Chartbook Carbon Notes 8: Betting on climate disaster. The possible futures of the (US) oil and gas industry.

In the last few years, the energy transition has moved from being a wished-for hypothetical to becoming a large-scale global trend. As this happens, it shakes up our understanding of the future. Some analysts are tempted, already, to define our situation as “mid-transition”. That seems bold, not to say premature. How can we define the middle of a process that has only just begun? Perhaps the best way to think of the term “mid-transition” is less as diagnostic than as performative. It may help to make this the middle phase of the transition that some of us urgently hope for, if we insist as loudly as we can that that is where we are - in the middle - and that the end-point is therefore known and certain.

One thing we actually may know better now, is that things can be moved and changed. But the very fact of movement unsettles the fixity of our expectations. This makes it all the more interesting and urgent to map possible paths ahead and to gauge how powerful actors in the system may be seeing the future.

Reading the reports of the International Energy Agency is one way of tracking how centers of power/knowledge are doing this in real time. Two recent reports one on energy investment, the other on the future of the oil and gas industry are particularly interesting.

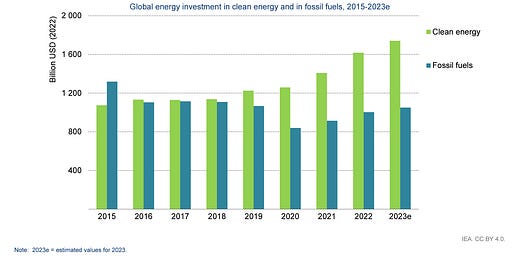

Looking at the global energy investment numbers it is clear that the energy transition has begun.

Since 2016 clean energy investment in the broadest sense has inched ahead of new investment in fossil fuels. Since 2020, when fossil fuel investment slumped and clean energy investment surged, the gap has opened wide.

The shift is far from sufficient to offer us a sustainable future. These figure are for annual additions to gigantic energy systems that will take decades to shift. Furthermore, though the balance has shifted, the current flows are nowhere near enough. At a rough estimate, new clean energy investments need to be running at a rate three times higher than the current record pace and new fossil commitment must be cut by half by 2030. But the shift is nevertheless significant. We may, indeed, look back on 2015-2020 as the moment when the energy transition began. But what kind of transition this will become and what the mid-point will be is still far from clear. The only thing that is undeniable is that the status quo is giving way.

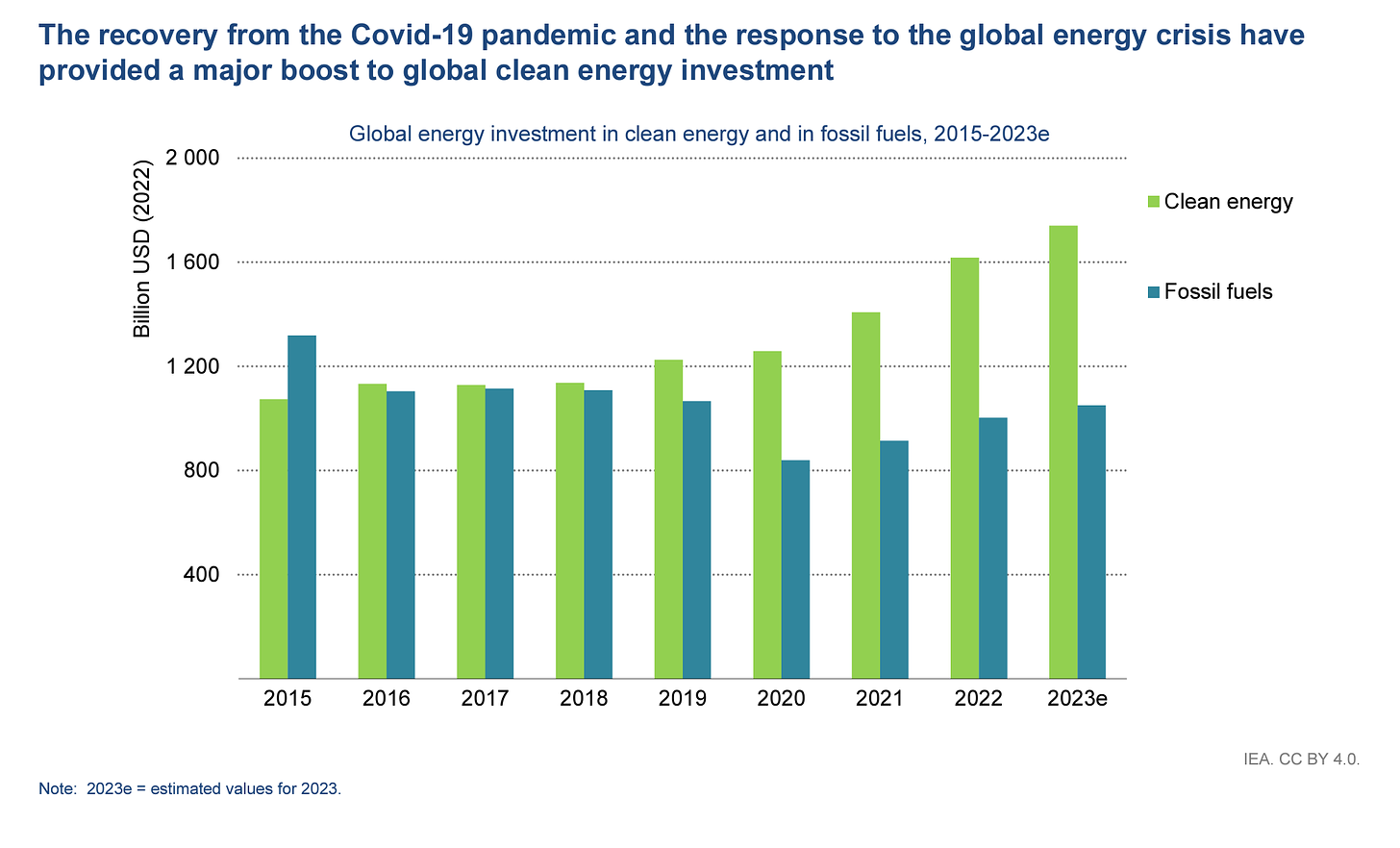

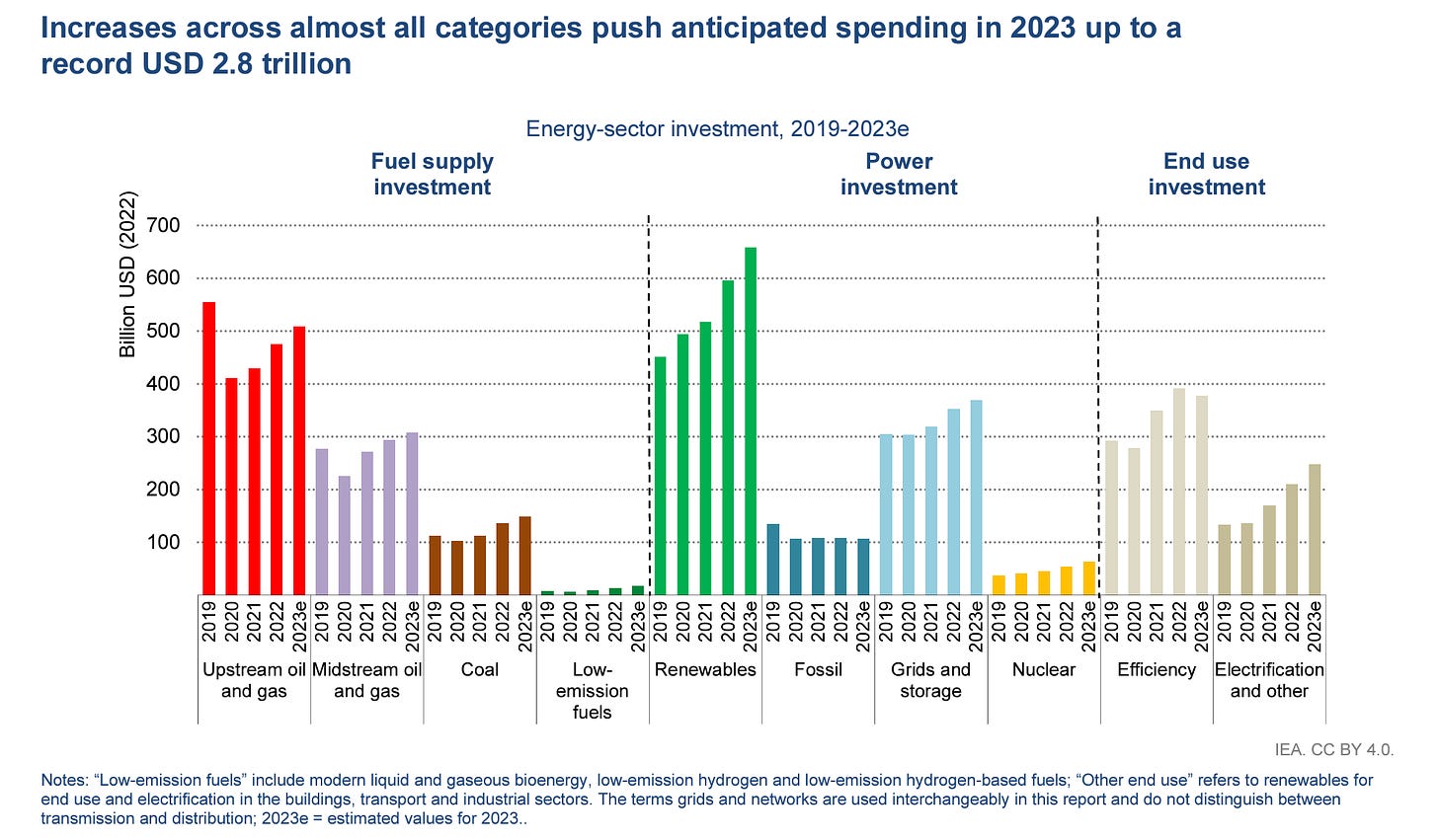

The leading edge of the transition is electrification. The IEA show surging investment in green power generation (solar, wind), electric mobility (EVs) and to a lesser extent electrical grids and and efficiency. Worldwide, solar and wind - once the domain of woolly-jumpered eco freaks - are now attracting 30 percent more new investment than upstream oil and gas. It is worth pausing to take in that fact.

Historically, electrification has sat side by side with the oil-based energy system that drives motor transport. Gas and coal are fed into electrification through power generation. But, with renewable electricity generation becoming ever cheaper and electrification spreading pervasively across all sectors of the economy and society, over the coming decade, green electrification is set to swallow a larger and larger share of the overall energy business. It will progressively eat into demand for coal, gas and oil. This at least is the optimistic scenario sketched by net zero planning (NZE). It is also the future to be expected on current announced policies (APS scenarios). Current policies will not achieve climate stabilization, but at this point you would be going out on a limb to bet on the persistence of the fossil-fuel dependent world as we know it today.

How rapidly the run-down of fossil fuel use happens, will decide our climate future. It will also decide the future of incumbent oil, gas and coal industries.

As measured by emissions, the most important sector in decarbonization is the unglamorous business of coal-fired electricity generation. But oil and gas are the most high visibility and salient sectors from the point of view of global political economy. This is particularly true in the USA. America has large coal-fired power systems that have powerful political voice, take a bow Senator Manchin from the coal-state of West Virginia. But it is oil and gas in the form of global oil majors and the more “medium-sized” fracking interests that dominate the agenda. The future of America’s oil industry no longer encapsulate the global energy transition problem. To think in those terms is an anachronistic hangover of the 1980s and 1990s. But it does matter. It matters politically in the US and also, as the IEA projections allow us to see in sharp relief, on the global scale.

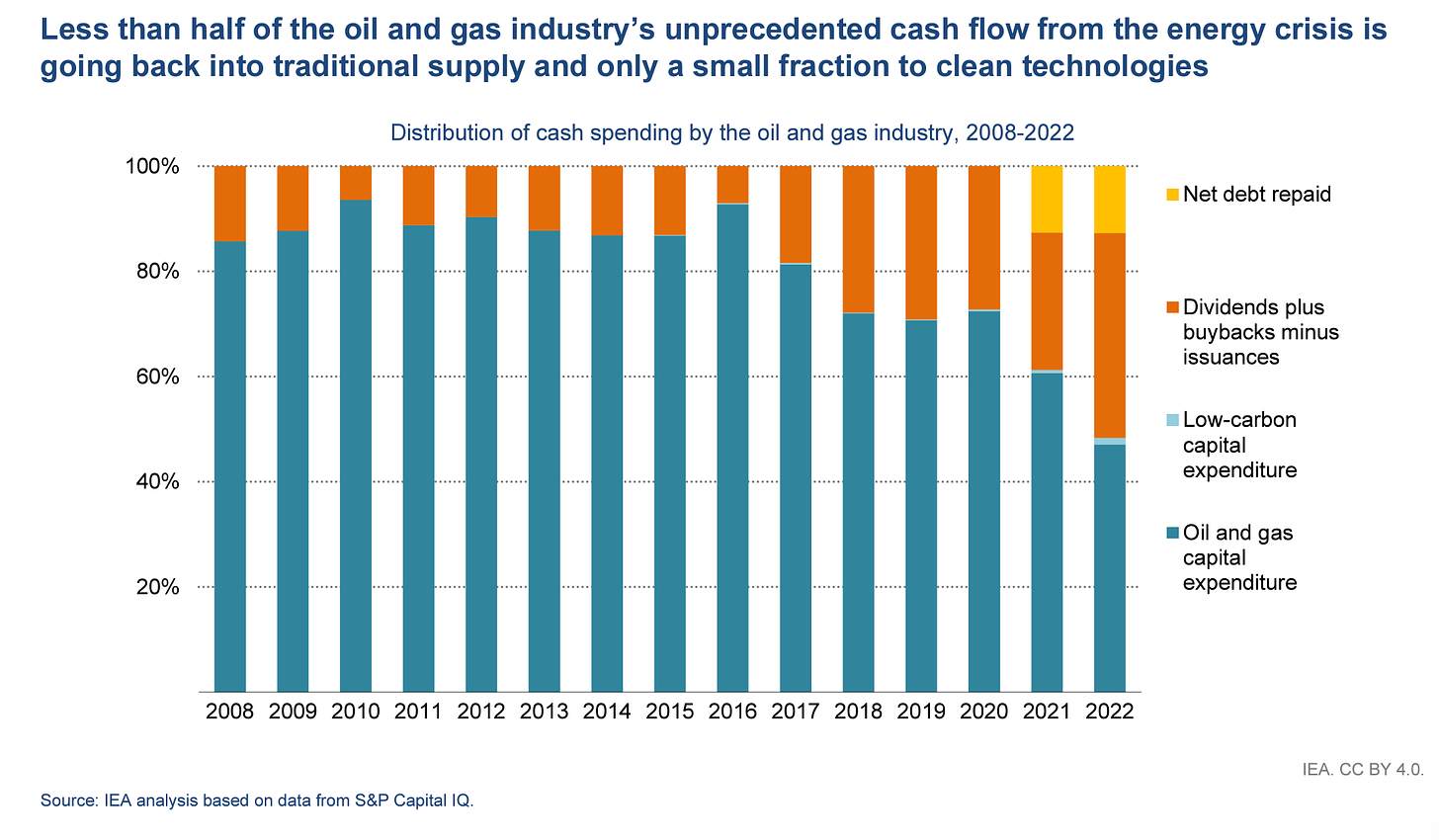

As is clear form the investment data, the oil and gas industries are not yet shrinking, but their growth has slowed and if you look underneath the bonnet there are telltale signs that the industry is beginning to reevaluate its future. Notably, the huge surge in revenues generated by the energy price hikes of the last two years has not been poured into new investment. It has been used to pay down debt and to pay out dividends.

What this suggests is that the owners and managers of the fossil fuel complex are increasingly anticipating a constrained future. To keep their shareholders happy and their stock market valuations up, they are deleveraging and paying out larger dividends. Investment is flat, but what is not happening so far to any significant degree is a move by the existing oil and gas industry either to cut investment to long-run sustainable levels or to join the energy transition. We are in a situation of suspended animation, or suspended disbelief.

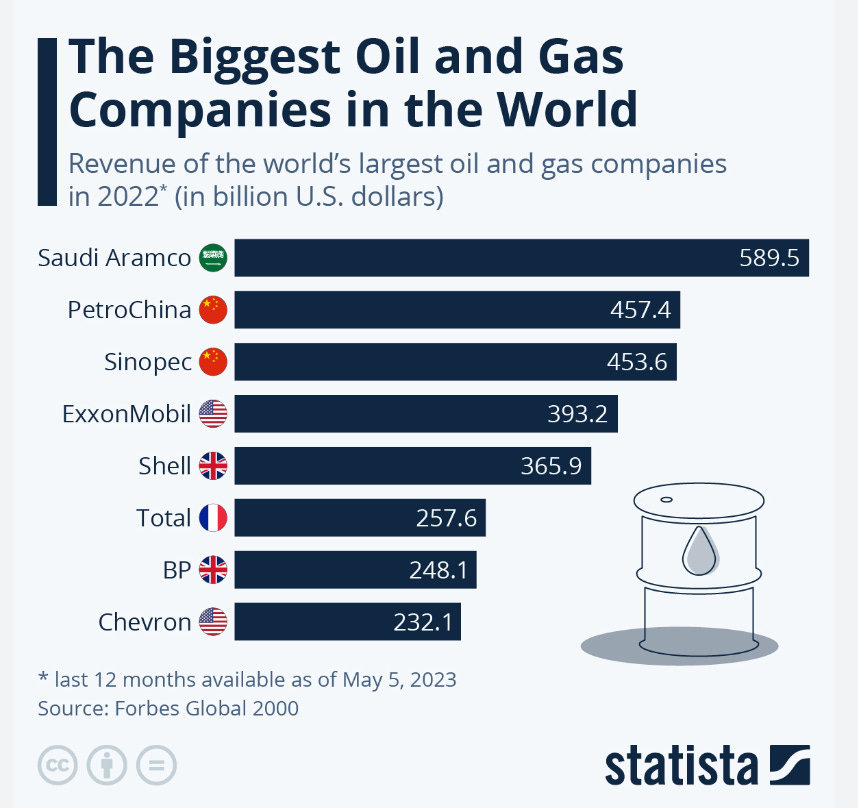

The aggregate data, however, hide important and telling differences. Again we have to remind ourselves that the global oil and gas industry is not dominated by the Western energy majors but is a mixed economy of large global players, smaller independents and various nationally owned energy corporations. The largest of the national oil companies Saudi Aramco dwarfs all the other players. And it was followed in the rankings in 2022 not by ExxonMobil, but by the two Chinese giants, PetroChina and Sinopec.

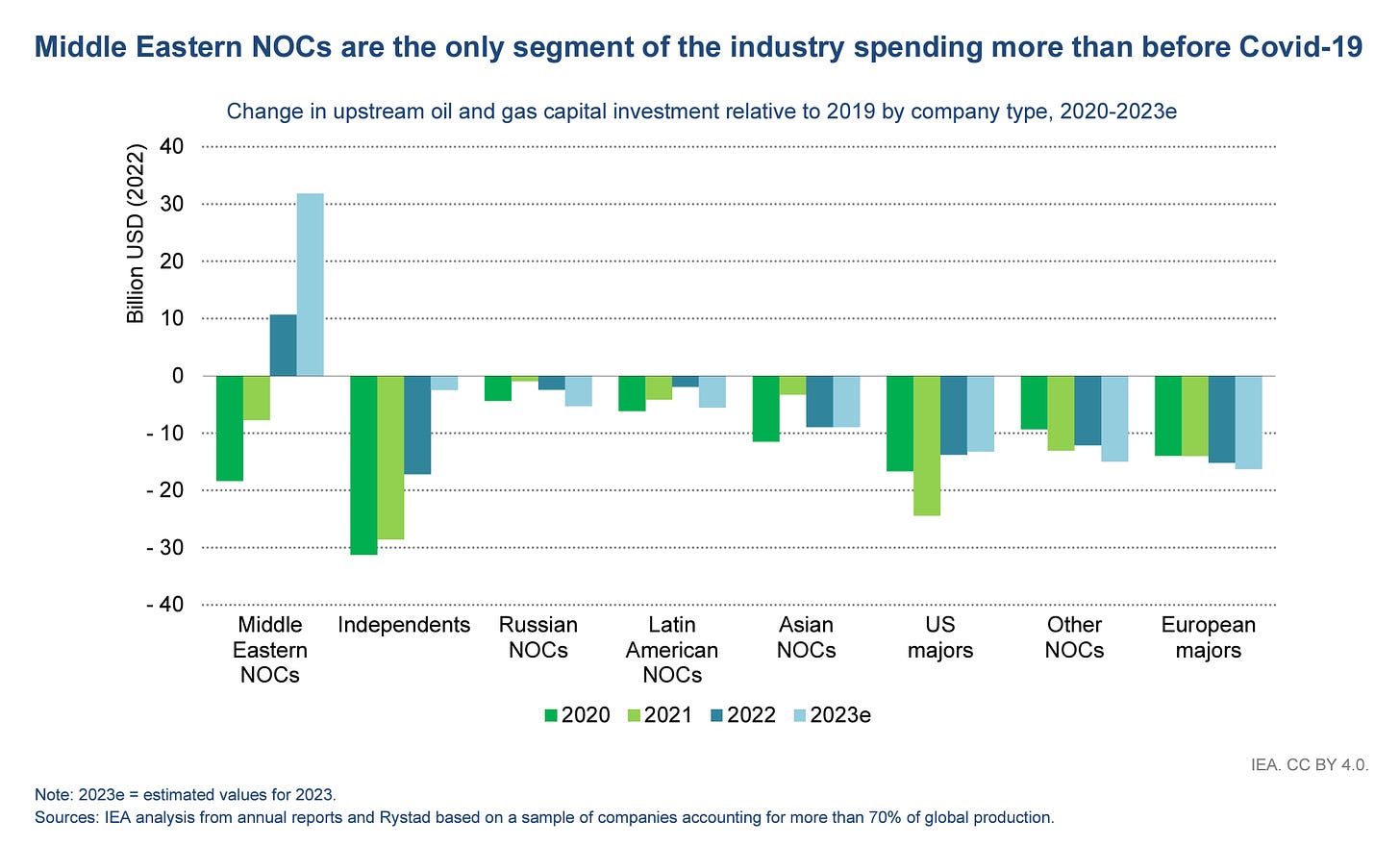

The national oil companies are also paying large dividends and taxes enabling their governments to fund alternative investment programs. But the Middle Eastern national oil and gas champions are not just flooded with cash. Their business decisions reveal that they are also comparatively optimistic about the future. They are responding to a surge in revenues by increasing investment. By contrast, investment by private oil interests, whether the majors in the US and Europe or the independents, is well down.

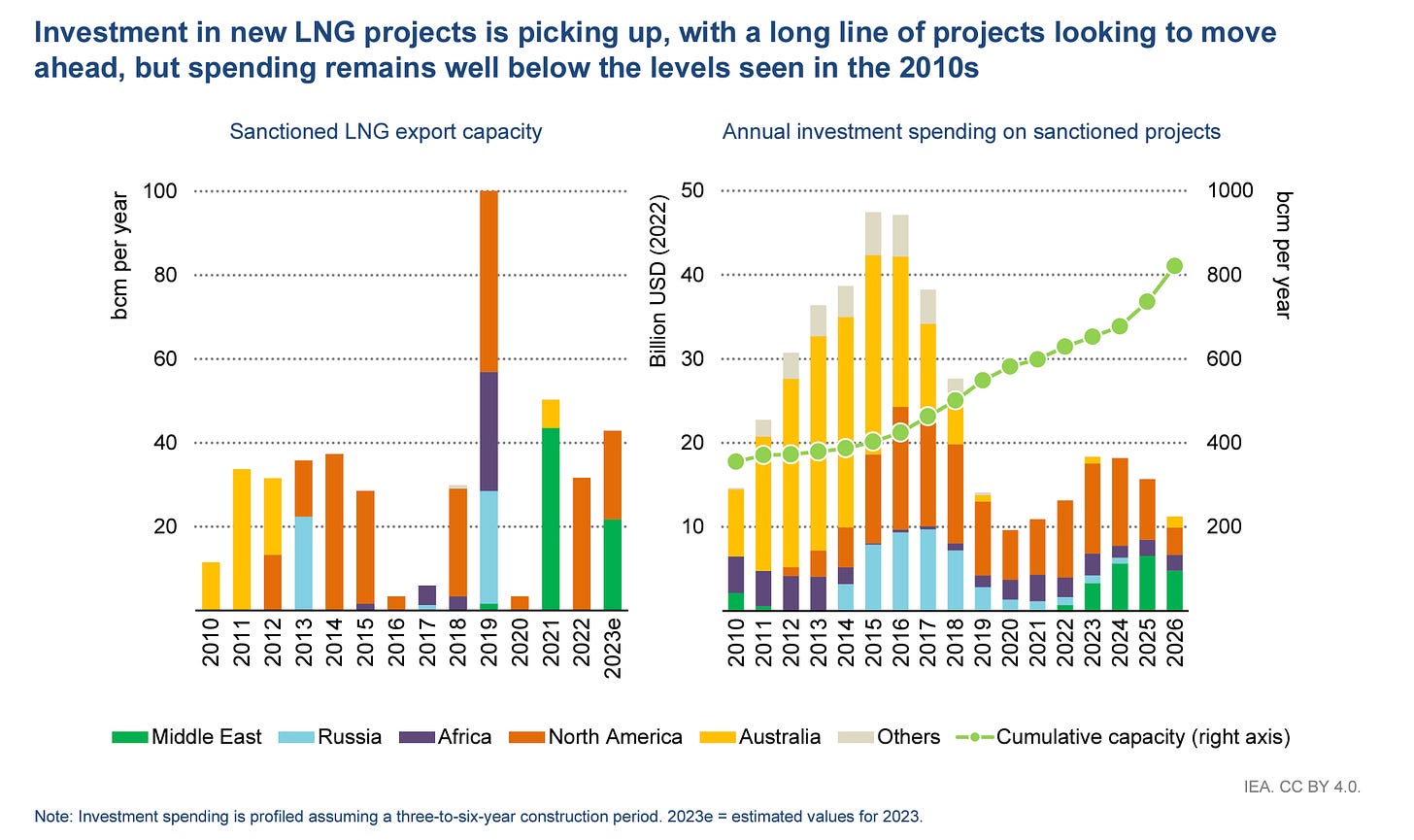

Even in sectors like LNG, that have been in the headlines and where significant excess capacity is likely by the end of the decade, new investment is nowhere near the peaks it hit ten years ago.

If we diagnose a state of something like suspended animation, of an industry holding its breath, can we give more contour to the futures that these numbers imply?

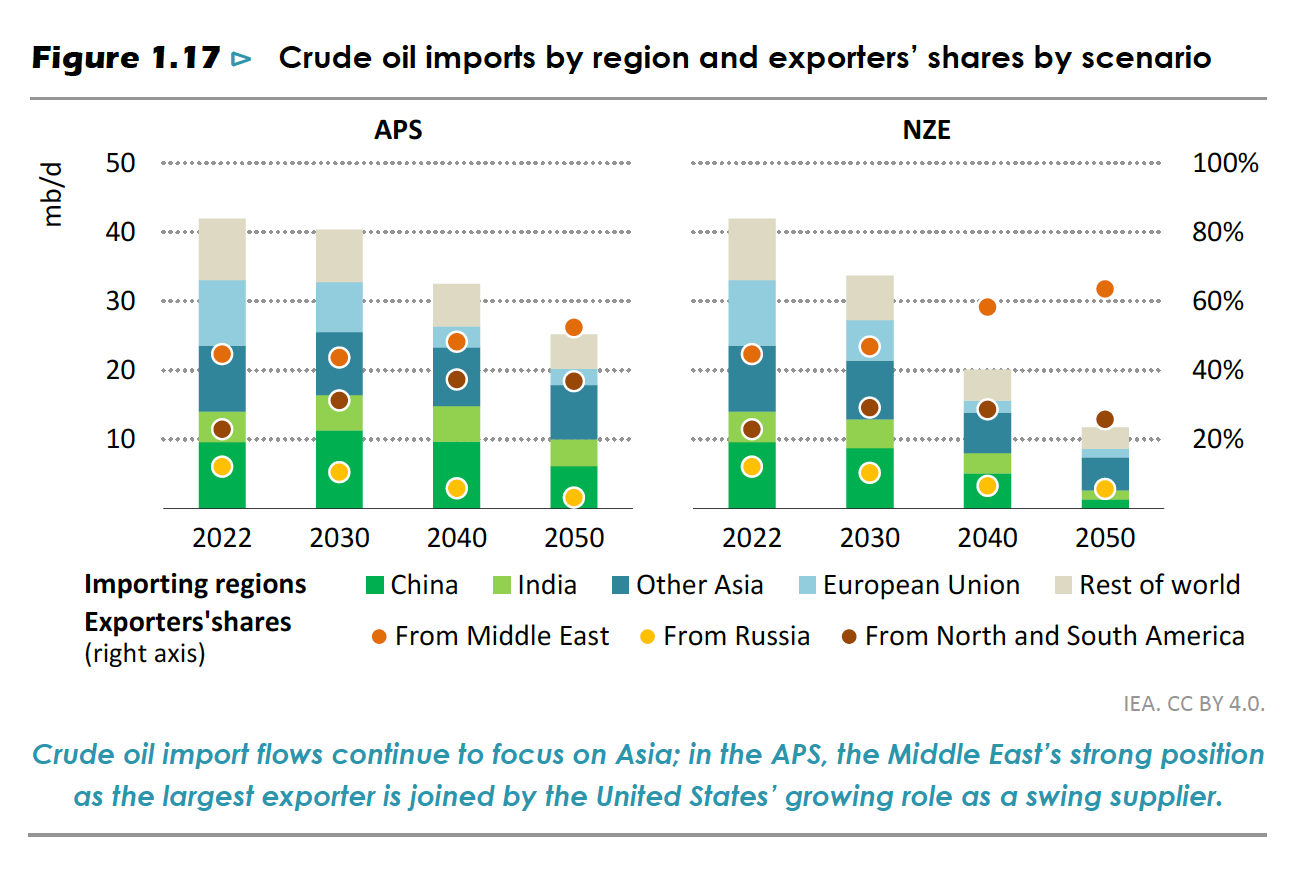

One possible answer is provided by the IEA’s outlook for the future geography and scale of the global trade in oil and gas. In these projections, APS is the announced policy scenario. This is how the IEA expects the world to look if governments follow through on their existing commitments. NZE - net zero by 2050 - is the IEA’s in-house climate stabilization benchmark.

Source: IEA

Both scenarios suggests that the global trade in oil and gas is presently at its peak. By 2050 both scenarios foresee a significant decline in the global trade. This is driven by the falling imports of the EU, China and India. The one really resilient area of demand foreseen by both scenarios is “Other Asia”, which by 2050 in the NZE case accounts for more than half of total global demand.

Regardless of the scenario, the Middle East is the main source of supply for oil and gas by 2050. In both, Russia is largely squeezed out. The crucial difference between the two scenarios concerns North America and above all the USA as a source of oil and gas exports.

In the net zero transition scenario, as overall trade in oil and gas is slashed by 75 percent and the Middle Eastern share of global trade rises from 40 to 60 percent, the US share remains frozen at 20 percent. Given the collapse in overall global demand this means that the future for US fossil fuel exporters is bleak. To be clear, these figures are for the global trade in oil and gas only. There will likely be substantial residual fossil fuel demand within North America on either scenario. But, even allowing for this, the NZE scenario does not support aggressive investment, certainly not for export purposes.

In the announced policy scenario, the outlook is quite different and most particularly for the North American industry. The overall reduction in trade is far more modest - from c. 40 m barrels per day to c. 25 million - and in this less competitive market, the North American exporters squeeze out higher-cost producers and establishes themselves as the swing producer alongside the Middle East. The North American share of global oil and gas markets doubles from 20 to 40 percent. The two trends off-set so that on announced policies, the IEA expects US exports of oil, gas, hydrogen etc to remain largely unchanged at roughly 9-10 million barrels per day as far ahead as 2050.

The contrast is stark. Russia has a poor outlook regardless of the scenario. But for the US the scenario makes all the difference. On the trajectory suggested by current policies, there is a future for North American exports at something like their current scale. On a net zero path the North Americans, like everyone else, are squeezed to very low levels by Middle East cost advantages.

This then is a measure of the energy policy battlefield of the coming decades. The interest of the US oil and gas interests lies not in stopping the energy transition tout court, but to ensure that it is gradual enough to secure for them a substantial global market, which will valorize investments still being made to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. The IEA’s scenario analysis precisely identifies the global scenario for which the US oil giant ExxonMobil and other interests in Texas and the Gulf seem to be preparing themselves.

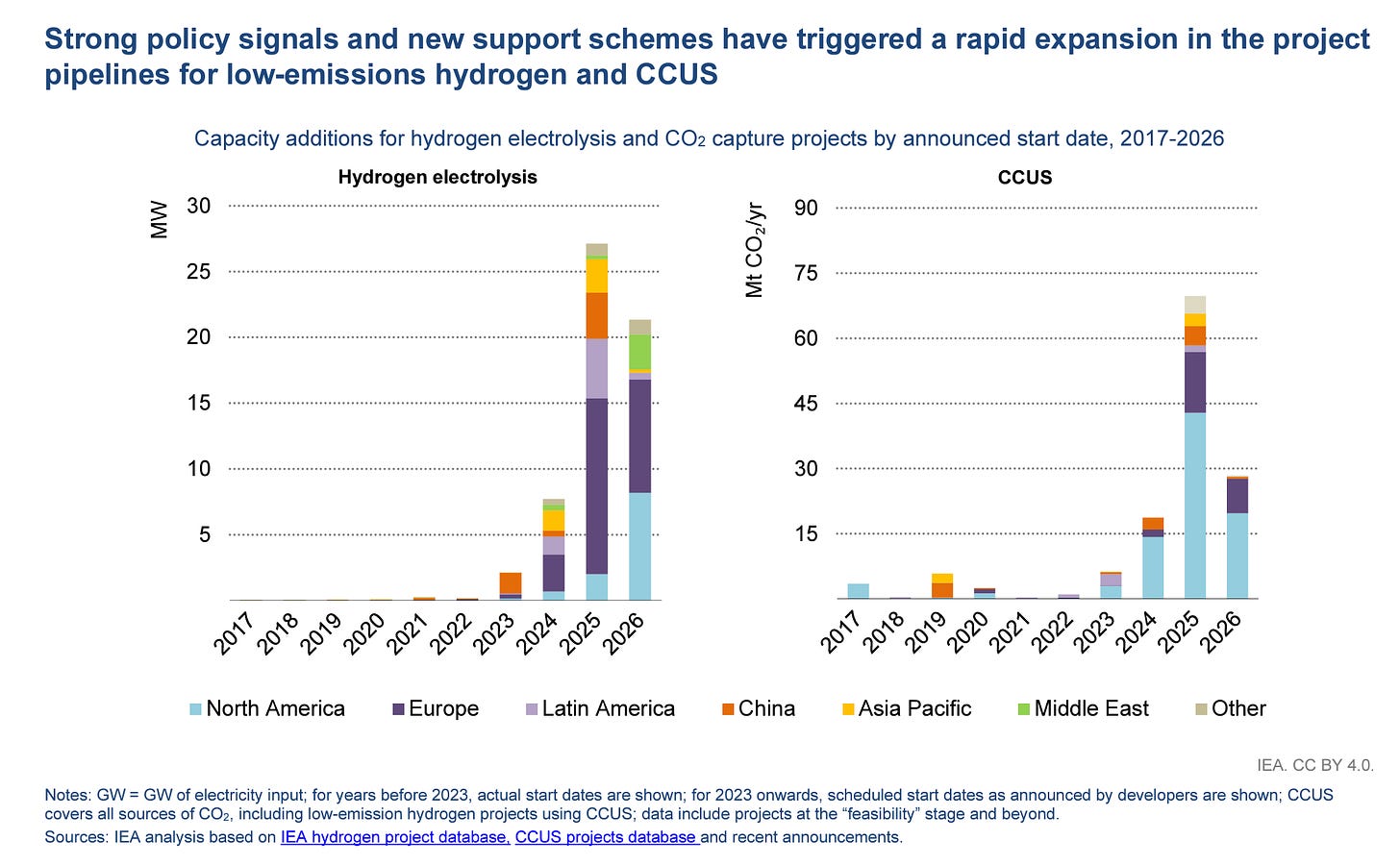

The US industry is flanking this with substantial investments in various alibi technologies like carbon capture, where the US lead on future projects is large.

The US is also catching up in hydrogen, where its investments to date are modest, but its share of new investment projects has leapt.

Much of the impetus for this American surge in fossil-aligned “clean energy” projects, has come from the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022, which provides generous subsidies for carbon capture and hydrogen.

This in part reflects the lobbying and horse trading that goes into the making of all legislation. To get the IRA deal done, the underlying model was bottomless mimosas (Sahay) - open-ended subsidies for “everyone”. But this outcome also reflects the cornucopian, “all of the above” approach to energy policy that the Biden administration inherited from the Obama administration. Faced with energy price pressure in 2021-2023, the Biden administration has lobbied hard to promote both domestic oil and gas production, American energy exports and greater production by Saudi-led OPEC.

The green wing of the Biden administration justifies this as a political necessity. But there are more than short-term factors in play. American policy talks a good game on the global energy transition but American business interests and policy-makers like their new role as a major energy exporter. Policy-making at all levels clings to the idea that the US will be a major energy provider for the world economy. It is not focused on preparing US energy interests for a future in which their energy exports are slashed to half their current level by 2040 and a quarter by 2050. To this extent, to the extent that they project energy exports at anything like the current level into the medium-term, they are effectively betting on an incomplete transition.

This in turn helps us to make sense of the investment data. The suspended animation that the IEA sees in the oil and gas investment figures reflects this undecided status quo. Continued investment in the Middle East energy complex, which has a future under any scenario, sits side by side with stagnation, but not full retreat in the private, North America-centered, oil and gas business.

The risk is that as this situation persists and the investments in the status quo pile up, even if at a slower pace, it opens the door to reactionary forces and questioning of the underlying trajectory of transition. In the limit the direction of travel itself is put in questio. Meanwhile, the carbon budget runs down at an even more alarming pace. We thus find ourselves not in mid-transition, but in mid climate disaster.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

You misinterpret the data.

What you are seeing is a massive government-subsidized and mandated investments in Green energy and wide-spread government constraints on investment in fossil fuels. This is not evidence of an energy transition.

You need to focus on outputs, not inputs.

The reality is that green energy is not replacing fossil fuel usage. It is in addition to widespread usage of fossil fuels.

This analysis, with an obvious green left wing angle, obfuscates or perhaps deliberately deceives by stating that wind and solar are getting cheaper and remains silent about how govt subsidies are creating this unsustainable inversion. After global investment of over $5 trillion, wind and solar have only taken over 3-4% of energy production with fossil still supplying 80% of world energy needs. An astute observer grounded in reality will recognize that this amount of continued investment is unsustainable and fossil fuels will play a huge role well beyond 2050 and into the 22nd century. With the world already close if not at 1.5c temp rise, with no apprent disaster in sight, political will for further wasted low EROI supply will diminish significantly.