today are 46 percent lower than when Germany was unified in October 1990.

A 20 percent fall in the CO2 emissions of an economy the size of Germany is significant by any standard. It is precisely the kind of slashing cut that we need to see if we are to have any hope of meeting the ambitious climate targets set for 2030 and 2050. The numbers refute the all too eager pessimism of the climate skeptics who declared that Putin’s attack on Ukraine and Germany’s quixotic exit from atomic power, would doom it to reliance on fossil fuels.

In fact, as Agora reports:

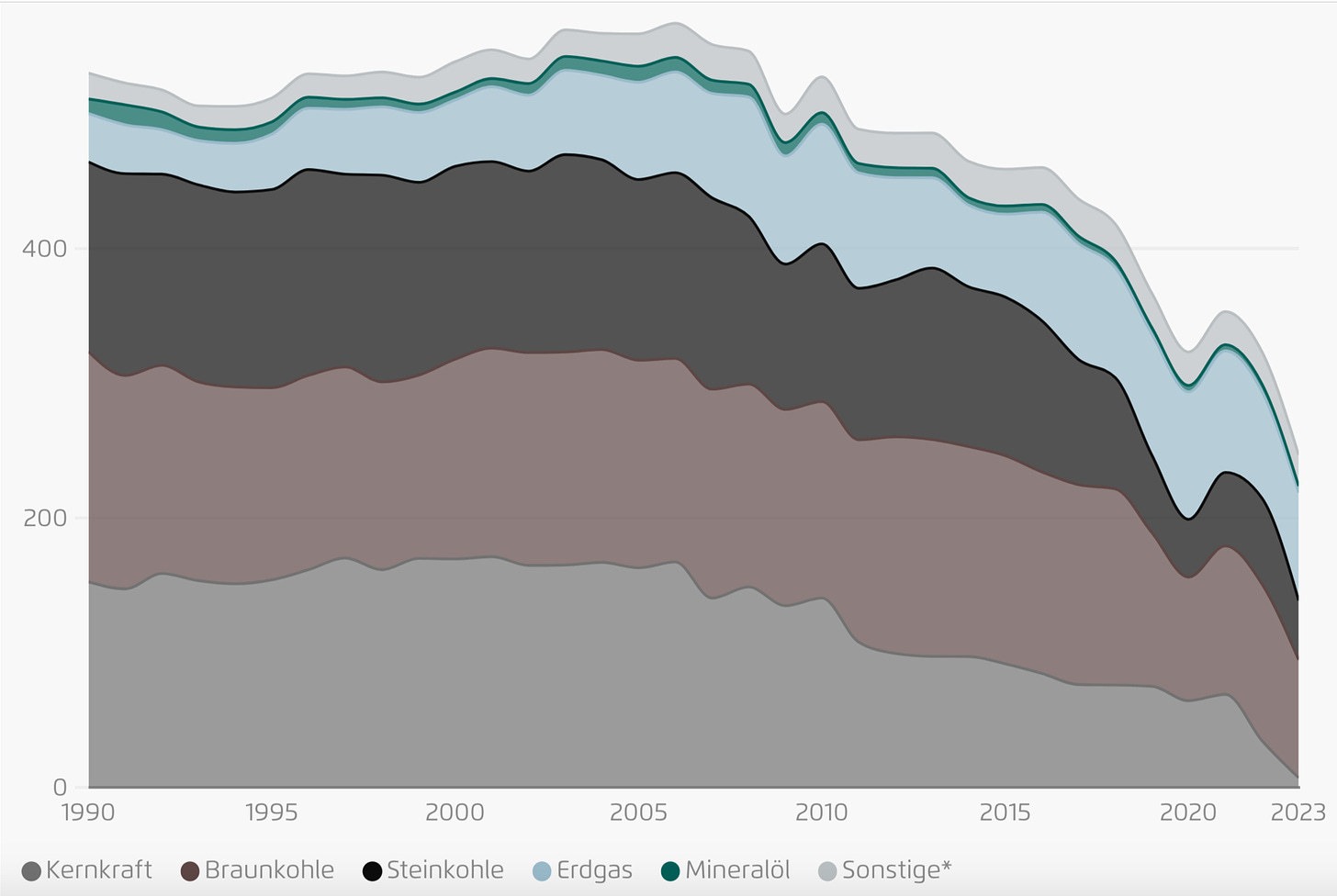

coal-fired power generation fell to its lowest level since the 1960s, saving 44 million tonnes of CO₂ alone. …

Landwirtschaft = agriculture, Gebäude = buildings, Verkehr = transport, Industrie = industry, Energiewirtschaft = electricity generation/power sector

The 21 percent drop in emissions compared to 2022 is mainly due to the sharp decline in coal-fired power generation: lower electricity production from lignite saved 29 million tonnes of CO₂, while hard coal-fired power generation saved 15 million tonnes of CO₂.

This is great news. It is completely contrary to those claiming that the war would force Germany back on coal.

Of course, if nuclear power generation had remained at its level of the early 2000s, Germany would now have no need to burn coal at all. But the nuclear exit decision was taken a generation ago and other than political troublemaking, nothing is served by wailing over spilled milk.

There is also some good news on the renewable energy front. Overall renewable energy production increased by 5 percent. For solar power in Germany, 2023 was a record year.

Record levels of newly installed solar capacity contributed to the drop in electricity prices: Germany added 14.4 gigawatts of photovoltaic capacity last year, an increase of 6.2 gigawatts compared to the previous record in 2012.

This means that Germany finally escaped the disastrous slowdown in solar installation that struck in 2013 under the second Merkel government.

Of course, it is not just capacity that counts:

Although there were fewer hours of sun in 2023, solar power facilities produced 61 terawatt hours of electricity – one terawatt hour more than the previous year. Photovoltaic expansion was therefore well above the target pathway for 2030.

And it was not just solar that contributed to Germany’s energy transition in 2023. In Germany as in most of Northern Europe, solar is second to wind as a source of power generation.

Wind energy generation had a record year. This was due to favourable weather conditions and a slight increase in the number of wind turbines. At 138 terawatt hours, wind remained the largest source of electricity, producing more than all of Germany’s coal-fired power plants (132 terawatt hours).

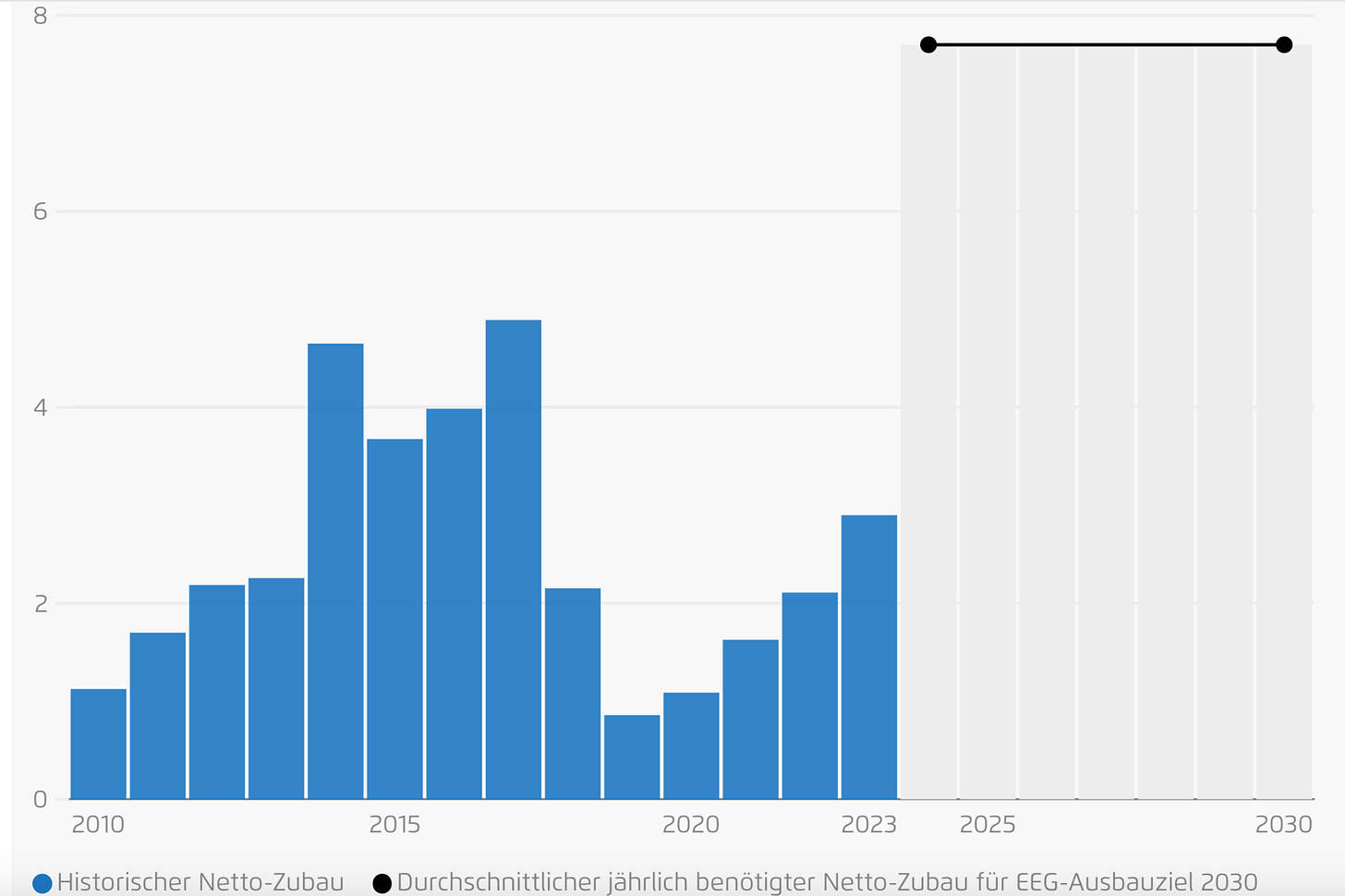

It would clearly make sense to double down on this success. But, unlike solar arrays which are relatively unobtrusive, wind expansion marks the landscape in dramatic ways and has become the object of considerable resistance across Germany. The result is that for all its proven success, the expansion of new wind capacity remains seriously disappointing. As Agora comments:

… the expansion of onshore wind power was much too low at 2.9 gigawatts. To achieve the country’s binding expansion targets for 2030, annual average wind capacity additions needs to rise to 7.7 gigawatts from 2024.

It is good news, that there has been a dramatic increase in wind projects approved relative to 2022 (74 percent). But the rate remains far too low.

The Wind Power Association (Bundesverband Windenergie) met with the government in two “wind summits” last year. These discussion exposed the striking fact that whereas in North and Eastern Germany permitting is proceeding quite smartly, in the Southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg there is a de facto stop. Though Bavaria and BW are two of the powerhouses of the German economy and though BW is governed by the Greens the two states account together for only 4.5 percent of new permit, meaning that BW authorized one wind farm and Bavaria 2. The new additions are coming overwhelmingly in Sachsen-Anhalt, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Schleswig-Holstein und Niedersachsen. If Robert Habeck’s embattled Ministry of the Economy and Climate is to meet its goal of quadrupling the rate of wind farm construction, it will have to break this blockade in the South. New legislation that came into effect in February 2023 that aims to streamline approval processes may help.

The decline in coal-fired electricity generation and the expansion of the renewable sector are good news. But if we break down the numbers, we see that the forces driving the 20 percent decline in overall emissions are more complicated and ambiguous than simply a switch from dirty coal to wind and solar.

The fall in power sector emissions was assisted, as Agora reports by a

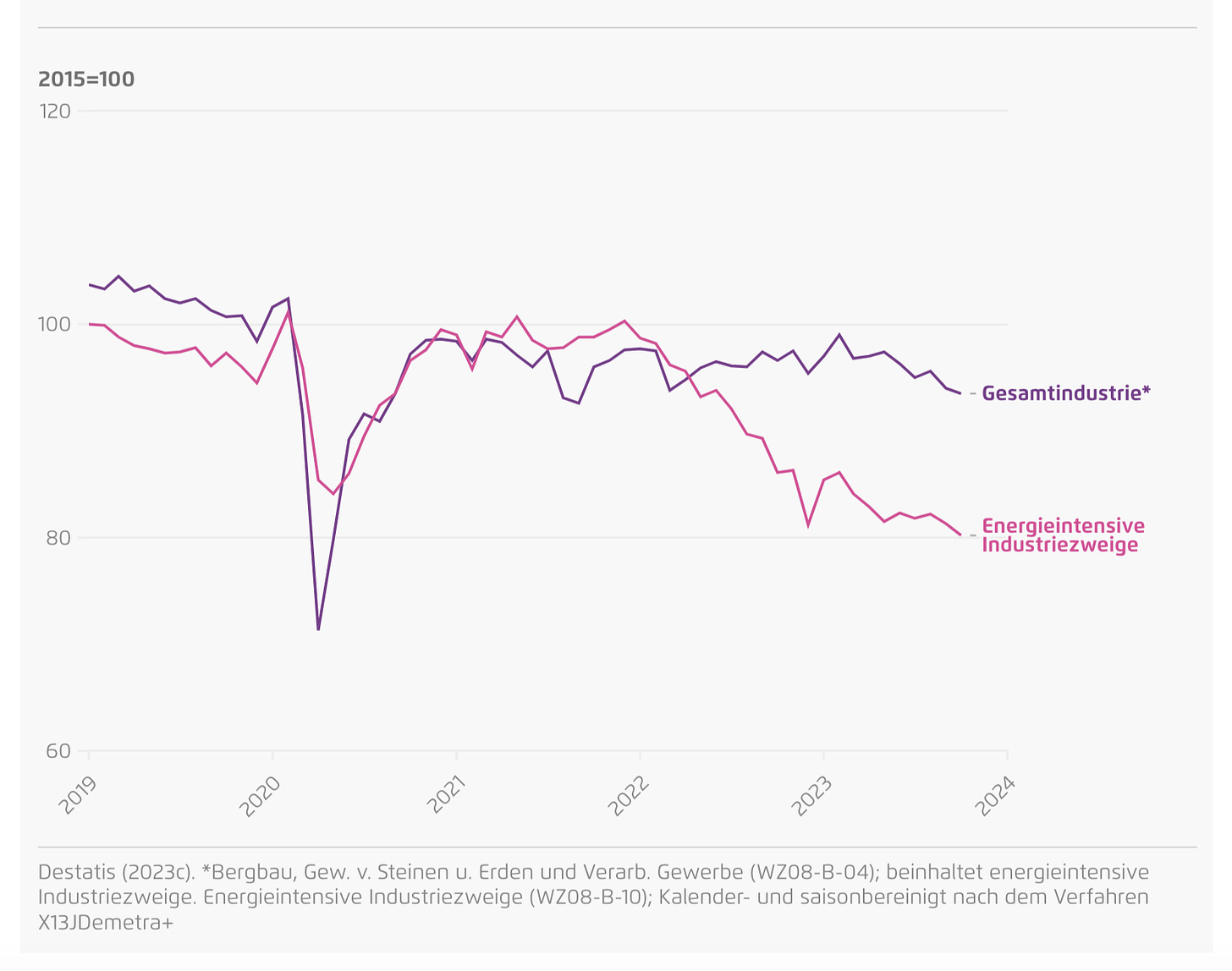

significant drop in electricity demand, increased electricity imports from neighbouring countries … as well as a commensurate decrease in electricity exports and a slight increase in domestic green electricity generation. Second, emissions from industry fell significantly. This was largely due to the decline in production by energy-intensive companies as a result of the economic situation and international crises. While overall economic output shrank by 0.3 percent according to preliminary figures, energy-intensive production fell by 11 percent in 2023.

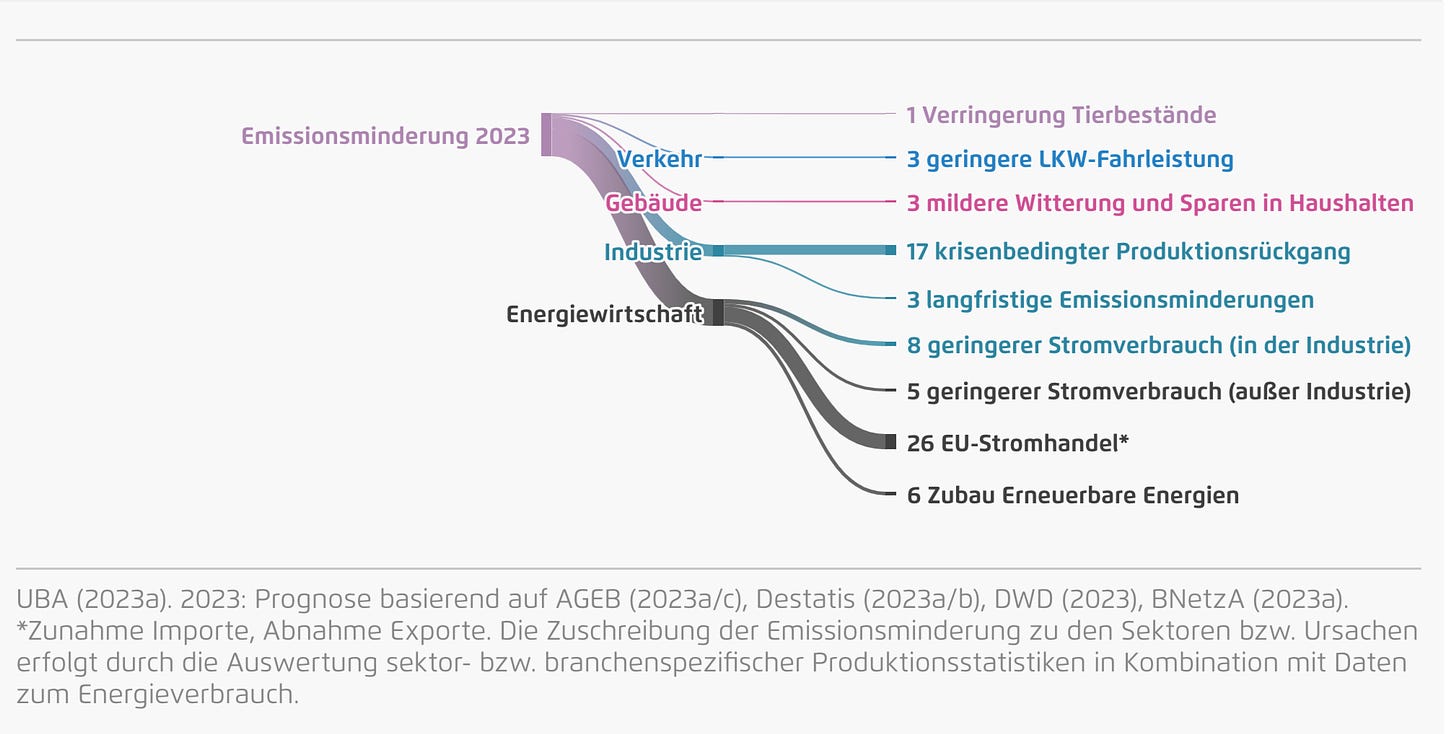

If we match sectoral data to underlying drivers we find the following:

Of the 73 m ton reduction in emissions in 2023 relative to 2022, we see that 26 m was due to net reliance on electricity imports from cleaner power sources - 49 percent of German electricity imports came from hydro and wind power - and 24 percent came from nuclear power. 17 m tons was accounted for by crisis-driven cuts to German industrial production. 8 m tons was accounted for by reduced power consumption in industry, 5 m tons by broader energy efficiency. Only 6 m tons of the total, less than 10 percent, was due to the expansion of renewables. 3 m tons was due to reduced use of heavy-goods vehicles (trucks), 3 m tons due to mild weather reducing household energy consumption, 3 m tons due to long-term reductions in emissions in industry and 1 m tons came from the reduced size of animal herds.

The bifurcation of German industrial fortunes has been striking. Whereas in the COVID shock, energy intensive sectors did rather better, since Putin’s attack on Ukraine and the energy price shock of 2022 the pattern has been reversed. Since 2022 there has been a 20 percent fall in energy-intensive production.

This is the backdrop to German anxieties about deindustrialization.

Despite the remarkable 20 percent cut in German emissions, Agora thus concludes on a worried note.

According to Agora’s calculations, only about 15 percent of the CO₂ saved constitutes permanent emissions reductions resulting from additional renewable energy capacity, efficiency gains and the switch to fuels that produce less CO₂ or other climate friendly alternatives. About half of the emissions cuts are due to short-term effects, such as lower electricity prices, according to the analysis. The think tank therefore notes that most of the emissions cuts in 2023 are not sustainable from an industrial or climate policy perspective - for example, if emissions rise again as the economy picks up or if a share of Germany’s industrial production is permanently moved abroad.

At least in power generation and industry there are clear signs of movement. The same cannot be said for two other major areas of emissions: buildings and transport. As Agora comments:

CO₂ emissions from buildings and transportation remained almost unchanged in 2023, resulting in these sectors missing their climate goals for the fourth and third successive time, respectively.

The coalition government turned the question of decarbonization in domestic heating into a political disaster. Legislation finally passed in September 2023 but not before it had been weaponized in the anti-Green culture wars. These have culminated in angry farmers attempting to storm a ferry carrying Minister Habeck back from his Christmas vacation spot, in protest at cuts to the subsidies they receive for vehicle and diesel fuel.

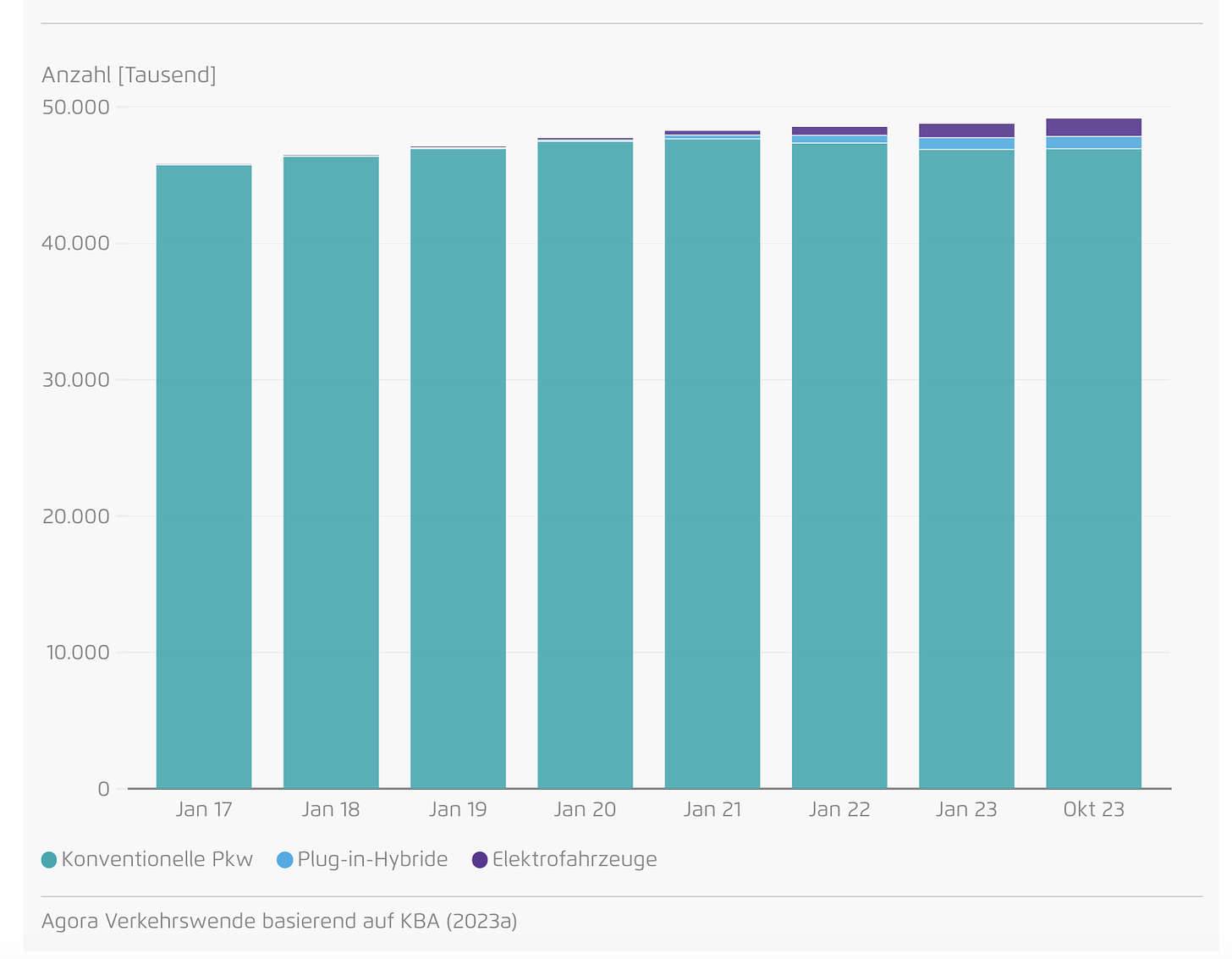

Meanwhile, EV remain a marginal presence on Germany’s roads, which are dominated by internal combustion engines.

As Agora comments:

By failing to reduce emissions in these two areas, Germany will likely miss its climate targets agreed under the European Union’s effort sharing regulation as early as 2024. The German government will have to compensate this failure to reach its goals by purchasing emissions certificates from other EU member states – or face fines.

And for the energy transition to progress seriously, it is not just on electricity generation and consumption that the government has to act. Crucially, it needs to dramatically expand the power transmission network, to enable it to distribute renewable power generation smoothly across the country.

According to official estimates by 2045 Germany needs to spend 310 billion Euros to almost double its transmission network from 37.000 to 71.000 kilometers. That would imply an annual construction of c. 1600 km. In fact, in the first half of 2023 only 127 km of new lines were brought into service. The good news is that new applications for permits in the first half of 2023 totaled 1950 Km up from 114 Km in the previous six month period. But the pace of acceleration that it now needed is dramatic.

Such an acceleration would require a broadly based coalition at all levels in society. And there is precious little evidence for that.

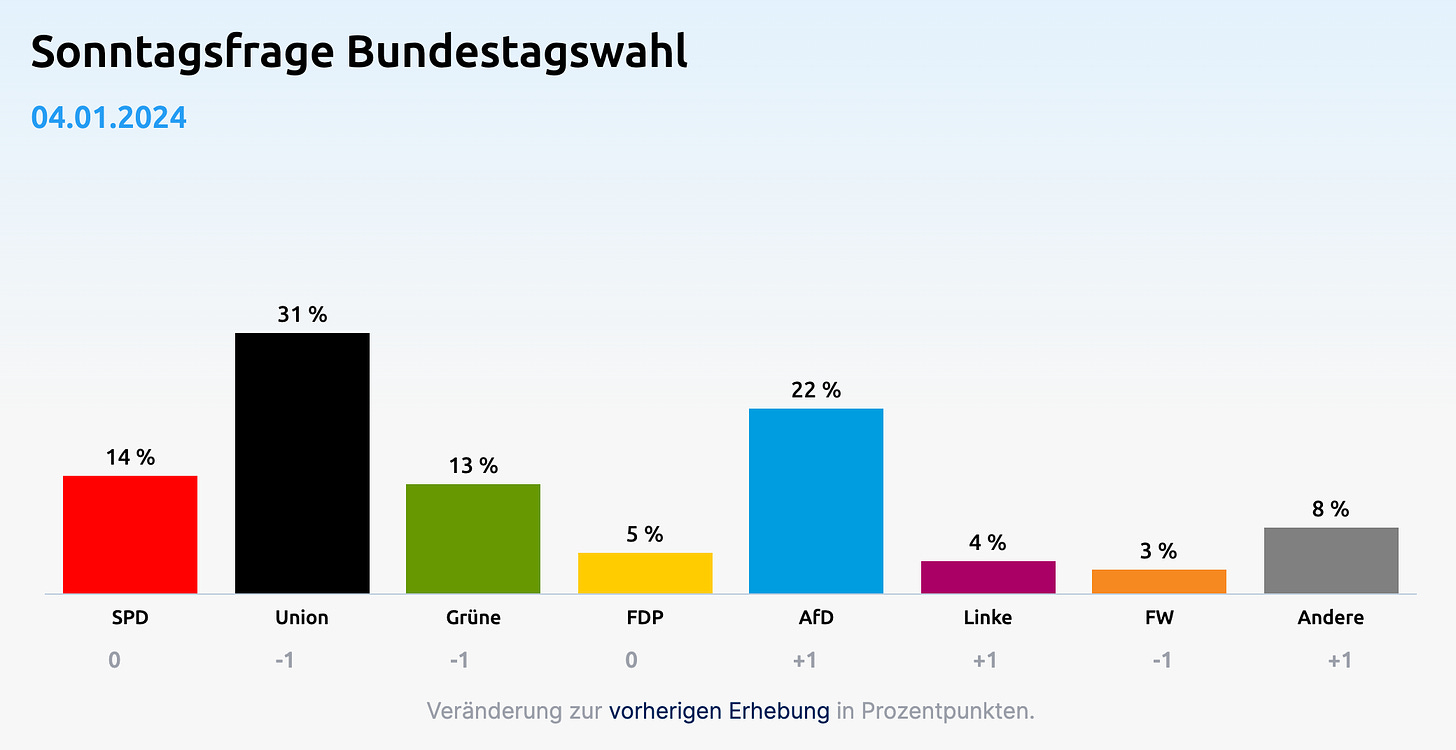

When Agora asked the German public what they thought the general level of support for greater climate action was, the number they arrived at was a sobering 31 percent. When one asks voters themselves whether they favor greater action the figure is slightly better, but only 43 percent.

Agora avoids making any comment on the current political situation in Germany. But the bitter reality is that Germany’s most climate-ambitious government to date currently enjoys the support of barely a third of the population, whereas the climate skeptical AfD is over 20 percent and the CDU/CSU, which under Friedrich Merz has taken a hard line on new taxes or public spending, sits at over 30 percent and will likely dominate the next government.

The good news is that elections are not due in Germany until October 2025 so the three-way coalition government still has time to gather itself. But unless it does, despite the remarkable CO2 emission figures for 2023, the political foundation of Germany’s energy transition will remain fragile. There is unlikely to be backsliding of the type that threatens the USA in 2024. Europe has a carbon pricing mechanism in place to which the CDU is at least notionally committed. Especially in power generation the commercial logic of the energy transition is powerful. But this is a far-cry from the kind of enthusiasm and ambition with which the traffic light coalition took office in 2021. It was animated by a sense that Germany needed large-scale generational reform and incongruous thought it might seem, the traffic-light coalition was the force to deliver it. Within the coalition the Greens were seen as the party that might break out to become a new Volkspartei, a new peoples party, uniting the reforming center. Whilst internal squabbling driven above all by the conservatism of the liberal FDP has helped to slow and at times paralyze the government, the Greens rather than emerging as a unifying political force, have found populist forces from across the political spectrum united against them. The bread and butter issues of the energy transition like the heating law, farm subsidies and fears about deindustrialization have not produced Gilt Jaunes-style mass protests, but are threatening to unify a powerful anti-Green bloc. The task of the next 18 months must be not only to hold the current government together, but also to find ways of splitting and fragmenting this coalition.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

Interesting and well written article. 'The devil is in the details', and this was a very good way to tell about it.

TL;DR the german political class would slit their own children's throats if an American will pay them on the head and call them good dogs.