The euro is not in the headlines. On the 25th anniversary of the first moves to irrevocably fix the exchange rates of the major European economies this lack of notice is good news. For too much of its history Europe’s common currency has lived under the shadow of alarmist speculation about its future.

But though the euro’s existence is not in question, European Monetary Union remains a work in progress and its future destination an open question. Will Europe converge on the pattern laid down by the United States on its long path to a unified national monetary and financial system? Or will Europe’s trajectory and its ultimate destination be different? Can it avoid another crisis like that which shook the European economy to its foundations between 2007 and 2015?

These are questions that were debated at the launch event of the EMU Lab at the European University Institute in Florence.

Incompleteness remains the most common way of characterizing the Euro’s situation. Let us call this euro-thesis 1.

Important pieces of banking union and capital market union remain stuck at the committee stage. Europe’s common currency lacks a solid fiscal backstop and the political union that would support it.

Negotiations over banking and capital market union have been ongoing for years. The need for a substantial fiscal capacity, backed by common debt is both so obvious and seemingly so impossible in political terms that it induces eye-rolling and handwaving talk of the difficulty of “treaty change”.

But as incomplete as European Monetary Union may be, is this really its main problem? At the EMU Lab event in Florence, the FT’s Martin Sandbu stoutly defended the position that structural issues, though serious, have so far been less decisive in the Euro’s history than policy mistakes. Let us call this euro-thesis 2.

This is the argument Sandbu laid out in his important book Europe's Orphan: The Future of the Euro and the Politics of Debt. Of course, Europe would be better off with more complete institutions. But no system can easily withstand policy failure on the scale that Europe’s elite inflicted on the EU after 2007. The ECB and European governments willfully hiked interest, imposed austerity and allowed confidence in bond markets to evaporate. It was a policy mix so perverse that it cannot even be explained by the need to rescue Europe’s banks at the expense of the population at large. Europe’s bank suffered a disastrous shock after 2007 from which they unlike their US counterparts have not fully recovered. On this more in the second installment of this two-parter.

The focus on policy is convincing as far as it goes. But Sandbu’s argument has always been vulnerable to the counter that Europe’s policy mistakes were not really mistakes at all. They were perverse but deliberate choices on the part of Europe’s conservative wing, led, but not limited to Germany and the Bundesbank.

Seen from this point of view the unresolved structural issue that was truly decisive for the Euroarea was not a missing institution here or there, but the political divisions between contending schools of monetary policy. Call this euro-thesis 3.

Thesis 3 points not so much to a missing institutional layer, as to a structural political division within the project of European Monetary Union. In the early 1990s Germany political and economic elite acceded to the Euro project on the condition that the European Central Bank should be a fantasy version of Germany’s inflation-fighting monetary regime writ large. It was not so much the actual history of the Bundesbank that was the guide as a stylized 1990s archetype of an independent central bank, shorn of any direction connection to national Treasuries and limited by law in its ability to manage sovereign debt markets - the function for which central banks originally came into existence. The other members of the Euro went along, because the Euro could not be worse than the lopsided European Monetary System that since the 1980s had subordinated them de facto to Bundesbank policy. Furthermore, they hoped that in due course they would either be able to grow up to withstand the pressures of German-style monetary policy or modify the “Bundesbank model”, in ways that would make it more suitable to the needs of the diverse European economy.

It was the struggle over the terms of this compromise and the lack of trust and agreement (thesis 3) that sets the stage for the policy mistakes that Sandbu highlights (thesis 2) and limits the possible progress on further institutional development (thesis 1). In gauging the future prospects of EMU, if we follow thesis 3, the crucial question is how far we expect the power struggle to be resolved and which side wins.

At the ECB, Mario Draghi’s leadership from the end of 2011 seemed to signal the beginning of a new era. His promise, in August 2012, to address the ongoing crisis in European sovereign debt markets by doing "whatever it takes” and the decision to actually begin large-scale bond-buying in 2015 provoked outspoken but unavailing conservative protests.

But though Draghi won battles for the cause of pragmatism and flexibility in the management of Europe’s economy, the war is not over. In 2019 there was an anxious moment when it seemed that Angela Merkel’s government in Berlin might want seriously to push the candidacy of the hawkish Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann to succeed Draghi at the ECB. Christine Lagarde won out, but when she took office in October 2019 she faced a hail of vituperative criticism nominally triggered by the ECB’s latest round of bond-buying, but actually expressing a broad current of conservative resentment at the new dispensation.

Nor, in the period between 2015 and 2019, did the ECB receive support from European fiscal policy in addressing what was then the lurking menace of deflation. Proposals for common EU spending programs pushed by France and other member states did not meet with a warm reception in Berlin. When COVID hit Europe in February and March 2020 it seemed as though a rerun of the eurozone crisis was on the cards. What seemed likely at first was that both monetary and fiscal policy would fail to respond.

But then they didn’t. Days of panic in the bond markets and the example of the Fed were enough to swing the ECB into action. A few weeks later Berlin and Paris agreed to what would become the common borrowing program known as NextGen EU with the Recovery and Resilience Fund at its heart. In 2020, faced with COVID, the EU failed to fail.

How to make sense of this turn away from disaster?

The optimistic reading is that faced with the pandemic the balance of political forces in Europe and in particular in Germany shifted in favor of Common European action (thesis 3). There was policy learning from the disasters of the era of Eurozone crisis (thesis 2). The two together enabled a process of institution-building in the form of NextGen EU. This is very much the spirit in which Jonathan Zeitlin, David Bokhorst and Edgars Eihmanis analyze Governing the RRF (Recovery and Resilience Facility)

But not only are there serious questions about the legitimacy, effectiveness and ambition of the many national Recovery and Resilience Plans, there are also ambiguities at a more basic level. Europe’s governments interpret the new policy institutions and processes created in 2020 very differently.

One wing of European politics, concentrated on the progressive side in France, Spain and Portugal would like to see NextGen EU as a precedent for further institutional growth. On the other hand, the German government under Merkel insisted on viewing it as an exception and this remains the prevalent view in Germany, an interpretation recently reinforced by a judgement of the constitutional court in Karlsruhe on Germany’s domestic fiscal policy.

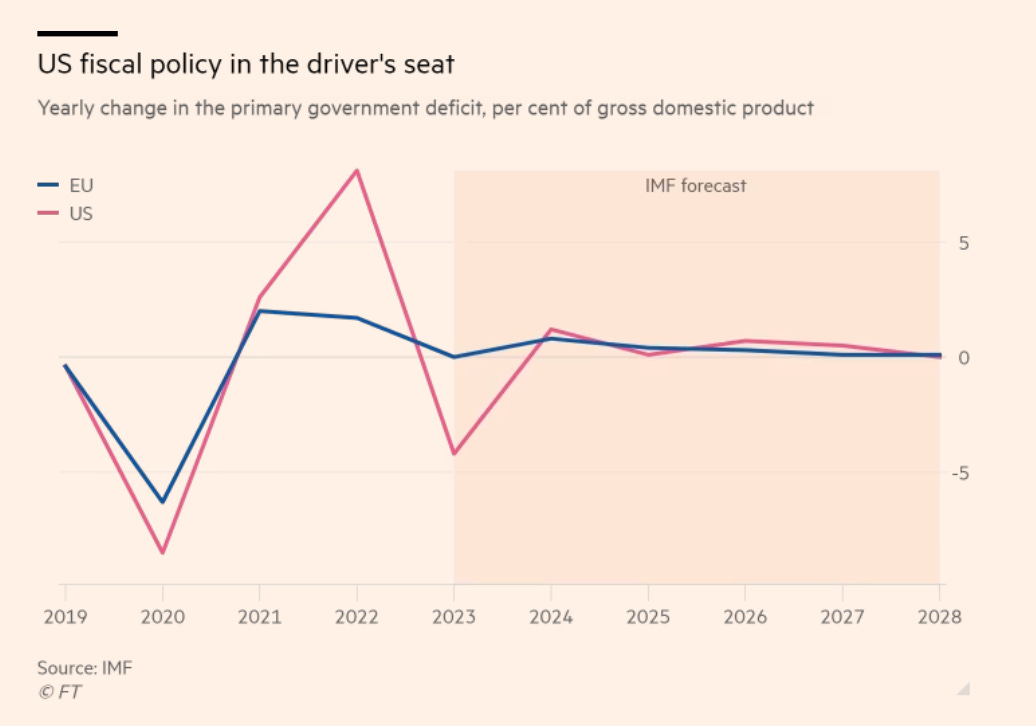

For all the innovative techniques put to work in implementing the Recovery and Resilience Programs, the fiscal impulse delivered in Europe has been modest. As Martin Sandbu showed in a recent piece, compared to the dramatic stimulus delivered by the US, it is notably unambitious.

Relative to the US, for all Europe’s failure to fail, it is losing the race to recovery.

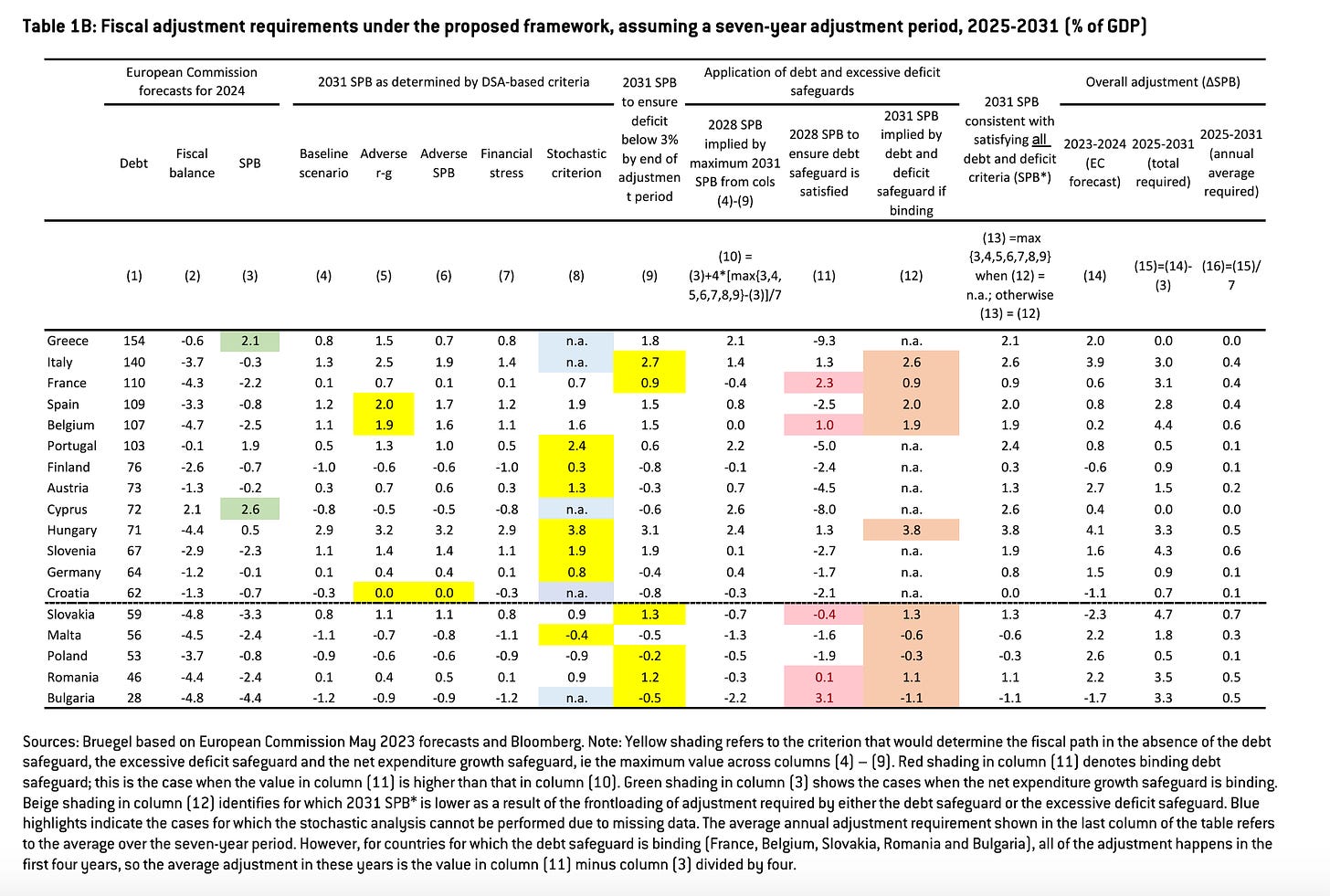

And far from seeking to redress this lagging recovery, the attention of European policy-makers has of late been concentrated on perfecting a new generation of fisacl rules. Though the resulting compromise is hailed as more flexible, simulations by Zsolt Darvas, Lennard Welslau and Jeromin Zettelmeyer at the Breugel think tank make clear the severe implications for fiscal policy, notably in the most debt-stressed European states.

The terms are better than under existing rules, but for Italy they remain impractical. From 2025 Spain and Italy are required to achieve and annual structural tightening of 0.6 percent. Investment spending is not specially protected. As Philipp Heimberger points out in Handelsblatt this is not a forward-looking European economic policy, but a return to austerity that must incite political conflict.

Rather than an upbeat theory of learning, what seems more compelling to describe this messy set of compromises is the model suggested by the fascinating essay “Maintaining the EU’s compound polity during the long crisis decade”. by Maurizio Ferrera, Hanspeter Kriesi & Waltraud Schelkle.

Rather than simply parroting the familiar phrase from Jean Monnet that Europe is the sum of the solutions found to its crises, they seek to explain why Europe develops through repeated crises and its repeated failures actually to collapse.

Their argument is that Europe’s political class has developed a tool kit of three types of response to the crises produced by external shocks and its internal contradictions. In the process they, argue, Europe’s political class have turned the “very same features” into “contingent sources of political strength that most scholars diagnose as determinants of failure.”

One tactic in the toolkit of modern European politics is to raise rhetorical-political appeals in moments of crisis, Draghi’s “whatever it takes” being the classic case in point - a political promise unbacked by actual authority or technical agreement. Another is to externalize the problem - most notably in the case of the refugee crisis, which in the name of restoring control has been externalized to Turkey. But most interestingly of all, Ferrara, Kriesi and Schelkle argue that Europe’s weak center - one of its basic structural flaws - provides incentives for energetic action at moments of crisis by national governments. As they summarize the logic of this argument:

But as Ferrara, Kriesi and Schelkle go on to argue, the crisis-driven logic of European politics acts in ambiguous ways. Raising the rhetorical stakes promises great strides forward. Externalization releases the pressure for internal change. Meanwhile, lurching moves towards the center at moments of duress do not overcome basic disagreement over the direction of European integration and the pro-market bias of the Treaties.

As they conclude, “the outcome of this uphill struggle is open-ended. Between outright failure and deeper integration there is also an intermediate scenario: resilience without ostentatious change. And this can mean gradual constructive transformation or mere survival in anticipation of the next crisis.”

This seems a truly apt characterization of Europe’s position at this moment, at least from the side of policy and governance institutions. But that is also the chief limitation of these sophisticate arguments. They focus on policy and governance and not on what it is that is being governed, the stuff of the European economy and society, European capitalism and financial capitalism in particular. And yet, to start from the premise that the central problem of the Eurozone in the last 15 years has been the problem of public debt and policy is to accept the bait of the conservative interpretation. In fact, the existential crisis of the Eurozone crisis began not with Greek public debt but with the North Atlantic banking crisis that first exploded on the balance of the French megabank Paribas in the autumn of 2007. To believe that the question of central bank independence and the threat of fiscal dominance were the main issues for the architecture of the euro to address, was the chief design mistake made at its foundation. Are we repeating that error in our diagnosis today, or does the humbled position of Europe’s banks imply that they pose no systemic threat today? These are the questions I will turn to in part 2 of this mini-series.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here.

Many thanks for reading!

In the final paragraph I think you hit the crucial point: all of the sturm und drang around "saving" a structure that is inimical to human flourishing for millions of citizens across the nations of Europe is a distraction from the the violence that is imposed upon them -- as much by the architects of the neoliberal dystopia as by those entrusted with sustaining it.

We used to have a name for these people: aristocrats -- and we used to have a solution for them: revolution ...

I witnessed the influence of Jens Weidman and the position he adopted on interest rates and debt in the Eurozone in the late noughties and early 2010s in G20 negotiations when he was Germany's sherpa (and I was his South African counterpart). I witnessed how Europe refused to allow discussion of the debt crises in its South in those meetings when other parts of the world, including the US under Bush and Obama, were far more open. It struck me as unhealthy defensiveness. Thank goodness he did not succeed Draghi.