In 2008 Eastern Europe was caught up in the global financial crisis. In 2021 it was hit late by the COVID crisis. In 2022 Eastern Europe is in the frontline of the conflict with Russia over Ukraine.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Eastern Europe and Poland in particular are facing a gigantic refugee flow.

Source: FT

Meanwhile, the shockwaves from sanctions, surging energy prices and a loss of confidence are being felt across the economies of the region.

“You can draw a correlation map between proximity to the conflict areas and market impact,” Kasper Elmgreen, head of equities at Amundi in Dublin, told Katie Martin of the FT.

Poland and the Baltics, in particular, have strong trading and financial ties both to Russia and Ukraine, which put them in the firing line.

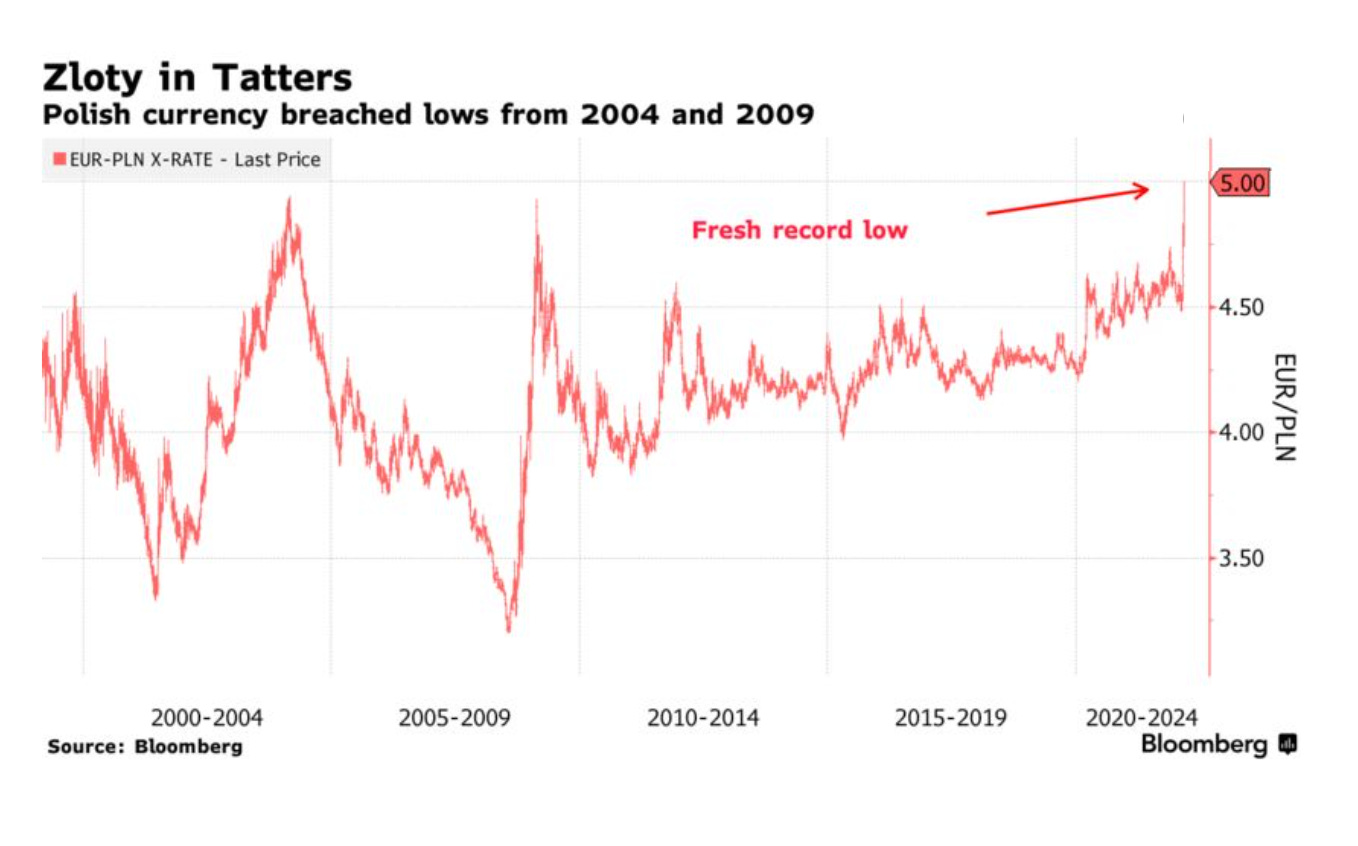

The most visible sign of the stress is to be seen in currency markets. The Polish Zloty has plunged across the psychologically important hurdle of 5 zloty to the euro, a more serious sell off even than during the 2008 crisis.

Source: Bloomberg

In recent weeks there have even been moments of near panic in Poland, which the central bank countered with a blunt assertion of authority. Too much financial news is bad for your grip on reality seems to be the line from central bank boss Glapinski.

Hungary’s forint tumbled as much as 3.2% and came close to 400 against the euro.

Central banks in both Poland and Hungary have taken a robust stance. They point out that the shock depreciation is not consistent with fundamentals. When the war scare has passed, their currencies should, therefore, offer good value to investors. In the mean time the central banks see no reason not to intervene in support if devaluation threatens either price stability or financial stability.

Hungary’s central bank said it was prepared to “intervene with all elements of the toolbox to ensure the stability of the domestic financial markets … The [central bank’s] goal is that the increased risks due to geopolitical conditions do not endanger the price and financial stability of Hungary. Money market movements are not fundamentally justified, but they increase upside inflation risks,” it said.

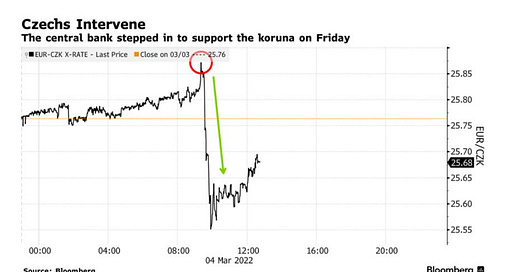

The Czech national bank too has been intervening to support the koruna.

The Czech National Bank defended its measures by arguing that they were “fully in line with the CNB’s previous communications, which emphasised that the central bank is ready to react to excessive exchange rate fluctuations using its instruments in line with the managed float regime”.

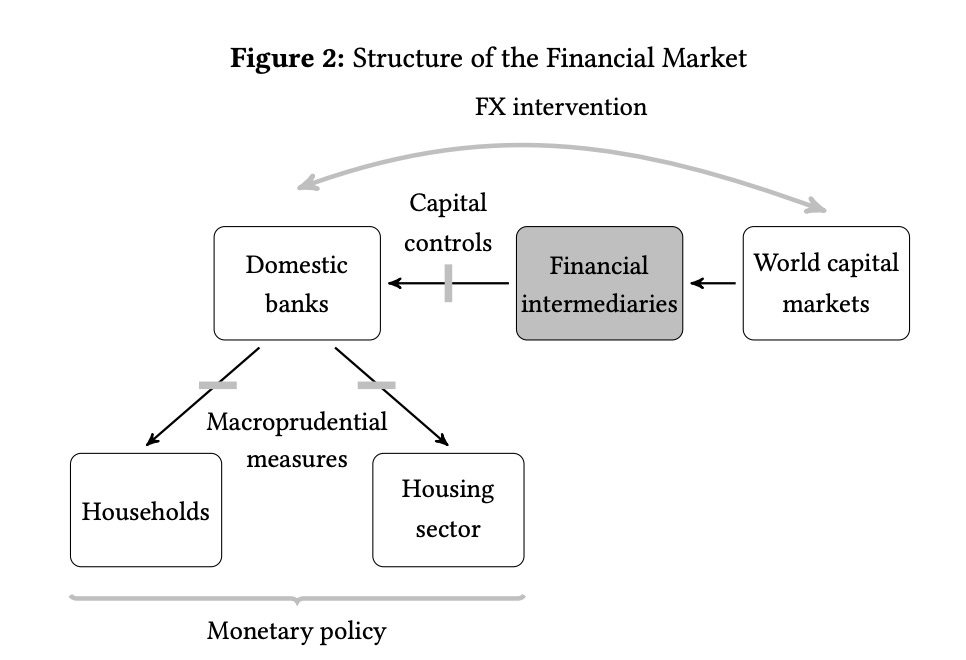

The fact that Hungary’s central bank referred to a “toolkit” is telling.

The East European policy-makers are doing precisely what you would expect competent emerging market policy makers to do under the circumstances. Tactical use of interest rates and foreign exchange interventions backed up by substantial reserves have become the normal way in which emerging markets manage their exposure to global financial risks. As I discussed in Shutdown, the same set of policies were used by EM to meet the financial shock from COVID in the spring of 2020.

Through successive crises the EM have developed a managed model globalization which in the end offers a more functional mix than adherence to doctrinal purity on floating rates and a balance of payments entirely dominated by private flows.

As Claudio Borio of the BIS put it in a speech he gave in June 2019 in managing their monetary policy frameworks, the practice of major EM had moved ahead of theory.

In July 2020 a team at the IMF consisting of Suman Basu, Emine Boz, Gita Gopinath, Francisco Roch, Filiz Unsal proposed to close that gap between theory and practice by offering what they called an A Conceptual Model for the Integrated Policy Framework.

The East European central banks certainly have the resources they need to pursue a stabilization strategy.

As Reuters explains:

The Czech bank has large reserves built up between 2013 and 2017, when it bought foreign currency to keep the crown weak. Reserves amounted to around 66% of gross domestic product at the end of January.

All told the region’s four biggest economies have amassed foreign reserves totaling roughly $430 billion.

Source: Bloomberg

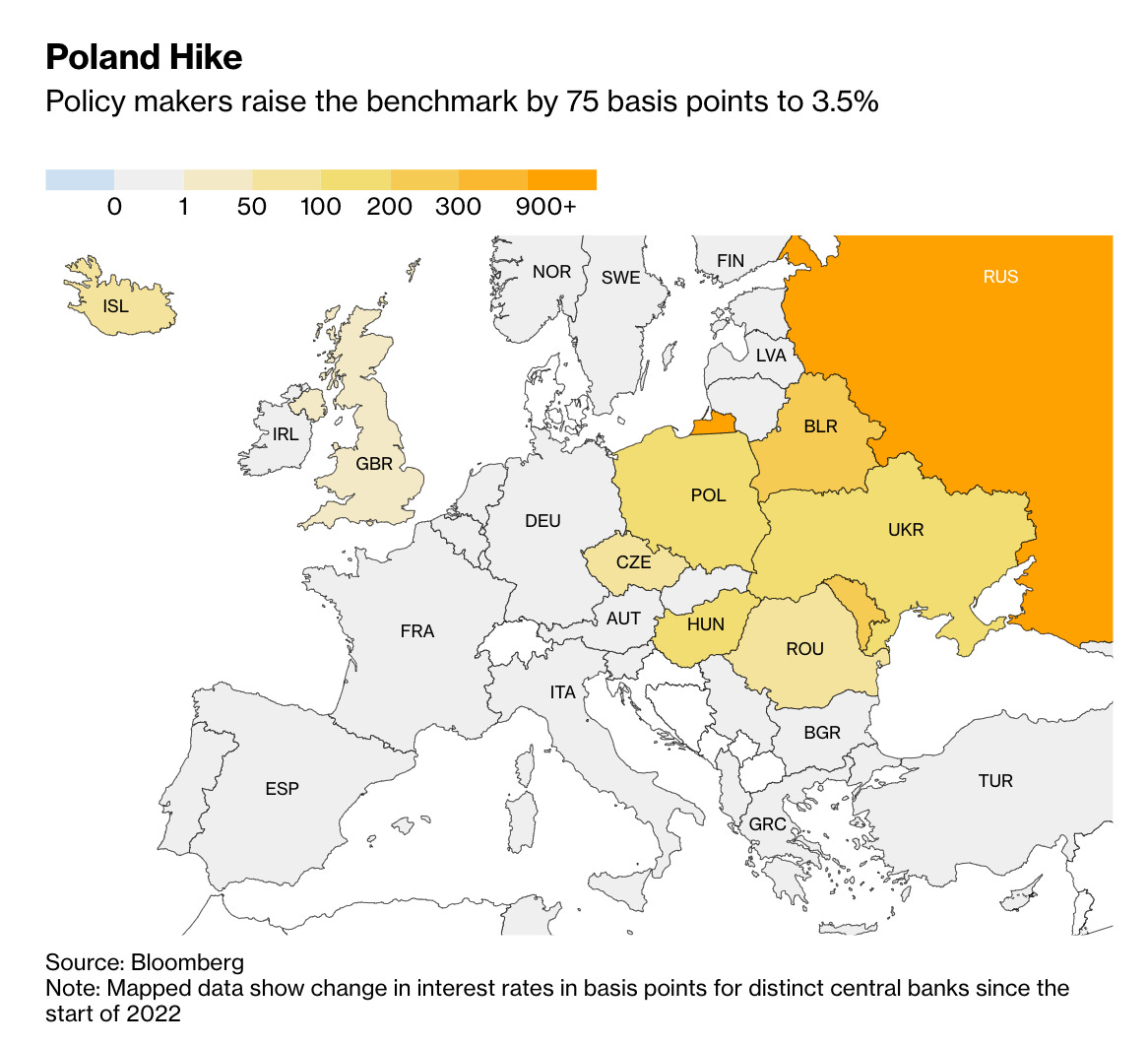

The response of central banks across the region has reflected these reserve positions with Czechia, Poland and Romania intervening in markets and Hungary relying on interest rate increases.

As Jonathan Wheatley reports for the FT,

Hungary’s central bank raised its key policy interest rate by three-quarters of a percentage point on Thursday to 5.35 per cent, a bigger move than expected and the largest since 2008.

Even before the crisis, whilst the ECB argued over its policy response, across Eastern Europe policy-makers were responding to inflationary pressures.

Source: Bloomberg

The Ukraine shock impacts East European economies that were already experiencing more rapid inflation than their West European neighbors. With inflation at 10 percent in the Czech republic, the real interest ahead of the crisis is minus 5 percent. In Poland the gap between inflation of 9 percent and the policy rate of 2.75 ahead of the crisis was even larger.

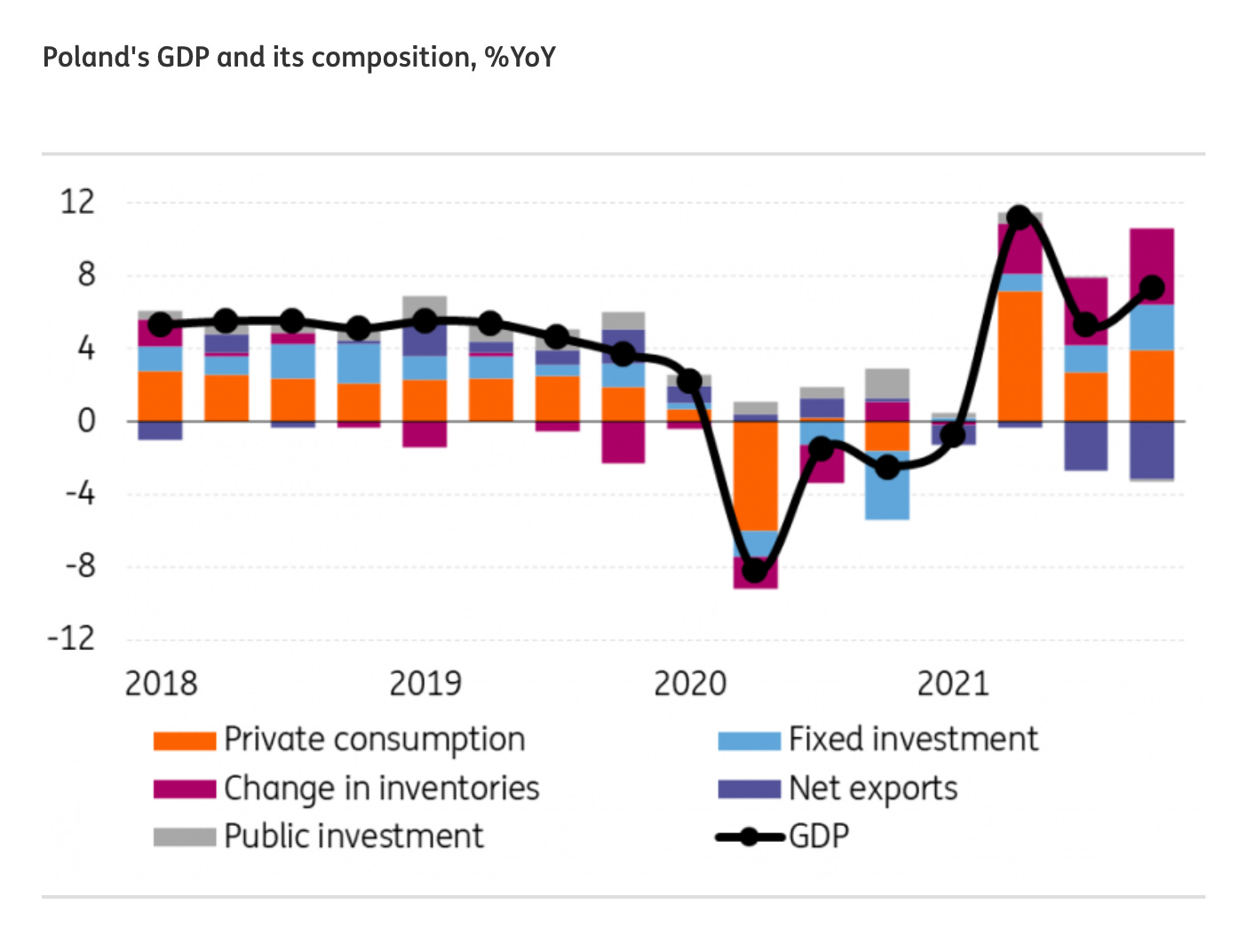

Nor was it merely prices that were growing fast. they were also experiencing a particularly rapid economic rebound from COVID.

ING which publishes excellent research on Eastern Europe cites four risks to Polands economic growth in 2022.

(1) the decline in trade with Russia and Ukraine as well as (2) a general worsening of household and business confidence which will curb spending and domestic demand. Additional downside factors include (3) an energy shock that will further boost commodity prices and undermine purchasing power. Prolonging anti-inflation measures (indirect tax cuts) until December may counteract the increase in crude oil prices to as much as $130 per barrel and a potential hike in natural gas prices by 30% in the second half of 2022. On top of that (4) potential breaks in commodity supplies as a result of military action may also hit the economy, however, the impact is difficult to assess.

All told this leads it to cut its previous GDP growth forecast of 4.5% by 1.3%. .

As Michal Kranz explains in this nice piece for Foreign Policy, Poland has emerged as linchpin of the Western response to Russia’s aggression.

On its Eastern flank the smaller Baltic states are scrambling to adjust to the new situation. At least financially they are better prepared than they would have been four or five years ago when Latvia was rocked by a gigantic Russian money-laundering scandal. As the FT explains:

under heavy pressure from the US and international authorities it embarked on a clean-up of its banks and is now advising other EU countries on how to improve their anti-money-laundering controls. Non-resident deposits — those from outside the country, mostly Russia — have fallen sharply in the past five years.

We should count our blessings that we are not dealing with a gigantic Scandinavian and Baltic banking crisis as a result of the financial sanctions on Russia.

In the event of a financial squeeze the ECB would be the obvious point of call for the East Europeans. The FT in an editorial recommends the provision of swap lines as it did in 2020.

In the short-run the ECB has extended the EUREP emergency facility it set up in 2020 until Jan. 15, 2023. As Bloomberg explains EUREP allows central banks to receive euros in exchange for some euro-denominated debt securities.

EUREP will continue to complement regular euro liquidity-providing arrangements for non-euro area central banks, the ECB said Thursday. These measures form a “comprehensive set of backstop facilities to address possible euro liquidity needs in the event of market dysfunctions outside the euro area that could adversely affect the smooth transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy.” Requests for individual euro liquidity lines will be assessed by the Governing Council on a case-by-case basis, it said. Poland’s central bank said … it was discussing opening foreign-currency swap lines with international counterparts including the ECB, the Federal Reserve and the Swiss National Bank.

One problem that the Polish banking system could urgently do with help with, is, as Bloomberg reports, the immediate financial counterpart to the refugee flow.

Ukrainians struggling to stay afloat in Poland need to swap Ukrainian hryvnia into zloty, most often in quantities of a few hundred euros at a time. Financial markets in Ukraine are closed. In Poland this has led to a huge unbalanced flow of hryvnia into Polish foreign exchange booths and banks, currency for which there is no demand even at massively depreciated rates. As one exchange booth operator told Bloomberg.

“Banks aren’t interested in buying hryvnia from us and it’s not possible to send the currency back to Ukraine safely,” Pawlak, manager of Tavex in Poland, said by phone. “Our reserves are quickly becoming depleted.”

At this moments, markets cannot be a sensible mechanism to value Ukrainian currency and assets. Ultimately this is a political question. How far should Ukrainian refugees be asked to bear the financial consequences of massive devaluation? How far will they be supported by European assistance?

National Bank of Poland Governor Adam Glapinski said on Wednesday that he’s consulting with Ukraine’s central bank, commercial lender PKO Bank Polski SA and its smaller peers to alleviate the problem, calling on the industry to do more.

As far as Poland’s central bank governor Adam Glapinski is concerned, one thing is clear. The war in neighboring Ukraine, may have upended European security and fueled a record weakening of the zloty, but this is not an argument for Poland to join the euro,

Glapinski said on Wednesday that membership in the 19-nation currency area won’t make his country -- the European Union’s biggest economy outside the euro region -- safer in military terms. Joining the euro, however, would lead to slower economic growth and higher inflation, he said, without providing any evidence to support this claim.“We’d lose the opportunity to catch up with richer countries,” Glapinski told reporters in Warsaw on Wednesday. Poles would be reduced to a nation of “asparagus-pickers,” he said, referring to a practice of Polish seasonal workers who travel to Germany to help collect the crop each year.

The comment exemplifies the broader tensions in play. The larger East European states benefit from their attachment to broader institutions of the West, like NATO and the EU, but they do not want to sacrifice any more of their sovereignty than they have to. Indeed, in a dangerous world they see those institutions primarily as supports for their national independence. Russia’s aggression only reinforces that double impulse towards both alliance and independence. It also confirms their broader diagnosis of the threat they face from the East. As Michal Kranz explains in this nice piece for Foreign Policy,

Poland no doubt relishes its new centrality to the Western alliance. At the same time, however, as Glapinski’s comment illustrates, they are also acutely aware of the fact that they could easily find themselves relegated to a subordinate position.

It should not be forgotten that the nationalist government of Poland has provoked an explosive dispute with the EU over basic issues of the rule of law. Or that in 2015/6 Warsaw was resolutely uncooperative with Berlin in its efforts to handle the “Syrian” refugee crisis.

Right now the mood in Europe is still one of solidarity and cooperation, but it could easily tip into something far more ugly.

Interesting to see how Poland's reluctance to join the Euro fits in with their Constituional Court's recent decision that ECHR does not have jurisdiction over recent changes to the judiciary. While there are plenty of economic arguments against joining the Eurozone as set up now, their refusal to integrate in the European juridical system seems a lot less defenseble.

Is anyone thinking about a full-scale realignment of trade? If Russia is permanently pushed out of the WTO (if that's even possible) and if China continues to side with Russia in this continued genocide, can the world readjust trading practices and alliances? Would this open new opportunities, or is it most likely that everyone returns to 'business as usual' until Putin invades yet another sovereign country? I guess I'm asking whether other options, albeit challenging in the short-term) are even possible?