In struggling to comprehend the multi-faceted global climate crisis, we need to distinguish two separate historical developments that are currently unfolding side by side.

One is the beginning of a comprehensive, though uneven process of technological change that will eventually transform a large part of the world’s energy systems. In a commonplace, though misleading shorthand we refer to this as the “energy transition”. This “transition” is driven by policy, technology and economic impulses. It was originally fired by climate concerns, but has now taken on a life of its own under the slogan of green industrial policy or green energy geopolitics.

The second trend, no less undeniable, is the escalating environmental disaster and the fact that the energy transition that is now underway is nowhere near large, fast or focused enough to deliver what was was originally promised, i.e. comprehensive decarbonization and climate stabilization.

In climate policy jargon, this disjuncture is commonly referred to as a “gap”.

Ahead of COP there were a number of “gap reports”. One that may be of particular interest to Chartbook reader was issued in November by the climate team of the IMF.

Over the last few years, the IMF has made climate into a prominent feature of its financial surveillance and at the same time it has also, itself, entered the climate policy arena. In October 2021, the IMF issued its Climate Change Strategy.

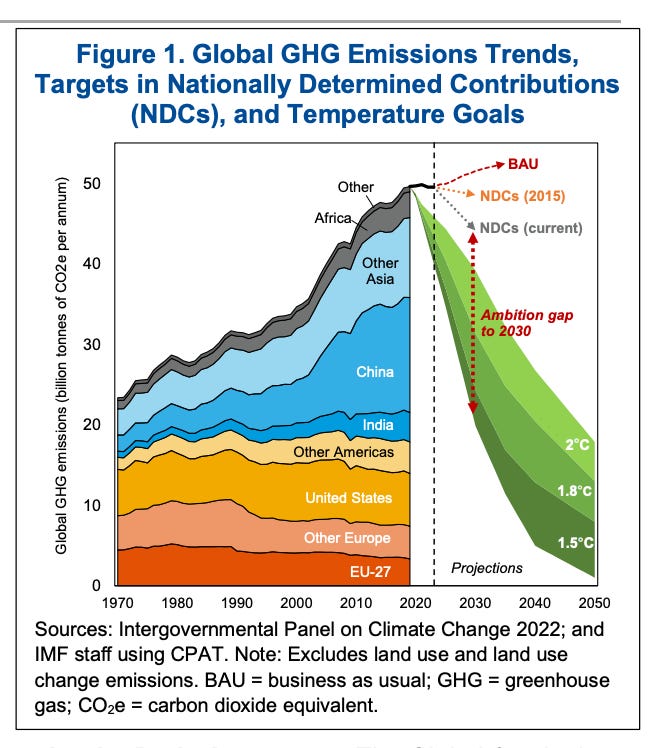

It is a moment for all hands on deck. As the IMF team show, despite the professed aims of the 2015 Paris Climate Accords, we are not on track. Current decarbonization policies fall far short of what would be necessary to give us a fighting chance of climate stabilization at between 1.5 and 2 degrees of warming.

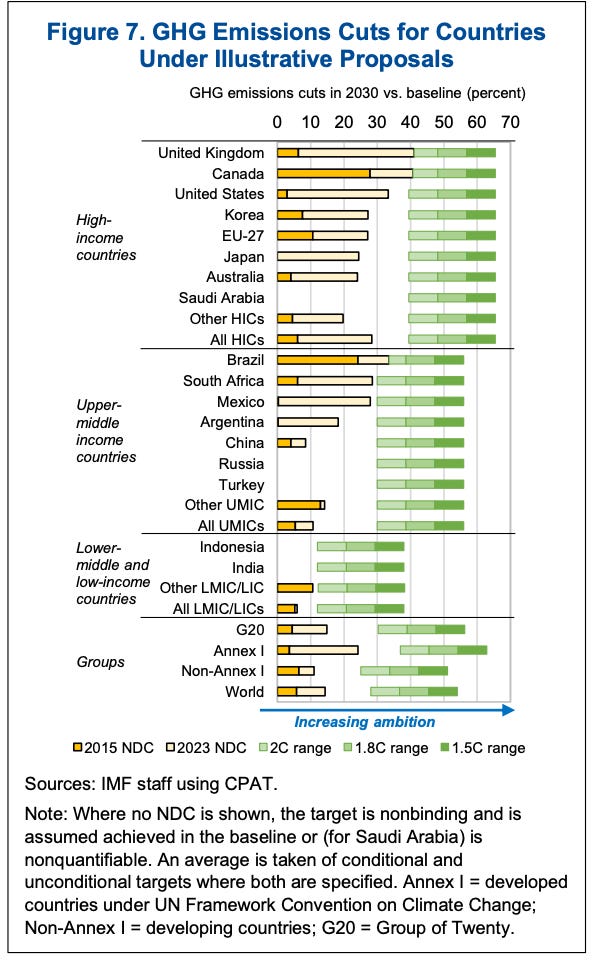

The first round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) announced following the Paris accords in 2015, were barely enough to dent the emissions curve. Successive rounds of climate policy have raised ambition, but current NDCs fall far short of the reduction we need to see.

This is the common conclusion of all “stock takes”. It is why, since the Glasgow meeting, the COP conferences have finally taken up the challenge of talking openly about ending the use of fossil fuels. It beggars belief, but since the mid 1990s the COPs have met year after year, whilst leaving this basic question unaddressed.

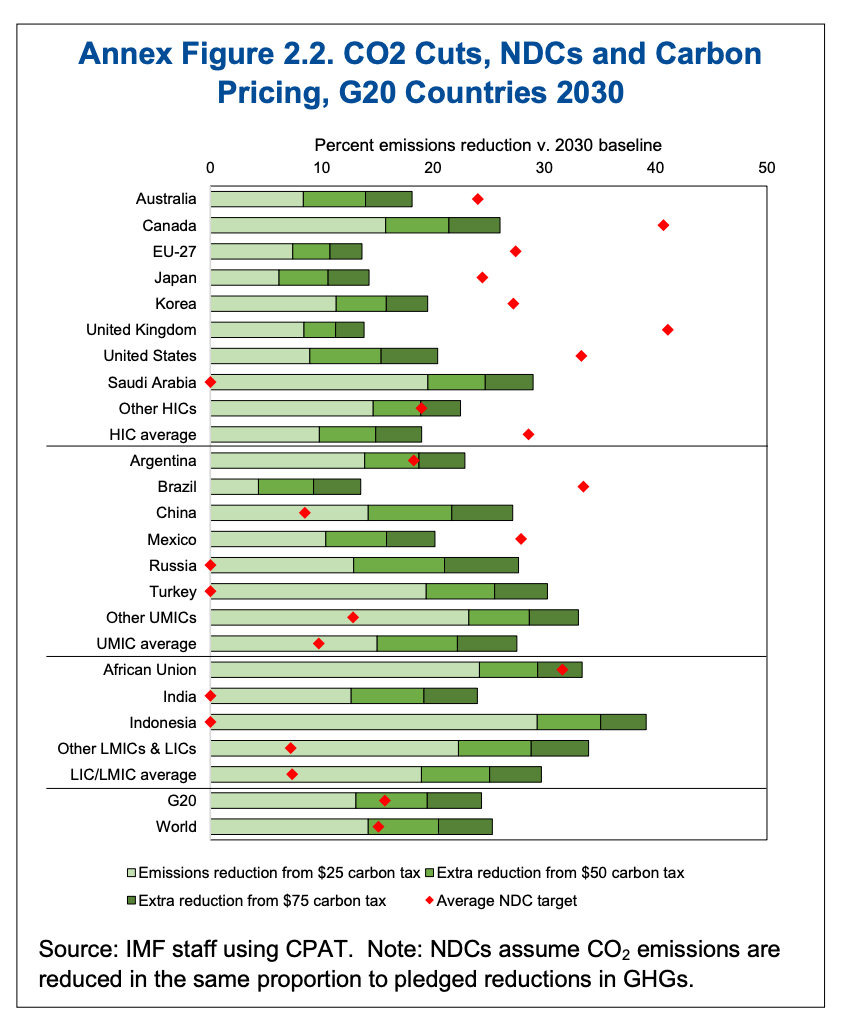

Apart from the general conclusion of inadequacy, the IMF’s gap report has two distinctive features. One is the Fund’s continued commitment to carbon pricing as the benchmark of decarbonization policy. This has long been the conventional answer given by economists to the challenge of decarbonization. And it is easy to see why. A high carbon price offers a general disincentive to pollution, it truly penalizes fossil fuel sectors, and at the same time creates a powerful incentive to investment in low-carbon technologies. A $75 carbon price would, at least according to the IMF, take most countries to within striking distance of their NDCs.

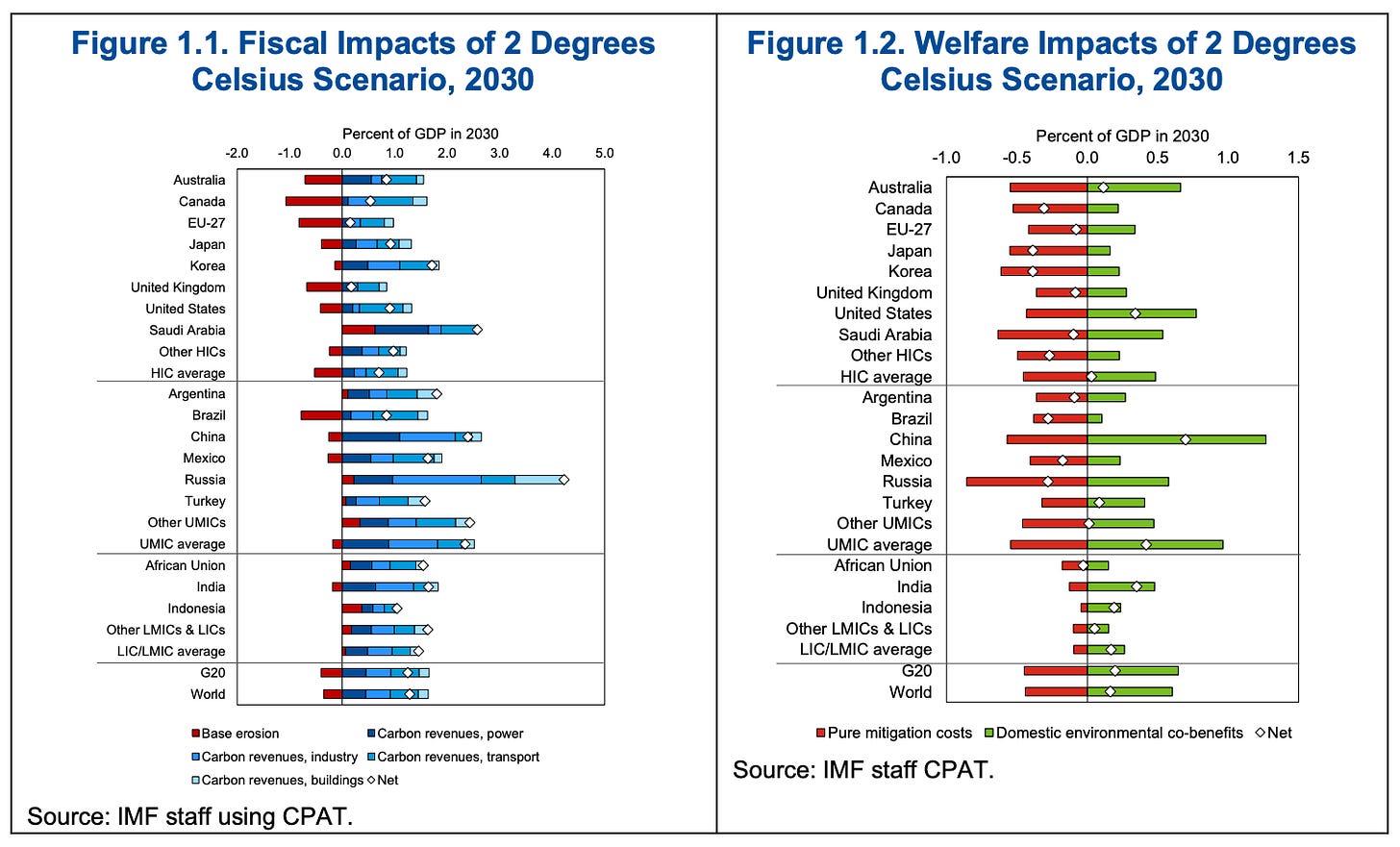

The carbon taxes would also generate a substantial flow of revenue, to the tune of perhaps 1-2 percent of gdp. This could then be redistributed to those groups hardest hit by the transition.

But, as compelling as the logic of carbon pricing is, according to the lights of mainstream economics, the politics says otherwise. Against the backdrop of America’s two failed efforts to introduce carbon pricing, under Clinton and Obama, and given the miserable performance of California’s carbon pricing system, it has become conventional, especially in the US, to doubt both the desirability and viability of carbon pricing as a general solution. It is undeniable that additional incentives and policies are necessary to generate the required investment and innovation. The Gilet Jaunes protests in France in 2018 serve as warning against excessive ambition when it comes to carbon taxes. A recent report by the Task Force on Climate, Development and the IMF - an expert group set up in October 2021 to monitor and assess the IMF’s climate efforts - has helpfully summarized the wide-ranging arguments for non-price policies.

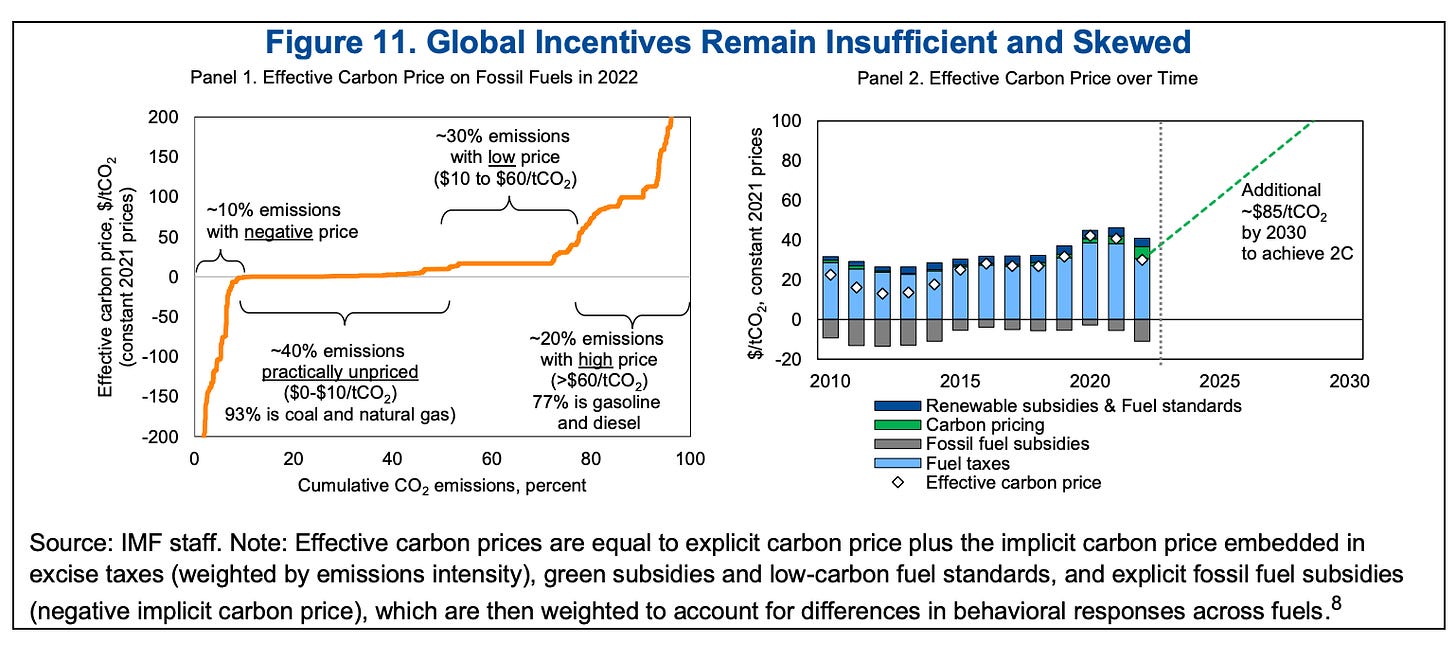

These criticisms of one-size fits all carbon pricing policies, are well taken. But to dismiss carbon pricing altogether is itself parochial. About half of global emissions have some price attached to them.

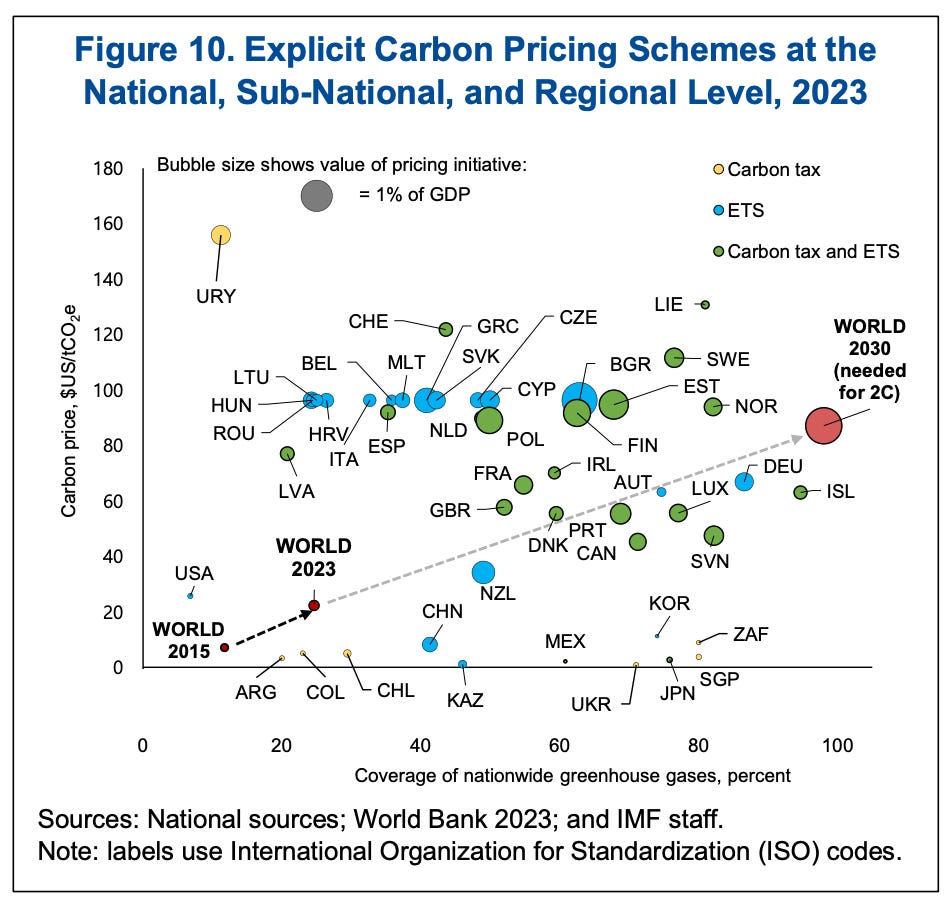

In the US, carbon pricing may be dead. But, in Europe carbon prices are now at very meaningful levels. As one report notes:

In 2022 alone, the EU’s ETS saw the trading of 12.5 billion tonnes of emissions allowances and registered a record-breaking 865 billion euros ($958 billion) turnover, according to Carbon Market Year in Review 2022, published by Refinitiv, a provider of financial markets data and infrastructure.

The EU’s ETS may only cover 3 percent of global emissions, but as a model it can hardly be dismissed. China is building a pricing system for its electricity system, whose emissions alone are larger than those of the United States. Beijing has declared it to be a key policy instrument.

Around the world, climate pricing is not just a figment of the neoclassical imagination. As the IMF comments:

Carbon pricing continues to be adopted by countries, having doubled in emissions coverage since 2015 …. To date, 73 carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETSs) are in operation in 47 countries, covering 25 percent of global GHGs, up from 12 per cent in 2015. National coverage of emissions varies, from below 30 percent in some cases to more than 70 percent in others (for example, Canada, Germany, Korea, and Sweden). Carbon prices vary from below $5 to over $100 per ton (mostly in European countries). The average (emissions weighted) price of covered emissions has grown from $7 in 2015 to about $22 in 2023.

And pricing systems have an expansive logic. Given the significant carbon prices, the EU has no option but to adopt a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), to avoid its industries being undercut by unpriced imports. Despite intense pressure from the Biden administration, Brussels has not fallen in line with America’s non-WTO-conforming quick fixes. The WTO-conformity of Europe’s own system remains to be tested.

The critical decision lies with China. If Beijing reinforces its system of carbon pricing, then carbon pricing will be a common policy of the two blocs that are at this point most credibly committed to long-range decarbonization - the EU and China. They will presumably have to reach some agreement on CBAMs, which will exert considerable pressure on their trading partners.

If Beijing doubles down, carbon pricing as a model will have won an unexpected late victory over its critics. If the Chinese pricing system remains vestigial, then Europe will remain an oddity and the hopes vested in pricing may well be dismissed as a hangover from a by gone age of market economics. It is too soon to tell.

Carbon-pricing is the IMF’s default position. It would drive global pressure to reduce polluting emissions. The novel feature of their recent report is a second feature, their show-casing of the so-called Climate Policy Assessment Tool (CPAT) model, which they have devised to allow

quantification and comparison of mitigation ambition in NDCs for over 150 countries. By estimating emissions for each country in the BAU and comparing to that implied by NDCs, countries can be compared in a transparent, consistent, and fair manner.

In particular, the IMF authors are focused on arbitrating the question of how much decarbonization effort should be expected of high-income countries (HIC i.e. the G7), relative to upper middle-income countries (UMICs, led by China), lower-middle income (LMICs) and low-income countries (LICs), of which India is by far the most important representative.

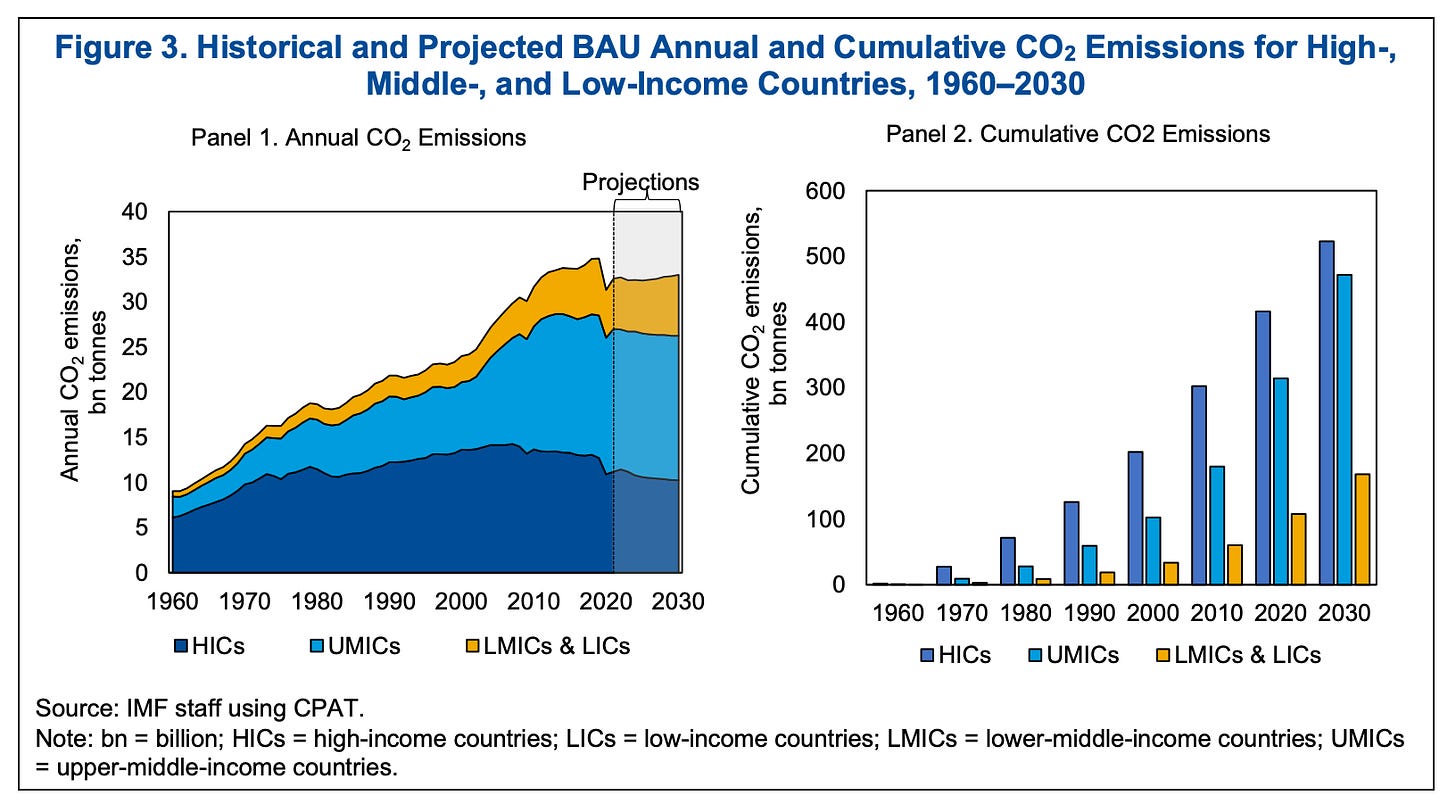

As the IMF points out, the balance between the high-income countries and the upper middle-income countries is rapidly shifting. By 2030 the giant bloc of developing countries (all countries other than the high-income group) will be responsible for 60 percent or more of current emissions and more than half of historic cumulative CO2 as well.

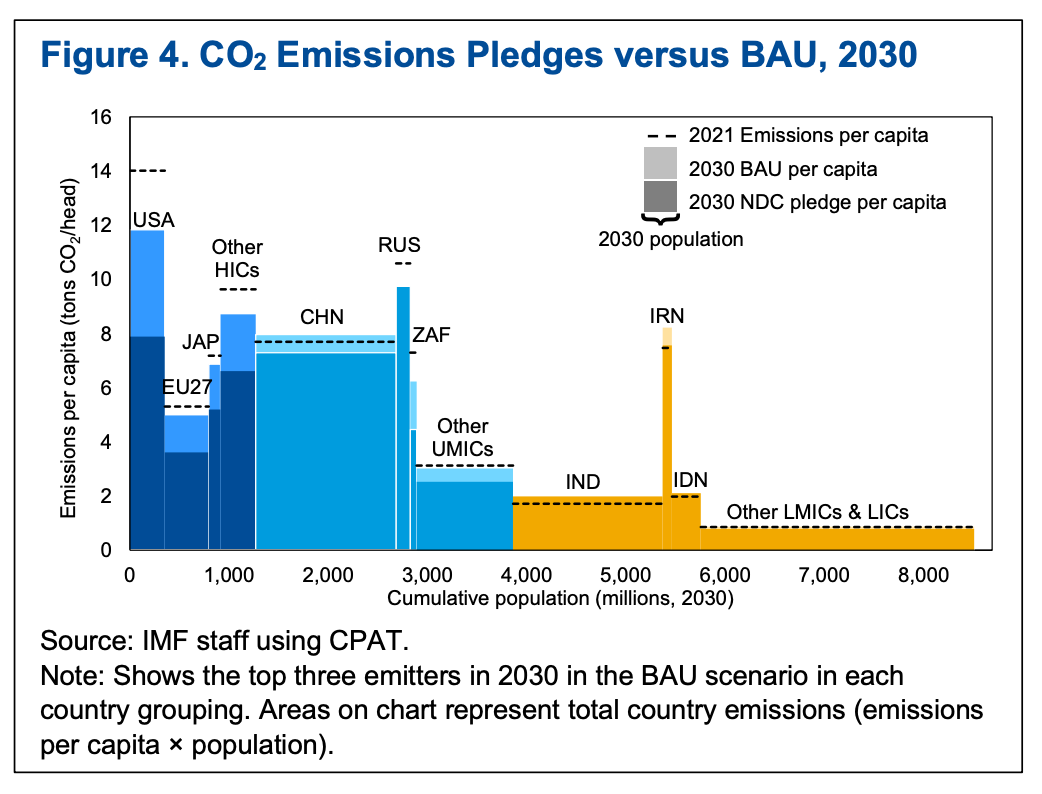

Of course, the population of the “developing” world is far larger than that of the rich-world. But on current policies, if Europe meets its targets, its per capita emission by 2030 will be little more than half those in China.

The IMF team then apply their model to calculate what they call “equitable” trajectories for emissions over coming decades. These are “equitable” in the sense that everyone makes cuts but high-income countries cut harder.

This is reasonable. But looking at the conclusions derived by the IMF’s staff from their CPAT model, one cannot but wonder at its utility and its political implications.

Given the urgency of the crisis, the IMF’s calculations yield remarkably little differentiation between polluters. Of course, the IMF’s call for the US or the EU to slash emissions by 65 percent by 2030 is dramatic. But to have any chance of stopping global warming at 1.5 degrees, the model requires China to make a 55 percent cut. In light of China’s rapid growth in emissions, this is arguably even more extreme than the 65 percent cut required of the high-income countries. We will, in fact, count ourselves lucky if China stabilizes its emissions in the next couple of years. Halving them seems out of the question. Even more implausibly, to give us a chance of hitting 1.5 degrees the IMF calls on India to cut emissions by almost 40 percent in the next seven years. Given that India’s per capita emissions are currently one seventh those of the United States this seems both inequitable and unrealistic.

Of course, these demands are based on the constraint of the carbon budget. If India and China do not cut by as much as the IMF suggests, then even larger and more implausible cuts would have to be made by the rich countries.

All in all, the IMF modeling seems to offer less a practical way forward than a detailed demonstration of the impossibility of achieving the most ambitious climate stabilization goals.

In 2015 aiming for 1.5 degree stabilization was already highly optimistic. It was floated as the desirable objective, because anything else puts the survival of the most vulnerable states in question. 1.5 degrees is now for all intents and purposes out of reach. 2 degrees may still be feasible, but only if the rich countries further raise their ambition. For this the US will not only have to stay the course, an open question given the 2024 election, but accelerate its decarbonization. China, India and the other big middle-income countries will have to perform a hairpin bend.

By far the most likely outlook is that this does not materialize, yielding a grim scenario of a world warming by substantially more than 2 degrees. For the most vulnerable states this spells disaster. Not by coincidence, they are overwhelmingly, weak, poor and powerless. Despite professions to the contrary, given the track record of the rich countries to date, no one should seriously expect a large-scale effort on their behalf. A Loss and Damages fund was finally established just ahead of COP28, but its funding is derisory. A state of affairs worthy of a future Carbon Note.

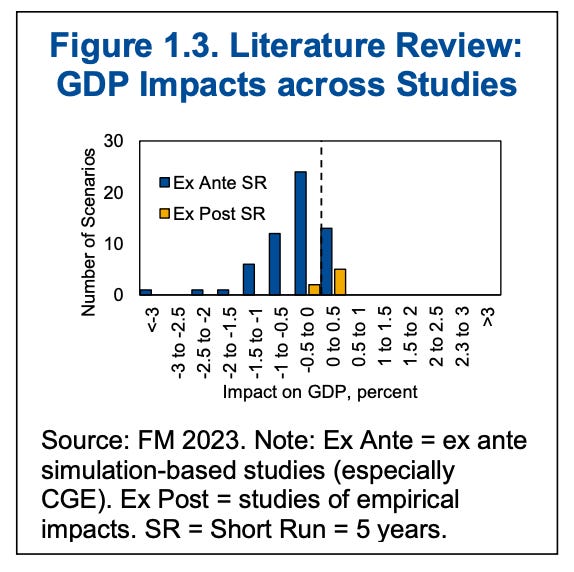

The best hope is that the large polluters accelerate their level of effort out of self-interest. At least if you believe the economic models, the balance of cost and benefit is hugely stacked in favor of action. According to an IMF survey of economic simulations, the vast majority suggest only marginal GDP impacts from full-scale decarbonization.

A carbon pricing based solution would generate a substantial fiscal benefit. And more importantly, running down India and China’s huge coal-fired power complexes would generate enormous collateral benefits from reduced pollution.

On the face of it, decarbonization starting with the rapid phase-out of coal in the largest emitters should not be contentious. It should be an obvious policy choice.

The problem is that the models used to generate that anodyne conclusion do not capture what actually makes it difficult. The question is not whether decarbonization is desirable or even whether it is technically feasible. The steps we need to take by 2030 clearly are within our reach. The central question is whether a coalition can be built to breakthrough the inertia of the existing system and powerful vested interests and not only to add new power but to aggressively run down polluting fossil fuel sectors. Those decisions have to be made within the small group of polluters responsible for the majority of global emissions (G7 plus China plus India). A coalition for a new energy model is emerging but that is not the same as a model for decarbonization which is a far more daunting political proposition.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here: