US grocery mayhem, the weight-loss boom, the history of meat extract and anti-humanism.

Great links, images, and reading from Chartbook Newsletter by Adam Tooze

Thank you for opening your Chartbook email.

Phantom in the rearview, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, sand, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, water from the Pacific Ocean and acrylic sheet on White Oak on Yellow Pine. 48 × 48 in / 121.9 × 121.9 cm. Source: Interview Magazine

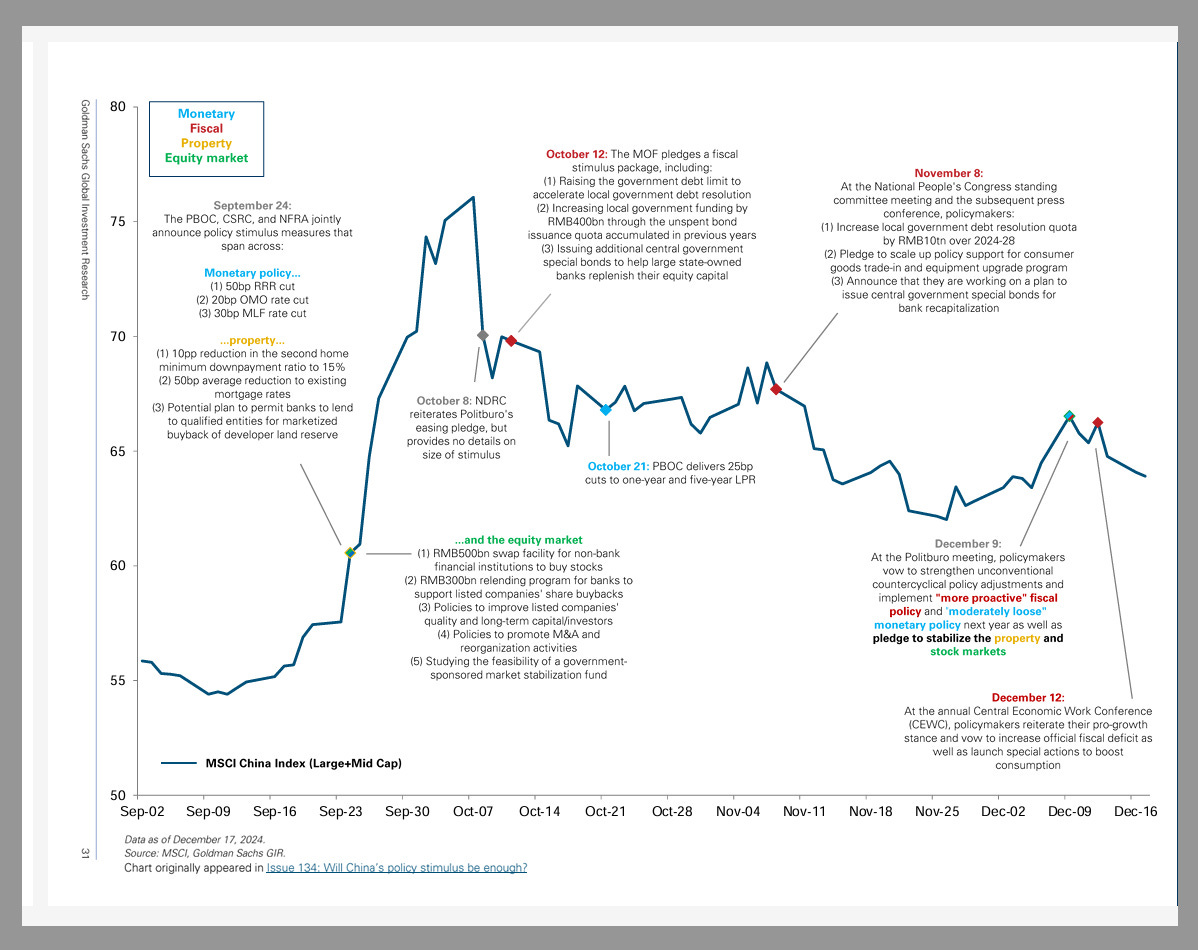

China’s stock markets continue to look for stimulus help

Source: Goldman Sachs

Grocery Mayhem in the USA

When America’s creaky food supply chain was unwinding pandemic-era disruptions in 2022, two of the country’s largest grocery store owners looked around the market and figured out that if they were ever going to compete with Walmart, they would have to grow. A merger seemed like an ideal solution for Kroger and Albertsons. So after some talks, Kroger agreed to buy Albertsons for $24.6 billion in stock and cash. That deal would have created a grocery behemoth, combining Kroger’s 2,700 stores and its 9.2% market share with Albertsons’ 2,300 stores and 6.4% market share into the second largest U.S. grocery chain. (That would have still trailed far behind Walmart, which last year sold 23.6% of all groceries in the U.S.) But it all fell apart this month when a judge ruled that the Federal Trade Commission was right: The deal might be good for the supermarket chains, but it was bad for consumers, reducing the number of towns where Kroger and Albertsons compete and keep prices down. The companies had tried to pre-empt the FTC’s objections. But their plan to divest almost 600 stores to a grocery wholesaler with scant experience in retail was deemed unworkable by the judge. Now Albertsons is suing Kroger over the nixed deal, arguing that Kroger had failed to help present a workable divestment plan to the FTC because it wanted to back out of the deal. Albertsons is seeking $6 billion in damages, the premium it says its shareholders have lost because the deal was scuttled.

Source: Quartz

HEY READERS,

THANK YOU for opening the Chartbook email. I hope it brightens your weekend.

I enjoy putting out the newsletter, but tbh what keeps this flow going is the generosity of those readers who clicked the subscription button.

If you are a regular reader of long-form Chartbook and Chartbook Top Links, or just enthusiastic about the project, why not think about joining that group? Chip in the equivalent of one cup of coffee per month and help to keep this flow of excellent content coming.

If you are persuaded to click, please consider the annual subscription of $50. It is both better value for you and a much better deal for me, as it involves only one credit card charge. Why feed the payments companies if we don’t have to!

And when you sign up, there are no more irritating “paywalls”

December 2024 saw Brazil’s central bank deploying all its considerable powers and over $17 bn in reserves to halt the slide of the real.

For contributing subscribers only.

Swim Lesson, 2021. Acrylic, oil, ink, charcoal, water from the coast of Senegal, water from lower Manhattan docks, water from Lake Michigan, water from Milwaukee River, water from the Pacific Ocean, African Mahogany, and Yellow Pine on canvas. 84 × 120 in / 213.4 × 304.8 cm. Source: Interview Magazine

Almost 2 million Americans are alreaday on the new generation of weight-loss drugs.

Source: Goldman Sachs

Is the market for global corporate deal-making going to come back in 2025? Goldman is optimistic.

For contributing subscribers only.

Khari Turner Rogue waves, 2020 Epsom somerset velvet 24 × 18 in | 61 × 45.7 cm. Source: Artsy

Billy Wilder’s 1960 romantic comedy-drama, The Apartment.

Excellent Xmas viewing. The ultimate reference for Mad Men.

Monuments to meat extract: Erin Maglaque on Eating and Being: A History of Ideas about Our Food and Ourselves by Steven Shapin.

Soup survived these transformations. The chemist Justus von Liebig, who had theorised the nutritional power of protein to remake spent muscle, became obsessed with extracting the most nutritious elements of beef and turning them into broth. He was on the hunt for osmazome, a mysterious compound that made meat savoury, nutritious and, well, meaty. He came up with a recipe, worked with a railway engineer to industrialise the production of beef extract, and founded Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, which eventually became a massively profitable multinational after trademarking the Oxo cube. Mrs Beeton called Liebig the ‘highest authority on all matters concerned with the chemistry of food’, but Eliza Acton, in her popular Modern Cookery, for Private Families (first published in 1845), didn’t cut out the housewife altogether. ‘The stock-pot of the French artisan supplies his principal nourishment; and it is thus managed by his wife, who, without the slightest knowledge of chemistry, conducts the process in a truly scientific manner.’

Source: London Review of Books

Lamentable Stick Figure & Ancient Aliens by Oliver Cussen

In the 1930s, French philosophers began to examine the responsibility of humanism for the crisis of the First World War and the rise of totalitarianism. The chaos of the young 20th century couldn’t be attributed solely to the ‘death of God’; man also had to take some of the blame. Where some, like Jung, embraced the secular religions of state, nation or party, Bataille, Sartre and Levinas argued that modernity had failed because it was based on the flawed concept of the human, with innate qualities and rights. Scepticism about humanity matured into a fully-fledged anti-humanism in the wake of another catastrophic war. One year after the liberation of Paris, Sartre claimed that the ‘cult of humanism’ could only have ended in fascism; the task for postwar Europe was to reject the religious and metaphysical baggage of ‘human nature’ and to recognise that man was ‘still to be determined’. But his peers refused to accept even this minimalist defence. Claude Lévi-Strauss, in a sustained denunciation of Sartre at the end of La Pensée sauvage, insisted that the purpose of anthropology was ‘not to constitute, but to dissolve man’. Not long afterwards, Foucault identified man as the invented object of 19th-century sciences – history, biology, economics – that were becoming obsolete. The death of man was imminent and promised to reveal new intellectual and political horizons. This tradition of 20th-century anti-humanism was the subject of Geroulanos’s first book, An Atheism That Is Not Humanist Emerges in French Thought (2010). His second, Transparency in Postwar France (2017), addressed a similar assortment of thinkers and themes. The human sciences since Rousseau had claimed that self and society were essentially legible, and that knowledge could easily be communicated across different cultures. Foucault’s generation rejected these assumptions and replaced them with ‘the image of a non-human and anti-humanist complexity’ that rested on structuralist theories of power and information: language always exceeds the speaker’s grasp; norms are not natural but constructed; both self and other will always remain, at some level, unknowable. The Invention of Prehistory is something of a departure: it deals with the past two centuries, not just postwar France, and is written for a general audience. But in other respects it might be thought of as the final instalment of an anti-humanist trilogy. Taking inspiration from the protagonists of his first two books, Geroulanos insists that our flawed ideas about prehistory both rely on and reproduce essentialist concepts of the human that prevent us from taking responsibility for the present, or from thinking about alternative future. … Like the structuralist anthropologists of the postwar period, Geroulanos believes that we can neither fully understand nor escape our own codes of meaning. Whether they’re an archaeologist, geneticist or pop historian, the investigator of the deep past is condemned to use concepts that have, as he writes in Transparency, ‘a life of their own’. By this standard, even those who challenge grand narratives of civilisation head-on will remain trapped in the prison house of prehistory. … We should stop looking to people from the deep past for answers; we cannot know them and they are not ‘worthy of our love’. Better to accept that we live inescapably in our historical present, as ‘compound beings, webs of meaning, and cyborgs’. … Geroulanos’s warnings about the mythical and ideological work prehistory has been made to do are well taken. But it would be a shame to wilfully restrict our historical imagination, to accept confinement in our 21st-century webs of meaning. It might also be a mistake to abandon prehistory to racists and cranks. One of the most popular series on the History Channel in the US is Ancient Aliens, which takes its inspiration from Erich von Däniken’s theory that extraterrestrials were responsible for the achievements of early human cultures. Geroulanos would get a lot out of Ancient Aliens. A typical episode will begin by questioning the ability of ‘primitive man’ to build such complex structures as Stonehenge, the pyramids or the Nazca Lines, which could have been the work only of ‘otherworldly beings who descended from the sky’, or ‘space gods’. It will sometimes liken those achievements to the wonders of modern technology: the pyramids were power plants that distributed electricity through obelisks; the Nazca Lines are the remnants of ‘a mining operation for advanced beings in the distant past’. The show is proof of modernity’s ability to find itself reflected back wherever it looks, in the distant past or in outer space. But it also suggests that the abuses of prehistory can just as easily stem from a low estimation of humanity and an insensitivity to cultural difference. In an episode about the Moai of Easter Island, von Däniken, a frequent guest, refuses to accept that the people of eastern Polynesia would have made symbolic objects that bore no resemblance to themselves: ‘The statues they created, they have long narrow noses, narrow lips ... They look like robots.’ In any case, the monoliths are so heavy they must have been put there by a ‘more profound power’ than ‘man’s hard labour’.

Source: London Review of Book

Khari Turner Contemplation of a spotless mind 2020, Source: Daily Art Fair

Thank you for being part of this community! If you have scrolled this far, you know you want to click: