In recent years the politics of the climate crisis has changed shape. From a politics of distributing costs, it has morphed into the political economy of the energy transition - an industrial, economic and geopolitical race that is being driven by powerful policy interventions and a broad-based flow of investment and innovation. Leadership in the green energy race is now a prized objective of governments around the world.

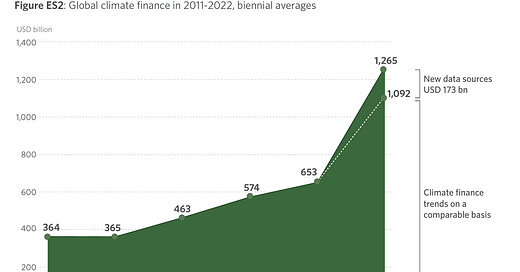

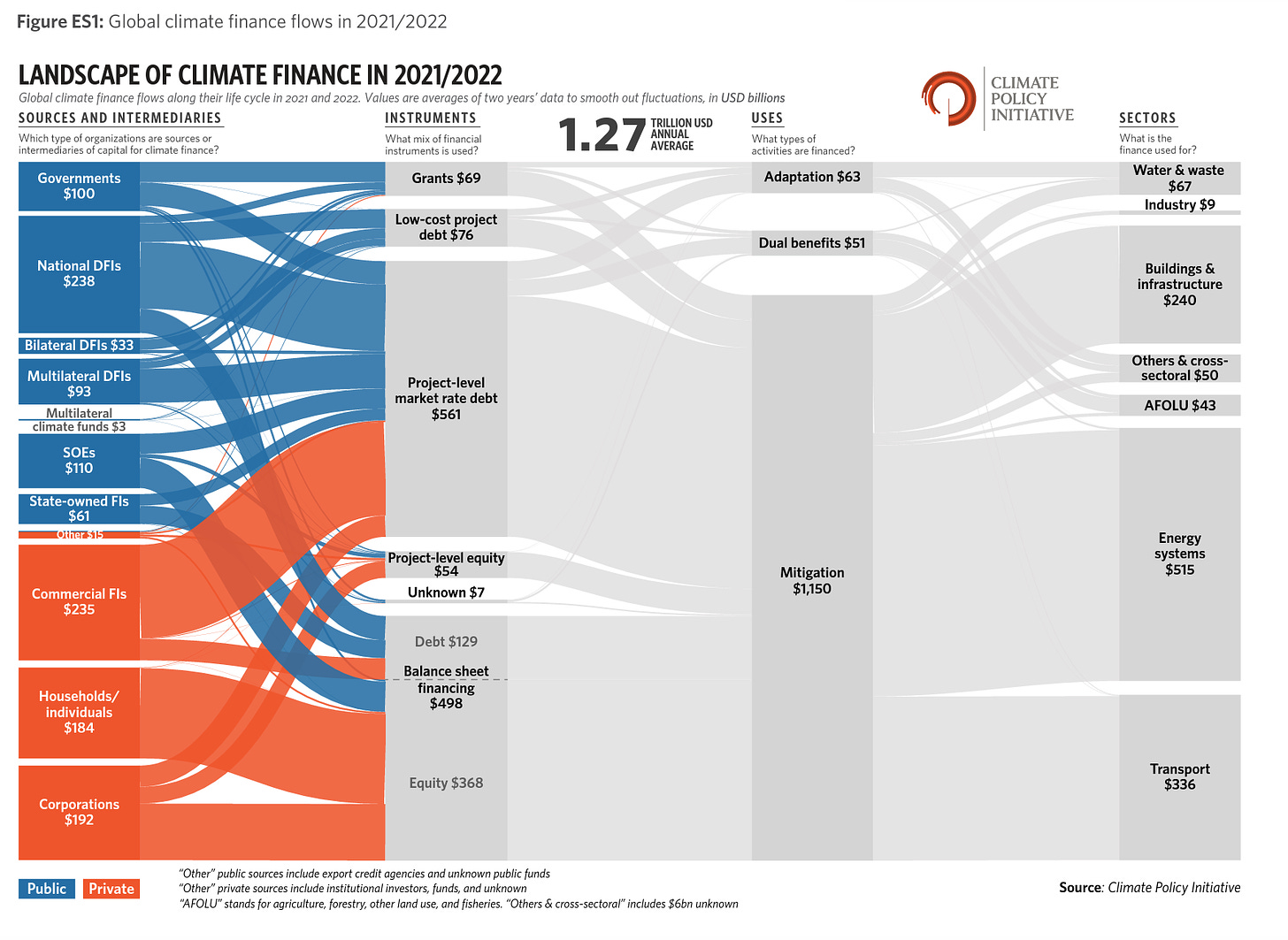

As data released by the Climate Policy Initiative show, between 2019/2020 and 2021/22 the pace of global energy transition investment doubled.

Source: CPI

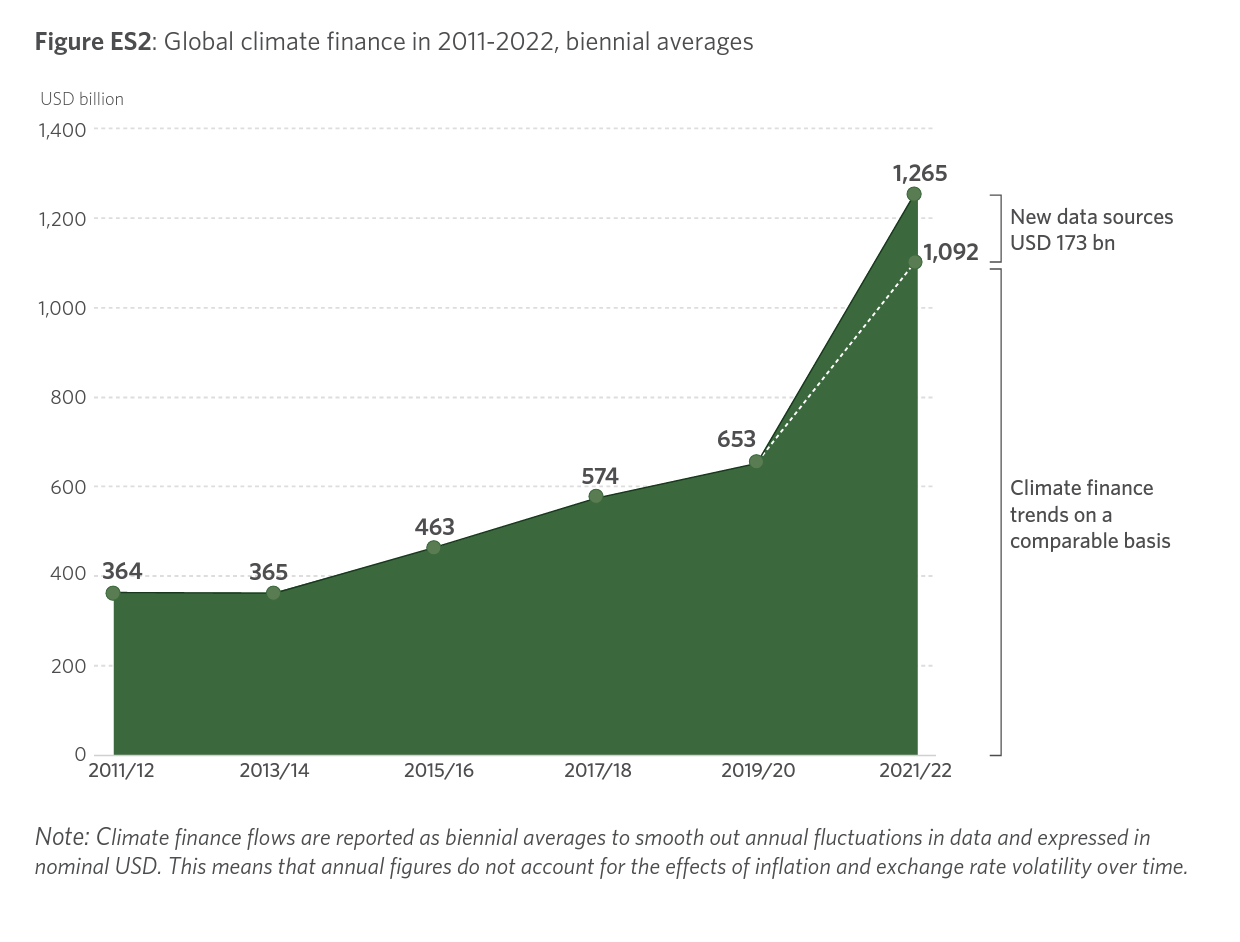

Roughly half of the financial flow is coming from the “private” sector i.e. households, businesses, banks and other financial institutions. The rest is coming from a patchwork of government funds, development finance institutions and state-owned enterprises. In some areas, notably in electricity generation, green solutions are now the commercially optimal, low-cost option. But a large share of the private spending is induced by policy, whether through tax breaks, subsidies or de-risking. The political economy of the actually existing energy-transition is very much a mixed-economy model.

Source: CPI

Energy systems are taking the lions share of all spending, half a trillion dollars in 2021/2022. A large part of household spending is going into the purchase of electric vehicles (EV) whose sales have doubled worldwide. Adaptation receives a strikingly small share of spending.

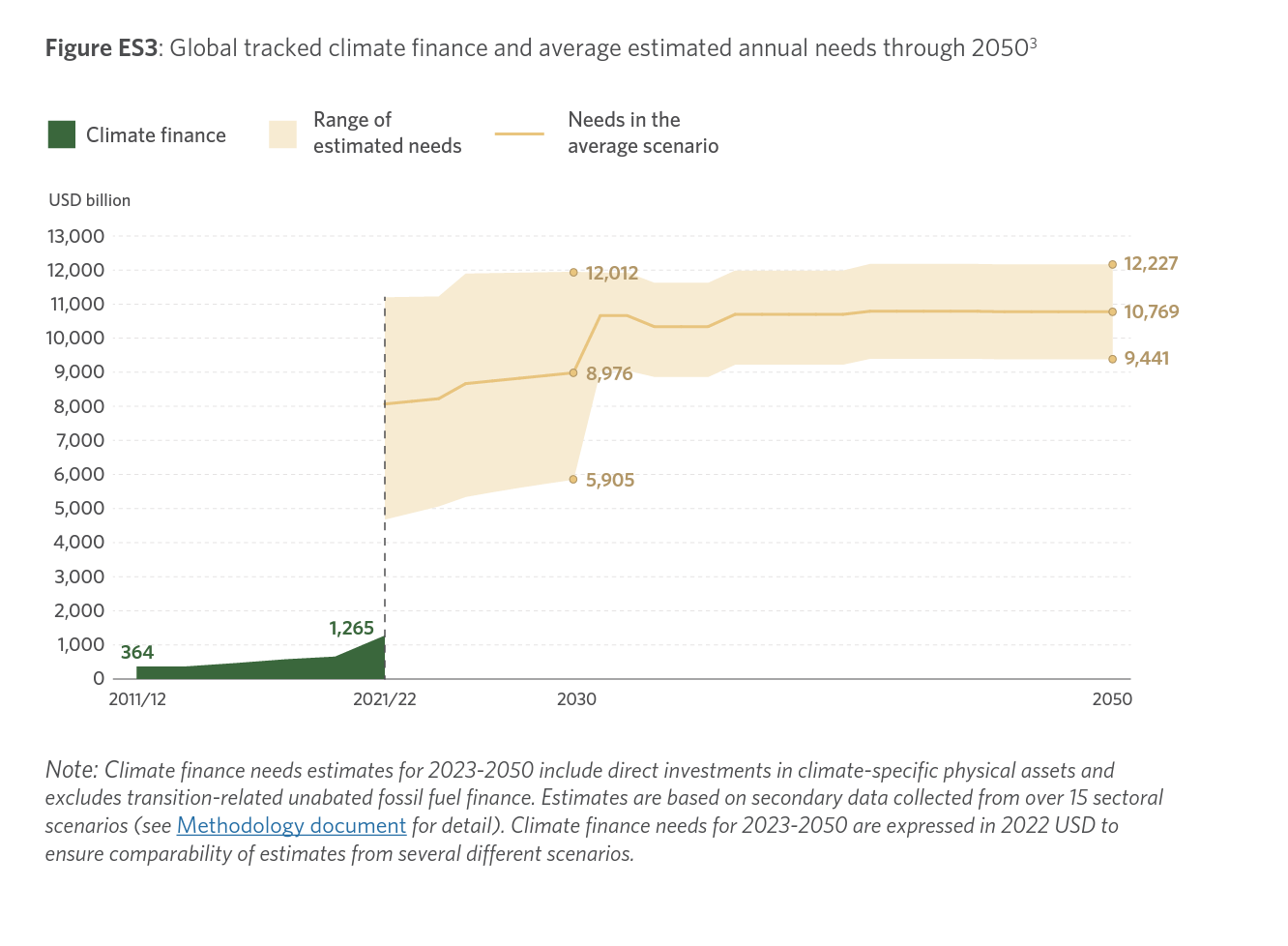

That is the good news. The bad news is that it is conventional logics of political economy that are driving this structural change, not the urgency of the climate crisis. Despite the step up in spending, total investment worldwide is nowhere near large enough to give us a reasonable chance of climate stabilization with moderate temperature increases. Estimates vary, but even on the most optimistic figures, the accelerated spending of 2021/2 was one fifth of what is needed.

There is much talk in policy circles of the race to lead the green energy future. But the pace of the energy transition varies considerably across the world.

The energy transition is hitherto tracking the established map of economic power and financial strength, but doing so very unevenly.

As the CPI report notes, “less than 3% of the global total (USD 30 billion) went to or within least developed countries (LDCs), while 15% went to or within EMDEs excluding China. The ten countries most affected by climate change between 2000 and 2019 received just USD 23 billion, less than 2% of total climate finance.”

At 14 percent, the US and Canada share of energy transition spending in 2021/2022 is substantial. But it is somewhat below Canada and the US share of current emissions and well below their share of historic emissions and global GDP.

Western European spending on the energy transition, at 26 percent of the global total in 2021/2, was more than three times the region’s share of current emissions and somewhat above their share of accumulated emissions and global GDP.

The CPI data do not break out China in detail. But, in passing, the report notes that “China’s domestic climate finance mobilization was greater than that of all other countries combined, accounting for 51% of all domestic climate finance globally.” Even without greater detail, we can therefore conclude that at least as far as domestic resource mobilization is concerned, China’s spending exceeds its one third share of global green house emissions, is, perhaps, three times greater than its share of historic emissions and twice its share of global GDP.

Clearly, in 2021/2022 it was investment in Europe and China that was driving the global energy transition. The Biden administration’s ambition to reclaim “leadership” for the United States in the energy transition must be judged against this baseline. The question is whether it will substantially shift the balance of global investment.

If we look at a recent report by Carbon Brief, which covers more recent spending figures, it becomes clear that even matching China’s pace of investment, let alone shifting the balance to the West will be a tall order.

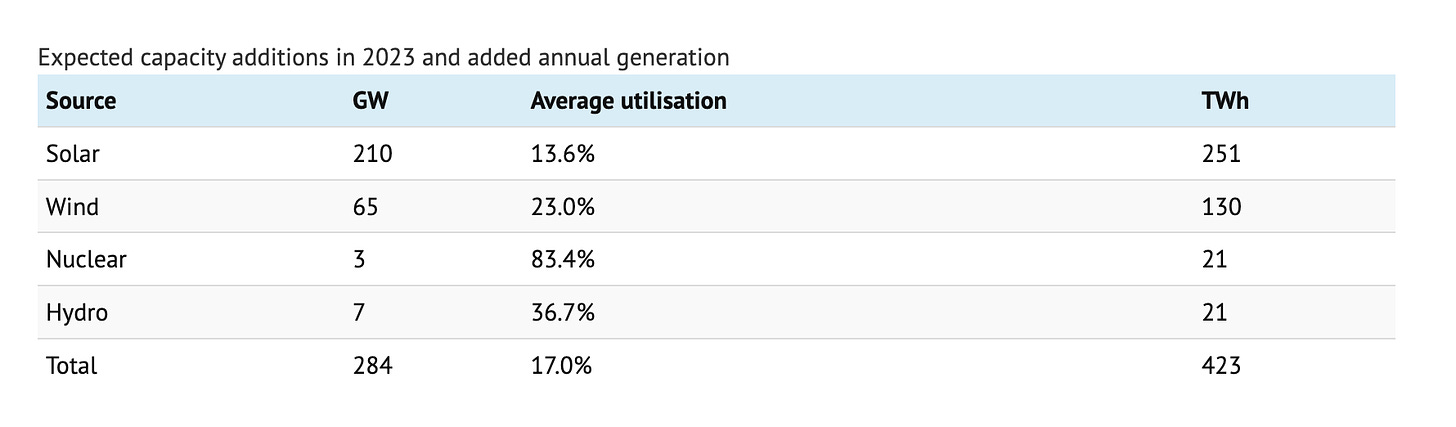

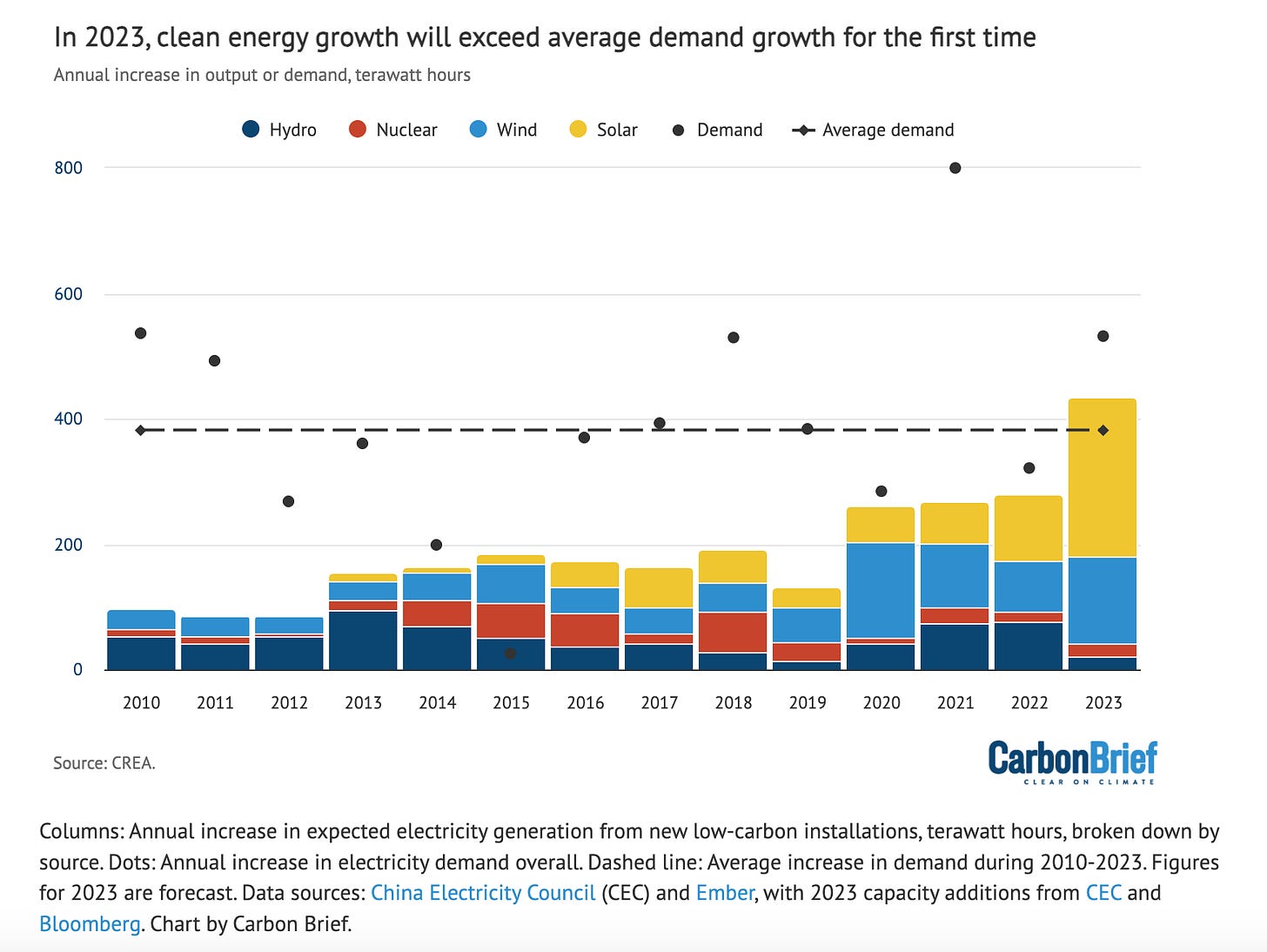

The volume of solar power installation expected in China in 2023 – some 210 gigawatts (GW) – is twice the total installed capacity of solar power in the US and four times what China added in 2020. Allowing for varying utilization rates, China’s low carbon power investment in 2023 will “generate an estimated 423 terawatt hours (TWh) per year, equal to the total electricity consumption of France.”

The implication of these numbers, especially when they are combined with a recovery in hydropower generation, is dramatic.

In 2024, for the first time, net new additions of low-carbon electricity generation will likely exceed energy demand growth, meaning that China’s reliance on fossil fuels for power generation will decline. As Carbon Brief notes:

rapid electrification has meant that almost all of the recent growth in China’s CO2 emissions has taken place in the power sector. Therefore, when power-sector emissions peak, total emissions are likely to follow, as falling coal use outside the power sector balances out increases in oil and possibly gas demand, which are also mitigated by electrification.

Calling a peak in emissions is tricky, but China may actually be getting close. Nothing matters more for the global climate equation. China alone is responsible for one third of total GHG emissions.

China success in driving this extraordinary pace of investment relies on a combination of centralized and decentralized mechanisms.

About half of the solar panels added this year will be installed on rooftops, largely driven by China’s “whole county solar” model, where a single auction is carried out to cover a targeted share of the rooftops in a county with solar panels in one fell swoop.

Under this model, the developer negotiates with building owners and arranges contracts with the grid, financing, procurement, contracting and installations. This model – which could be described as centralised development of distributed solar – has enabled rooftop solar deployment at a vast scale.

The other half of solar installations are set to be in large utility-scale developments, particularly in the gigawatt-scale “clean energy bases” in western and northern China.

And if the pace of new low-carbon capacity installation in China is dramatic, the expansion of the upstream capacity to actually manufacture low-carbon energy technology is even more so.

As Carbon Brief notes:

China’s output of solar cells is set to exceed 600GW this year, up from 375GW last year and enough to produce 500GW of solar panels. For comparison, only 240GW of panels were installed globally last year (2022).

The output of batteries in China will reach 800 gigawatt hours (GWh), up from 550GWh last year and enough to power 20m electric vehicles (EVs).

Electric vehicle output exceeded 8 million units over the 12 months to September, representing more than 30% of all vehicles produced in China. The share of EVs in all vehicles sold in China is also on track to reach 30% in 2023, while production for the calendar year is set to reach 9m vehicles.

This is only the beginning of the industry’s expansion plans. By 2025, solar-panel production capacity is expected to break 1,000GW (1 terawatt, TW), and battery production capacity to reach 3,000GWh.

What has unleashed this extraordinary surge in investment? Carbon Brief is worth quoting at length:

The announcement of the 2060 carbon neutrality target provided the political signal, but wider macroeconomic conditions have delivered low-carbon capacity growth far in excess of policymakers’ targets and expectations, with this year’s solar and wind installation target met by September and the market share of EVs already well ahead of the 20% target for 2025.

The clampdown on the highly leveraged real-estate sector, starting in 2020, led to a steep drop in the demand for land, commodities, labour and credit for apartments and associated infrastructure. This left a hole in the finances of local governments – which rely on land sales for a lot of their revenue – and hit economic growth rates.

Local governments were, thus, searching for alternative investment opportunities to drive economic growth. Yet, at the same time, their investment spending was under scrutiny due to debt concerns. China’s high-level environmental and industrial policy goals made cleantech one of the acceptable sectors for their investment.

At the same time, the government made it easier for private-sector companies to raise money on the financial markets and from banks, as part of measures to stimulate the economy during the pandemic.

The low-carbon energy sector, in contrast with the fossil fuel and traditional heavy industries, is largely made up of private companies. Access to credit had earlier been a major bottleneck for them in a financial system that has heavily favoured state-owned firms.

As a result, much of the bank lending and investment that previously went into real estate is now flowing to manufacturing – largely cleantech manufacturing – as well as to cleantech deployment.

Local government enthusiasm for attracting investments to their regions meant that they often also offered major direct or indirect subsidies. Reportedly, it is common for local governments to build an entire factory and associated infrastructure, with the private company going on to occupy the site only covering the cost of machinery and operations.

All of this happened at a time when falling costs driven by technological learning and subsidies resulted in many low-carbon energy technologies becoming economically competitive against fossil fuels.

China’s policymakers had favoured “green” investments previously, as in the 2009 stimulus package launched in response to the global financial crisis. Yet the sector had been too small to absorb the huge amount of credit mobilised as a part of China’s stimulus cycles. After experiencing extremely rapid growth since 2020, this has changed.

The construction of low-carbon energy manufacturing capacity, production of low-carbon energy equipment and construction of railways have been significant drivers of commodity demand this year, as the only areas of investment showing substantial growth.

This demand explains, among other things, why China’s steel output has continued to grow despite the ongoing contraction in real-estate construction.

Conversely, the precipitous drop in demand for commodities from the real estate and conventional infrastructure sectors explains why the breakneck expansion of low-carbon energy sectors – and their commodity demand – has not resulted in a spike in prices.

The coincidence of the real estate collapse since 2021 and the green energy boom means that China has become the first large economy in which the green energy transition is driving growth at the macroeconomic scale. In the medium-term this must irrevocably change its political economy, with green energy interests coming to the fore. So large is the shift in China that talk of being in mid-transition (Grubert, Hastings-Simon) does not seem far-fetched. But, as Carbon Brief notes, the major test is still to come.

the wave of manufacturing investment has resulted in significant overcapacity in the production of solar panels, batteries and EVs, among others, though the scale of this excess depends on the pace of the global energy transition.

This overcapacity is likely to be resolved – as in previous rounds of expansion – through consolidations and outright failures of individual players. Meanwhile, however, it will continue to depress the prices of low-carbon energy equipment.

Politically, the major challenge will only come when low-carbon energy begins to substantially cut into the demand for coal and coal-fired power.

This shift threatens the interests of the coal industry and local governments with a high exposure to the coal sector. These stakeholders could be expected to resist the transition, raising concerns about potential roadblocks.

When contraction in demand and capacity additions resulted in overcapacity in coal-fired power around 2015, coal power interests successfully argued that low-carbon energy deployment had been too fast.

As a result, the rate of low-carbon energy capacity additions slid down from 2015 until 2019, as seen in the figure above, making more space for excess coal capacity to generate power.

A similar balancing act could come into play once again, as coal and low-carbon generating capacity both continue to expand, competing to meet limited rises in demand.

As Carbon Brief notes, one way for Beijing to strengthen its hand in disciplining its domestic carbon interests would be to raise the ambition of its decarbonization targets. Conceived before the green energy boom took off, these targets still allow for growth in emissions to continue until the end of the decade. Given the pace of the energy transition, China may not need that license to pollute. With its power sector emissions trading system in place, China has the policy tools it needs to cap emissions.

In the hairpin bend that China must perform to achieve net zero, there are bound to be losses. In China this entails questions of the just transition that dwarf those faced in the West. The energy transition puts a further premium on China developing a more generous and flexible welfare state. But, as far as energy and industry are concerned, Beijing’s choice is whether to prioritize the interests of new growing sector of to featherbed a highly polluting coal-based system, whose days are numbered.

***

Thank you for reading this far, if you would like to support the Chartbook Newsletter project through a regular subscription, please click here:

China is going to continue the dirty businesses of mining for coal AND for the rare earths required by supposedly "green" tech. They are brutal realists when it comes to foreign policy and have no real concerns about global warming, other than making sure most of the costs are inflicted on others.

The Chinese government is in the business of maximizing power for the CCP, in this case literally. I don't know how you can be so naive on this. Particularly when you are numerate and every article you write on this topic is about how we aren't going to succeed in limiting global warming, anyway. If the goal we are trying to achieve is impossible, then the people directing us there anyway must have ulterior motives.

For some time I've been worried that the Biden administration's "All of the above" approach (which I believe is also being followed in many countries) means that even though we're making enormous progress in renewables, this won't translate into reductions in fossil-fuel use. So the data from China* is encouraging, but also concerning if their coal industry does have enough clout to strangle renewable development.

*net new additions of low-carbon electricity generation will likely exceed energy demand growth, meaning that China’s reliance on fossil fuels for power generation will decline.