With the war in Ukraine grinding on and the French election heating up, for #3 in the three part exchange between the Chartbook and the FT’s Unhedged newsletters, our minds turned to Europe.

What happens, we asked ourselves, if you put the question of Europe’s future in market terms? Since 1999 Europe’s equity markets have lagged far behind those of the United States. That is a worry for investors. But it also means that the balance of global capitalism has shifted dramatically away from Europe.

As the Economist recently pointed out: “At the start of the 21st century 41 of the world’s 100 most valuable companies were based in Europe (including Britain and Switzerland but excluding Russia and Turkey). Today only 15 are.”

Will the downward trend continue, or might it be reversed?

Over at the FT’s Unhedged I take a skeptical view. Macroeconomics, and lagging technological development aside, I don’t think there are political majorities to be had in Europe for the kind of pro-business policies that would be necessary to unleash a US-style equity boom. Macron’s slide in the French election proves the point. The votes are just not there.

To read my piece and for exclusive access to the Unhedged pages, follow this link.

Meanwhile, in their essay for Chartbook Robert Armstrong and Ethan Wu give a rather more upbeat assessment of Europe’s possible future.

It has been a privilege to work with them the last three weeks. I hope we do it again. In the meantime, enjoy!

****

Europe (to run in chartbook)

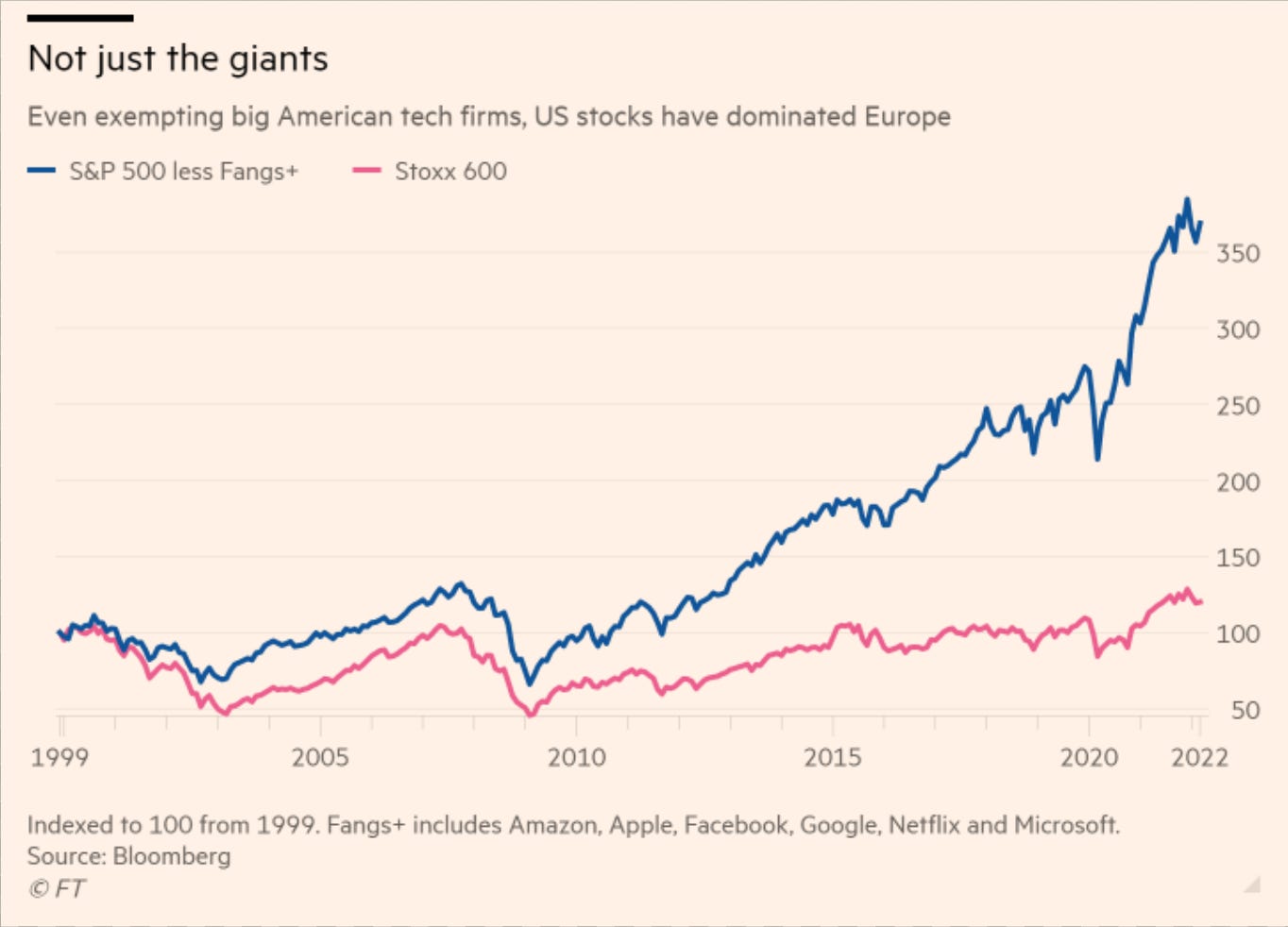

When markets people like us think about Europe, they tend to think about charts like this, which shows the relative performance of US and European stock indices (we have excluded the global tech giants that have led the US market, to make the comparison more representative):

For decades Wall Street strategists have been looking at charts like this and writing up investor pitches, arguing that the European gap with US markets must close, and next year -- whatever that year was -- was the year it would start to happen. Investors who acted on these arguments regretted it.

Excluding the big tech stocks, the price/earnings ratios of the S&P 500 and Stoxx 600 have hovered close together over most of the past two decades, differing on average by just 10 per cent. So US equities’ outperformance is not about inflated valuations, but rather about superior earnings growth at US companies. And this, in turn, must in part reflect better fundamentals of the US economy.

Here is total factor productivity growth, showing how peripheral countries have dragged on Europe, while even in northern Europe the gap with the US has persisted:

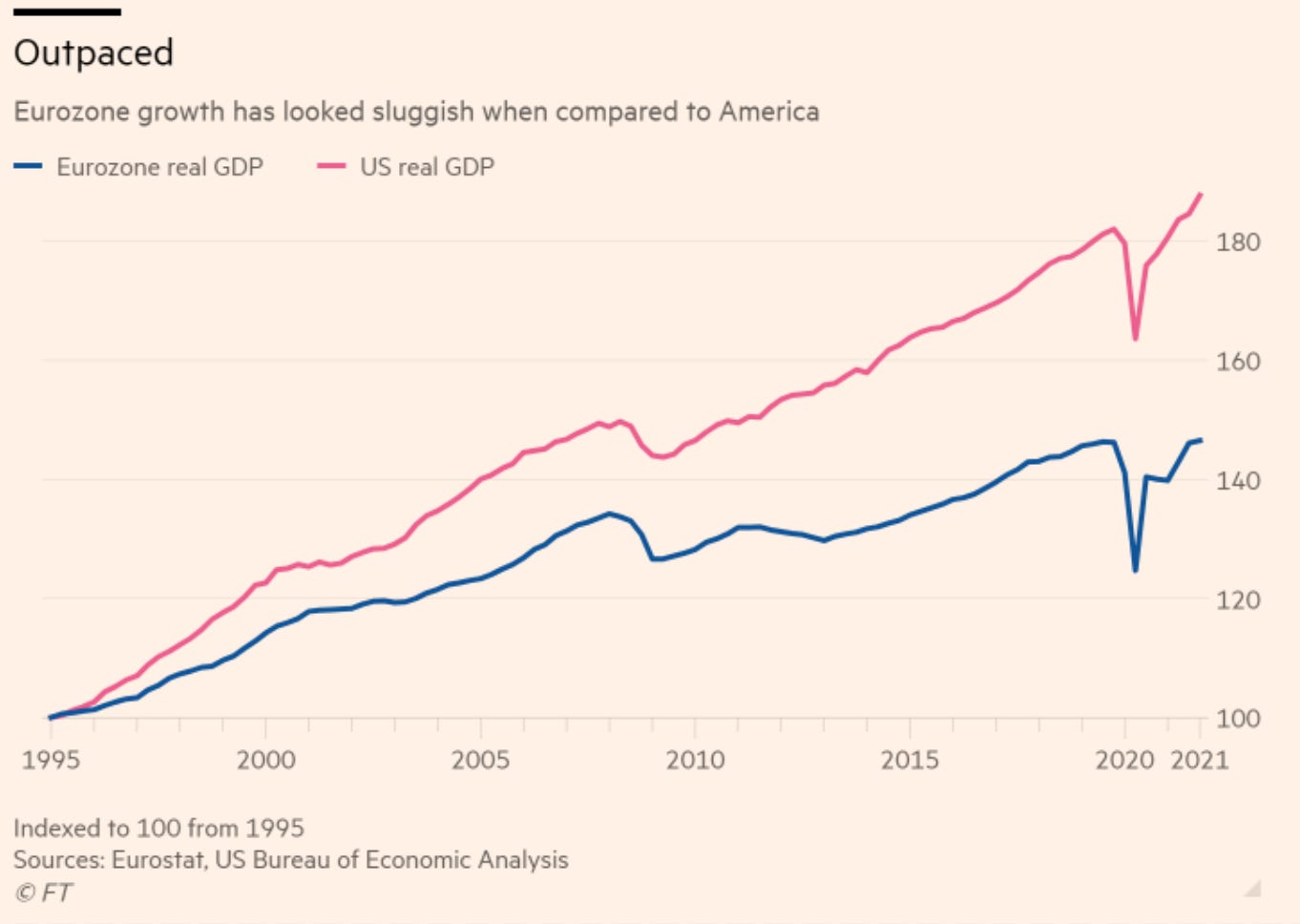

Europe’s economy has also seemed less nimble than America’s in times of crisis. Despite originating in the US, the 2008 financial crisis hit European output harder, followed by the added growth punch of the sovereign-debt crisis. During the height of the pandemic, startup creation in the US boomed 23 per cent while slowing or contracting across Europe, thanks in part to America’s more generous fiscal support. Pair fragility with weaker core growth and you get charts like this:

Despite the previous false dawns and dashed hopes, there is a case to be made that now is the moment that Europe turns a corner on growth and productivity, driven by two most unlikely catalysts: Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The twin crises have brought forth a unified European fiscal and political response, starting with the EU’s €800bn pandemic recovery investment fund. Already there is discussion among European officials about making the recovery fund permanent, and using the proceeds to meet the challenges revealed by Russia’s aggression. This is paired with recognition by national leaders (even German ones!) that more needs to be invested in the energy transition and in defence.

In sum, the hope is that the twin crises spur public investment in a region that has struggled with weak demand, and that these investments have private-investment multiplier effects which will meaningfully impact productivity in the long run.

Our FT colleague Martin Sandbu (who has forgotten more about Europe’s economy than either of us will ever know) points out that Europe’s strong fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic has led to a strong recovery. “In the pandemic, panic forced European leaders to drop their bad fiscal and monetary habits, and it worked -- the danger now is that they backslide.”

Laurence Boone, chief economist at the OECD, told us she sees reason for hope. “What is encouraging is there was this collective response to the war, after the unified response to Covid. It’s not just a one-off.” She sees four targets for a pan-European investment program, some of which could be funded by a central fiscal mechanism: energy transition, food security, digital security, and defence.

She also makes the important point that fiscal policy is only part of the reason that Europe has under-invested and under-grown relative to the US. Attempting fiscal consolidation too early in the recovery from the great financial crisis was a mistake. But there are also non-fiscal issues, notably the fact that Europe is still not really a single market. Capital markets and digital markets regulation remain splintered, for example, which is a heavy drag on productivity. Investment must go hand in hand with unifying regulatory regimes. Researchers have found that membership in the single market boosts trade and turbocharges foreign direct investment, as much as 85 per cent by one estimate. Deeper integration could bring similar benefits.

As Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein argue in their Trade Wars Are Class Wars, Germany’s reliance on foreign demand to absorb its exports has become a broader problem for European growth. Without reliable domestic demand like in America, business profits are exposed to greater competition and external fluctuations in demand. Here, Europe warming up to more government investment looks promising. Less austere budgets have a redistributive effect that could help rebalance Europe toward consumption.

But for all the momentum towards an investing, unified, rebalanced Europe, there is another trend pushing in another direction. Populist nationalism is resurgent as most recently demonstrated by Marine Le Pen’s surge in France’s presidential race. Markets have taken notice. Jonas Goltermann of Capital Economics points out that over the last week, the yield spread between French and German 10-year bonds has widened by 10 basis points. He sums up neatly:

The spread between French (as well as Italian and Spanish) yields and German ones have been widening for several months. As we discussed here, we think that mainly reflects the ECB’s intention to tighten monetary policy and its muddled message around how, and to what extent, it plans to support “periphery” bond markets in future…But over the past few days, the yields of French bonds have risen by more than those of Spanish ones, and almost as much as Italian ones. In previous episodes of ECB-driven spread widening, French yields rose by less…In addition, the share prices of the major French banks have fallen sharply over the past week (and by significantly more than those of other EU banks). So, “Le Pen risk” appears to be making a comeback

Here is his chart of the spread:

Remember it is the wobbly peripheral countries that have dragged on the region’s productivity, and which stand to benefit the most from investment, unity, and reform. Populism would leave them isolated and paying more to make the investments they need.

Inconveniently, the political window for structural change in Europe has opened just as inflation is spiking. Some sort of EU Recovery Fund 2.0 could worsen the problem — or, at the very least, hand opponents of joint European spending a powerful line of argument.

Europe faces non-political headwinds, too. The biggest and most stubborn is its ageing workforce, which puts a cap on domestic demand. That forces the continent's exporters to seek markets outside Europe, Claus Vistesen of Pantheon Macro told us, likely limiting much economic rebalancing toward domestic consumption.

For these and other reasons, transformation in Europe has always been slow, painful, or both. But greater fiscal union, higher investment and a more balanced economy are the way for Europe to close the gap with the US, and finally reward investors for betting on the continent.The twin crises of pandemic and war have opened the door to substantial change.

I think that a large part of the difference is cultural. As a general rule, Europeans are poorer and more frugal. The Germans are culturally predisposed to be savers. France has traditionally been less industrial than Germany, and an agricultural economy is generally regarded as being cash poor. Public ownership of business corporations lags behind the United States. In Europe, corporations are generally family businesses passed on from generation to generation, the corporation operating as a carapace, and without any meaningful existence of its own apart from the controlling family. Europe is typically more class-bound, and whatever inroads the working class makes it into the middle class are most frequently done as state enterprises, i.e., transportation systems, social insurance systems, postal savings systems, telecommunications, and the like. American-style go-for-broke capitalism is looked upon with fear and suspicion. European investments tend to be much more conservative than their American counterparts, and consequentially, they are less scalable.

The charts and graphs do not differentiate between productive investments and frivolities. American investors will bet on anything that looks like it might make some money, at least in the short run; and in America, the short run seems to be the predominant horizon. America does not have the 2000 year history of Europe, and Americans build for resale. Consequently, money moves through the American economy at a higher velocity and cyclic rate than it does in Europe. Americans are attracted to every bright shiny object that comes along, as Europeans look on with envy. Americans go broke more often, but the motto of American businesses is and has always been, 'Fortune favors the bold'.

The upshot is, and has always been, that bankruptcy has never had the stigma in America that has in Europe, where insolvency has traditionally taken on much more of a stigma of moral failure. America had the lure of an open continent to settle and develop, where land and resources were cheap, or any group of men who could cobble together enough money could set up a business that could survive the ups and downs of the business cycle. In this regard, Europe has been less forgiving of economic failure. No doubt, Americans waste more money than Europeans, but even wasted money cycles through an economy with the same velocity that well spent money does; and the more money that is spent, and invested for others to spend, the more likely it will be that, mirabile dictu, things that were unimaginable suddenly become the objects of investment and greater wealth. The American economy is more diverse; the taste makers are fewer and less influential. That diversity of taste and variety of experience is the stuff of life itself, with some succeeding, some surviving, and others failing. But the American economy is not bound by tradition, or a top-down hierarchy of what a suitable investment should look like. American entrepreneurs are known for being outrageously bold, gauche, and having a knack for making money, lots of it, which they then proceed to lose on other ventures that were equally as unlikely to succeed as those that actually made money.

Labor's share of GDP hasn't decreased at the same rate in Europe as it has in the US. (Which is the flip side of more of US GDP going to corporate profits that boost share prices.) Neither have European-listed companies received the same 2017 cut in the corporate tax rate that US-listed companies have.