“Soft”, “slow” and “scarred” are three terms that stick out in the latest World Economic Outlook report released by the IMF yesterday.

Soft …

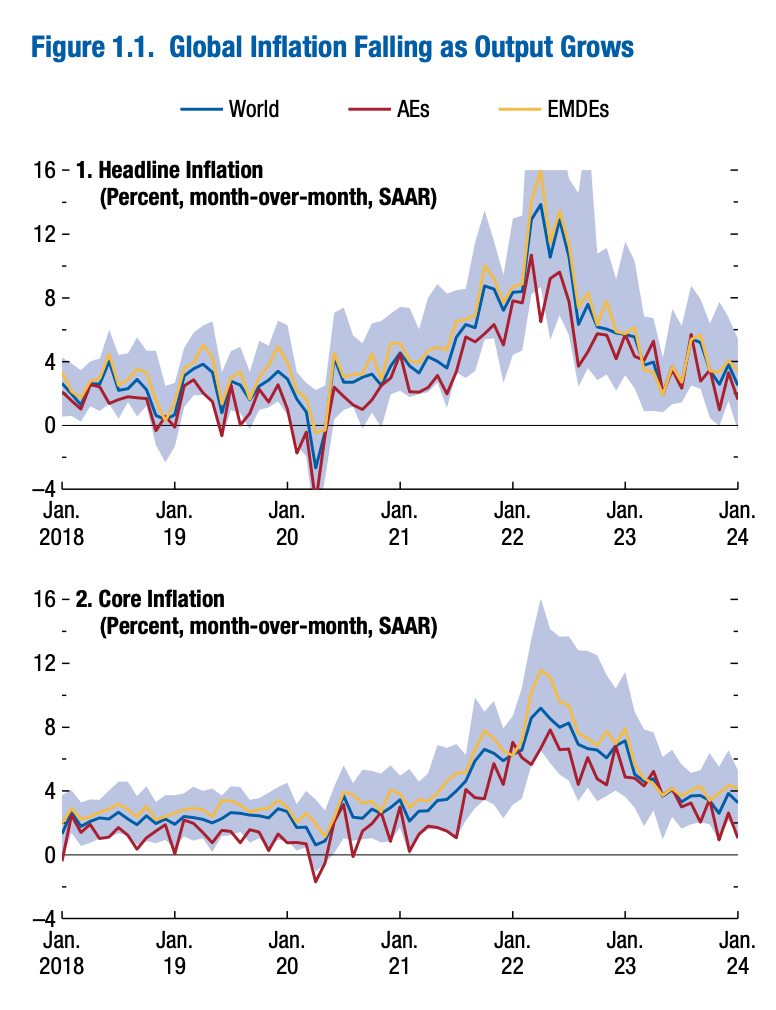

We are in the midst of a soft landing. From 2021, prices surged and the pace of increase is now slowing. And this is happening without a recession.

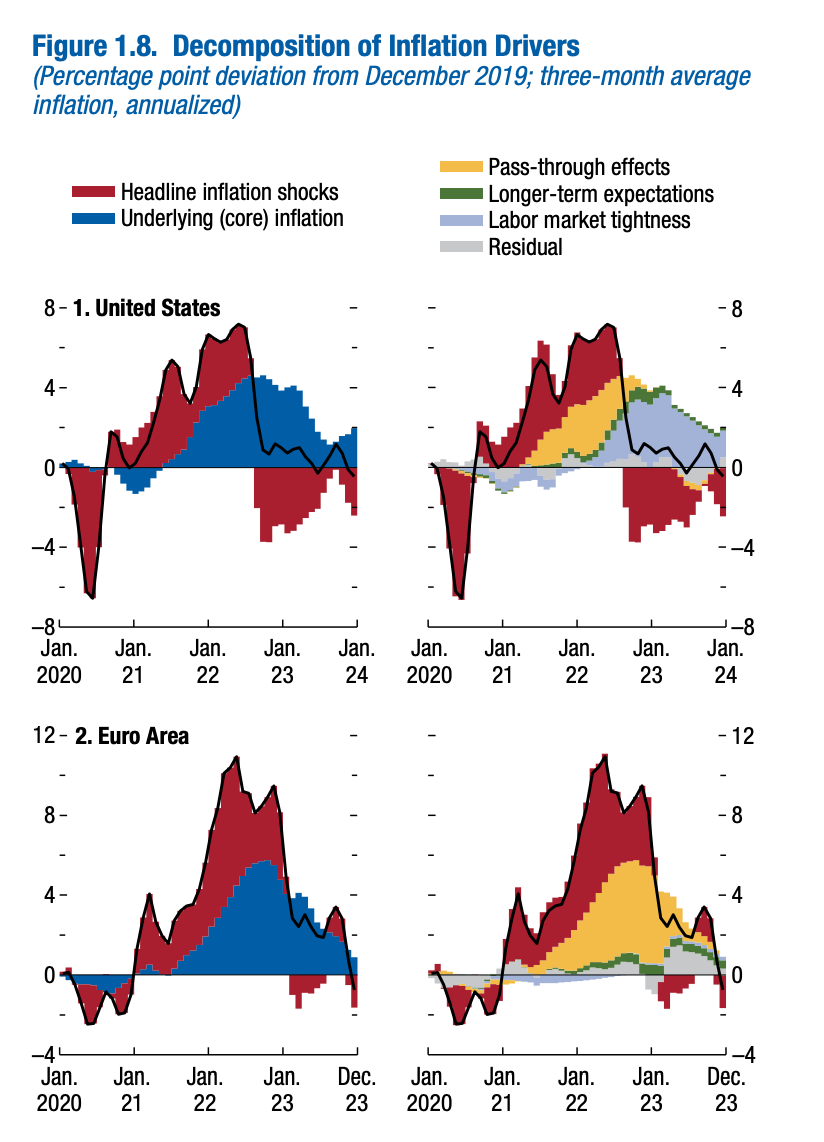

I’m speaking of prices surging and deliberately trying to avoid the use of the word “inflation”, because, in the end, the COVID-induced dislocation never did give rise to comprehensive inflation, or at least the major component of the price increase was not that of a general inflation.

Most strikingly, despite much fear-mongering, in Europe one important group of prices never became a significant driver of inflation - wages.

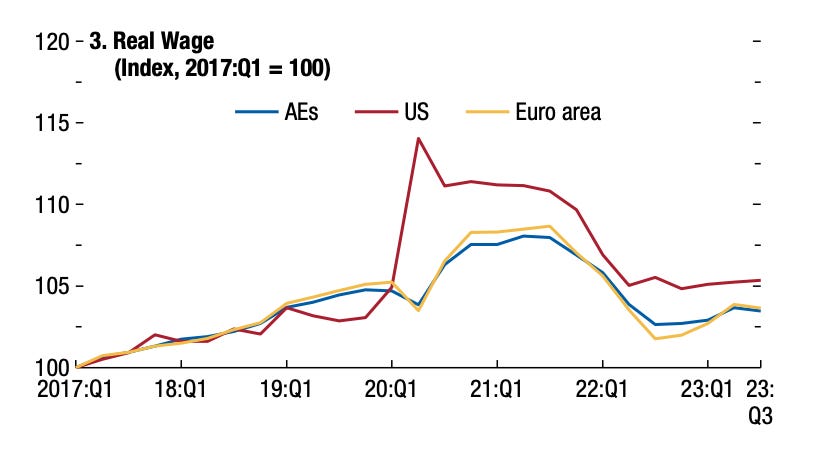

Overall, the effect of a price shock without a major wage-price spiral was to inflict a one-off hit to real wages.

Unsurprisingly, given this data, labour markets are tight on both sides of the Atlantic. As conservative readings of Keynes have always suggested, a stealth cut to real wages through an aggregate demand shock that raises prices whilst wages remain sticky, results in higher levels of employment.

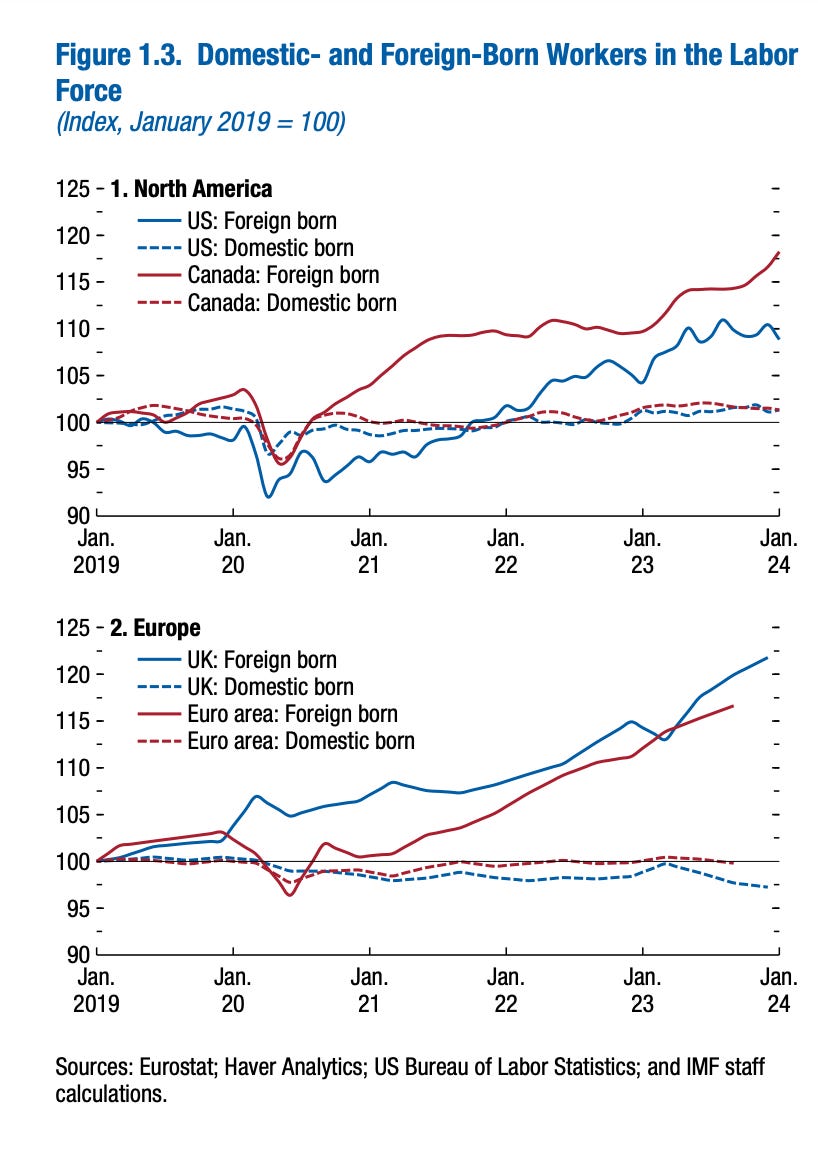

In both the USA and the EU, it is above all foreign-born workers who have carried the surge in employment. As COVID-era travel restrictions were lifted, a surge in labour migration was driven by idiosyncratic regional shocks - Ukraine and the crises in Central America. The good news is that the migrants entered tight labour markets. It would have been a far nastier scenario, if as in the 2010s, migrant push factors had coincided with slack labour markets.

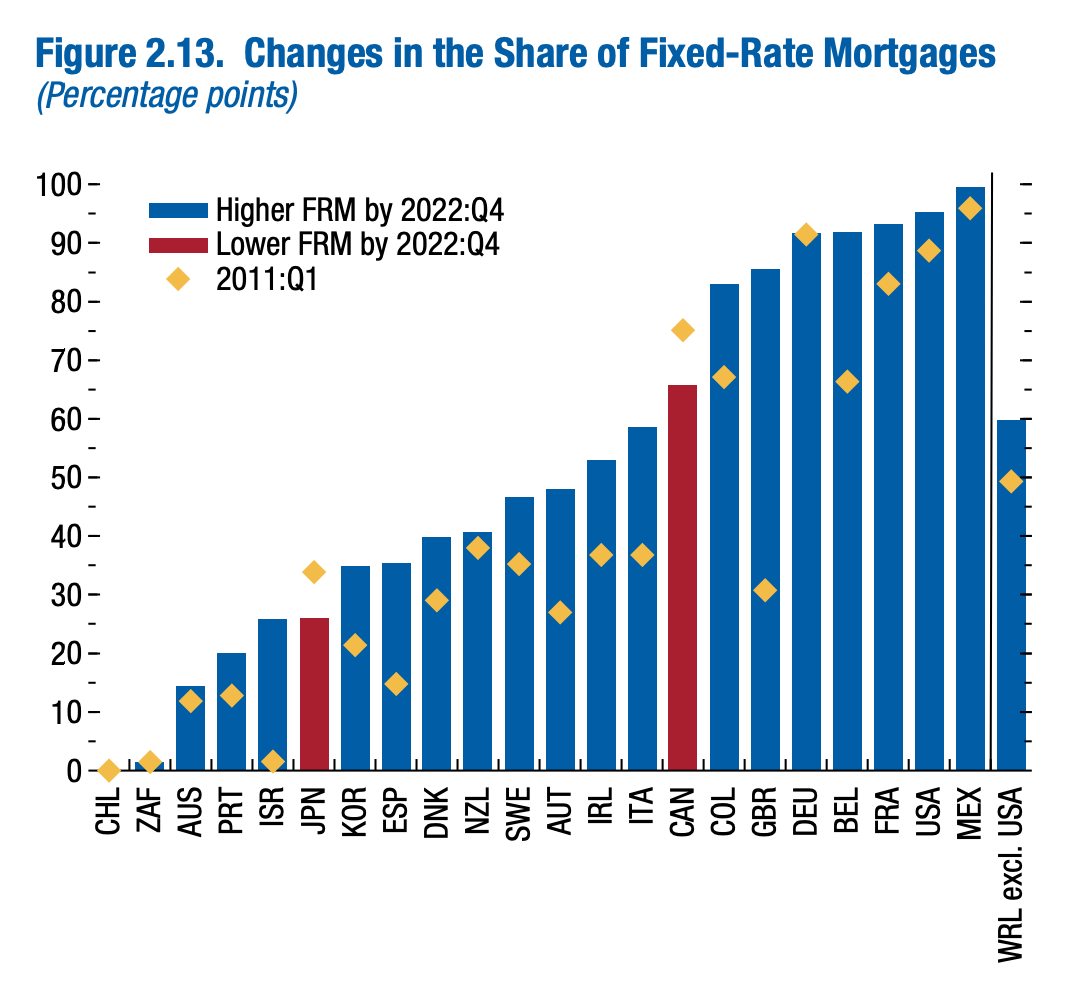

How significant was the role of policy in achieving this desirable combination of “disinflation” without recession? Fiscal policy was powerfully supportive notably in the United States. Central banks raised rates sending shock waves through financial markets. But, in a special chapter on housing and interest rates, the IMF gives reason to doubt that the housing channel was as important as it once might have been in cooling the economy.

In many large economies, most people have fixed rate mortgages. So the main effect of raising interest rates is not so much disinflation as to gunge up the housing market with homeowners unwilling to sell and move for fear of having to take out new mortgages at painful rates of interest.

Slow

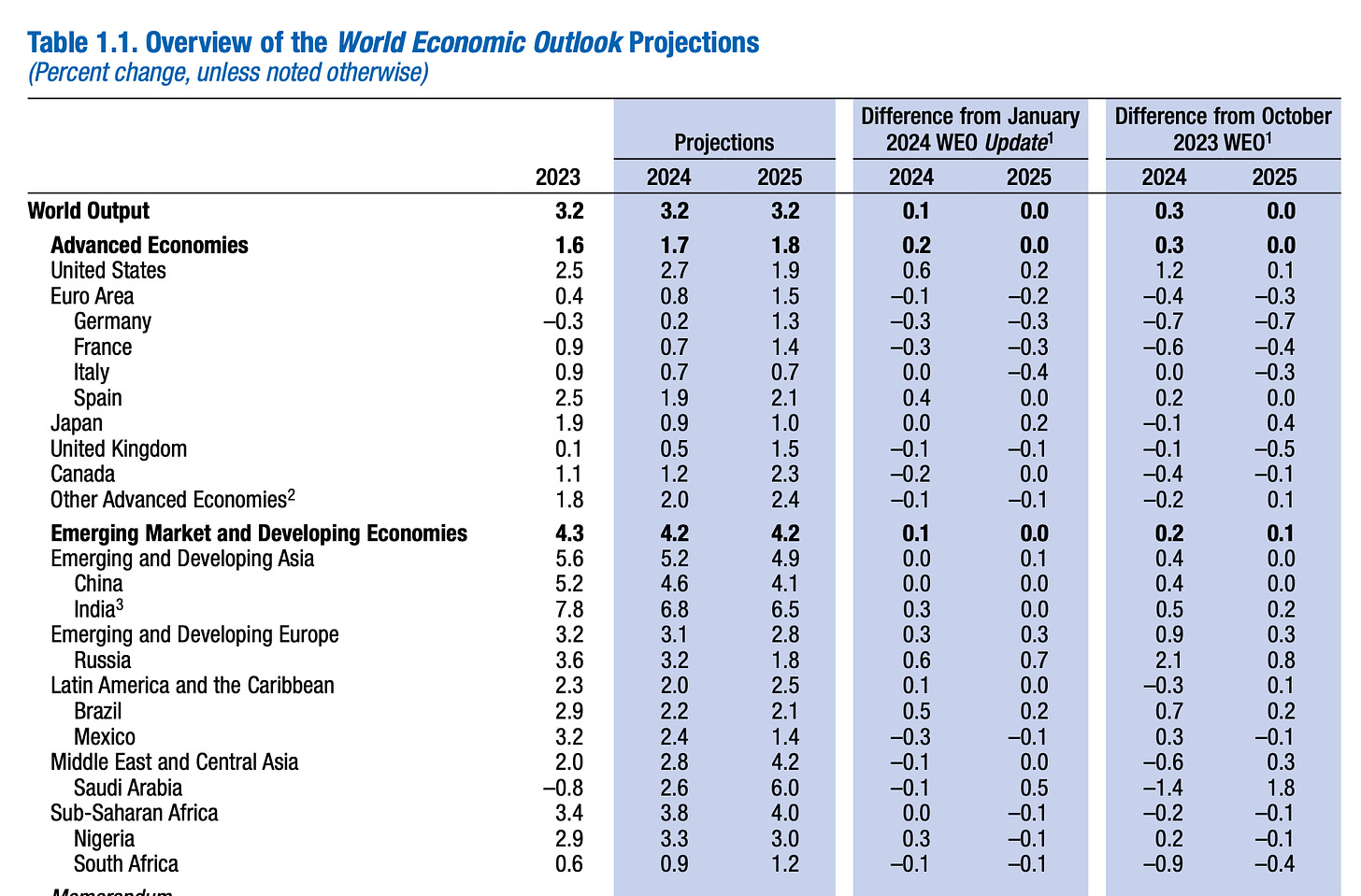

Despite the successful recovery from COVID, the overall pace of growth is disappointing, slightly less so than was expected amidst the gloom of last autumn, but still slow by historic standards.

Global growth, estimated at 3.2 percent in 2023, is projected to continue at the same pace in 2024 and 2025. The forecast for 2024 is revised up by 0.1 percentage point from the January 2024 World Economic Outlook (WEO) Update, and by 0.3 percentage point from the October 2023 WEO. The pace of expansion is low by historical standards, owing to both near-term factors, such as still-high borrowing costs and withdrawal of fiscal support, and longer-term effects from the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; weak growth in productivity; and increasing geoeconomic fragmentation. … The latest forecast for global growth five years from now––at 3.1 percent––is at its lowest in decades. The pace of convergence toward higher living standards for middle- and lower-income countries has slowed, implying a persistence in global economic disparities. …dimmer prospects for growth in China and other large emerging market economies, given their increasing share of the global economy, will weigh on the prospects of trading partners.

The outlook for Europe is particularly dim.

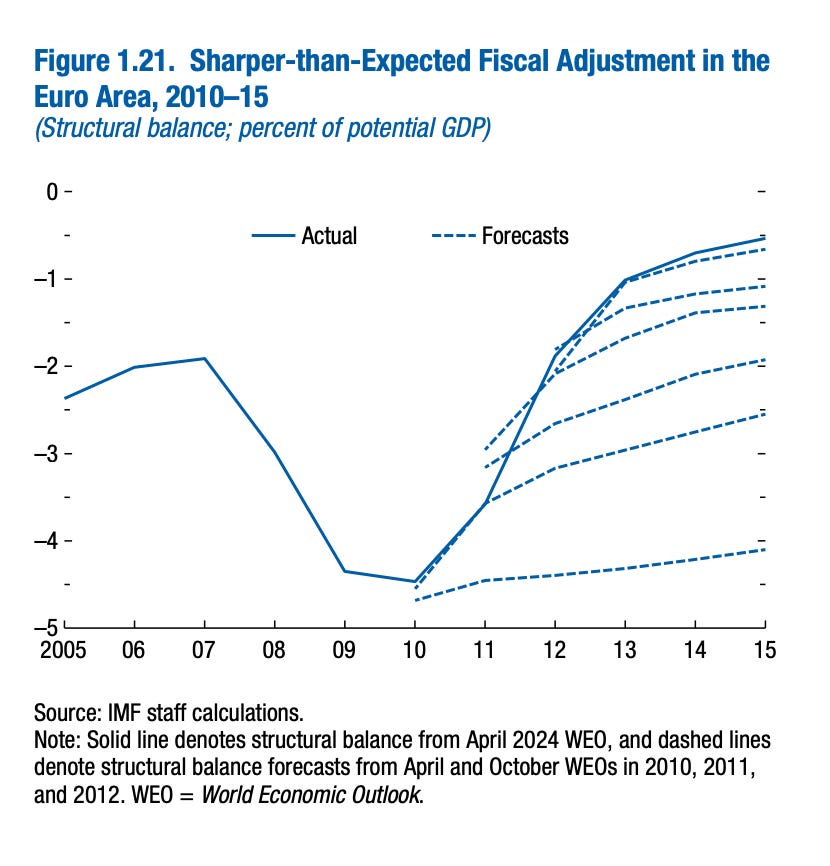

One thing that would make it even dimmer is if Europe’s fiscal hawks get their way and impose an even more severe fiscal consolidation. A striking graph in the 2024 WEO, which one imagines a worried European may have slipped into the mix, gives a graphic illustration of quite how shocking the European fiscal contraction was over the period 2010-2015. Over and over again, it outdid the IMF’s own forecast.

Unsurprisingly, a fiscal adjustment of this ferocity resulted in a lost decade for much of Europe. One concern today must be excessive fiscal tightening - driven by policy or borrowing constraints - may compound the damage done to much of the world economy by the COVID shock.

Scarred

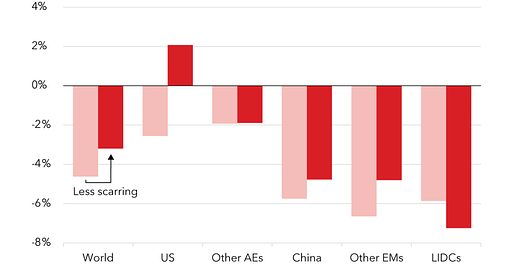

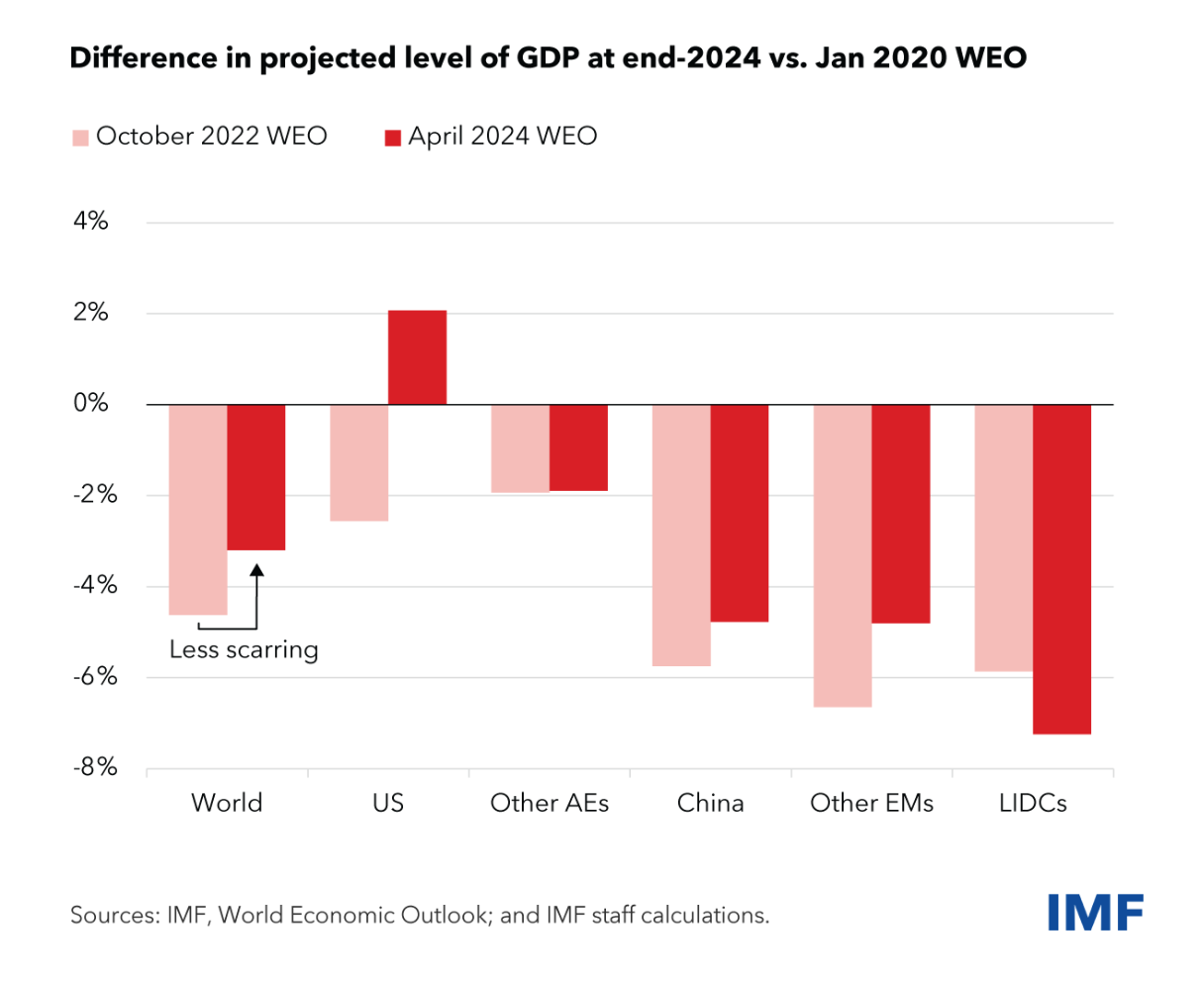

With the exception of the United States, the rest of the world economy suffered serious damage from the COVID shock - also called “scarring”. We can see that by comparing the outlook for the end of 2024 today, with IMF forecasts of the future made in January 2020.

Why did the advanced economies do better? In January 2020 the advanced economies were expecting more modest growth. In the face of COVID they were able to deliver more powerful offsetting policies. They are structurally favored in financial and commodity markets. Add all that up and in the case of the United States, by the end of 2024 we now expect it to come out ahead of where it was originally expected to be. The net effect of the COVID episode is a higher level of economic activity than was forecast in January 2020. Not so much scarring as hyping. “American exceptionalism” is the talk of the town.

Other advanced economies - principally Europe and Japan - have not done quite so well. But the damage is limited to two percentage points.

For low-income countries the scarring effect of COVID - the diversion from the track of development expected in January 2020 - is three times as large as in Europe. Furthermore - and this is one of the nasty surprises of the new WEO - for low-income countries our estimate of the scarring has actually deteriorated since October 2022. Immediately after the end of the pandemic we thought the LIC would suffer a 6 percent hit. Following the price shock and the surge in interest rates in 2023, the IMF now estimates that low-income countries will be thrown off course to the tune of 7 percent.

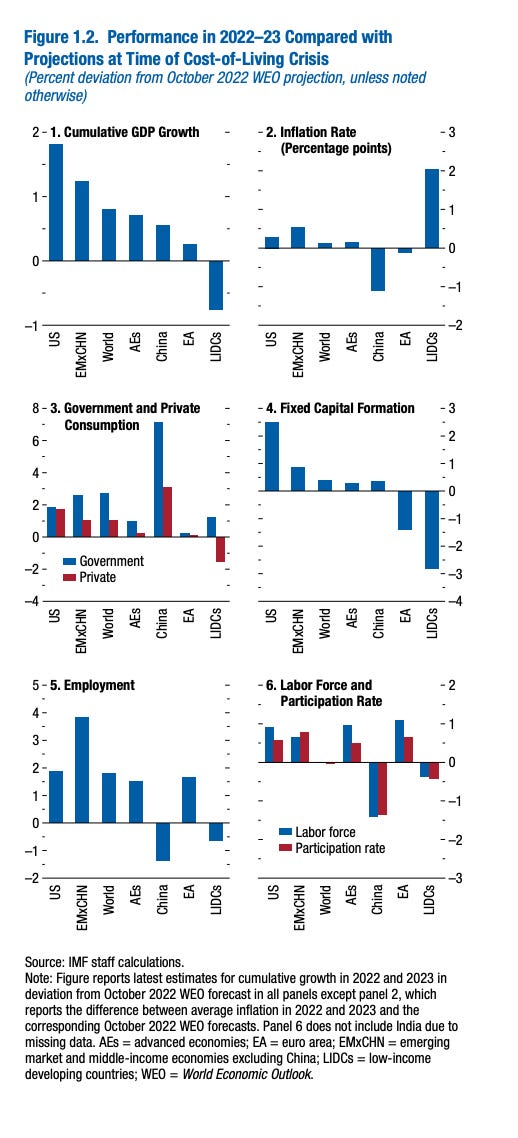

For low-income countries, there is no soft landing. Every indicator - growth, inflation, private consumption, capital formation, labour force and employment has headed in the wrong direction.

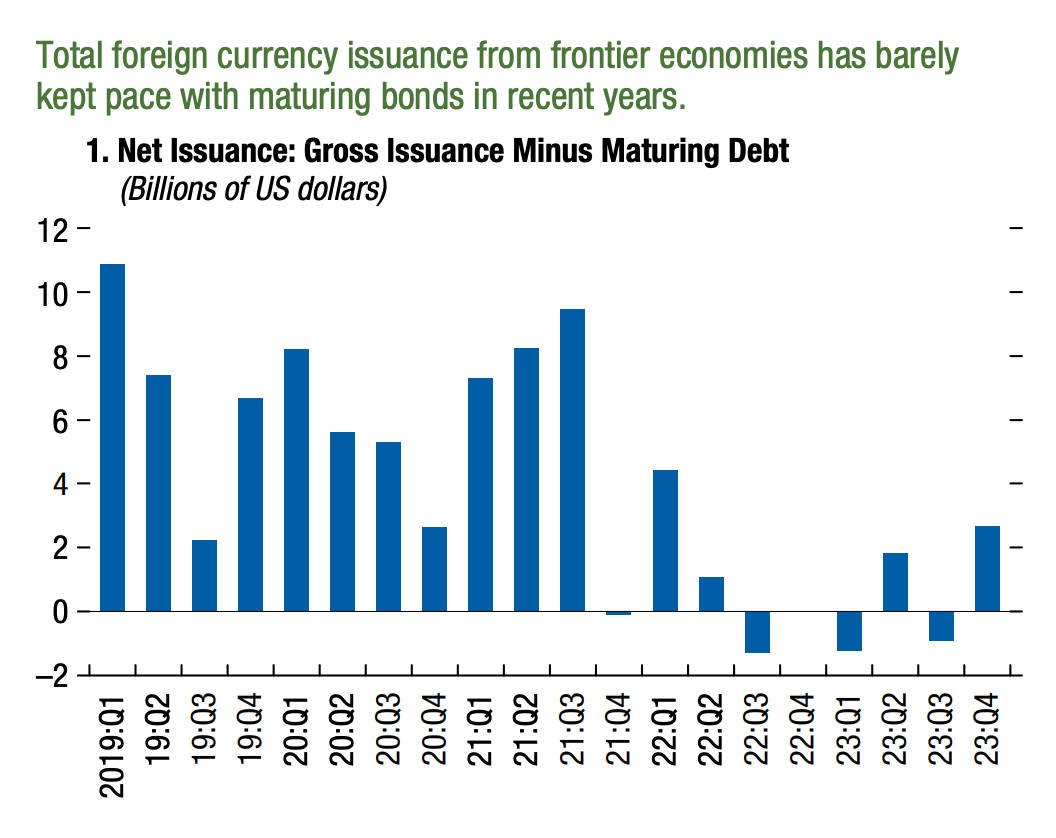

Nor is there much prospect of relief for the most fragile economies in the world. As a graph in the IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report spells out, for frontier markets the flow of net new finance through bond issuance effectively dried up at the end of 2021.

Of late there has been some sign of recovery in global capital flows. But the latest series of shocks that point to higher rates in the US for longer and a stronger dollar should be worrying for anyone concerned with development, global growth and convergence. As the IMF points out in a special feature on private credit, which I will review in a subsequent newsletter. For privileged advanced economy investors, there are many “easier” places offering handsome rate of return than “frontier” markets.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

IMF predicting that Russia will grow faster than all advanced economies in 2024! Also their largest upward revision. Not a good look.

That chart showing the US beating the world in post-Covid recovery would make a nice ad for Biden, if American voters didn't hate charts and graphs and facts generally.