Chartbook Newsletter # 12

No Room for Complacency in the Euro Area in 2021

Wishing you a very belated Happy New Year.

With just three weeks to go before submission of the manuscript for Shutdown - out in September - things are getting pretty intense.

But, life goes on. Term has started. I have a regular column to do for Social Europe and I’m looking forward to giving one of my monthly talks for Conley & Silvers on Monday night.

So, I thought I would take a break from the grind on the book, to do a newsletter on the outlook for the Euro Area.

Btw: If you would like to join the Conley&Silvers talk, it will be on Monday 25 January 8 pm New York Time.

I often accompany my wife’s boutique educational travel company Conley & Silvers as a lecturer, and during COVID times, we've been staying in touch with our community via zoom. If you enjoy zoom talks you are most welcome to join us. To join my talk Go to the Conley & Silvers website, then find my next talk on the calendar (25 January), click on that talk and book your slot. Use the code WINTERESCAPE at checkout to claim this, or any other, complimentary talk.

There are all sorts of wonderful lectures on the C&S platform. So, if you enjoy travel, art, culture etc, you might enjoy checking out the full C&S calendar. Note: If you sign up for the lecture you will get the recording of it regardless if you actually are able to attend in person.

The Bane of Euro-Complacency

I’m a passionate Europhile.

I grew up in West Germany, English, but bilingual.

Not one. Nor the other -> hence European.

Brexit, one of the worst days in my life.

At Columbia, I direct the European Institute.

I write for Social Europe ….

…. and, for all those reasons, because of those commitments, there are few things that get me more riled up than Euro-complacency and especially the kind that is twinned with Schadenfreude about America.

For obvious reasons, there has been a fair amount of this kind of Euro-complacency recently. You can’t do a panel with senior EU folks, or European think tankers without hearing that “we handled COVID better than the Americans” (sic). The narcissism of small differences is one of the curses of the trans-Atlantic relationship.

Added to which, there is now a lot of self-congratulation on the theme of European fiscal policy.

In July, the Europeans did a package deal to combine the usual 1 trillion euro, 7-year Multiannual Budget Framework with the 750 bn Euro Recovery package known as Next Generation EU. The Next Gen EU program will be financed through EU-level borrowing and half of it will be disbursed as grants.

This was a remarkable breakthrough brokered by the French and Germans. It also puts some flesh on the bones of the EU’s Green Deal on climate. For more, check out this Foreign Policy piece.

Then, in December, in another round of high-wire negotiation, Berlin also overcame last ditch objections from Hungary and Poland over rule of law conditionality and the run down of Poland’s coal industry.

It was a real achievement of European diplomacy. Perhaps Angela Merkel’s last hurrah as the de facto leader of Europe.

The Germans and Dutch will insist it was a one-off response to corona. Let us hope they are wrong. Let us hope, that the normal EU ratchet operates and that it becomes a model for many more initiatives of a similar kind.

But, as impressive as it is as a political and diplomatic achievement, the question that is most urgent in 2021 is simply this: Is it big enough?

Big Enough?

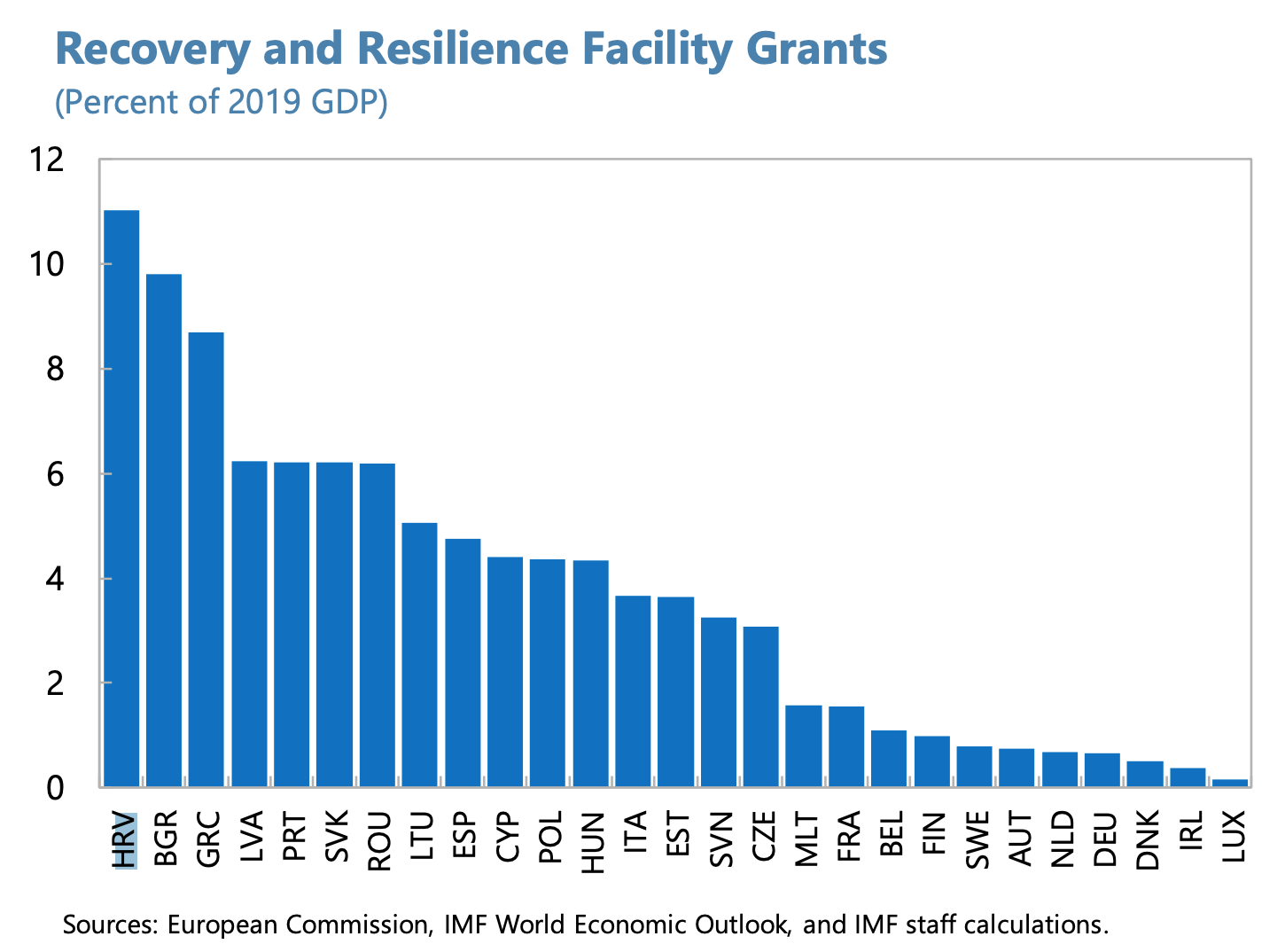

The sums of money being distributed from the Recovery Fund, are non-trivial, especially for Eastern European recipients, but also for Spain and Italy.

The funds are supposed to be heavily directed towards the new investment priorities of the EU - green, digital etc.

There are serious questions about whether all the governments can actually come up with programs to spend the money in a targeted way.

But beyond these “supply side” considerations, the question is simply whether the funds are adequate to offset the macroeconomic shock that Europe has suffered.

The 2020 shock

Speaking to EU officials you sometimes get the impression that they don’t appreciate quite how serious the hit to Europe’s economy has been.

Read the end of year reports by OECD, IMF and European Investment Bank on the Euro Area and it is NOT a pretty picture.

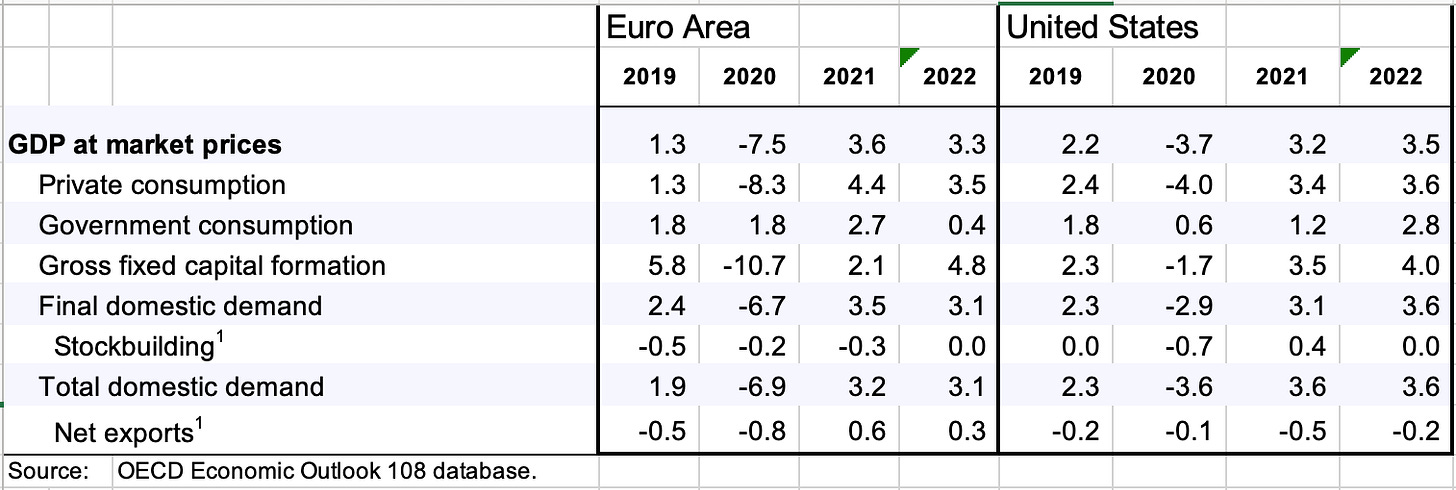

The OECD thinks Euro Area GDP declined by 7.5 percent in 2020, as against “only” 3.7 percent in the US.

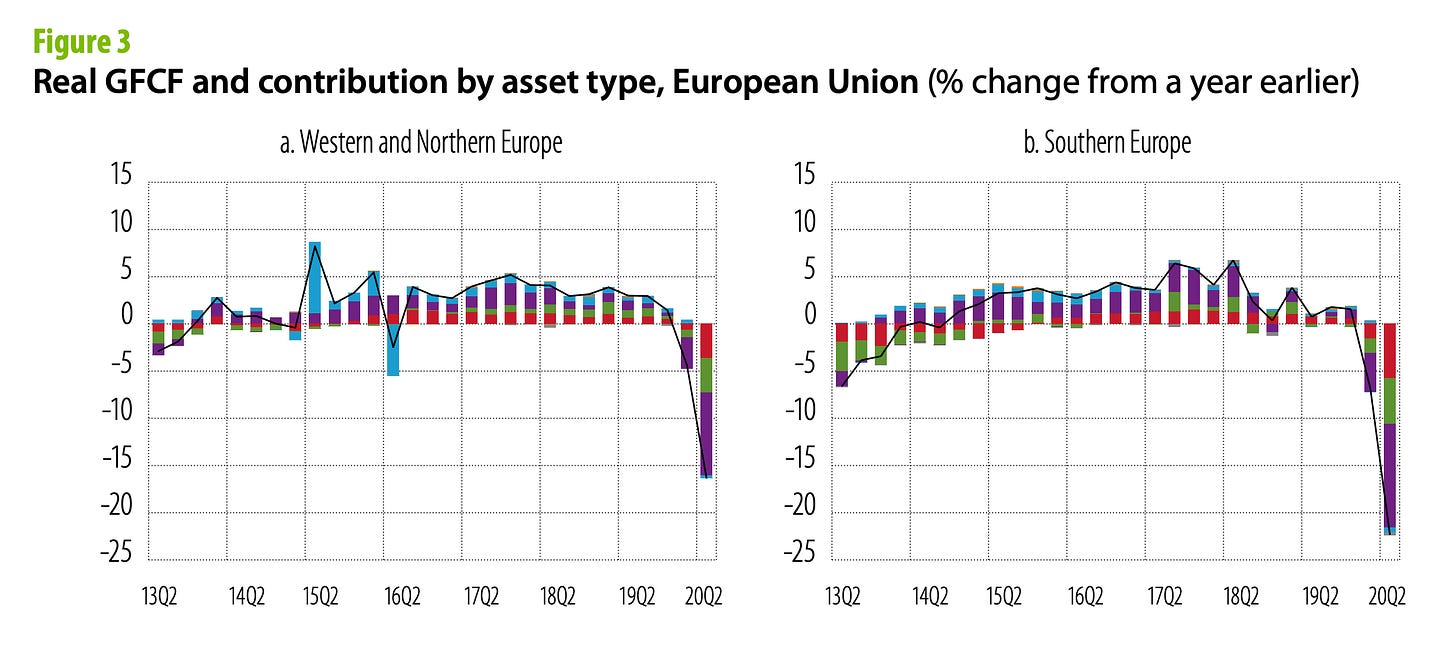

The collapse in Euro Area gross fixed capital formation ought to be particularly horrifying. Particularly so, because it is worst in Southern Europe.

Source: EIB

Slow Recovery

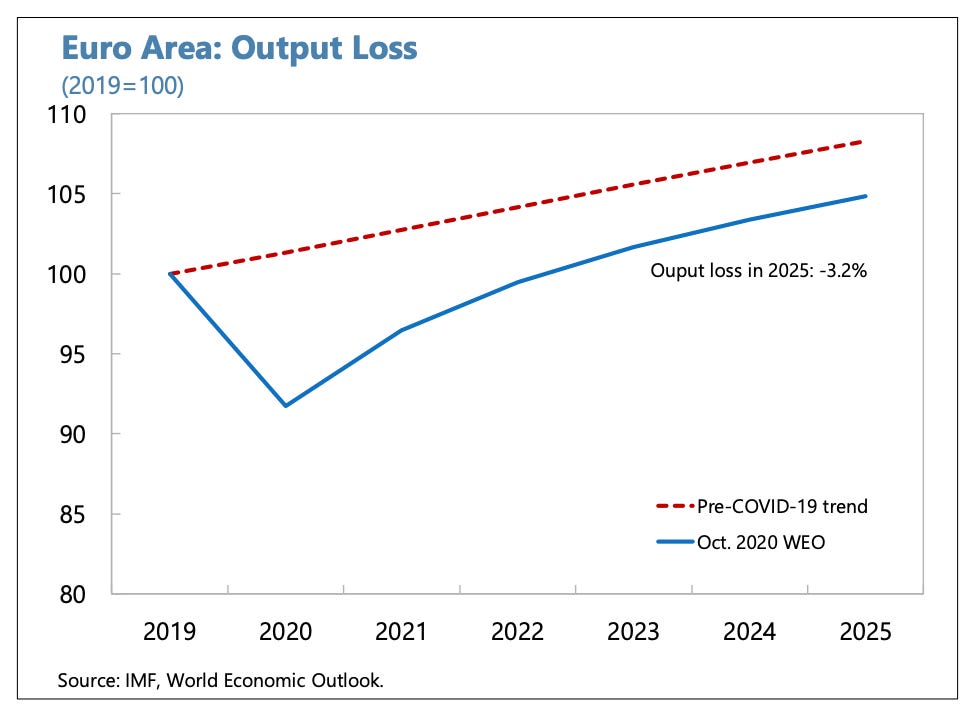

The projected recovery of the Euro Area is appallingly slow. Whilst the US is now looking forward to a rapid rebound in 2021, the Euro Area is not expected to recover to 2019 levels of output until the end of 2022. In 2025 Europe will still be far below the pre-corona trend.

And the recovery is expected to be patchy. Spain is still expected to be 3 percent down on its 2019 output at the end of 2022.

This is a scenario that ought to set off alarm bells in Brussels. Can anything be done?

Monetary Policy

The ECB is Europe’s only really powerful common economic policy agency. It has been pivotal since March 2020 in preventing the recurrence of a sovereign debt crisis in Europe. But that is a necessary not a sufficient condition for rapid recovery.

The ECB’s ability to affect the broader dynamic of the European economy is far less obvious.

The ECB’s mandate specifies price stability as its objective. It is supposed to keep inflation below 2 percent. Down to the 1990s that would have been a demanding task. But in recent decades the main problem has been not so much to prevent inflation as to avoid deflation. And that is the ECB’s current concern.

Inflation expectations give a further indication of just how lack luster is the outlook for the Euro Area.

The Euro is rising against the dollar in large part because investors fancy it as a hedge against the revival of inflation in the United States. Slow inflation and a strong euro mean slow growth for Europe.

Fiscal

If there is a policy answer - a big if perhaps - to Europe’s slow recovery, it must lie with fiscal policy.

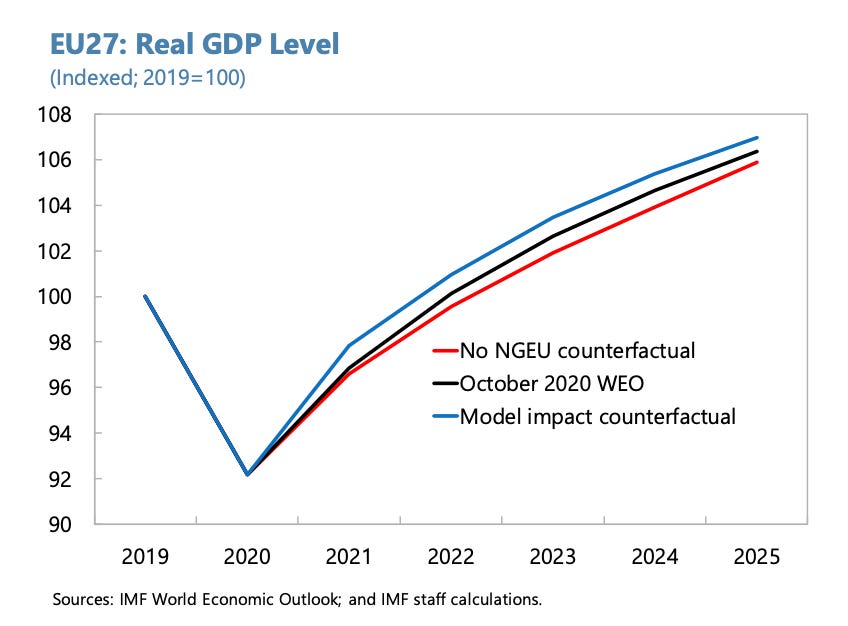

Next Generation EU is a good start. To see why it can only be a start look at the IMF’s annual report on the Euro Area. The brave economists at the Fund have attempted to estimate the impact of Next Gen Eu on the growth curve. Their base case is 0.75 % of GDP by 2025. The most optimistic model would credit it with raising output by 1.5% by 2025 GDP. That is not nothing. But it is half the expected gap

Estimating the size of the necessary fiscal boost is a tricky business. But, in 2020 the US delivered twice the discretionary fiscal stimulus to its economy that the Euro Area did and its GDP contraction was half that of the Euro Area.

Why not double the Next Gen EU package?

The politics of any such proposal are of course extremely difficult. But one should not be under any illusion about the alternatives. A Europe suffering from slow growth an increasing divergence cannot be politically or financially stable.

A Crisis Pending

I am not a Euro-pessimist. Europe has shown a remarkable capacity for muddling through. It is the best alternative open to its members. For good reason the majority of Europeans continue to support the EU and its key institutions. But how can this be a stable basis for Europe?

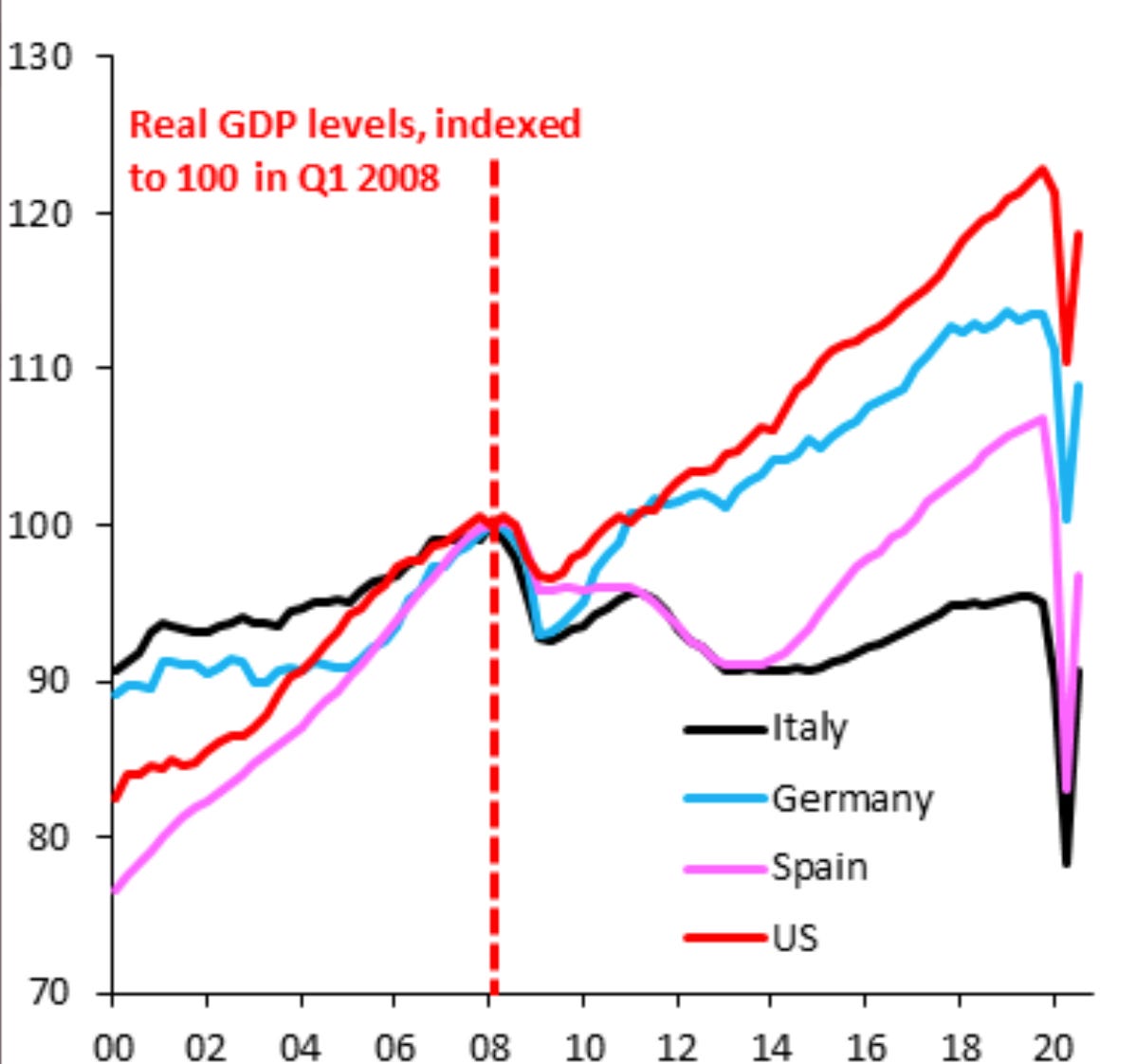

In Q3 2020, after a rebound from the worst of the corona shock, Italy’s GDP was ten percent below its level in Q1 2008, twelve years ago!

Thanks, as ever, to my twitter buddy and leader of the CANOO campaign, Robin Brooks, for this truly dramatic graph!

See you at the Conley & Silvers talk. Check out the Social Europe column on Monday!