Chartbook Newsletter # 6

Britain on the Brexit Brink

On the brink of Brexit (no deal or not), I’m still struggling to make sense of what has happened since 2016.

The best historically informed take, is this brilliant piece for the Guardian by my good friend David Edgerton.

Edgerton not only grasps the significance of the dissociation between the Tory party and what is left of British business, he explains it historically. The key is the dissolution of the national economy paradigm since the 1970s.

Edgerton followed it up with a second excellent piece myth-busting the legends of British innovation and the entrepreneurial state. This is crucial because in the endless Brexit negotiations, the really key issue is the question of state aid rules, industrial policy and ensuring a level playing field between UK and EU. What explains the British preoccupation with state-aid is the fantasy that if freed from EU constraints the UK government will be able to unleash a dynamo of national innovation long stifled by Europe. As Edgerton argues, if history is any guide, it is a gamble at long odds.

The second big issue, is how any deal on trade will be enforced and how conflicts will be arbitrated. The tougher the underlying agreement, the less need there is for a strong enforcement and arbitration mechanism. The weaker the agreement, the stronger the mechanism needs to be.

Fundamentally, what are at issue are radically different visions of the future. Following the break, the EU envisions broadly parallel development between the EU and the UK under the terms of a stable agreement. By contrast, the Brexiteers intend to steer an increasingly divergent course from the EU (Where to? Who knows? ). For the British side, therefore, the agreement is not a charter for parallel development, but a menu of the penalties they will have to pay to steer that divergent course and, of course, they want to keep the terms as opaque and the price as low as possible. For the same reason the trust between the two sides is close to zero. This explainer by @pmdfoster in the FT is excellent.

Apart from the trade deal and the rules of enforcement the third “major” issue at stake is fisheries. I kid you not. An industry which on both sides accounts for 0.1% of GDP has become a major test of the question of sovereignty and a trial of strength in particular for French influence over the negotiations.

The UK still likes to think of itself as a “maritime” nation, but the fishing fleet has been in decline for decades.

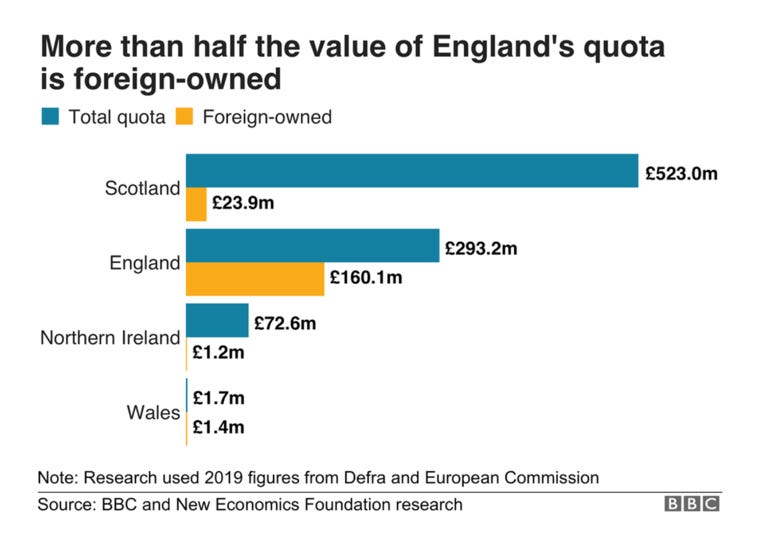

When prices for fishing quotas declined in the 1990s, British captains sold off their share to European competitors who now dominate fishing in British waters. Its a sensitive subject. Note the BBC’s description of the quotas as “foreign-owned” rather than as “British-sold”!

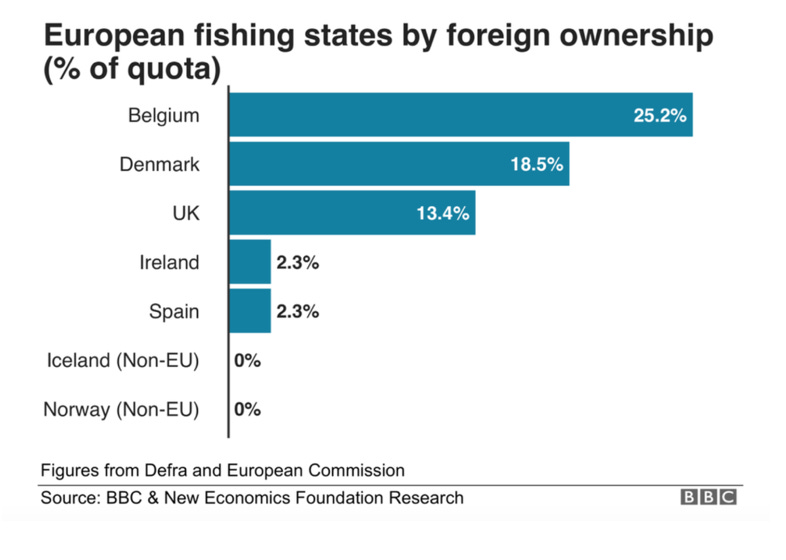

Nor was this sale of quotas peculiar to the British. The share of Belgian and Danish fisheries owned by other fleets is larger.

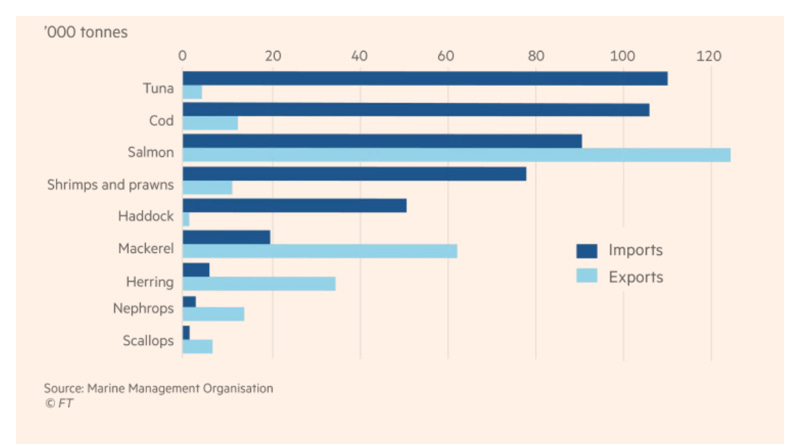

One problem is that for all the “spectacular maritime wealth” of which the British government likes to boast, the Brits don’t actually like to eat the fish caught in their own waters. They prefer fish like tuna that are imported from outside UK waters.

The entire fishing and fish processing industry in the UK employs c. 24,000 people, most of them working on fish, 80 percent of which is exported back to the EU.

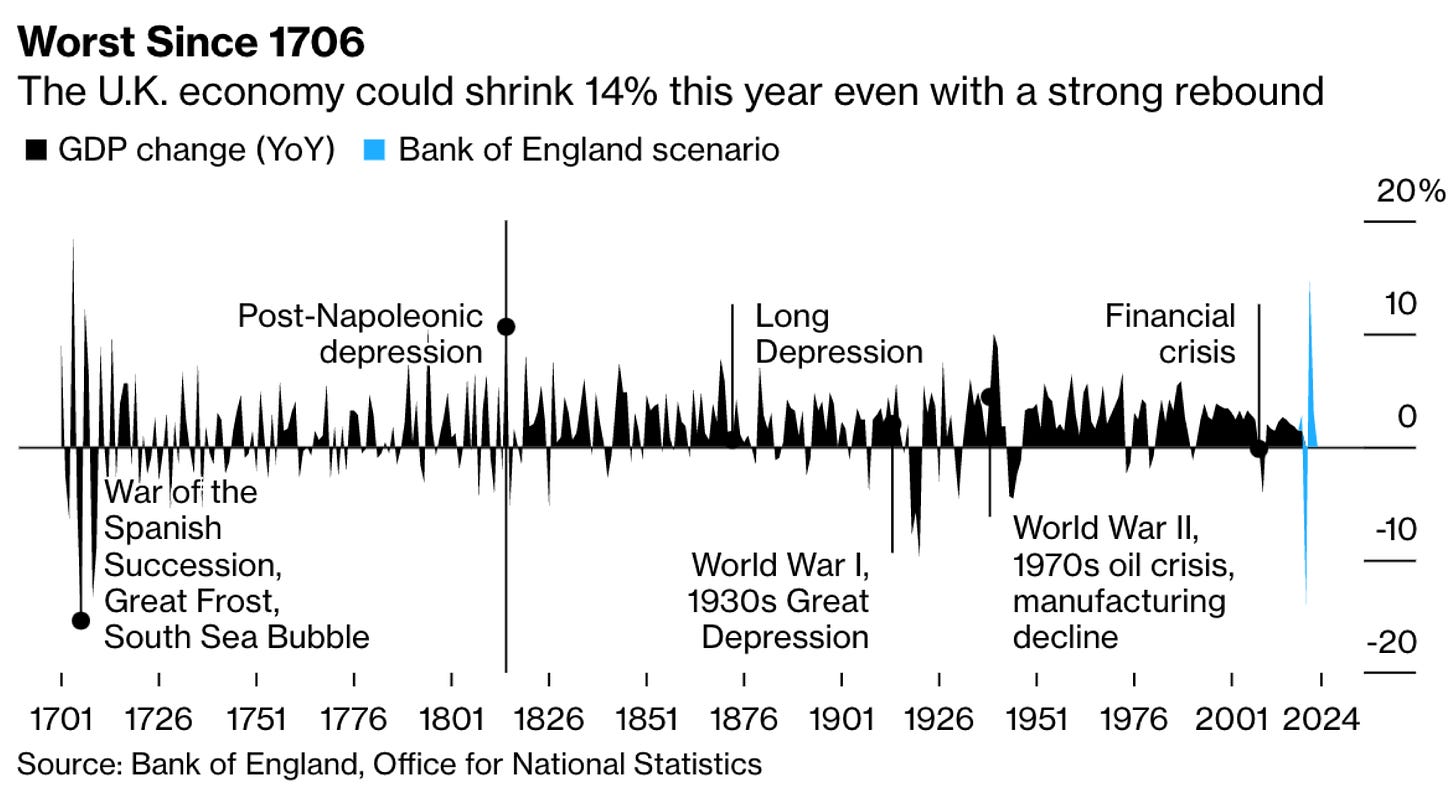

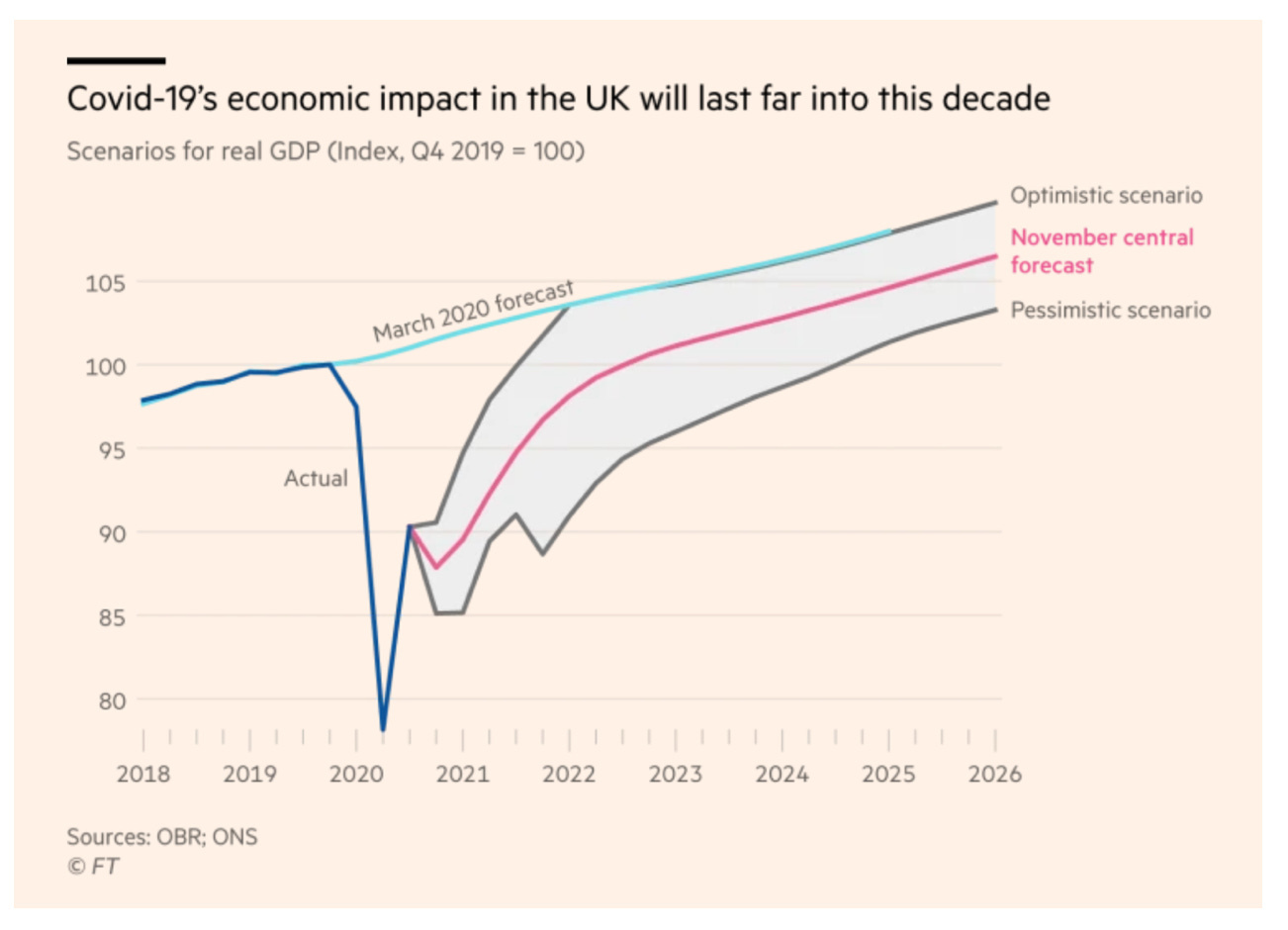

It is an extraordinary and absurd situation that an industry of this scale should have acquired the totemic significance that it has . Meanwhile, the combination of corona and Brexit threatens to inflict on the UK a truly historic economic shock. By the calculations of the Bank of England, it is the worst in 300 years, that is as far back as the early 1700s, at the time of all out war against Louis XIV (aka “Sun King” master of Versailles).

1707 was as bad as it was because of the disastrous climatic disturbances of the period, culminating in the legendary Great Frost of 1710.

As @ChrisGiles_ puts it in the FT the UK faces an economic emergency:

"Not since the second world war has a UK chancellor had to come to the House of Commons and announce such a large downgrade to the outlook for Britain’s economy and public finances.”

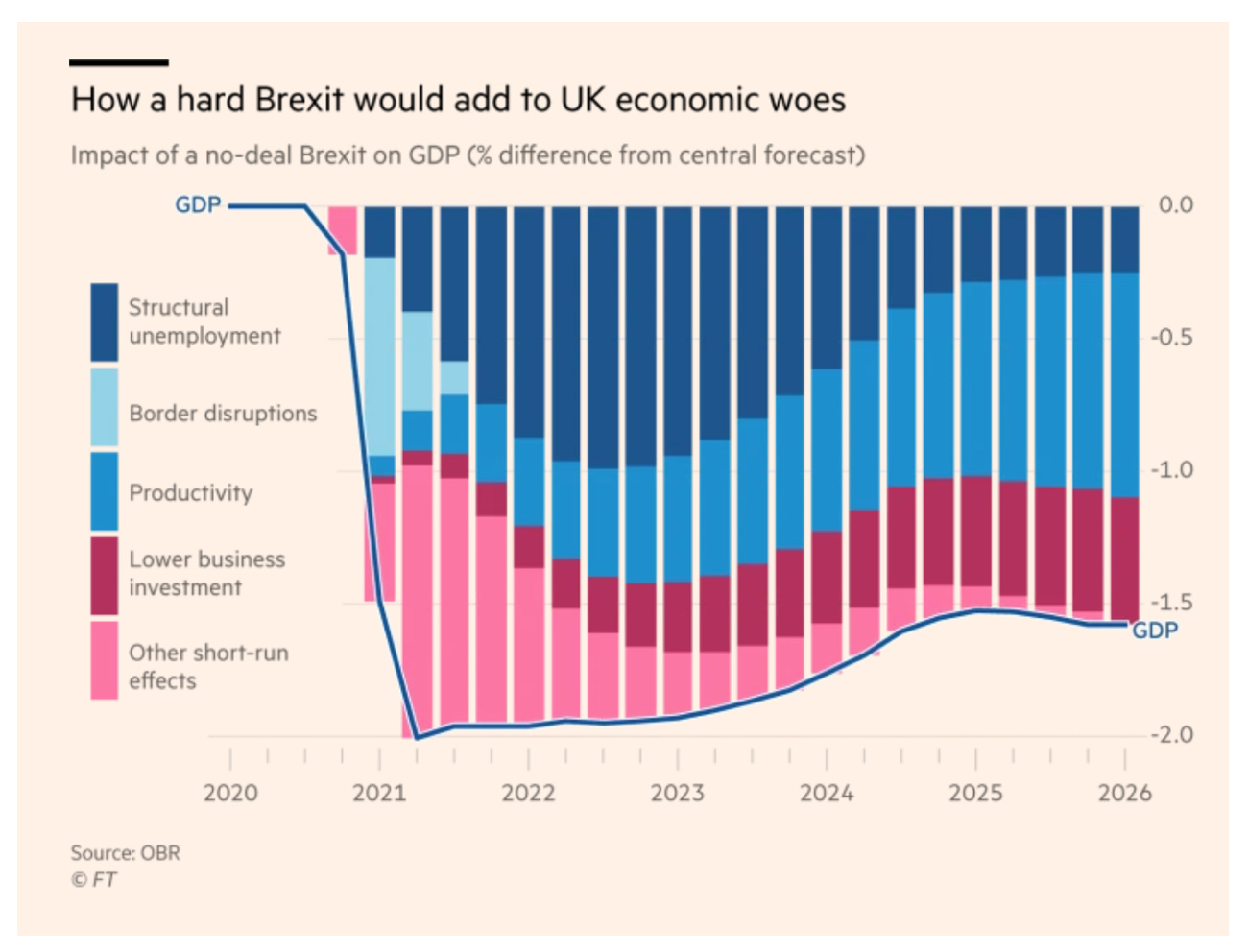

The impact of Brexit will compound that with further shocks both in the short and long-term.

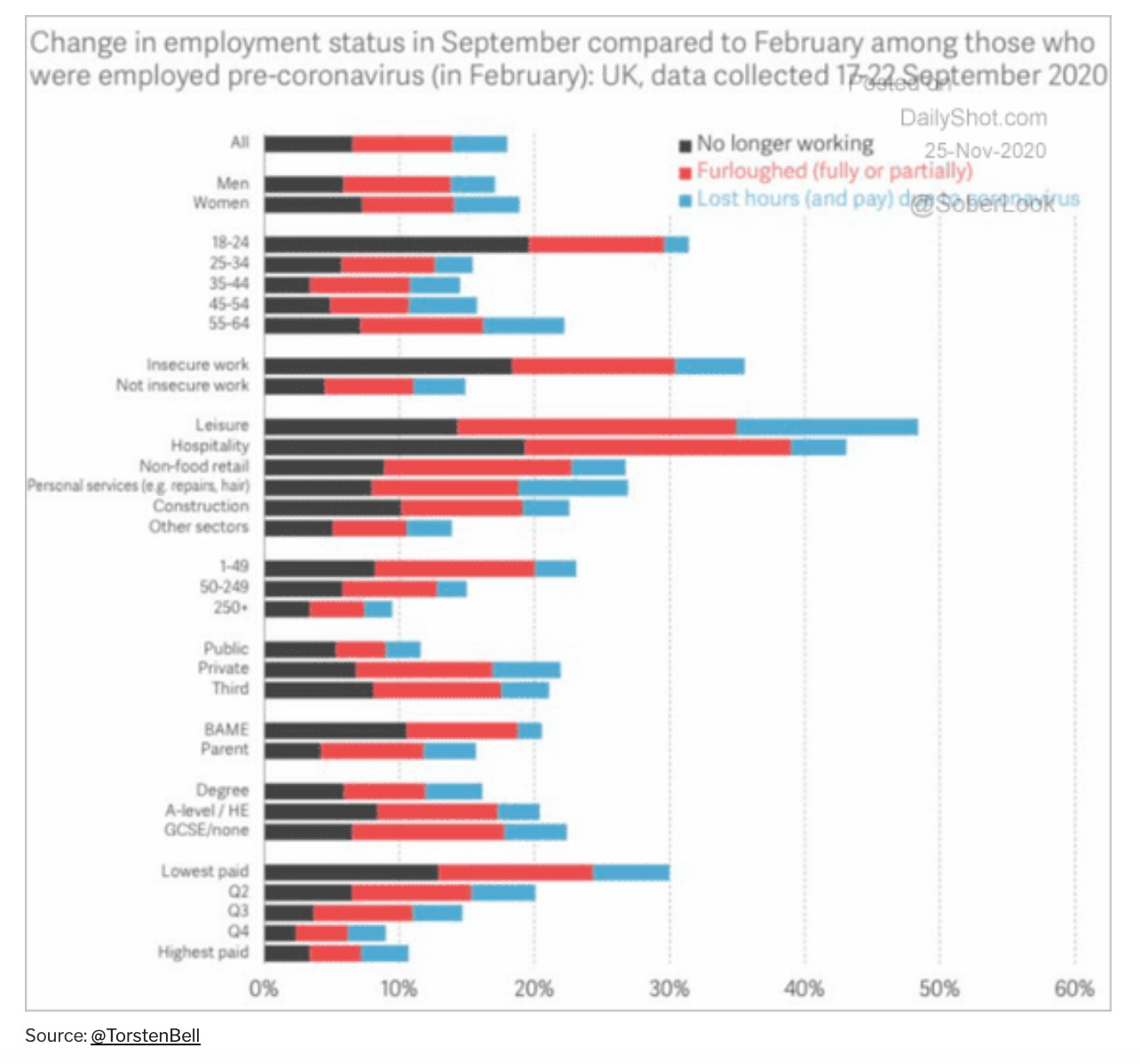

And the impact of the combined shocks of 2020 is worst on the youngest, least well-educated and worst paid, as this chart by @TorstenBell via @SoberLook makes clear:

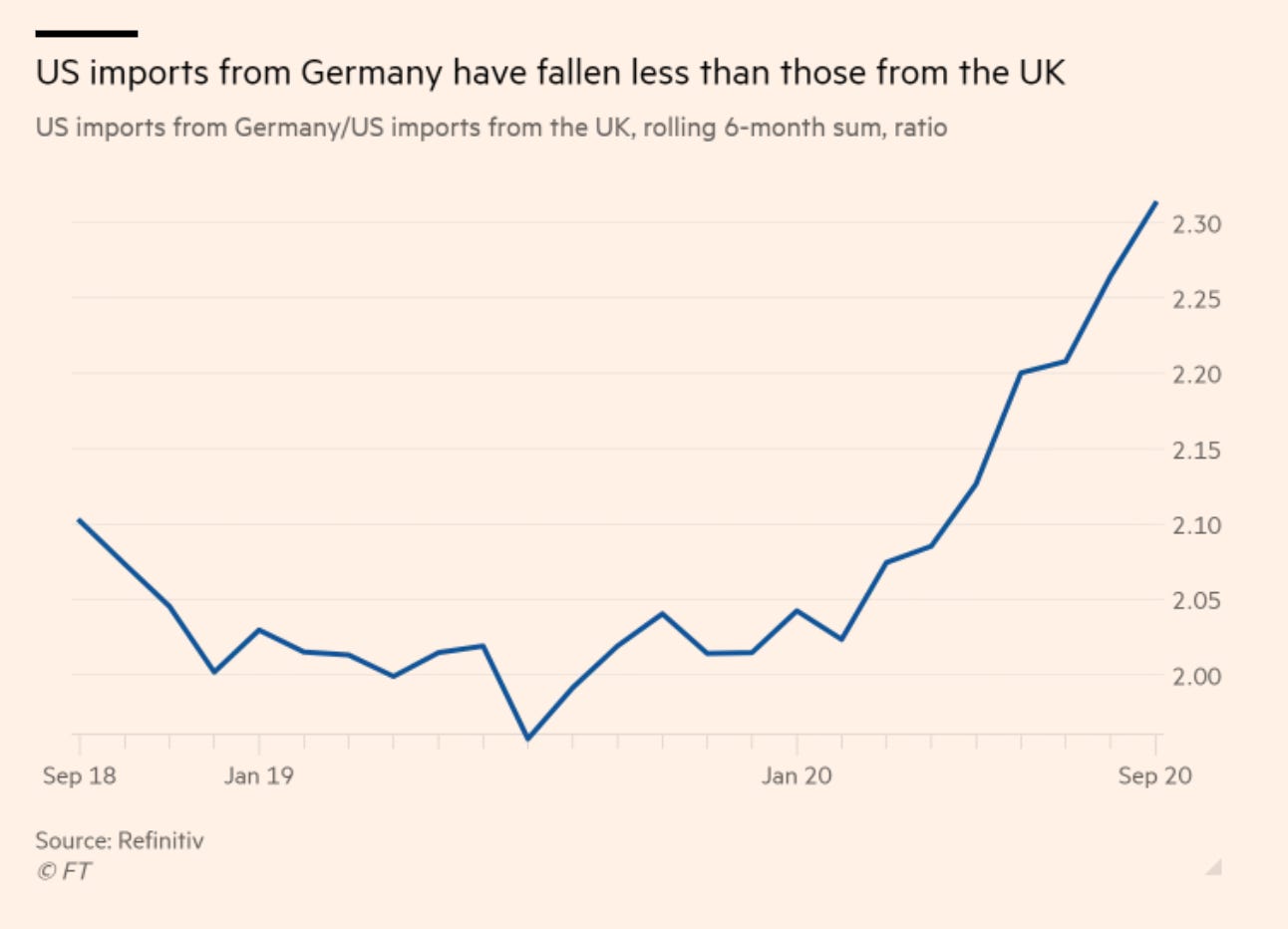

The future that Brexit supposedly holds out is one in which the UK emerges as stronger, more competitive global trader. All the data from this year suggest how far that is from reality, at least at this current moment.

A piece by @valentinaromei in the FT offers a sobering round up of recent trade data.

Global Britain? In 6 months to Oct, value of goods imported into China from UK fell 18 % compared with 2019, while it rose 1.1 % for goods coming from Germany — and by more than 5 % for goods produced by Italian manufacturers. @valentinaromei

In 2020 US imports from both Germany and UK contracted, but UK goods were hit far harder -> German/UK ratio surged. @valentinaromei

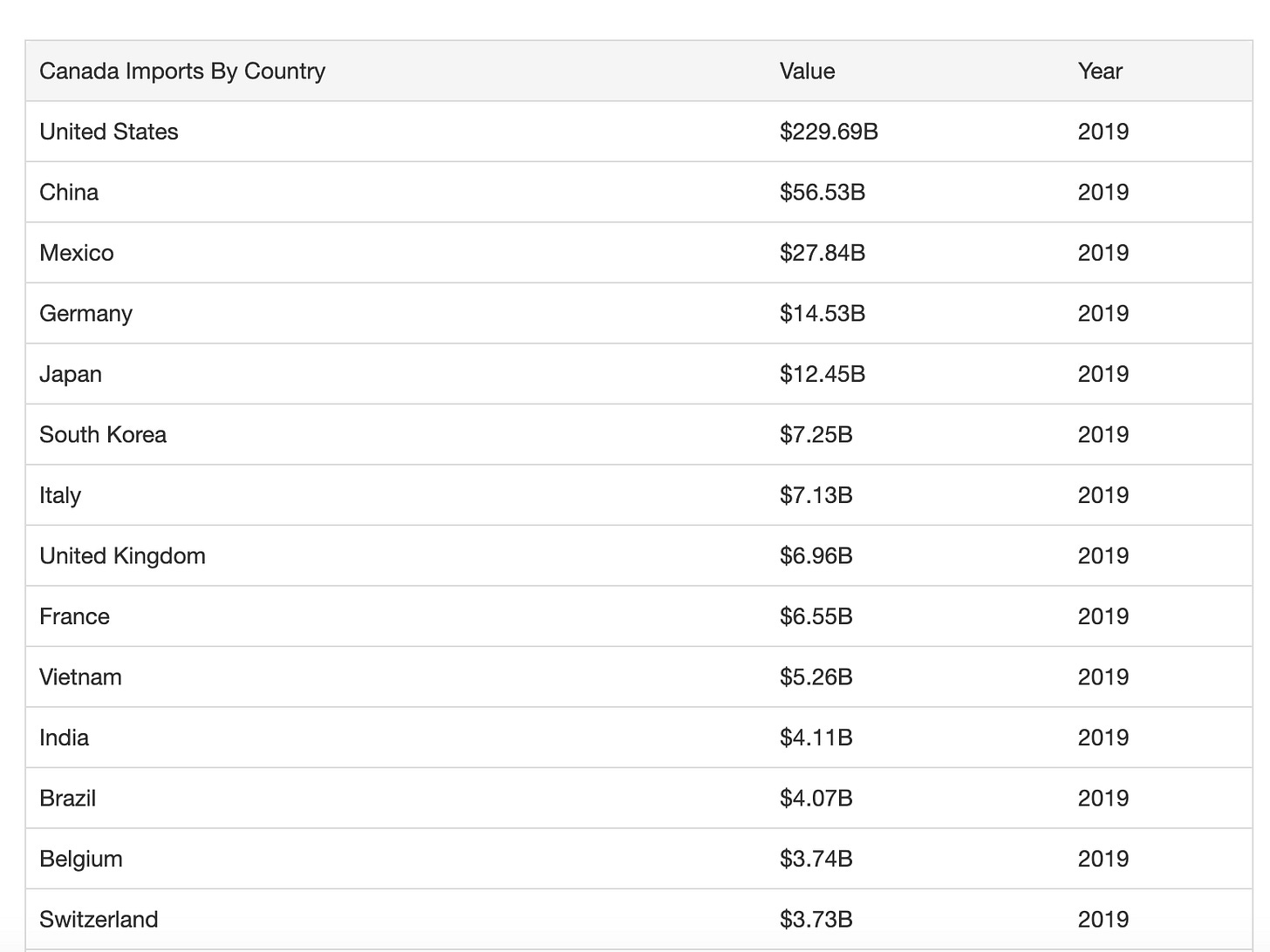

Meanwhile, the "White Commonwealth” bulks large in the imagination of Brexit. But on the actual prospects in that direction, data on Canada given a realistic impression. It shouldn’t be a surprise that Germany exported twice as much to Canada as the UK. But, I was struck by fact that Italy pipped the UK to #7 spot!

Source: Trading Economics

What are the prospects for a deal?

At this point, time is truly running out. On the European side, the most significant development of recent days is that the EU member states are beginning to put the Commission under pressure to prepare a Plan B for the event of no-deal. Whereas London seems to want to engage in brinkmanship, they want a more rational way forward. Draw your own conclusions.

PS Chartbook Newsletter will be returning to the March 2020 retrospective at the weekend. Prompted by the last post, I have received a bunch of interesting input in recent days from a variety of sources. Much to mull over.

Interesting, informative content, well written and presented.