Did Putin’s war on Ukraine and the ensuing energy crisis lead to a retreat from the energy transition in Europe? Did Russian aggression expose the vanity of green ideology? Was a war what we needed to relearn the “basic math” that modern societies cannot do without some combination of fossil fuels and nuclear? This was the contention of pieces in Foreign Policy over the last 12 months notably by Brenda Shaffer and Ted Nordhaus. Since I share the pages with these authors I decided to write a rebuttal.

As the evidence clearly shows, the idea that Europe was falling back in love with fossil fuels is, in fact, very wide of the mark.

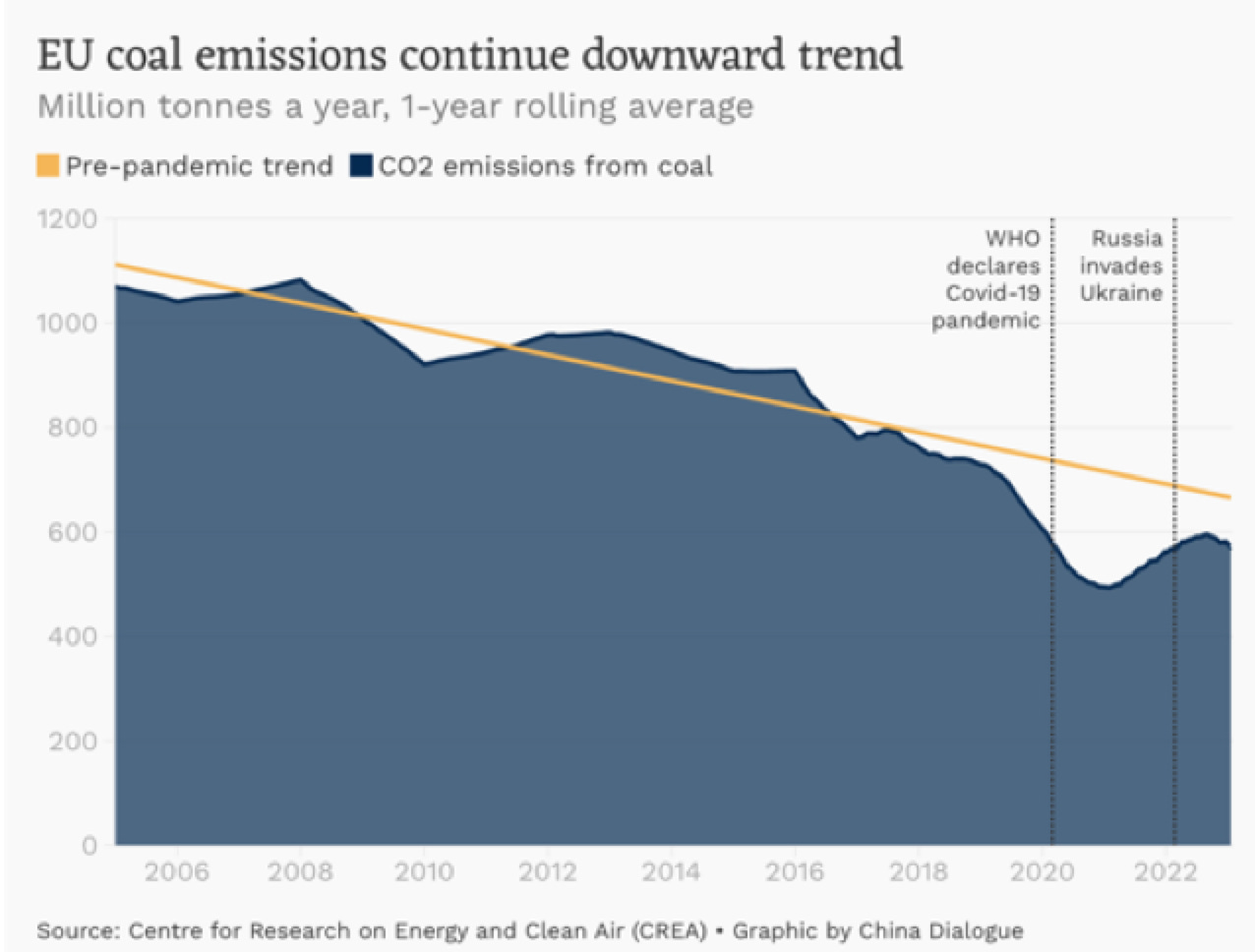

Though some coal-fired power stations were reopened and Europe imported more coal, these were precautionary measures. Though coal consumption blipped up for a few months it did not break the downward trend of recent years.

Source: Lauri Myllyvirta

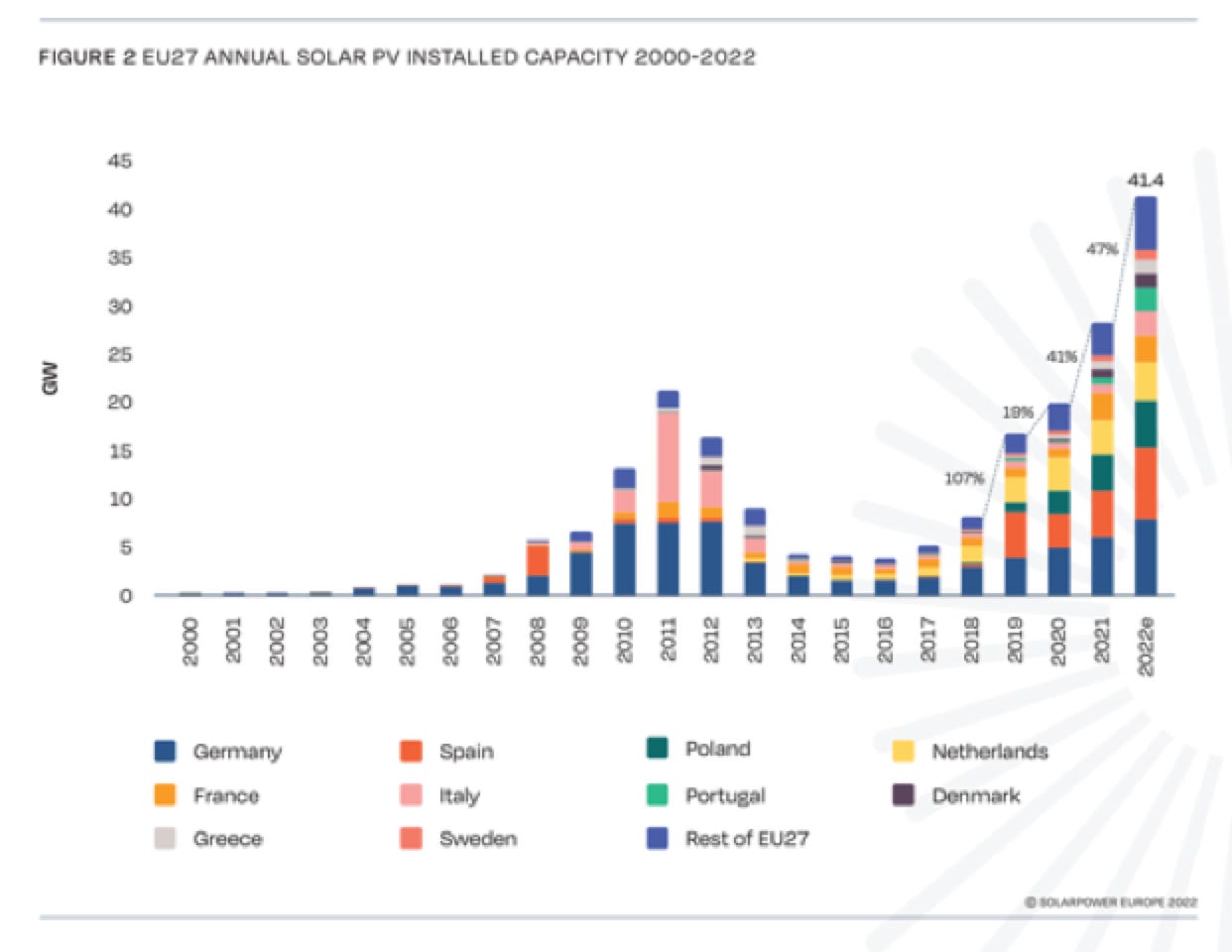

Renewable investment surged to record levels. In solar Europe is now installing twice its previous record set a decade ago.

Rather than offering a dose of clear-thinking and realism what the critics of European energy policy in the pages of Foreign Policy reveal are their own political preferences, which revolve around a critique of a certain kind of environmentalism and a commitment both to fossil fuels and atomic power. That is fair enough. In commentary all of us blend opinion, judgement and fact. But one has to ask what purpose and whose interests are served by this kind of critique. To me it smacks of the fossil-fuel scare-mongering and rear-guardism that we saw around the “greenflation”-scare of 2021 - what I then dubbed a “climate kalecki” moment.

Independently of the position they advocate, it is worth noting whether a commentator is able to make their political worldview engage with substantial trends in reality, rather than “will of the wisps”, like the supposed return to coal. And regardless of its empirical grip a line of commentary really demands our attention if it has influence in the domain of policy in the broadest sense, whether in the public or private sector.

In this regard a more interesting take on Europe from the American sides comes from the axis that runs from the folks in the White House who drafted the March 10 communique of the von der Leyen - Biden meeting, by way of Todd Tucker, impresario of industrial policy at the Roosevelt Institute, to Yakov Feygin of Berggruen Institute and the Building a Ruin newsletter. These observers also operate in the register of realism, but theirs is a more sophisticated take on European-American relations, both with regard to energy policy and history.

Feygin has been writing in a very interesting vein about the American developmental state. Most recently he penned a blistering account of his generation’s disillusionment with the “good Europe”. Writing about a recent trans-Atlantic meeting, Feygin observes:

Quite bluntly, between the IRA bashing that is really an avatar for internal squabbles, never once did (his European interlocutors register, AT) … that the EU has a serious image problem in the United States. And that image problem is not with the traditional Republican opponents of the EU but with a newly energized left-liberal arm of the Democratic Party that sees the EU as a neoliberal obstacle to radical action and a dinosaur that still believes history is over.

Like it or not, I recommend it as reading to anyone on the European side wanting to get a sense of the range of American opinion right now.

Moving to the very heart of the industrial policy crowd in Washington right now, Todd Tucker’s twitter feed offers a rich running commentary both on the technical aspects, the politics and atmosphere of trans-Atlantic climate and industrial diplomacy. Tucker writes from an engaged and unapologetically national point of view, but with a view to communicating clearly with Europe about differences and finding ways to square the circle. He is interested in constructive influence in Europe, with an important recent essay on trade policy being translated into French and Spanish by way of Grand Continent the highly influential Paris-based geopolitical think tank (in English here).

Tucker in turn is close to the folks in the White House who have been working for months to make the best of the global kerfuffle unleashed by America’s chip wars and the Inflation Reduction Act. Though (or perhaps because) the Inflation Reduction Act was not crafted by the administration, but was made in Congress, it has stirred up relations with Korea, Japan and Europe. The Biden team have been working overtime to turn that to the advantage of American grand strategy. The fruits of those diplomatic labors include in the last moth, the deal with Japan on strategic materials and the joint statement issued from the von der Leyen-Biden meeting of March 10th. Its key points include

•EU-US to begin negotiations on a targeted critical minerals agreement, also possibly a work around on IRA.

•Clean Energy Incentives Dialogue to coordinate respective incentive programs so that they are mutually reinforcing i.e. “do our best to avoid further nastiness over IRA and CBAM”.

•The Clean Energy Incentives Dialogue will become a part of the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council where it will also facilitate information-sharing on non-market policies and practices of third parties i.e. China.

•Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum first touted at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021 to be concluded by October 2023, before the current trade truce expires, also targeted at China.

•G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), an idea first launched back in 2021 that is now to be given some juice - counter to China’s BRI.

•Agenda to evolve the multilateral development banks, starting with the World Bank with the change of leadership pending and climate and debt relief high on the agenda - ditto with regard to BRI.

Signed off on by the European Commission, this memo figures Europe and the US as loyal partners in a cooperative move towards energy transition with the clear purpose of confronting, competing and containing Chinese influence. The document offers an admirably clear and comprehensive sketch of how Europe fits into the Biden administration’s strategy with regard to industrial policy (foreign policy for the middle class i.e. jobs for working class Americans), climate and China.

Questions of realism arise here with regard to America’s own commitment to such a vision. Can the world’s largest fossil fuel producer really be a credible partner in the energy transition? And also with the willingness of either Europe or the USA to go to the necessary scale on global development. Over five years the PGII aims to mobilize $600 billion, of which $200 billion is America. This, as everyone involved must realize, is a tiny fraction of what emerging markets and low-income countries need in terms of investment. Estimates presented to COP27 suggested the need for an additional $1 trillion per annum for low income and emerging market investment. In light of this huge gap, one has to ask whether the US-EU vision is a serious answer either to China or the the urgencies of the moment, or just another pleasant-sounding but ultimately ineffectual squib, of which the new era of “development finance” has already produced so many.

Finally there is the question of where Europe actually stands. The question posed in more or less subtle and telling ways by all the American commentators. Von der Leyen’s diplomacy in Washington in March, met with far from universal applause in Europe. In Paris recently I heard notably skeptical tones. Pascal Lamy a close confidant of Macron is arguing for a more aggressive stance against the United States. As Lamy puts it:

The second option is to rebuild with several countries a North–South coalition promoting open trade while respecting various collective preferences, the most common of which is now environmental protection. Such a coalition would start from what already exists, but without the Americans, hoping to create a disadvantage for them that would make them change their position. This is the strategy that I would prefer.

Certainly Macron’s visit to China suggests that Paris does not want to be corralled. Chancellor Scholz made the same thing clear on his visit to Beijing. And the commission’s target for self-sufficiency in the recently launched Net Zero Industry Act is 40 percent, a long way short of the made in America line laid out by the IRA.

Meanwhile, for all huffing and puffing about the Inflation Reduction Act, there is on the European side a deep sense of political paralysis, which I address in an FT op-ed today. Getting to the Inflation Reduction Act may have been a nightmarish process for all involved in Washington, but at least it was a political bargain within the Democratic Party majority. Europe right now is shrinking from any major political debate. France and Germany both have domestic “issues” and their bilateral relations are fraught, notably on the energy issues, particularly around nuclear. Neither Paris nor Berlin seem to have the stomach for the kind of grand bargain that in 2020 turned the COVID crisis into the great leap forward of NexGenEu. And yet Europe needs to summon the political energy, because though it is silly to suggest that it is retreating to coal and abandoning the energy transition it is also clear, that, like the United States, it is still not moving fast or comprehensively enough.

***

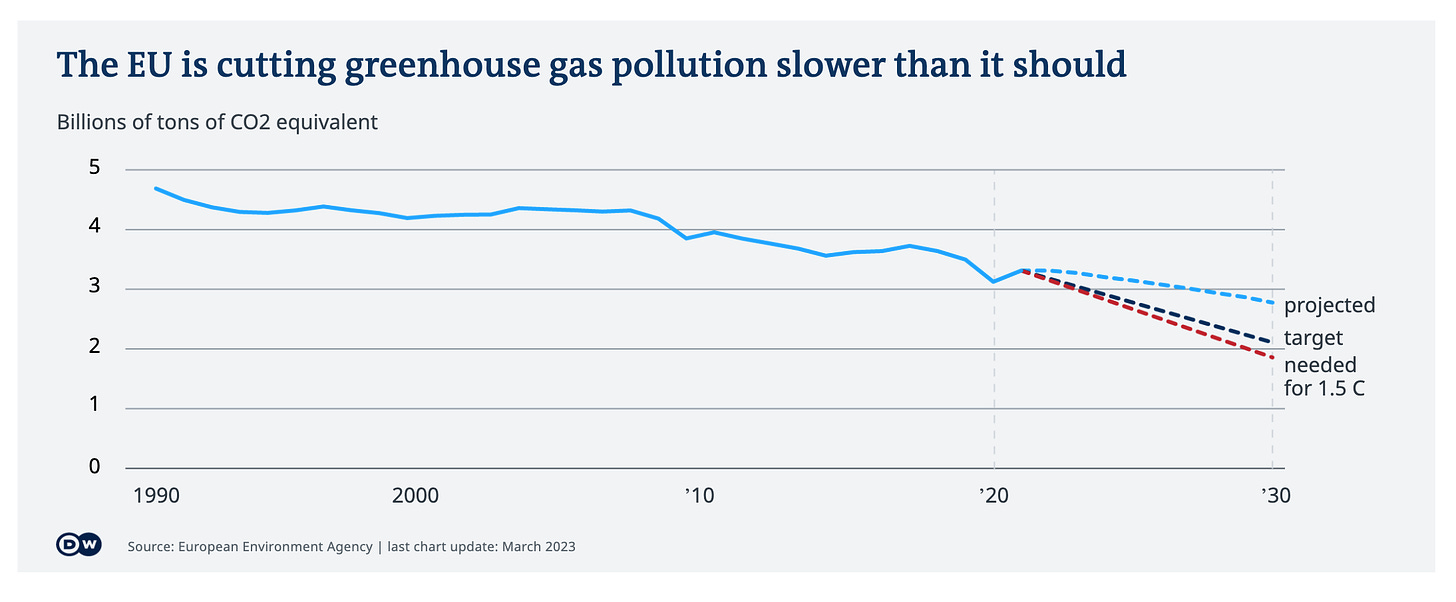

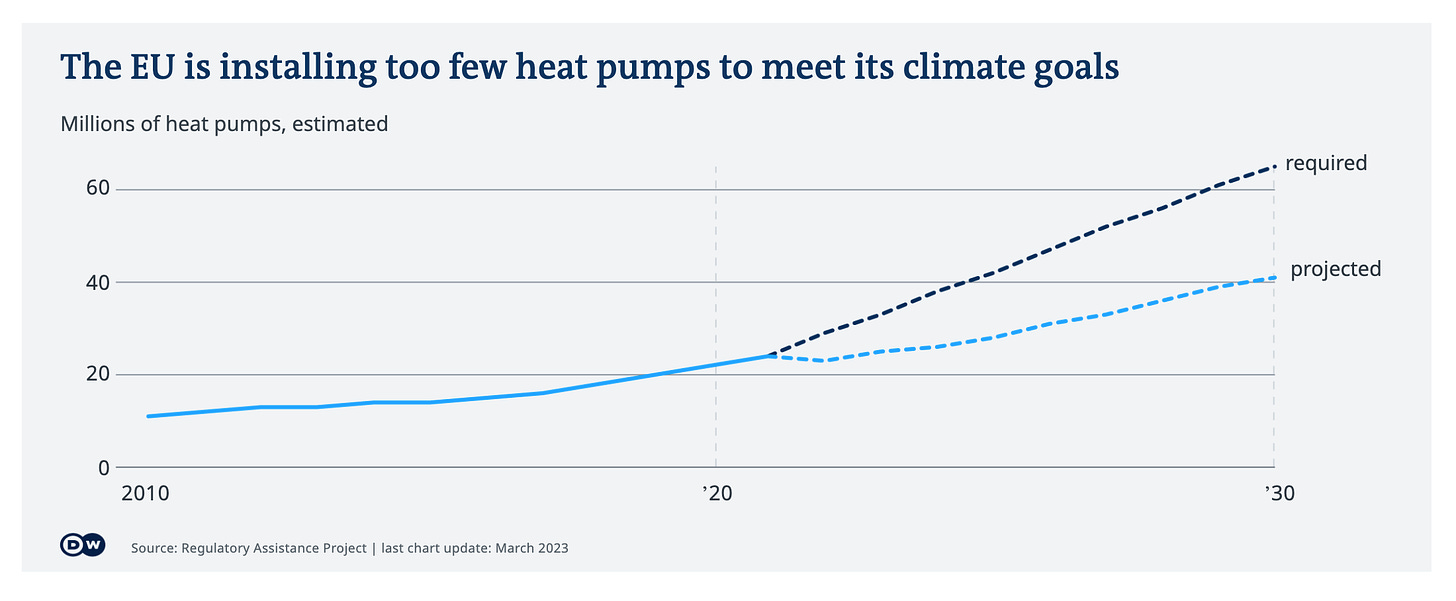

To see what I mean check out the handy benchmarking exercise being run by Deutsche Welle and European Data Journalism Network.

In the wake of the COVID-rebound, Europe is on track to continue cutting its emissions, but it is currently falling far short of its 2030 targets.

On power generation it is now ahead of the curve on solar, but still lagging behind the projected targets for wind power-generation. But even more serious is the deficit when it comes to domestic heating. On heat pumps it is currently on track to fall 50 percent short by 2030.

EV now make up 18 percent of new cars registered in the EU. A German effort to derail the phasing out of new internal combustion engined cars has been contained. But the share of EV needs to leap in coming years, which will require a huge investment in charging and green power supply.

On agriculture, the fifth key element of the energy transition - along with power, industry, transport and buildings - Europe has made next to no progress.

****

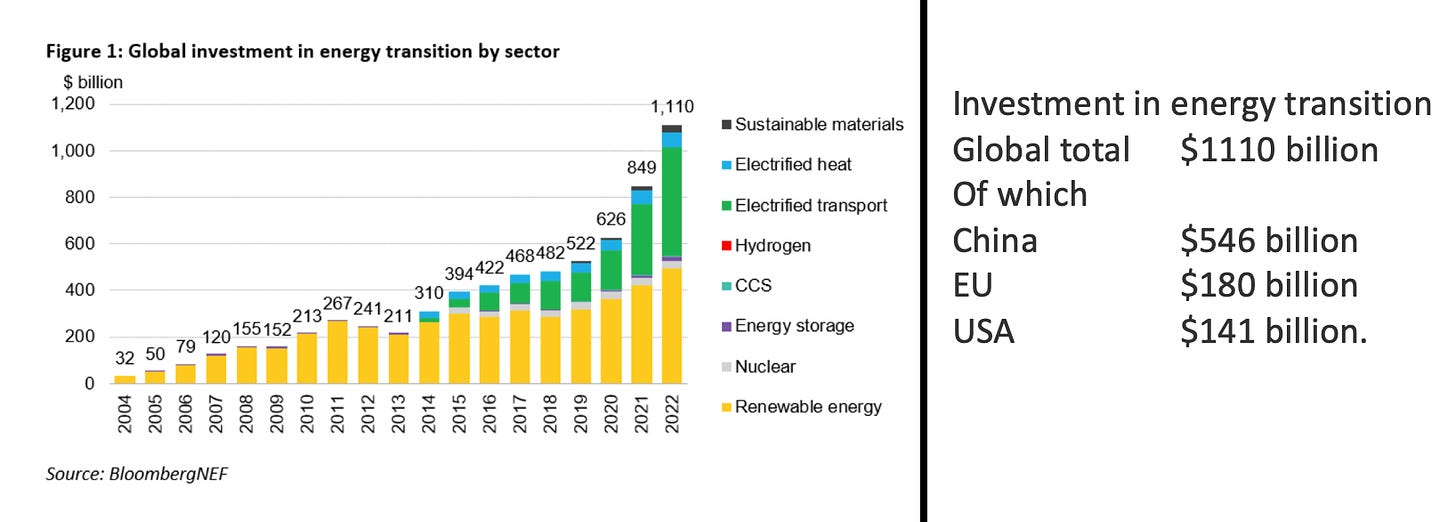

The acceleration in 2022 was real and significant, but it is not enough. What would a truly large-scale investment push look like? Look no further than the more or less hidden referent of the entire European-American discussion, China.

To put the following in perspective let us start with the generally agreed fact that China’s GDP in current dollar terms is roughly the same size as that of the EU and considerably smaller than that of the US. In per capita terms it is much lower than either of its Western competitors. And yet, according to data compiled by BloombergNEF, China’s investment in the energy transition in 2022 was 70 percent greater than that of the US and the EU combined.

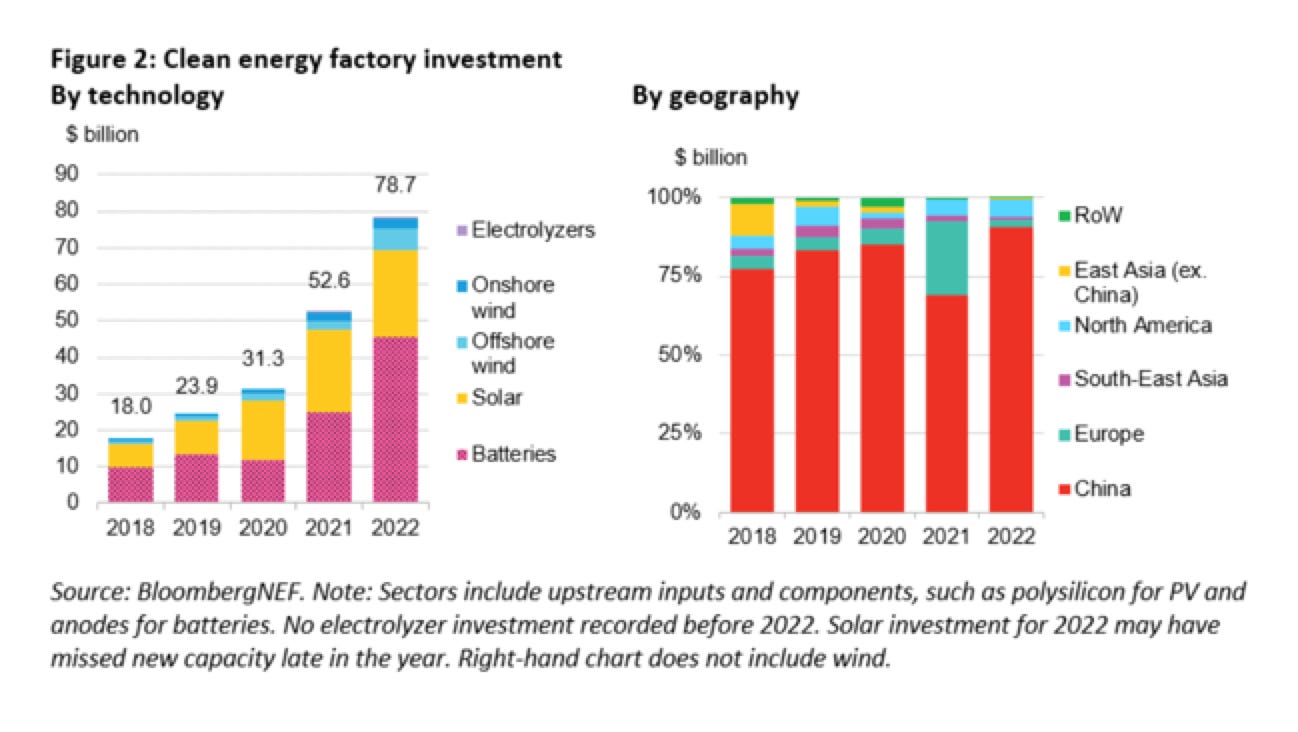

China’s dominance in upstream investment - in the facilities that produce batteries, PV and EV - was even more dramatic. In 2022, China accounted for 90 percent of investment in the factories that will make the equipment and components necessary for the energy transition worldwide. In the last five years, China’s share in this upstream investment has only once dipped below 75 percent.

Now there may be quibbles with both the Bloomberg data and the GDP numbers. And the full effects of Europe’s programs and the IRA are yet to make themselves felt. But even the largest estimates of the IRA’s cumulative impact over ten years - $1.2 trillion in public support plus $3 trillion private - on top of what the United States is already spending, will do no more than match China’s current effort, on a much smaller gdp per capita. And, all analysts agree, that if China is to meet its decarbonization objectives - the current trend in its emissions is a matter of some dispute - it spending will have to ramp up considerably.

In short, we are all having a problem of realism.

***

The energy transition is gathering momentum in the US and Europe. It is driven at this point by hard technological facts, security concerns and commercial calculation, as much as vision or ideology (which btw are normal parts of any investment decision). Putin’s war is, if anything, accelerating the shift. Carping from both sides should not distract us from these realities.

But neither \should the narcissism of small differences in the West blind us to the bigger picture. There is a huge gap between China, Europe and the US in terms of the current pace of investment. The difference in upstream investment means that for all the announcements triggered by the IRA, 2022 was a year in which that gap between China and the West widened, rather than closing. The idea of a Western green alliance remains on paper and untested under serious strain. Its impact on the overall pace of the energy transition is uncertain and will depend amongst other things on China’s reaction. If they end the export of PV manufacturing equipment, for example, it could have a disastrous impact on the pace of investment in the West. And, on all sides, there is a gulf between rhetoric and the emissions reductions, which as far as climate stabilization is concerned, are the only things that count.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you wil receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

One of the best Tooze commentaries. Yes, authoritarian regimes can maneuver policy more quickly and powerfully than democracies, for better or worse. Even when employed for the good, China's resource allocations are behind the curve in a most worrisome fashion, and the rest of us are mostly sidelined by our preoccupation with present concerns and political stalemates. We did not evolve to be concerned with survival of the species, rather the reproduction of ourselves. Sublimation of those drives has its limits, and we are constantly coming up against them...

To put the following in perspective let us start with the generally agreed fact that China’s GDP in current dollar terms is roughly the same size as that of the EU and considerably smaller than that of the US.

How meaningful is China's GDP in dollar terms? Are the solar panels and windmills installed in China bought and paid in dollars? With de-dollarization of critical energy and materials supply chains, soon enough not even the energy (almost exclusively from fossil fuels) or materials (extracted using energy from fossil fuels) that go into them will be paid by USD. Looking at PPP, Chinese economy is already quite bigger than US:

https://www.worldeconomics.com/Indicator-Data/Economic-Size/Revaluation-of-GDP.aspx

Solid analysis based on PPP premises also explains why Russia's economy is not anywhere near the much predicted collapse:

https://simplicius76.substack.com/p/the-truth-about-russias-economic