Chartbook #97: Is boycotting Russian energy a realistic strategy? The German case.

How do you weigh the effectiveness of an economic weapon? How do you gauge the likely impact on your antagonist? How do you assess the cost to yourself?

As Nick Mulder has shown us in his powerful new history of the economic weapon, the calculus of sanctions is one of the important domains in which economic and social scientific expertise first came to the fore in 20th-century government.

Today Europe faces the question of how to respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The most obvious way to apply maximum financial pressure to Russia is to stop purchases of oil and gas. Russia’s export earnings are surging. The largest part of that revenue comes from Europe.

Stopping oil and gas purchases would clearly deal a severe blow to Russia. But what would such a boycott cost Europe?

Compared to the suffering of Ukraine the answer, of course, is that the costs will be slight. But no responsible government can avoid taking the costs seriously and weighing the balance. Apart from anything else, if we are in for a long economic war with Russia then we have to ensure that sanctions can be sustained.

Deliberately shutting off a large part of one’s network of energy supplies would be a dramatic demonstration of solidarity with few precedents outside actual wartime. It is the scale of action demanded by climate activists and climate experts, but commonly dismissed as “unrealistic”. The scale and type of economic shock that would be delivered to Europe’s economies - a huge “supply shock” - is most closely paralleled by the actions taken in response to the COVID crisis. As we know from recent memory the pain was intense. The hardship fell unequally on those with low incomes and the measures were highly controversial. We have not yet digested the full impact of COVID. Will Europe’s governments make a second dramatic choice over Ukraine? And how can the costs and benefits be assessed?

Nowhere is this decision weightier than in Germany, Europe’s economic great power. Germany is the key to any European boycott because it buys so much Russian energy. By the same token the impact on the German economy of ending energy imports from Russia is likely to be large. Energy has long been part of German statecraft, a way of exercising leverage and shaping its neighborhood. Will Berlin, faced with the current crisis, deploy the full force of the economic weapon?

The basic facts are clear. Oil accounts for 32 percent of German primary energy input and one third of that comes from Russia. Gas accounts for 27 percent of Germany’s primary energy input, of which 55 percent comes from Russia. Of the coal burned in Germany, which accounts for 18 percent of energy input, 26 percent comes from Russia. All told that means that just over 30 percent of Germany’s primary energy input comes from Russia.

Pipeline gas is the key issue because it cannot be easily substituted by alternative sources of supply.

At the political level, the decision must be agreed between the three parties in the traffic-light coalition, with Chancellor Scholz and Robert Habeck at the Ministry for Economic Affairs and climate playing key roles.

So far the Economics Ministry has taken a cautious position. Habeck has described the consequence for the German economy of boycotting Russian energy as being of the “heaviest proportions” (schwersten Ausmaßes).

That sounds dramatic and the scale of dependence is clearly large. But how do we actually calibrate the likely cost? Only economic expertise can give us any idea as to the orders of magnitude.

The German economics profession, it cannot be repeated too often, is no monolith. It is a world in motion. The problem of an energy boycott is not one that can easily be resolved by reference to familiar positions on inflation, long-term fiscal sustainability etc.

No doubt the analysts in the German economics ministry are burning midnight oil. So far, their calculations have remained behind closed doors. But in the last week the expert debate has spilled into the public sphere.

On March 8 the Leopoldina National Academy of Science published a paper focusing on the technical possibilities of substituting non-Russian sources of energy. They offered a practical to do list of measures with the conclusion that

Even an immediate supply stop of Russian gas could be “handled” by the German economy (handhabbar). There may be shortages in the coming winter, but there are options, through the immediate implementation of a package of measures, to limit the negative effects and to cushion the social impact. .

The authors of the Leopoldina memo were in the main Professors in STEM fields. Economists (Grimm, Schmidt, Wagner … apologies to anyone else I missed) were in a small minority and the memo offered no estimate of the likely costs of the measures they suggested.

The economic question was mapped the same day by a paper co-authored by a distinguished group of economists working both inside and outside Germany.

The team consists of Rüdiger Bachmann: University of Notre Dame, David Baqaee: University of California, Los Angeles; Christian Bayer: Universität Bonn; Moritz Kuhn: Universität Bonn und ECONtribute; Andreas Löschel: Ruhr University Bochum; Benjamin Moll: London School of Economics; Andreas Peichl: ifo Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Universität München; Karen Pittel: ifo Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, Universität München; Moritz Schularick: Sciences Po Paris, Universität Bonn und ECONtribute with research support from Sven Eis.

It is a truly broad church group with no obvious political or institutional alignment in Germany’s spectrum of foundations and think tanks.

Everyone interested should check out the paper. It is technically sophisticated, using a state of the art global trade model, but it is written both in English and German and it is, as far as I am able to judge, comprehensible in its basic logic. We are very much in their debt for the speed and sophistication of this preliminary estimate.

I’ll do my best here to relay some of their key points.

What happens if you cut off Russia as a source of supply depends on whether you can substitute other sources of energy and how far you can economize on energy use.

Bachmann et al take as their main scenario the case in which total gas supplies fall by 30 percent with the result that Germany loses roughly 8 percent of its primary energy supply. What will be the impact on industry, households and the service sector?

To provide a benchmark estimate they start from the multi-sectoral model of trade published by David Baqaee & Emmanuel Farhi in 2019. That model is a very ambitious attempt to model global trade as a set of general equilibrium flows.

The benchmark model has 40 countries as well as a “rest-of-the-world” composite country, each with four factors of production: high-skilled, medium-skilled, lowskilled labor, and capital. Each country has 30 industries each of which produces a single industry good. The model has a nested-CES (constant elasticity of substitution) structure. Each industry produces output by combining its value-added (consisting of the four domestic factors) with intermediate goods (consisting of the 30 goods). The elasticity of substitution across intermediates is θ1, between factors and intermediate inputs is θ2, across different primary factors is θ3, and the elasticity of substitution of household consumption across industries is θ0. When a producer or the household in country c purchases inputs from industry j, it consumes a CES aggregate of goods from this industry sourced from various countries with elasticity of substitution εj + 1. We use data from the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) (see Timmer et al., 2015) to calibrate the CES share parameters to match expenditure shares in the year 2008.33

One of the striking conclusions from the model is that the gains from trade may be much larger than is suggested by many standard models.

For example, for the US, the gains from trade increase from 4.5% to 9% once we account for intermediates with a loglinear network, but they increase further to 13% once we account for realistic complementarities in production. The numbers are even more dramatic for more open economies, for example, the gains from trade for Mexico go from 11% in the model without intermediates, to 16% in the model with a loglinear network, to 44.5% in the model with a non-loglinear network.

This is important for the Russia sanctions debate because many trade models generate very modest gains from trade and correspondingly small effects from any interruption to trade. Indeed, if I read the Baqaee and Farhi paper correctly, it would also allows us to assess the impact of sanctions on Russia. I hope someone will soon perform the same kind of calculation that Bachmann et al have performed for Germany for the Russian side.

In choosing the Baqaee and Farhi model as their workhorse, Bachmann et al presumably hope to ensure that they capture the full effect of any trade interruption. Nevertheless, the results, in all scenarios, are surprisingly modest.

The workings of the Baqaee-Farhi model are very complicated, but the basic intuition is easy enough to follow.

Energy is vital but it does not make up a huge share of expenditure (GNE, Gross National Expenditure). The only scenario in which an energy shock causes catastrophic damage is one in which there is literally no way of substituting or switching economic activities impacted by the loss of energy supply. This would be the case if the basic parameters of production are unalterably fixed - the so-called Leontief case. Taken at face value, that scenario would yield implausibly dramatic results.

As soon as one assumes even a very small degree of substitutability, the effect of the energy supply shock is much more muted. According to the calculations by Bachmann et al, even in a worst case scenario the impact on GDP would come to 3 percent, which is less than the 4 percent shock that the German economy suffered in the COVID crisis.

As Bachmann et al remark

Purely in the spirit of being conservative, we therefore postulate a worst-case scenario that doubles the number without input-output linkages from 1.5% to 3% or €1,200 per year per German citizen. This number is an order of magnitude higher than the 0.2-0.3% or €80-120 implied by the Baqaee-Farhi model. We should emphasize that this is an extreme scenario and we consider economic losses as predicted by the Baqaee-Farhi model to be the more likely outcome

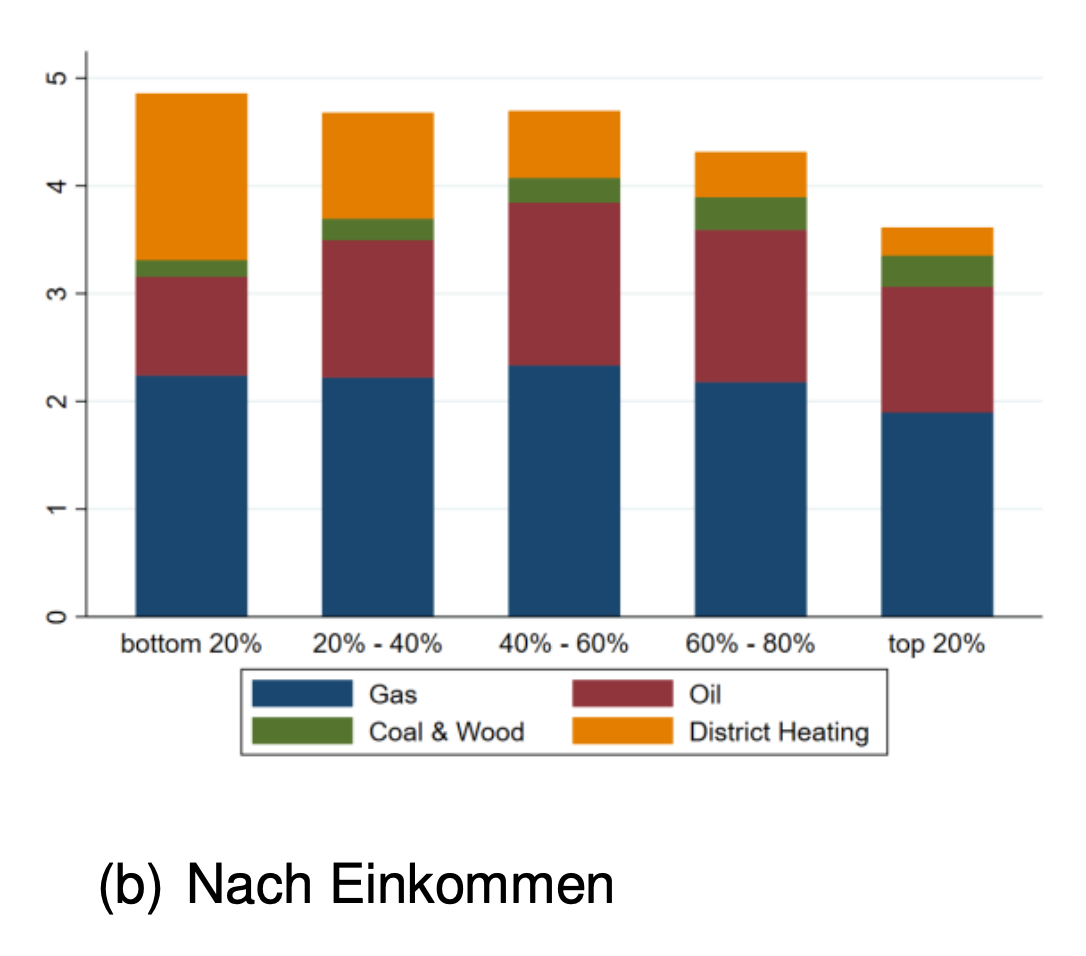

Bachmann et al also provide some pointers as to the distributional impact of any measures. As a share of income, heating and fuel costs do vary by income but not by as much as one might anticipate.

A severe spike in gas and oil prices is likely to cause serious hardship only at the bottom end of the income pyramid, where support should be targeted.

The Bachmann et al paper refrained from declaring the measures “manageable”, as the Leopoldina paper had done. But the scale of the losses they calculated certainly suggested that if sanctions were politically necessary they would be economically feasible. They recommended a cost mitigation strategy that cushioned low income consumers, but otherwise allowed the surge in energy prices to drive the search for energy efficiency. They also recommended that if sanctions were to be applied, they should be applied as soon as possible, so as to enable households and businesses to begin adaptation well before the fall and winter of 2022-2023, when supply difficulties will become most severe.

Taken together the Leopoldina and Bachmann et al papers tended to increase the pressure for action. If alternatives to Russian oil and gas were technological feasible and the economic cost was no more than a few percentage points of GDP, the onus was on the politicians to make the choice. Was it not time for Germany to be brave?

When he was asked about the Bachmann et al study Minister Habeck responded that his Ministry estimated the likely impact of sanctions as far more serious.

But how much more serious? The answer Habeck gave to journalists was a contraction of 5 percent. The significance of that figure is that it was worse than COVID.

Where did it come from?

In the days that followed the Leopoldina and Bachmann et al papers, other experts pushed back, expressing caution and even out-right skepticism about the estimates provided by their colleagues.

Michael Hüther Director of the business-backed private research center Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft in Cologne took issue vociferously with the conclusions of the Leopoldina report. Declaring that a certain policy was “manageable” was a matter of value judgement Hüther insisted.

Later in the week two analysts from the Institute - Thilo Schäfer and Malte Küper - published a comment rebutting the idea that a gas and price stop was manageable. They insisted that it would involve “incalculable risks” and the certainty of a severe price shock with damaging effects for industry.

But “incalculable” is not the same as 5 percent.

It was not just the Leopoldina report that was coming under fire. As reported by Handelsblatt, the Bachmann et al paper was criticized in a confidential paper for the Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate authored by Tom Krebs and Sebastian Dullien. Whereas the Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft was business-aligned, Krebs and Dullien are aligned with the SPD and the trade union movement. When Olaf Scholz headed the Finance Ministry, Krebs took leave from his chair at Mannheim University to serve as a visiting professor. In April 2019 Dullien succeeded Gustav Horn as scientific Director of the Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung (IMK) the macro think tank of the Hans Böckler Foundation of the German trade union movement.

In a paper presented to Habeck’s Ministry Dullien and Krebs apparently argued that Bachmann et al underestimated the likely impact of the shock. According to their calculations they thought a contraction of 4-5 percent of GDP more likely.

As Ben Moll one of the co-authors of the Bachmann et al paper pointed out, Krebs and Dullien did not offer a model to support their estimate. And, as Moll put it, “it takes a model to beat a model”. In fact, the Dullien and Krebs paper had never been intended for public discussion. It was leaked to the Handelsblatt. The IMK is now racing to run its own simulations to back up the initial estimate.

Meanwhile, Dullien and Krebs found themselves in an unfamiliar alignment with Hüther and the team at the Cologne Institute.

Though the line between the two camps seemed clearly drawn, the striking thing is that the Krebs and Dullien estimate of 4-5 percent was not, in fact, dramatically different from the higher estimate by Bachmann et al.

Given the uncertainties involved in the calculation, the divergence is not significant.

After all, the point of the Bachmann et al paper was not to provide a very precise figure, but to gauge the likelihood of extreme negative outcomes. A 4-5 percent fall in GDP would be higher than their modeling suggested and much higher than any outcome suggested by the Baqaee and Farhi model, but it confirmed their broader conclusion that a catastrophe was unlikely.

As Moll pointed out, Goldman and Sachs analysts had also arrived at a similar conclusion. Germany would be hit hard, but its economy would not suffer anything like a catastrophic shock.

So, if Krebs and Dullien felt they were at odds with Bachmann et al, the difference did not in fact lie in their estimate of the economic outcome to be expected, but in their evaluation, in political, social or other terms, of that outcome.

As Moritz Schularick another co-author of the Bachmann et al paper told Handelsblatt: „The conclusion to be drawn should only be really be completely different, if we were talking about 20 or 30 percent.” That is, unless your premises in political, economic and social terms are different, or if beneath the apparent convergence on a prediction of 3-5 percent in GDP contraction you actually imagine very different realities.

Beyond the immediate protagonists in the four-way exchange, one senses other influential figures in the German economics scene aligning themselves on the question of sanctions. Clemens Füst, who heads the IFO institute in Munich, agreed with Krebs in warning of the possibility of cascade effects which result from single firms in production chains suffering sudden stoppages. If this was to occur on a large-scale the contraction in production would be larger than if the effect impacted evenly across the entire economy.

More speculatively, and somewhat tongue in cheek, what is one to make of the fact that Lars P Feld who advises Christian Lindner at the Finance Ministry tweeted out Nick Mulder’s jaundiced take on the history of sanctions published by The Economist?

If one follows the Bachmann et al line it is tempting to say that the upshot of the economic analysis is that the cost to Germany of a boycott would be significant but not so significant that the idea can be dismissed as entirely unreasonable. Their analysis thus puts the ball back in the court of politics. That was the line taken by the Handelsblatt’s Julian Olk.

But on closer inspection it seems that the separation between economic expertise and political judgement is not that neat. If one believes that the costs are, in fact, “incalculable” then excessively precise estimates of the likely costs will in themselves - regardless of the conclusions reached - tend to encourage an activist bias entailing considerable risks. Secondly, the divergent assessment of the meaning of similar estimates of GDP contraction suggests that GDP is insufficient as a measure to capture what rival camps think is essential about the economy. That may help to explain the caution of those who are closer to industry or labour and have to think through the implications of what a 3, 4 or 5 percent shock would actually mean for individual firms, supply chains and workers. Rather than a matter of bias that should be considered a matter of situated perspective, or standpoint. Closeness to “the interests” of producers reveals things that cannot easily be seen from the vantage point of a global macro model however sophisticated it may be.

Certainly, if Berlin is to decide to go ahead with a boycott, what will be required will be a coalition-building exercise that will need to extend from the broader public, to key interest groups and to the realms of expertise, where the scale of the problem is being measured and assessed. Persuasion, calculation, mobilization and preparation is the work that would make a policy of full-scale sanctions realistic.

***

I love writing Chartbook and I am particularly pleased that it goes out free to thousands of readers all over the world. But it takes a lot of work and what sustains the effort is the support of paying subscribers. If you appreciate the newsletter and can afford a subscription, please hit the button and pick one of the three options.

In “normal times”, when the newsletter is not going out practically every day, paying subscribers receive regular Top Links emails with interesting, entertaining and beautiful reading and viewing. Let us hope for the return of more normal times soon.

In the mean time, please share Chartbook with your friends.

It is tempting to just observe that if you take a set of complex equations and plug in a set of parameters that you (to use a crude expression) "pull out of your **" you can produce whatever numerical output you want, but it may be more productive to just go to the old "forrest" v. "trees" distinction and try to look at first principles.

1. Lets start with the relatively observable fact (as described above) that Russia provides 30% of Germany's primary energy.

2. There either IS "spare capacity" for energy production equal to that 30% or there IS NOT.

3. All analysis of the form discussed above is fundamentally predicated on the assumption that THERE IS such "spare capacity", and then models the cost of re-configuring Europe's (and the World's) energy systems to switch from Russia as the source to that "spare capacity" source (whatever/wherever it is).

4. So, is there?

5. The fact that the US has been begging the Saudis/UAE to increase output yet got no effect, and is now turning to Venezuela suggests that there IS NOT all that much "spare capacity". (The fact that prices are at all time high and any such hypothesized "spare capacity" hasn't moved to take advantage of these high prices supports the thesis that it doesn't exist.) It may be possible to find a few percent (5%?) by ramping up coal, but again, where are all these "ready to go" coal power plants?

6. If that is the case, then any effort by Germany to diversity ITS supply, will involve diverting such energy supplies from someone else.

7. That someone else will now need to substitute for the missing supplies - and if there is no "spare capacity", then the only place they can turn is Russia.

8. So, unless there is a "net decline" in total energy use, the net result of Germany's policies would be be higher prices (due to the need to rearrange how energy is routed) while volumes produced and sold by all suppliers (including Russia) remain the same.

9. Thus, we need to look at the alternative concept - there is no "alternative source", so Germany needs to simply reduce global consumption of energy by that 30% of Germany's energy usage.

10. Given the broad correlation between energy use and "activity" (including economic activity, but really all activity - "Life" is "Energy Use"), for Germany to reduce energy consumption by 30% would represent a massive drop in GDP. It may not be quite 30% because some "efficiency gains" are possible, but it would be close.

11. More importantly, that decline isn't just a "number". It would involve "energy rationing", so choices will need between cutting household heating (leading to people freezing) of shutting down transport and factories (leading to massive unemployment).

12. The alternative is to "spread the pain" across Europe, forcing other EU countries to lower their energy consumption and redirect the savings to Germany.

13. This brings us to the fact that Germany is not the only EU country using Russian energy. (It is worth noting that Russia controlled sources (including Kazakhstan) are also a major supplier of Uranium for Nuclear Reactors - 40% of US purchase, and a fair chuck of France's).

14. While there are "long term" options (Geothermal? Wind? Fusion?) these will not be providing significant amounts of energy in the next 12 months.

Fascinating summary, thank you. I’d like to see some analysis/discussion about the Russian hard currency windfall to due to price escalation. What does this really mean? Is this hard currency that Russia cannot access due to the market constraints put in place by the west? If not, where does it go, how is it spent? Is the war a net financial gain for Russia because of this windfall? Is Russia (and the world) learning that starting a war is a great way to raise profits in energy? I’d like to understand the answers to this line of questions a lot better.