The World Bank's CEO lab, underpaid teachers, Marxist politics and crises of capitalism

Great links, images and reading from Chartbook Newsletter

Thank you for reading Chartbook newsletter.

Carlo Levi, Lucania, 1961, Lanfranchi Palace

Carlo Levi (1902-1975) was born in Turin, nephew of a socialist leader, and graduated in medicine in 1924. The same year he exhibited expressionist paintings at the Venice Biennale, and joined anti-fascist groups. In 1935 he was exiled for his determined anti-fascist organizing, to Italy’s rural and impoverished southern Basilicata region - also known by its ancient name, Lucania - where he produced one of the classic novels of political ethnography of the twentieth century, Christ Stopped at Eboli, and also a series of paintings. This painting is part of a retrospective tryptich of panels dedicated to Rocco Scotellaro, writer, poet and mayor of Tricarico. He appears here very young, in the center of the canvas, with a red face due to malaria. He is portrayed as a former mayor in the center of the square, crowded by his community in which important Italian intellectuals also participate, including Umberto Saba, Renato Guttuso and Levi himself. In the two images below, the other parts of the tryptich include distinct communities of women and of children suffering in the region. In 1963, two years after painting this vista of southern poverty, Levi entered the Senate. He was elected on the Communist Party ticket, though not himself a member.

Glad you enjoy reading the newsletter. What sustains the project are subscriptions from readers like you, who get lots of extra content too.

Capitalists and global institutions - usually in the driving seat…

When the UN held its general assembly last week, the attention of the media — and the protesters — was mostly focused on the politicians. But in its shadow, another event was taking place which investors would do well to note: a recently formed “private sector investment lab” for the World Bank held its inaugural meeting to discuss how to turbocharge the Bank’s operations. This 15-strong body — which features chief executive officers such as Axa’s Thomas Buberl, BlackRock’s Larry Fink and Ping An’s Jessica Tan — did not issue any public report; nor did its co-chairs, Mark Carney, the former central banker, and Shriti Vadera, chair of Prudential. However, I am told that these chief executives are brainstorming a swath of proposals for the Bank. And what they decide to do could be critical in determining whether the institution can make itself more relevant and credible under its new president, Ajay Banga.

Gillian Tett in FT

An isolationist reality?

Subscribers only

The hollowing out of teacher pay

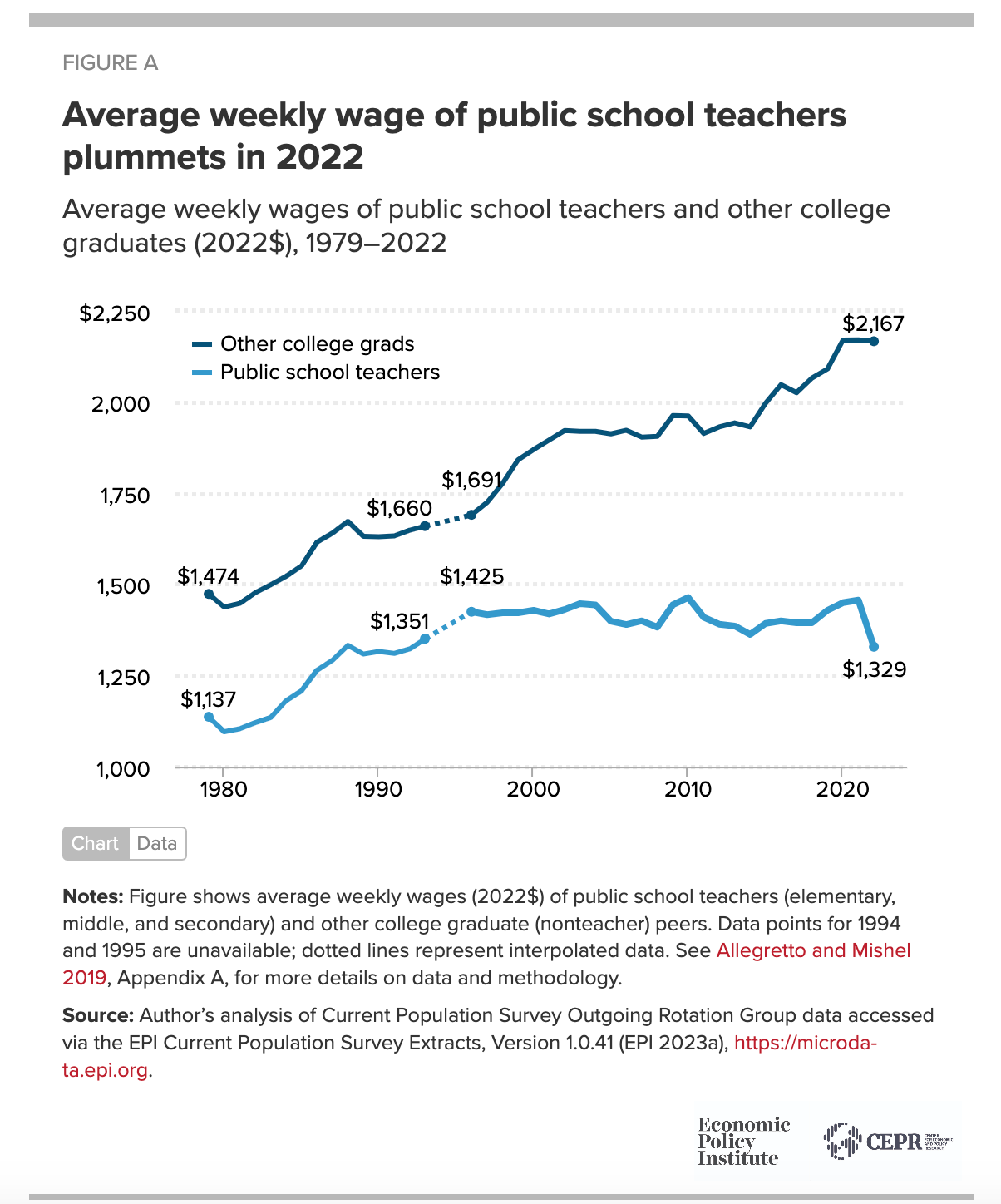

The pay penalty for teachers—the gap between the weekly wages of teachers and college graduates working in other professions—grew to a record 26.4% in 2022, a significant increase from 6.1% in 1996:

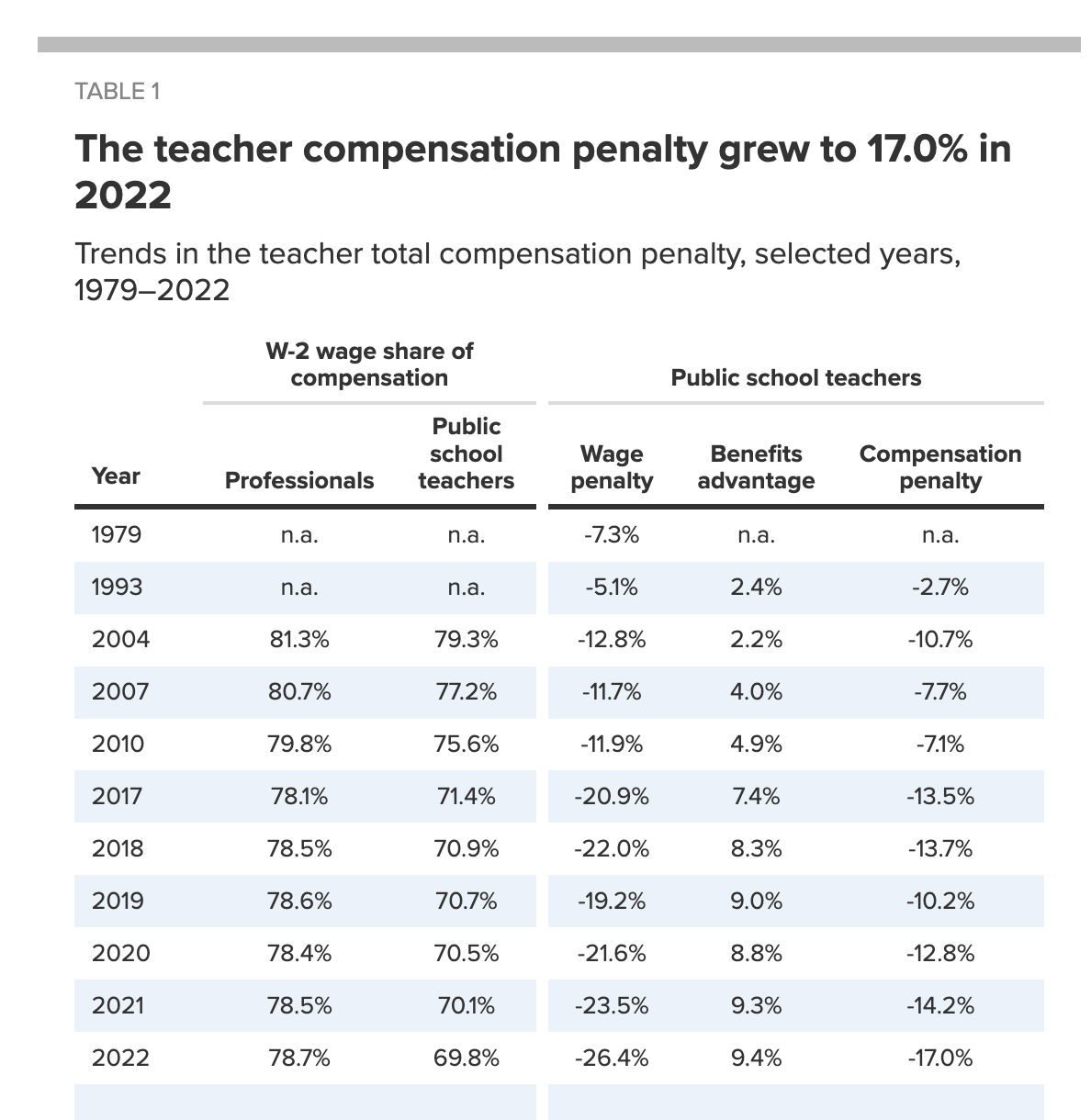

Although teachers tend to receive better benefits packages than other professionals do, this advantage is not large enough to offset the growing wage penalty for teachers:

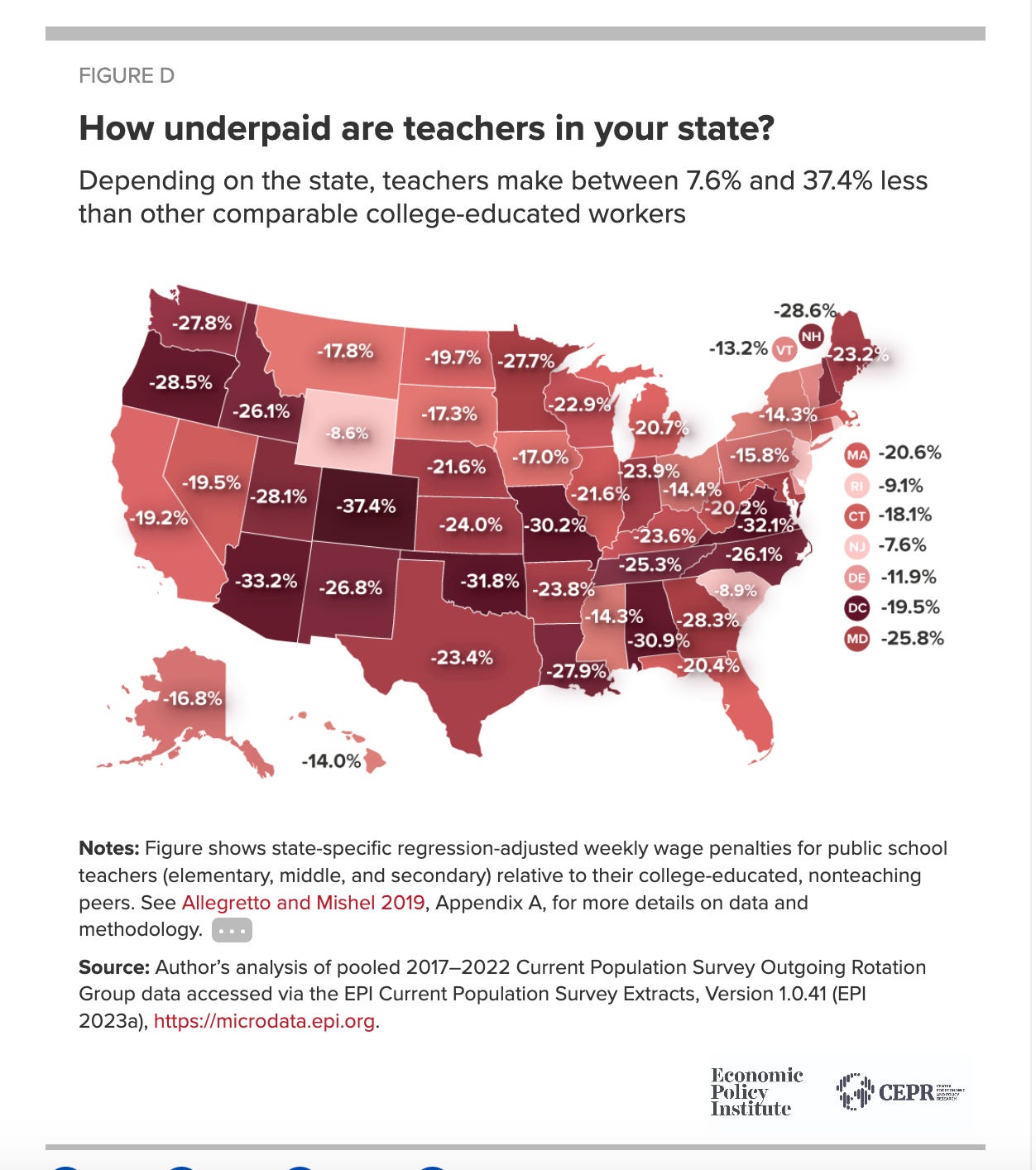

On average, teachers earned 73.6 cents for every dollar that other professionals made in 2022. This is much less than the 93.9 cents on the dollar they made in 1996. The story has some partisan political component, it is worst in deeply Republican states where Galbraith’s general truth (America has “private affluence and public squalor”) is most extreme in the hollowing out of the public realm, including education:

Source: Sylvia A. Allegretto, EPI

To join the supporters club and get the full Top Links service daily to your email inbox, as well as longer analyses explaining everything from war in Ukraine to American car strikes, click here:

A conservative Court and the state

Subscribers only

Gangs as employers

Subscribers only

Monetary dynamics of the Nazi occupation of France

Subscribers only

French full employment

Subscribers only

Are we all reformists now? The political stakes of crisis theory

With contribution from Barnaby Raine

Over at Jacobin magazine, one project in the making of the contemporary American Left: a group of smart young socialists energized by Bernie Sanders have in recent years insisted on the possibility of social democracy in America, eclipsed (on this view) by a nay-saying coalition of ideological orthodoxy extending from the American mainstream to the small radical Left, where classic welfarist reforms like universal healthcare have long been thought supremely unlikely to traverse the high roadblocks of class power and the undemocratic state structure in the world’s passing imperial hegemon. Hence, for the Left, some kind of revolutionary rupture has appeared as the only way out. In offering systematic intellectual foundations to this story, Jacobin authors have sometimes turned to history, first via the epoch of the Russian Revolution: finding in Karl Kautsky’s slow march to socialism and in Finland’s democratic 1917 a more plausible model for the present than Lenin’s traditionally influential philosophy of militant leaps and insurrection. Adding to these foundations, Jacobin’s Seth Ackerman now takes on an influential account of the political economy of our present — the theory of capitalist stagnation since the 1970s authored by the UCLA Marxist Robert Brenner. On the social democratic view, that story is troubling for ruling out easy reforms of the kind possible when the 1945-73 period left large surpluses to redistribute. Ackerman writes:

When looking back at these debates, what comes into view is the perennial reflex, among Marxists of a certain mindset, to judge theories of crisis according to a criterion of nonreformability: the source of crisis must be something that can be plausibly depicted as ineradicable without some unspecified revolutionary supersession of the existing mode of production. … Now, there are sensible reasons to expect economic crises under capitalism to arise from forces that reflect the vested interests of capitalists themselves in one way or another — in which case, attacking the roots of crisis requires attacking capitalist interests. But actual nonreformability turns out to be a maddeningly mobile target.

In the resulting narrative, Brenner’s prior political commitment to the path of revolutionary socialism distorts his analytical conclusions by demanding that he must identify crises of capitalism that leave no reformist way out, thus offering firm intellectual support to the case for revolution once the apparently easier path of Keynesian reform to redistribute wealth and secure full employment fades from possibility. This is a charge, then, that the politics is illicitly determining the analysis - a charge that feels more Weberian than Marxist. The battle to define the next generation of American socialism is in evidence here. One of Brenner’s leading young students, Aaron Benanav, debated Ackerman on a podcast influential for this section of the Left, hosted by Doug Henwood. Benanav has now written a forceful essay in Jacobin replying to Ackerman. Implicitly, he flips the charge about political commitments muddying analysis: he suggests that long-run capitalist stagnation troubles plenty of non-Marxist accounts now too — that it is an observable phenomenon — so that Brenner does not force the facts into a theory of necessary capitalist decline, but rather observes a recent (and actually, to him, a surprising) historical tendency which social democrats find reason to obscure. The last section of Benanav’s essay is especially interesting for pointing beyond reform/revolution binaries that say little to the concrete challenges of American politics, since communist insurrection is hardly on the horizon. Instead, Benanav makes the supposed fact of a shrinking capitalist pie crucial to a more grounded, realist interest in reform and social transformation:

By contrast, during systemic downswings, capitalists’ rates of profit fall. Capitalists are more likely to undercut one another through nasty price competition. They are also less willing to share the more meager gains of rising productivity with workers or the broader society, so wages stagnate, and so do tax takes…

The upshot is that, in downswing periods, advocates of compromise with capitalists mostly just organize the defeat of the working class. Does this theory feel so out of step with what has happened since 1973? Trades unions lost a lot of support as they stopped fighting for working people and instead organized the working-class defeat. The same is often said of social democratic and labor parties: they stopped fighting for people and instead organized their defeat. Where Brenner got it wrong was in his hope that workers might break free of these organizational constraints.

Still, maybe that has finally started to happen over the last ten years, as indicated not only by a rising curve of social unrest, but also by the rise of democratic or rank-and-file unionism. The recent victory of democratic unionists in the United Auto Workers, which was immediately followed by a combative strike, is a pertinent example.

On this retelling, the question is not whether workers can hope to gain something from capitalists, but what path those reforming gains must take: in a period where capitalists are not seeing sustained growth, the path must involve greater confrontation than in the trentes glorieuses of rising real incomes amid high profit rates after the Second World War. Benanav wants a green plan for production that involves far greater democratic control than in “technocratic” Keynesian planning. That democratic element, mobilizing working class energies, is crucial to achieve a more equal society since:

to the extent secular stagnation persists, getting there will require significant reductions in elite incomes, which will call forth gigantic resistance.

This is the reworked politics of reworked debates; socialists no longer debate crises of capitalism in order to identify a terminal point demanding revolution, as in Ackerman’s picture of 1970s debates on the falling rate of profit, but instead divide over what kinds of openings contemporary capitalism provides for what kinds of reforming struggles. Benanav seems cautious in his piece about judging Bidenomics now, but this would seem to be a key instance of the divide; can a technocratic plan ensure green investment with sufficient buy-in from capitalists to ensure the project stays afloat, or can capital scarcely afford that, so that a mobilized working class must eat further into profits and transform investment into a public function against immediate capitalist resistance, to have any hope of offering richer, more stable, less burdensome, freer lives to millions? Though Benanav explicitly denounces “economistic” readings of the challenge, his focus is mostly on employers. In an age of “abolitionist” politics against police and prisons and the waning of American imperial power globally, one question that lurks for both Jacobin contributors - and which Benanav’s model might be more able to answer - is how socialist advance might require confronting not just private capital but the domestic and international machinery of the American state too.