This arresting and mysterious image is one of many captured by Reuters photographers in Ukraine. Check out this amazing gallery

It adorns the mast head of the remarkable tracking project “What the Russia-Ukraine war means for Africa”. Mounted by Africa Policy Research Institute. On trying to get a handle on the impact of the war in Ukraine on Africa, I am also following this fantastic thread by David McNair.

David McNair is ED for global policy at ONE, “a global movement campaigning to end extreme poverty & preventable disease by 2030, so everyone, everywhere can lead a life of dignity and opportunity”.

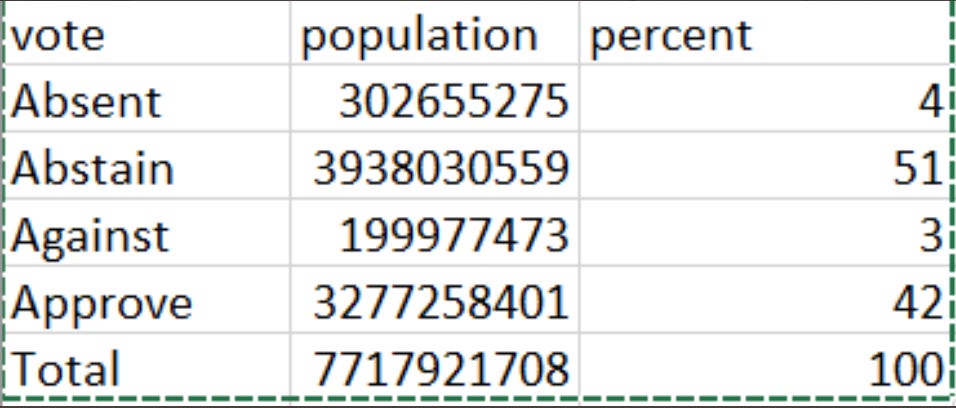

At the UN vote condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on March 2, 141 countries voted in favor, 4 against and 35 abstained. Those numbers are deceptive, however, because of which countries were in each camp. Though the motion to condemn Russia had an overwhelming majority, weighted by population the vote looked different. Of the 7.7 billion people represented by governments taking part in the vote, only 42 percent were from countries approving the motion condemning Russia. Governments representing 51 percent of the world’s population abstained.

Source: David McNair

The group of abstainers was led by China and India, who make up the bulk of these numbers. But half of the 35 states that abstained were African. Syria and Eritrea were in the handful voting with Russia to reject the motion.

Many important African states assertively criticized and condemned Russia’s aggression. In a truly remarkable statement to the UN, Kenya’s ambassador Martin Kimani linked post-colonial African and post-Soviet European experience. It’s a truly remarkable intervention that really ought to teach lessons to Europe.

As Quartz reports:

In a statement to the UN Security Council at an emergency meeting on Feb. 22, Kimani criticized Russia for seemingly prioritizing ethnic self-determination over the pragmatic acceptance of borders. Many of Africa’s borders were created arbitrarily by colonial powers, he pointed out, but most countries chose not to dispute them because of the possibility of years of bloodshed. “Kenya, and almost every African country, was birthed by the ending of empire,” he said. “Our borders were not of our own drawing. They were drawn in the distant colonial metropoles of London, Paris, and Lisbon with no regard for the ancient nations that they cleaved apart.” “Rather than form nations that looked ever backward into history with a dangerous nostalgia, we chose to look forward to a greatness none of our many nations and peoples had ever known,” he continued. “We chose to follow the rules of the OAU [Organization of African Unity] and the United Nations charter, not because our borders satisfied us, but because we wanted something greater forged in peace.”

However, not everyone chose to follow Kenya in condemning Russia’s aggression.

The list of the abstaining countries included South Africa, Senegal, Mozambique, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

The vote is a marker of ties to Russia that go back to the Cold War. In this sense the abstention by Zimbabwe, Mozambique or the ANC-government in South Africa was similar to that of India.

It was not, however, just a matter of Cold War legacies. In the case of India, modern day geopolitics played a key role (India plays Russia against China and Pakistan). And geopolitics played a role in the African votes as well.

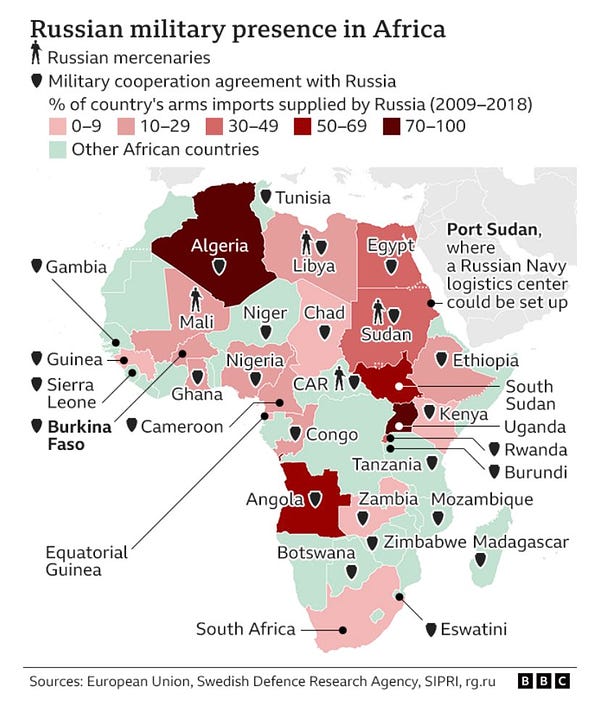

It is hardly surprising, for instance, that Mali should have abstained, given the prominent role that Wagner mercenaries are playing in the effort by the new regime to consolidate power.

South Africa’s position also reflects present day concerns. As Bloomberg reported:

On the day the invasion began, South Africa’s foreign ministry urged Russia to immediately withdraw its forces and respect Ukraine’s territorial integrity. A day later, Ramaphosa took a different tack, saying U.S. President Joe Biden should have agreed to an unconditional meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin to avert war, and called for dialogue.

Kenyan political activist Nanjala Nyaboka said on Twitter. Africa bought almost 50% of its military equipment from Russia in 2015–2019, almost double its weapons imports from the U.S. and China, according to the South African Institute of International Affairs.

Another excellent overview of the geopolitics comes from Nosmot Gbadamosi at Foreign Policy. As she reports:

Russia has been expanding its military support in Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Mozambique with advances in Mali in fighting rebels and jihadist insurgents. The second Russia-Africa summit was scheduled for October to November this year in Addis Ababa. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began, the deputy leader of Sudan’s junta, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemeti” Dagolo, led a delegation to Moscow to strengthen closer ties between the two countries. (Russia has gold mining concessions in Sudan.)

Nigeria voted to condemn Russia, but there too there are worries about investment and trade. Particularly, over the future of the Ajaokuta Steel Complex

which has already cost more than $8bn over the past 40 years. However, the new sanctions Russia is facing in the light of its invasion of Ukraine are putting the project in jeopardy, experts say.

Nigerian experts and lobbyists worry that the decision to vote with the West on the UN motion might jeopardize the latest push to complete a project whose origins go back to the Cold War.

Conceived as the centrepiece of Nigeria’s industrial take-off in 1979, the first phase of the Ajaokuta project was built by Russian firm Technopromexport. The project was expected to have been completed in 1986, but due to policy inconsistencies caused by coups, this target was not met. In 1994, the Russian firm abandoned the project when it was at 98% completion, citing Nigeria’s inability to meet its contractual obligations. In 2001, Russia made moves to complete the complex. In 2004, then president Olusegun Obasanjo picked US firm Solgas Energy to complete it. The government cancelled the contract due to non-performance and subsequently handed it to Global Infrastructure Nigeria Limited (GINL), which is owned by Indian firm Global Steel Holdings.

Having resumed cooperation with the Russians on the steelworks in 2019, Nigeria may now turn to the Chinese.

Mapped like this, the conflict in Ukraine might be framed in terms of the “small world war” paradigm that Georgi Derluguian applied so productively to the Armenia-Azerbeijan war of 2020.. That conflict should not be underestimated as a link in the chain that led to Putin’s assault on Ukraine.

But, it would be reductive to treat the question simply from the point of view of geopolitical influence. It is not just governments and the play of power that are at stake here.

The presence of Africans in the midst of the crisis is striking. Thousands of Africans who were living, working and studying in Ukraine at the start of the war, have been caught up in the vast flow of refugees to the West.

It is a bitter irony that their presence was highlighted precisely by the fact that they were subject to racist exclusion by the border guards of Ukrainian and its neighbors. Otherwise, they would just have been people “like others” fleeing the war. Instead, black refugees were singled out and mistreated for breaking the frame of the unabashedly racist narrative that the refugees from Ukraine were “different” because they were “not from the third world”, were “blond and blue-eyed” and looked “just like us”.

What was lost on this commentary was the further irony that the Africans caught up in the war had not imagined themselves to be “in the Third World” either. The refugees in Ukraine - white and black - are flowing within the “global North”. Once again, Yugoslavia in the 1990s comes to mind. The flows are perhaps analogous structurally - though not in their immediate terror and violence - to those triggered by economic crises in the global North - Mexican return migrant, for example, when the US economy enters a recession.

The black refugees caught on the Ukraine-Poland border were not fleeing for their lives because they had lost their states, but because the Ukrainians were about to lose theirs. The shameful scenes of racism at the border were not inflicted on fleeing people who did not have rights, or the right to have rights. The “ordinary “procedures of racial profiling in legal passage by people of color across interstate borders were overlaid over a deregulated wartime crisis. So severe was the situation, that the diplomats of Ghana, South Africa and Nigeria, amongst others, were forced to intervene on their citizen’s behalf.

This drama was horrible, but it was perhaps to be expected. Racism at Europe’s borders is the norm, after all. What is more surprising is the sheer number of people of color in Ukraine when the war began.

By some counts it was as high as 80,000. Many of those were registered on student visas. The flow of educational migrants from many African states to Ukraine, made up a kind of middle-class migration, through which Africans seeking upward mobility enrolled in Ukraine’s education system … “just like us” in other words.

As the Globe and Mail reports:

tens of thousands of Africans are studying at Ukrainian universities, which many of them see as much more affordable than other foreign universities. There are more than 16,000 students in Ukraine from Nigeria, Morocco and Egypt alone, according to Ukrainian statistics.

As the BBC reports, the students too, not just the loyalty of the ANC and Nigeria’s steelworks, are legacies of Cold War-era globalization.

Ukraine has long appealed to foreign students, which can be traced back to the Soviet era, when there was a lot of investment in higher education and a deliberate attempt to attract students from newly independent African countries. Now, Ukrainian universities are seen as a gateway to the European job market, offering affordable course prices, straightforward visa terms and the possibility of permanent residency. "Ukrainian degrees are widely recognised and offer a high standard of education," said Patrick Esugunum, who works for an organisation that assists West African students wanting to study in Ukraine. "A lot of medical students, in particular, want to go there as they have a good standard for medical facilities," he added.

For the foreign students, the war comes as a catastrophic shock. Will they be able to continue their studies and recoup their investment? Or will a war in the North disrupt their upward mobility?

The war’s effects will also be felt more widely on the continent of Africa itself.

Commodity exporters will do well out of the general surge in commodity prices, triggered by the crisis. Algeria’s oil and gas exporters, for instance, look set to make a killing.

But importers may find themselves in severe difficulty.

This report about Egypt’s food situation from @michaltanchum at MEI, is dramatic.

With the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war on Feb. 24, 2022, Egypt's food security crisis now poses an existential threat to its economy. The fragile state of Egypt's food security stems from the agricultural sector's inability to produce enough cereal grains, especially wheat, and oilseeds to meet even half of the country's domestic demand. Cairo relies on large volumes of heavily subsidized imports to ensure sufficient as well as affordable supplies of bread and vegetable oil for its 105 million citizens. Securing those supplies has led Egypt to become the world's largest importer of wheat and among the world's top 10 importers of sunflower oil. In 2021, Cairo was already facing down food inflation levels not seen since the Arab Spring civil unrest a decade earlier that toppled the government of former President Hosni Mubarak. After eight years of working assiduously to put Egypt's economic house back in order, the government of President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi is now similarly vulnerable to skyrocketing food costs that are reaching budget-breaking levels.

The Russia-Ukraine war catapulted prices to unsustainable levels for Egypt, increasing the price of wheat by an additional 44% and that of sunflower oil by 32% virtually overnight. Even more troublesome, the war also threatens Egypt's physical supply itself since 85% of its wheat comes from Russia and Ukraine, as does 73% of its sunflower oil. With activity at Ukraine's ports at a complete standstill, Egypt already needs to find alternative suppliers. A further escalation that stops all Black Sea exports could also take Russian supplies off the market with catastrophic effect. With about four months of wheat reserves, Egypt can meet the challenge, but to do so, Cairo will need to take immediate and decisive action, which can be made even more effective with the timely support of its American and European partners.

As the Africa Report points out:

Food and transport account for around 57% of the consumer price index in Nigeria, 54% in Ghana, 39% in Egypt and a third in Kenya.

All of them will experience serious inflationary pressure as a result of the surge in energy and food prices. As the Report concludes

Africa has an overwhelming interest in peace in Europe.

And as Kenya’s ambassador Martin Kimani has so brilliantly demonstrated, it may have lessons to teach.

When the EU and African Union hosted a joint summit in mid-February that was no doubt not how the relationship was imagined. The summit was overshadowed by the crisis in Mali that betoken the unraveling of a large part of the West’s position in the Sahel. The result of the summit was another big EU initiative for investment in Africa.

The scale is big. It needs to be far larger. And how much of the 150 billion euro are actually delivered remains to be seen. The fruits of Angela Merkel’s “Marshall Plan With Africa” of 2017 were modest.

In the short-run the more immediate concern is for aid funding. When Europeans are spending their aid budgets on people “just like us”, what will happen to overseas funding? The precedent of the 2015-6 refugee crisis is not encouraging with many countries significantly reallocating aid funds to pay for refugee reception.

That is an arresting image; even more arresting to me is the global population chart representing Abstain. It is a stark reminder that when we say the whole world is against Russia, we misspeak.

I have been following McNair's thread also. Excellent unpacking, AT, of data on African countries voting to abstain and the consequences of the war in Ukraine on food supplies.