Over an astonishing 20-year period between the mid 1790s and 1814, under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte, France came to exercise power over much of continental Europe. At its height, the Napoleonic empire extended the borders of France to the Low Countries, Italy and the Illyrian provinces. Meanwhile, Spain, Germany, Italy and Poland were formed into states under Napoleon’s control, often ruled by members of his family. Denmark, Prussia and Austria were forced to sign alliances on humiliating terms.

This rampage was the climax of the rise of French power that had shaped Europe since the 17th century. The conclusion of this arc, personified by Louis XIV and materialized in his monstrous palace at Versailles, was all the more dramatic for the fact that in 1792 the French overthrew their monarchy and in 1793 they executed their king.

Bonaparte was a conquering Republican general who made himself emperor, a model that Europe had last seen on this scale in the age of Rome. And Napoleon was not just any conquering general. On land the French armies under Napoleon’s command swept everything before them. This was itself historically novel.

Military commanders have always dreamt of glory. At least since the 17th century and the times of Gustavus Adolphus, European generals had sketched ambitious plans of campaign and visions of conquest. But warfare in the 17th- and 18th-centuries was more often than not a slow and indecisive slog. In the 1740s and 1750s Frederick II of Prussia fought several memorable battles that earned him the title “the Great”, but he was fighting on the defensive for most of his illustrious career and the scale of Prussia’s armies was modest. A major engagement in the Seven-Years War involved less than fifty thousand troops on each side.

Napoleon’s Grand Armée was ten times that size. He deployed its corps and divisions on a continental scale. Between 1805 and 1807 Napoleon’s encirclement maneuvers delivered devastating defeats to Austria, Russia and Prussia. The climactic battles of the Napoleonic era were fought by hundreds of thousands of troops. Military history took on a new scale.

As never before, campaigns, concluded by decisive battles redrew the map of Europe. After Austria’s devastating defeats in 1805 at Ulm and Austerlitz, the venerable one-thousand year old Holy Roman Empire abolished itself. Napoleon gave the sprawling territory of German-speaking Europe a new political form. Dukes were promoted to kings. The upstart Prussian state, which Frederick the Great had raised to fame, only survived its catastrophic defeat of 1806-7 thanks to the good graces of the Tsar.

If the period between 1790s and the early 1800s was, according to Reinhart Koselleck, the period in which the modern Western conception of secular history took shape (Sattelzeit), then Napoleon was perhaps its first hero (or anti-hero). If there was such a thing as history, then Napoleon showed how war and military command could make and remake it.

Not for nothing, Hegel described the emperor cantering through Jena as the “world soul” on horseback. It was the historical efficacy of Napoleonic war-fighting that Prussian theorist of war, Clausewitz, tried to grasp with his radically historical and romantic view of war as an antidote to the rationalist and geometric conceptions of war beloved of the 18th century.

One hundred and eighty years later, the historian, Thomas Nipperdey began his history of 19th century Germany with the simple statement: “In the beginning was Napoleon”.

***

These thoughts were provoked by Ridley Scott’s execrable film about Napoleon, which Cameon Abadi and I discussed on the Ones and Tooze pocast this week. In addition we addressed a variety of other questions including:

How did he finance his wars?

And should he be remembered as a progressive or a conservative?

Those are a few of the questions that came up in my conversation with Cameron Abadi on our FP podcast Ones and Tooze. You can listen and read more here.

If Napoleonic warfare made history on a scale not before seen in Europe, he could not, in a short period of rule upend the socio-economic conditions of power in the same way.

Napoleonic war was on a larger scale and with much more sophistication organization than previous war-fighting in Europe. The battlefield casualties were worse than ever, given the huge number of troops engaged. Protracted guerilla war, as in Spain, devastated civilian life and disrupted the economy, as well. According to one recent estimate by Leandro Prados de la Escosura and Carlos Santiago-Caballero, excess mortality in Spain during the period of the Napoleonic wars came to perhaps 1 million of which one third were direct military casualties. Spain’s population at the time was around 14 million. This is horrible and in keeping with Goya’s famous images of the horrors of war, but also far short of the 20-30 percent death rates seen in early modern conflicts, where famine and disease interacted over years with protracted pillaging.

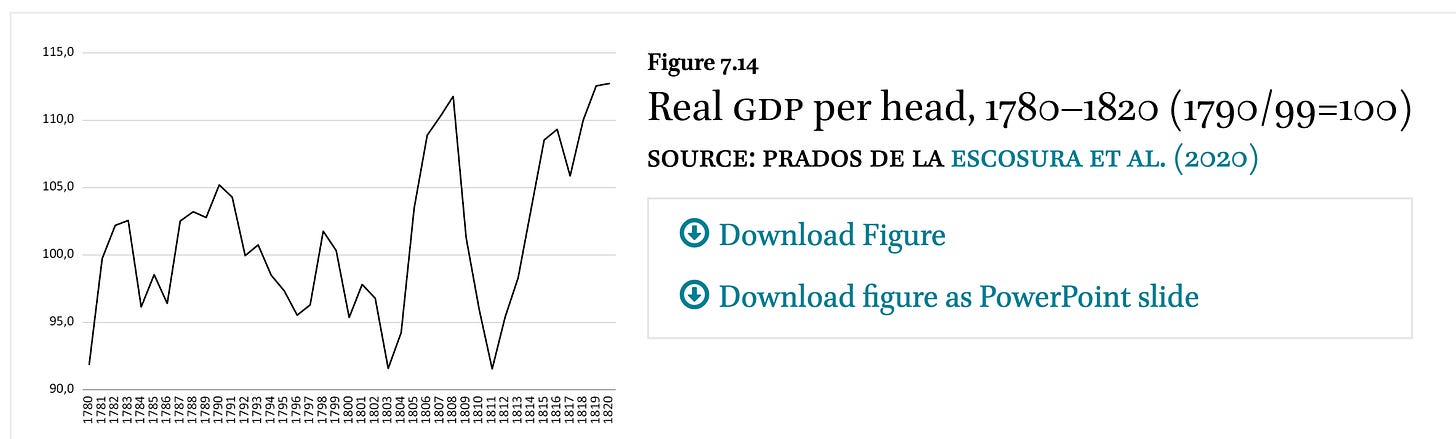

The Napoleonic wars did not, even in Spain, produce the implosion of ordinary life witnessed in parts of central Europe during the Thirty Years War of the 17th century. Our best estimates of GDP per capita for Spain show large swings but a very rapid recovery at the end of the war, which would not have been possible in the case of devastation.

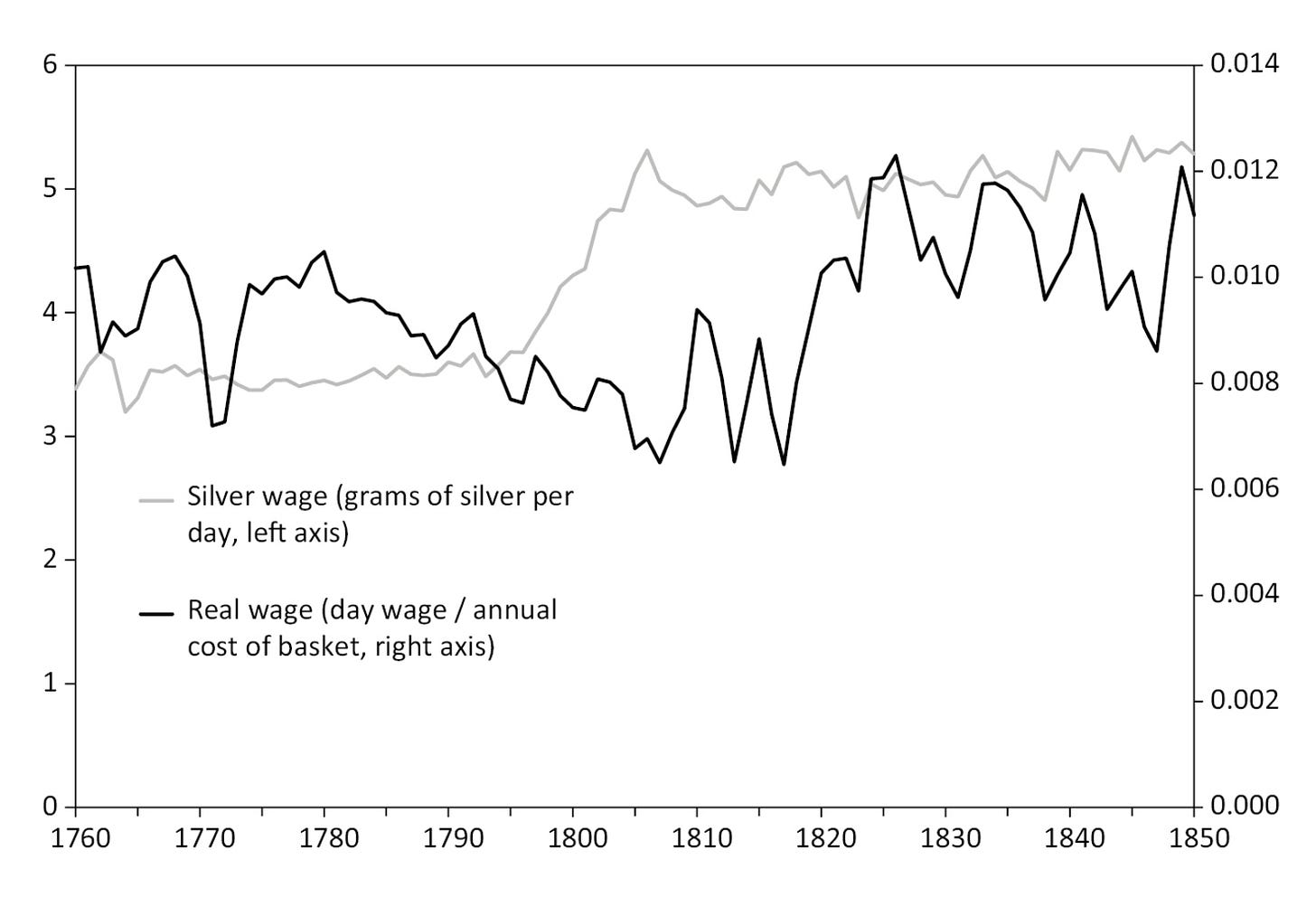

In Germany too Ulrich Pfister’s data show real wages reaching a nadir during the early 1800s but the decline had started long before the shock of Napoleonic invasion.

In France itself Napoleon’s financial reforms put an end to the revolutionary inflation of the 1790s. The Banque de France was set up in 1800 and in 1803 issuance of the Franc Germinal began, securing a platform for French war finance, which relied on a healthy balance of reparations and exactions, taxation and new borrowing. The latter was made easier by the fact that the 1790s had seen the huge debts of the ancien regime written off.

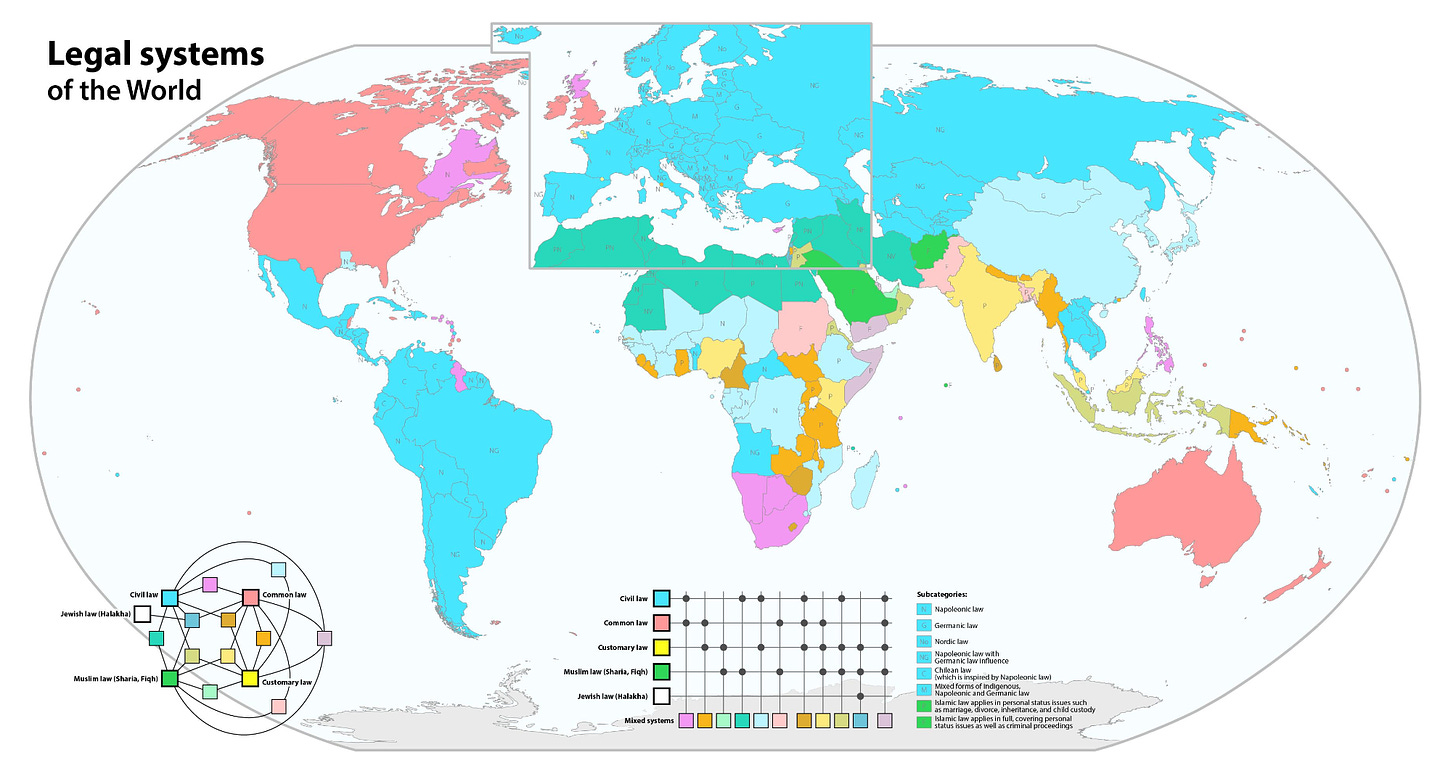

The most enduring legal reform of the Napoleonic period was no doubt the Napoleonic legal code, which became formative for legal systems throughout the world.

But Its impact was felt more in the long-run than in immediate changes to the French economy.

Napoleon would no doubt have liked to engage in large scale infrastructure construction, on roads and canals. But the demands of the war crimped his ambitions. De facto according to modern estimates, France’s road infrastructure likely deteriorated over the course of the revolutionary and Napoleonic periods.

Napoleon’s most dramatic economic policy was no doubt the continental system announced after the French occupation of Berlin in November 1806. This was a radical effort to strike at Great Britain by excluding its goods from European markets. Britain responded with a blockade and worldwide war-making against the France Empire.

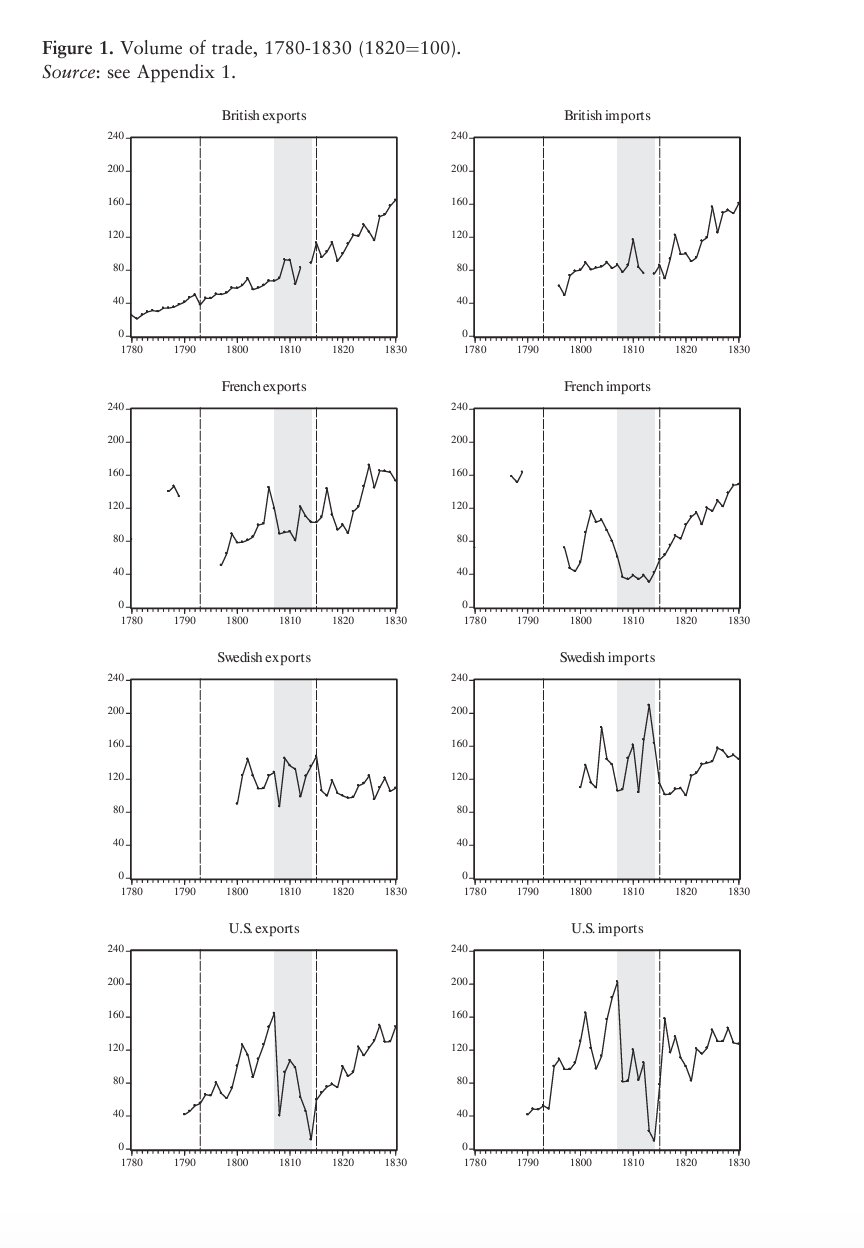

The impact on the economies of France, Britain and the wider world economy is clearly visible even in the scanty economic data of the period. As Kevin O’Rourke has shown, trade flows fell. French trade was hard hit by the defeat of its efforts to recapture Haiti, its preeminent sugar colony.

Prices around the world were wrenched out of shape.

Deprived of imports, the United States began to develop a cotton textiles industry. Meanwhile, the old imperial trading companies like the East India Company lost many of their privileges. Once the war was over, trade with Asia would be much freer.

The broader point is that as magnetic as the figure of Napoleon may be, in focusing narrowly on the Emperor’s plans and ambitions, we underestimate the impact of the “Napoleonic era”, which was defined both by French action and the massive counter-acting forces that were mobilized against him.

Napoleon’s excessive ambition and success summoned up peripheral coalitions that after his defeat would dominate European affairs for much of the early 19th century. In the East, Russia emerged as the arbiter of continental power. The Tsar’s cossacks cantered through the streets of Paris in 1814. Russia would have a decisive voice in German affairs until Bismarck spied a window of opportunity to resolve the German question in the 1860s.

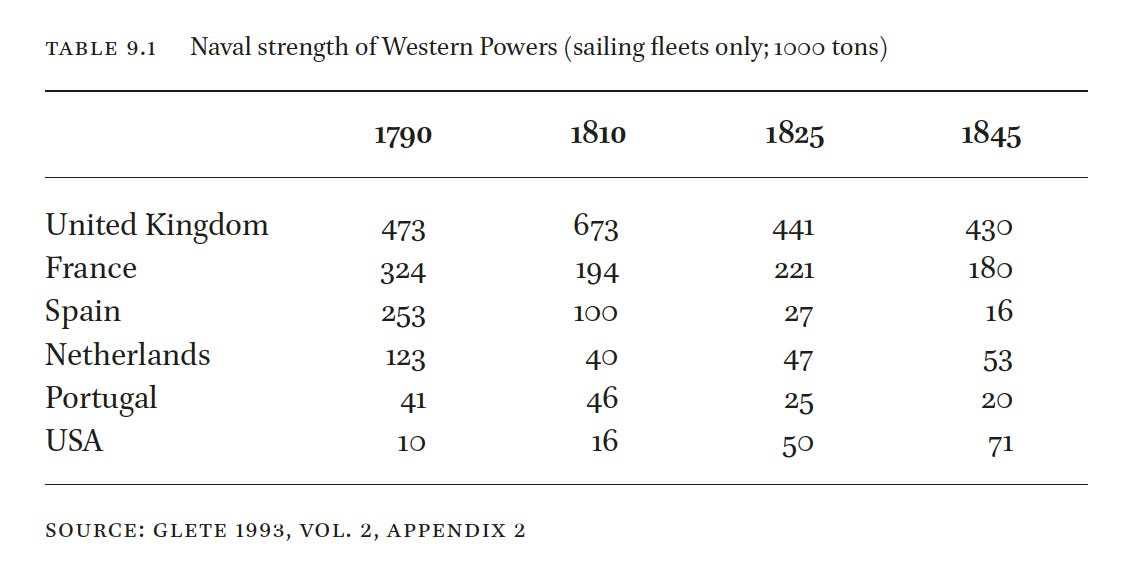

Offshore, the British Empire held Napoleon in check. Napoleon’s great victories in Germany in 1805-1807 followed on the decisive defeat of the French and Spanish navies at Trafalgar.

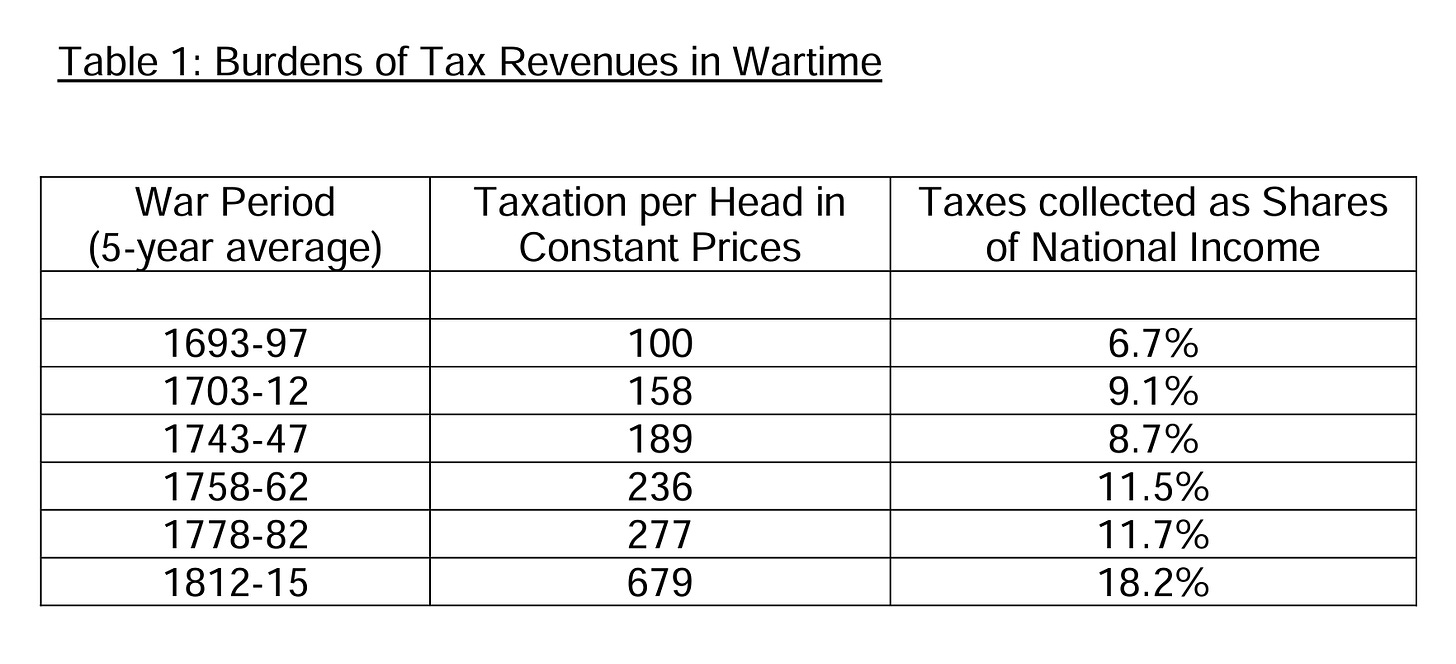

To fight Napoleon and bankroll his enemies, London mobilized an unprecedented financial war effort that may have extracted as much as 18 percent of GDP in tax, an astonishing figure for a country on a GDP per capita as modest as that of the UK in the early 1800s. At a rough estimate, the UK in 1800 had a GDP per capita of roughly $2500 in modern dollars. To devote 20 percent of that to a foreign war, was a huge mobilization.

Source: Patrick Karl O’Brien (2011)

And onerous as they were, Britain’s debts did not leave it bankrupt. With the gold standard restored by the 1820s, and conservative austerity imposed, London emerged from the long struggle against revolutionary France as the financial capital of the world.

Britain also commanded the highways of the oceans more than ever before. It was the Napoleonic wars that laid the foundations of UK naval supremacy.

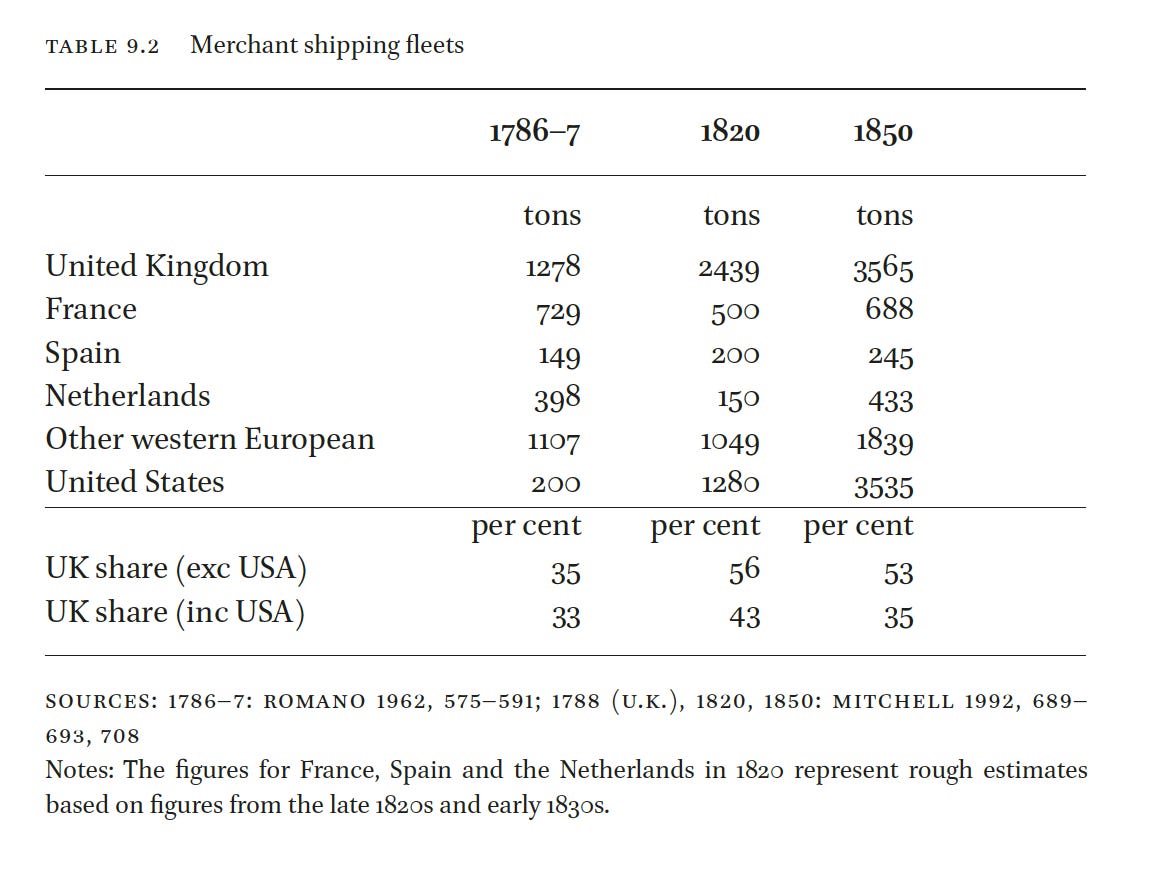

Britain also consolidation its advantage in merchant shipping, where its share of European shipping capacity surged from one third to more than half.

By the 1820s the outlines of a new global economy were visible, a new “global condition” that was framed by the Britain’s global empire (Geyer and Bright World History in a Global Age). Of course it is possible that London might have mobilized the resources necessary to establish this dominion without the French challenge. But it seems unlikely that the fiscal effort would have been so large and it is in any case speculative. History as we know it was shaped by the climactic struggle between Napoleonic France, Britain and Russia. And so, not just for Germany, but for wider world history, we must take seriously the simple but also bind-bending injunction that: “In the beginning was Napoleon”.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:.

Napoleon’s legacy, as dissected by Adam Tooze, is a testament to the power of historical forces in shaping our present. The strategic and political acumen of Bonaparte, as narrated in ‘Chartbook 251,’ mirrors the complexities of leadership and influence that continue to resonate in today’s geopolitical landscape. Tooze’s article not only revisits the grandeur of Napoleonic campaigns but also challenges us to reflect on the narratives that define progress and authority. A truly enlightening read that bridges the past with contemporary discourse.

Having sat through this $200,000,000 stinkaroo, I have to agree with Adam and the entire French nation. What a pile of merde!

I can almost live with rampant ahistorical plots, but the payoff has to be entertaining. This film isn’t.

The economics of the era are usually absent from histories as they concentrate on the wars and Napoleon’s massive ego. I appreciated Adam’s insight as always.