Chartbook Carbon Notes 7 - The IEA's message to the oil and gas industry: wake up!

A moment of truth is coming for the oil and gas industry

This is the opening line of the International Energy Agency’s latest report on the global oil and gas industry in the energy transition.

Around 97 mb/d of oil and 4 150 bcm of natural gas were consumed globally in 2022. This resulted in just over 18 Gt CO2 emissions, around half of total energy-related CO2 emissions.

Clearly, if we are to achieve anything like climate stabilization, this giant industry has to be wound down at a dramatic pace. As the IEA remarks:

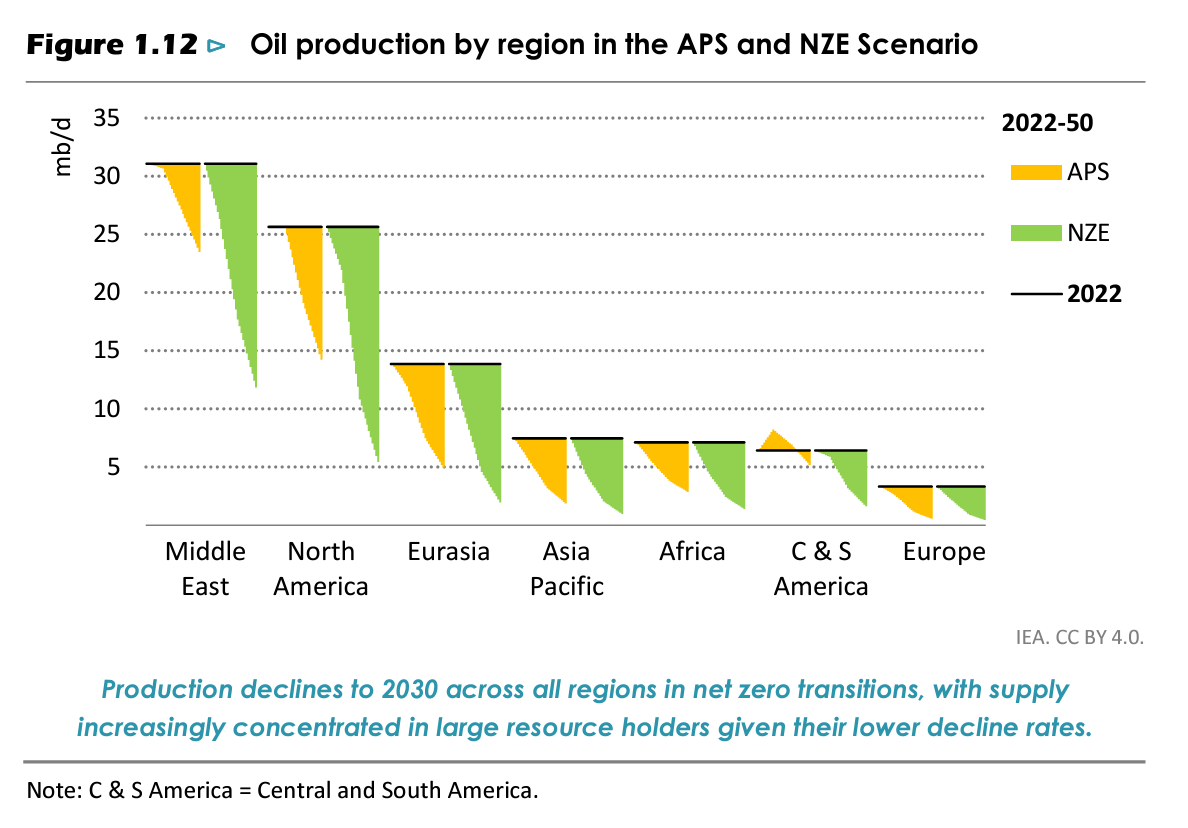

Structural changes in the energy sector are now moving fast enough to deliver a peak in oil and gas demand by the end of this decade under today’s policy settings. After the peak, demand is not currently set to decline quickly enough to align with the Paris Agreement and the 1.5 °C goal. But if governments deliver in full on their national energy and climate pledges, then oil and gas demand would be 45% below today's level by 2050 and the temperature rise could be limited to 1.7 °C. If governments successfully pursue a 1.5 °C trajectory, and emissions from the global energy sector reach net zero by mid-century, oil and gas use would fall by 75% to 2050. …. In the Announced Pledges Scenario (APS), oil and gas demand decline by around 2% each year on average to 2050 (to 55 mb/d and 2 400 bcm) and in the Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) Scenario they fall by more than 5% each year on average to 2050 (to 24 mb/d and 920 bcm).

If this is to be our future, the question is how will the industry adjust? Will it contribute to the transition or divert, deflect or even resist it? You might think that the answer is simple. The fossil fuel industry is an obstacle to a green future that needs to be swept aside. And there are some hold outs, whose overt resistance to climate politics, merits that simple view. But this is not the normal MO of global capitalism. In fora like the Davos meeting of the WEF, energy companies like to pose as enlightened stewards of the planetary future. They boast of their commitments to green energy projects and make promises of carbon neutrality. It is this politics of greenwashing against which the IEA’s report is targeted.

The IEA is a government-backed agency at the heart of the energy policy community, so we should not expect pipeline-smashing radicalism. Perhaps the degree of hypocrisy and cognitive dissonance is simply becoming too much. In any case, the tone of the IEA’s report this year is strikingly direct in calling out the oil and gas industry for failing to grasp the scale and pace of the transition.

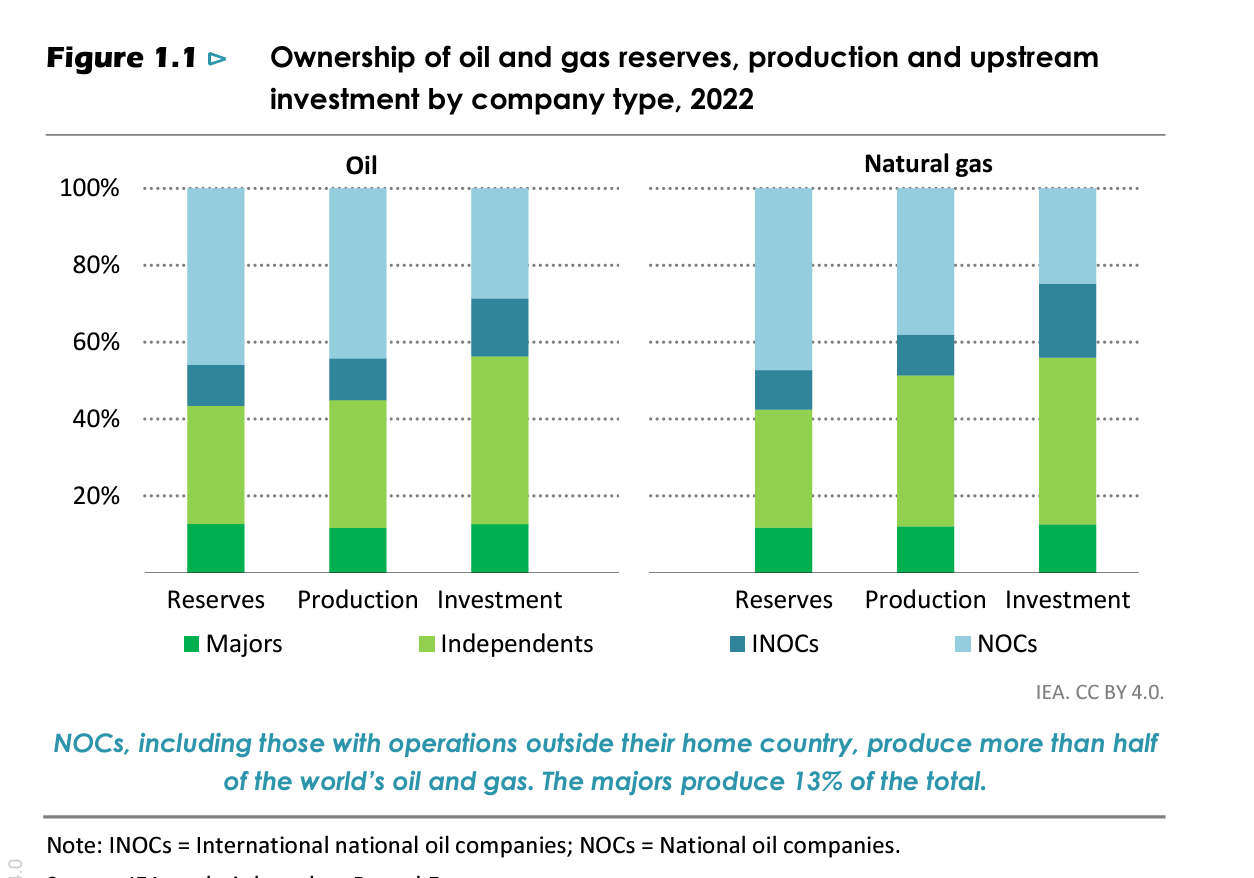

To start with, as the IEA comments, it is important to get clear what the oil and gas industry consists of. The industry is vast, employing 12 million people and generating free revenue of roughly $3.5 trillion, which is split between government taxation (50%), reinvestment (40%) and dividends (10%). In the West, notably in the US and Europe, we tend to think of the energy industry as consisting of “oil majors”. Giant private corporations like Exxon. But that is an outdated view, today the 7 global oil majors “hold less than 13% of global oil and gas production and reserves. National oil Companies (NOCs) account for more than half of global production and close to 60% of the world’s oil and gas reserves.”

From their limited base of reserves, the Western, publicly traded oil majors extend their influence through a network of joint ventures and partnerships. These serve to share expertise and spread risk. They blur the dividing line between public and private enterprise in what is a thoroughly mixed economy.

The largest share of investment in the industry is accounted for not by the majors or the national oil companies, but by so-called independents which, as the IEA comments:

encompass a wide range of companies, such as Lukoil, Repsol, OMV and Woodside, as well as many North American companies – including shale gas and tight oil players – such as Apache, Hess, Marathon Oil, Pioneer Natural Resources and Oxy, and diversified international conglomerates with upstream activities, such as Mitsubishi Corp.

As the IEA report makes clear, for all its rhetoric about a green energy future, the vast majority of this sprawling industry is “watching the energy transitions from the sidelines Oil and gas producers account for only 1% of total clean energy investment globally. More than 60% of this comes from just four companies, out of thousands of producers of oil and gas around the world today. For the moment the oil and gas industry as a whole is a marginal force in the world’s transition to a clean energy system.”

The oil and gas industry’s talk of a green future, is mainly propaganda. But as the IEA reminds us, that does not mean that the energy transition is a fantasy. It is happening. The balance of new energy investment has shifted decisively from fossil fuel to new energy sources. It is just that other corporate players and government policies are driving it, outside the fossil fuel sector.

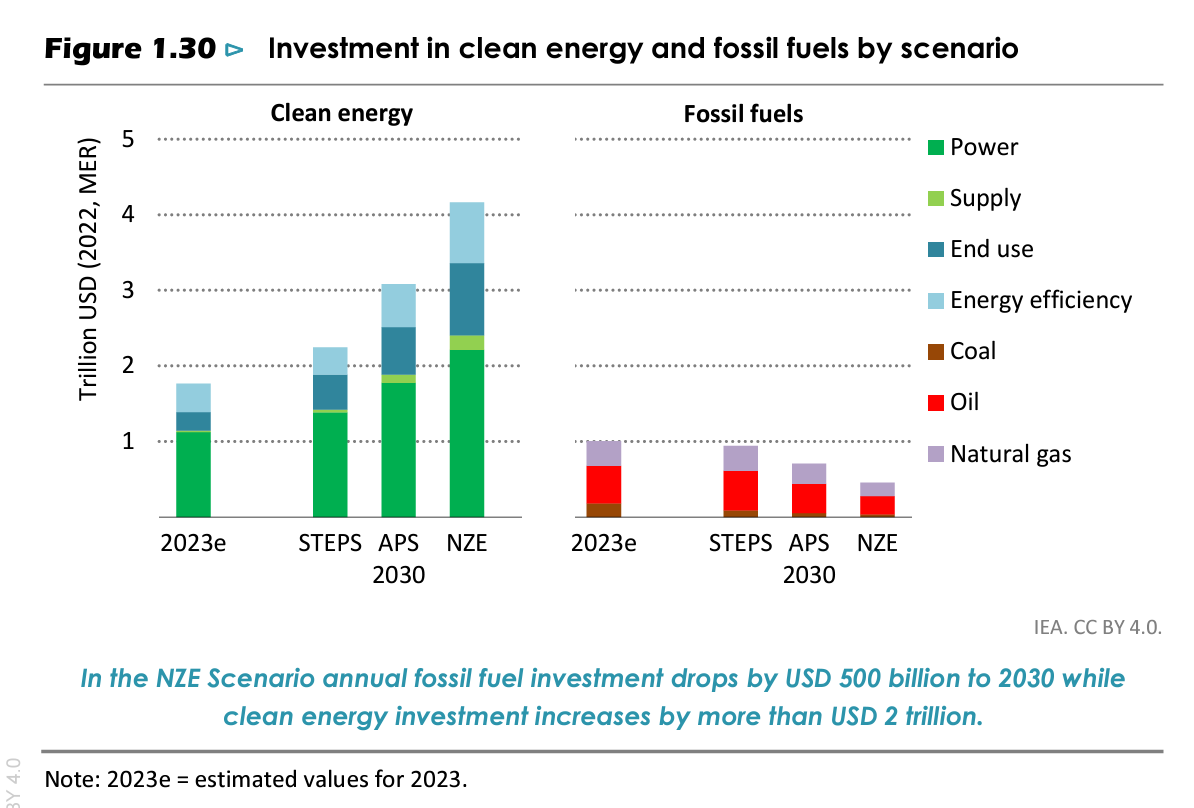

Total energy investment in 2023 is estimated to be USD 2.8 trillion. Of this, around USD 1.8 trillion will be invested in clean energy (including EVs and the like), and USD 1 trillion in oil, gas, and coal (including extraction, refining, transmission and distribution, and power plants that use these fuels).

By 2030 on a net zero scenario, investment in clean energy will be ten times larger than in fossil fuels. What the IEA wants to know is how the oil and gas industry continues to justify investing at least $800 billion annually in fossil fuel infrastructure, whose days are numbered.

Either the oil and gas industry is silently gambling that the energy transition will not happen, that we remain in the so-called STEPS scenario, which spells disaster for the planet. Or, if one assumes that current trends continue and politics and other non-fossil business interests are now driving an inexorable energy transition, then one can hardly avoid the conclusion that the titans of the oil and gas sector are burying their heads in the sand. It is not the green energy advocates but the fossil fuel holdouts who are losing their grip on reality.

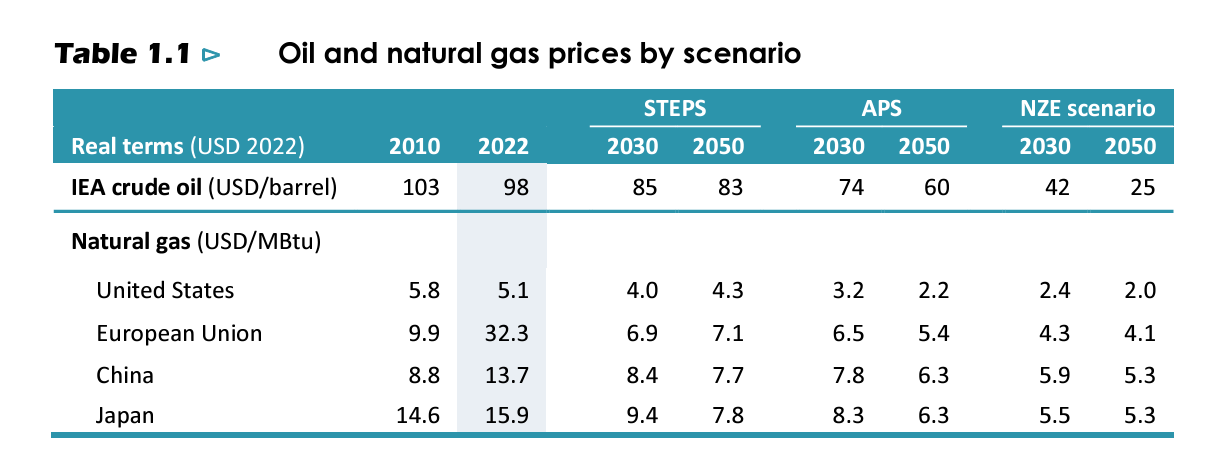

As the IEA comments, if “expectations are that demand and prices follow a scenario based on today’s policy settings, that would value today’s private oil and gas companies at around USD 6 trillion. If all national energy and climate goals are reached, this value is lower by 25%, and by 60% if the world gets on track to limit global warming to 1.5 °C.” Due to their much larger reserves, the losses of the National Oil Companies will be proportionally heavier.

What drives these losses is falling demand and falling prices. In the IEA’s net zero scenario, the oil prices falls to 42 dollars per barrel by 2030 and 25 dollars by 2050, at which point most of the industry is making heavy losses.

Of course exiting oil and gas and entering renewable energy comes with costs and risks and it is commonly said that green energy projects are not “investible”. But according to the IEA , “the return on capital employed in the oil and gas industry averaged around 6-9% between 2010 and 2022, whereas it was 6% for clean energy projects.”

The industry’s ongoing investment of hundreds of billions in fossil energy thus exposes its stakeholders to considerable risks for only modest immediate advantage in terms of secure return.

To bridge the “cognitive gap”, oil and gas managers help themselves with various more or less escapist arguments.

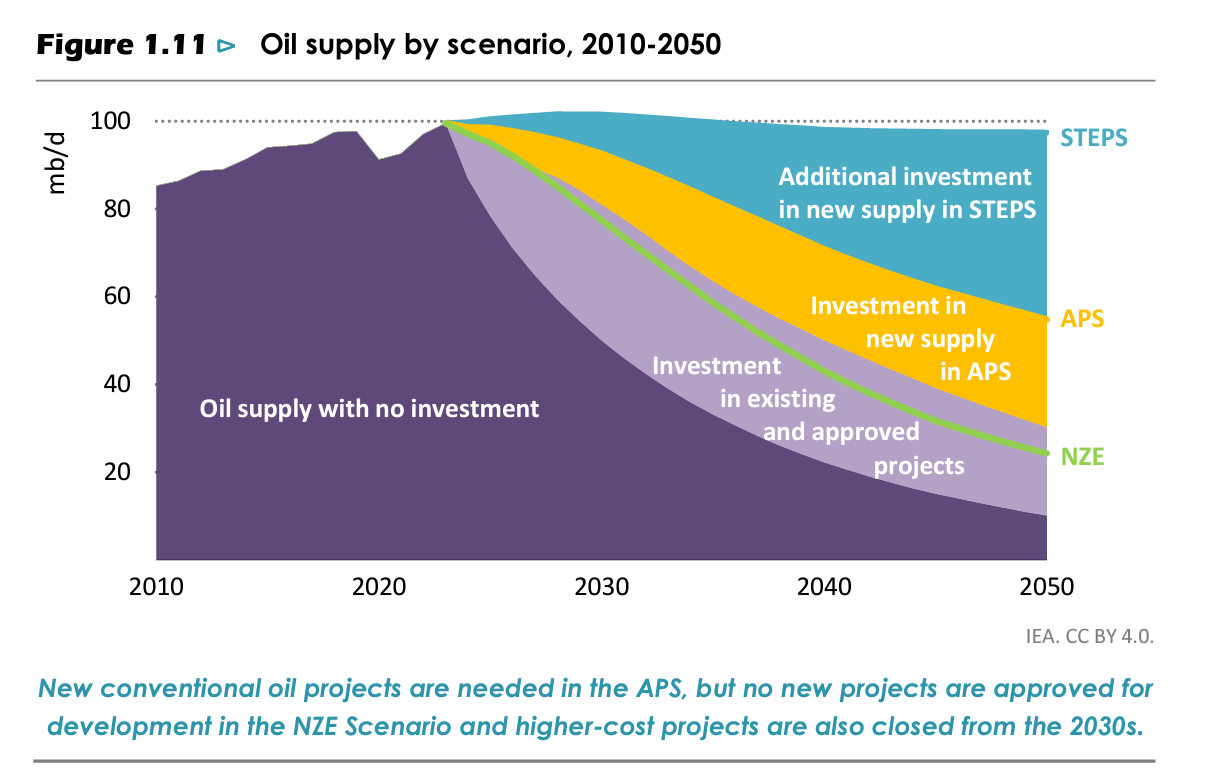

One common argument is that some new investment in fossil fuels is necessary to offset the natural decline in production from exhausted oil and gas fields and to ensure continuity of supply. But as the IEA calculates by 2030 the total annual new investment required is $400 billion, half the current level, and what is certainly not needed is further investment in the discovery of new fields, which is still proceeding apace.

The bottom line is that by 2050 in a 1.5 °C scenario, global oil consumption will be 24 million barrels per day, which is roughly one quarter the current level. Most of this will be used in petrochemicals rather than in combustion. There will also be demand for 920 billion cubic metres of natural gas, roughly half of which will be used for hydrogen production. Rather than seeing this as a clear signal of the need to prepare for dramatic contraction, “Many producers say they will be the ones to keep producing throughout transitions and beyond.” But as the IEA points out

They cannot all be right. Not all producers can be the last ones standing.

What will determine the balance of future supply will be first and foremost costs and this dramatically favors the lowest cost producers in the Middle East. Middle East energy is not only cheaper it is also cleaner to produce. So the future for dirty and high-cost producers in the rest of the world looks bleak, unless national security priorities or other non-economic concerns intrude.

If those factors do not intrude, the IEA’s net zero trajectory foresees a 80 percent contraction in US and Eurasian oil production, compared to a 50-60 percent fall in the Middle East. Even in the Middle East, if market forces prevail, it will be only the very strongest producers - the Saudis, Emiratis and Qataris that survive.

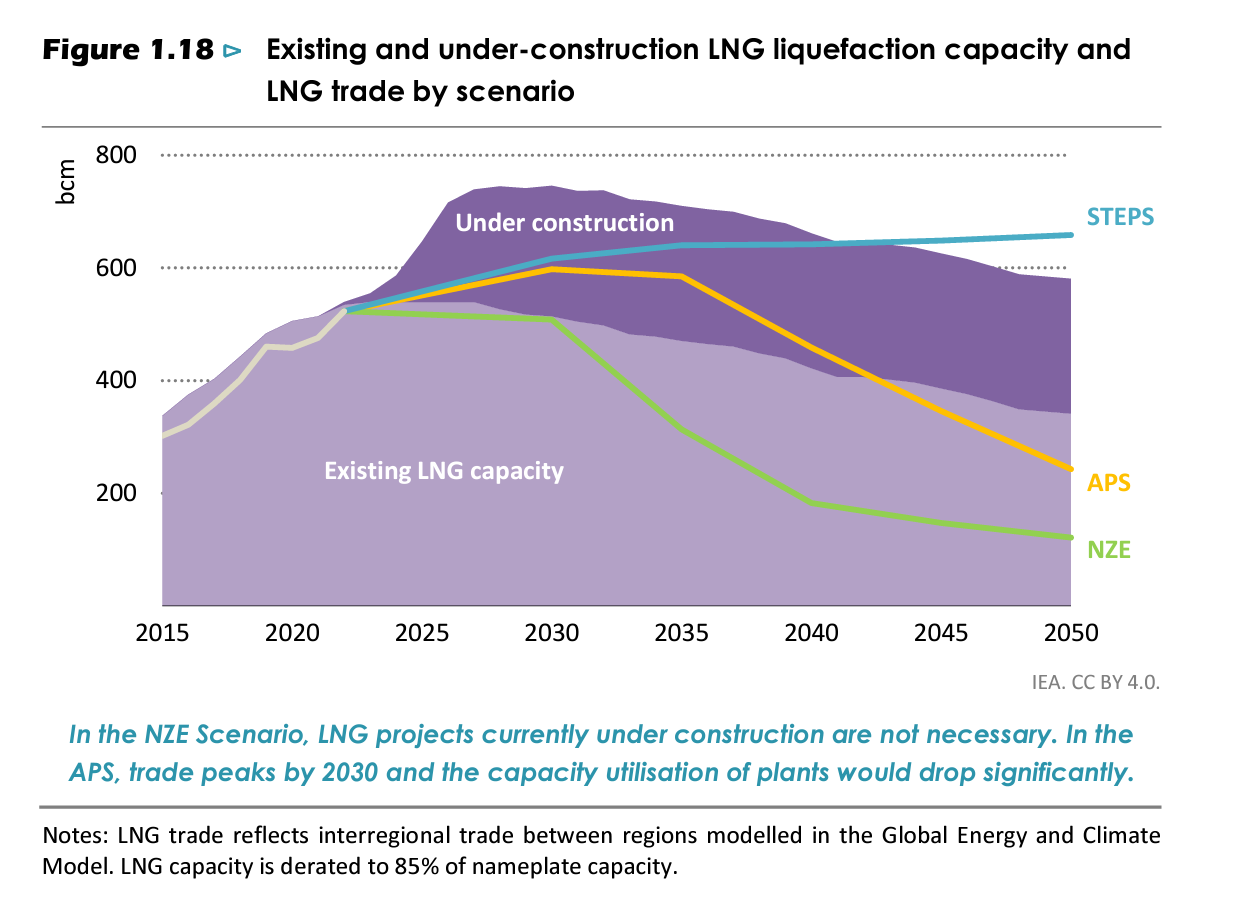

The same uneven contraction will likely play out in the global gas industry with the over-expanded North American industry suffering a huge reduction. Assuming either the implementation of announced climate and energy policies or a net zero path, there will be very considerable excess capacity in LNG at the latest by the mid 2030s, likely sooner.

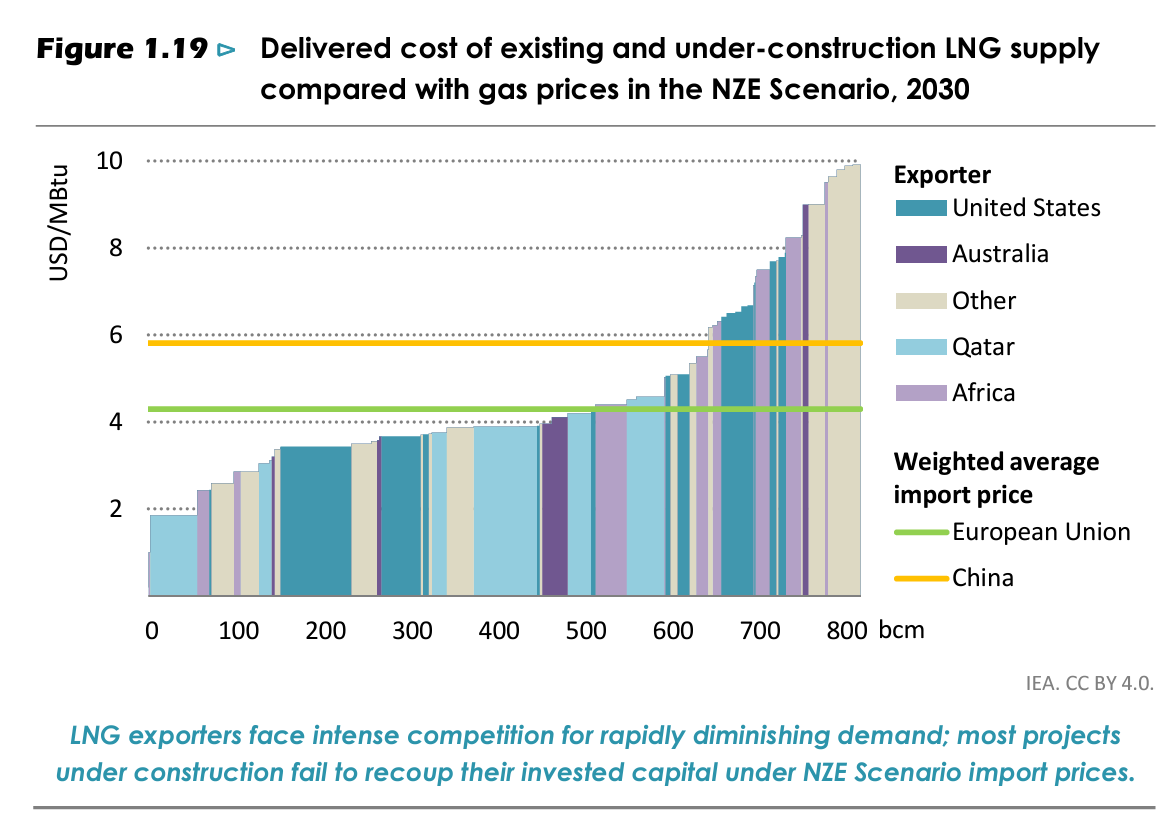

The projects that will hurt the most are the rash of recently announced new LNG capacity, notably in Africa. Their cost base is well above the prices that the IEA expects for LNG by the 2030s. As the IEA demonstrates, low-income high-cost producers like Mozambique in gas or Angola and Nigeria in oil, have a future as major fossil fuel producers, only if they are accorded special preference in the process of contraction.

The case against developing the gas projects currently under discussion in Africa is not principally to do with their climate impact. If they were all put fully into production, the IEA estimates that they would raise Africa’s share of cumulative emissions from 3 % of the historic total to 3.5%. The case against these projects is that against the backdrop of the global exit from fossil fuels they are uneconomic and will become a significant burden for the national governments that back them.

This is the future scenario that the oil and gas industry with their $800 billion annual investment are refusing to face. These are not the imaginings of utopian green activists, but the announced policies of national governments around the world and the best guess as to what needs to be done to achieve climate stabilization. Whether we hit the goal of net zero or not, there is little doubt that demand for oil and gas is going to plunge and the industry is not adjusting to that simple fact.

There may be a future for the capital and expertise commanded by oil and gas firms in the clean energy technologies of the future, notably in “hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels; carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS); offshore wind; liquid biofuels; biomethane; and geothermal energy.” But money talks. If they are serious about those alternatives, investment by the oil and gas industry in clean energy needs to rise from around USD 20 billion in 2022, or some 2.5% of sectoral capital spending, to 50% of capital expenditures by 2030 i.e. to hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

As the IEA makes clear, those companies that choose not to participate in the transition, need to break with the assumption of “business as usual” and start winding down their oil and gas activities paying out dividends and allowing shareholders to reallocate capital elsewhere.

One scenario that the fossil fuel industry should not comfort itself with, according to the IEA, is the idea that gigantic carbon capture will permit a continuation or even expansion of the current industry.

If oil and natural gas consumption were to evolve as projected under today’s policy settings, this would require an inconceivable 32 billion tonnes of carbon captured for utilisation or storage by 2050, including 23 billion tonnes via direct air capture to limit the temperature rise to 1.5 °C. The necessary carbon capture technologies would require 26 000 terawatt hours of electricity generation to operate in 2050, which is more than global electricity demand in 2022. And it would require over USD 3.5 trillion in annual investments all the way from today through to mid-century, which is an amount equal to the entire industry’s annual average revenue in recent years.

Given the industry’s heavy reliance on carbon capture fantasies, this is a strong and important statement from the IEA.

Overall the IEA sketches a picture of a “volatile and bumpy ride.” And this will be more consequential given the ongoing shift in the balance of the world economy and energy consumption: “The implications of any physical disruptions to supply are felt most strongly in emerging and developing economies in Asia, whose share of global crude oil imports rises from 40% today to 60% in 2050 in a scenario that meets national energy and climate goals. On the supply side, even as overall demand falls back, the Middle East plays an outsize role in global markets as a low-cost producer of both oil and gas.”

All in all the IEA report should be seen as a wake up call to the entire industry outside the Middle Eastern core. Supplying Asia’s continued growth will provide future markets for the lowest cost Middle Eastern producers. But what is the future for the swath of independent firms pouring hundreds of billions of dollars into new capacity outside that core Mid East-Asia axis?

The timing of the report is not accidental with the UAE hosting CO28 and the chair of its national oil corporation, Ahmed Al Jaber, serving as the first CEO to preside over the global climate conference. No doubt there will be bold claims of partnership with the private sector. The IEA’s useful report exposes the fantasy that the oil and gas industry are playing a major role in the transition to date and they give us benchmarks by which to assess developments over coming years.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

There is no pathway to reduction in petroleum combustion. Indeed any prosperity that accrues to any society results in bigger cars and more energy consumption. Going green without fossil fuels would require massive investment in nuclear energy , which is not happening. Going green means vast new infrastructure, such as rail , again, not happening. Just a simple improvement in mileage standards in the USA would reduce gasoline consumption, but that easy policy is NOT happening. Planting trillions of trees would help blunt the problem, NOT HAPPENING. The fault is not oil companies, it is the lack of policy from governments big and small to blame.

The IEA’s message is utter nonsense.