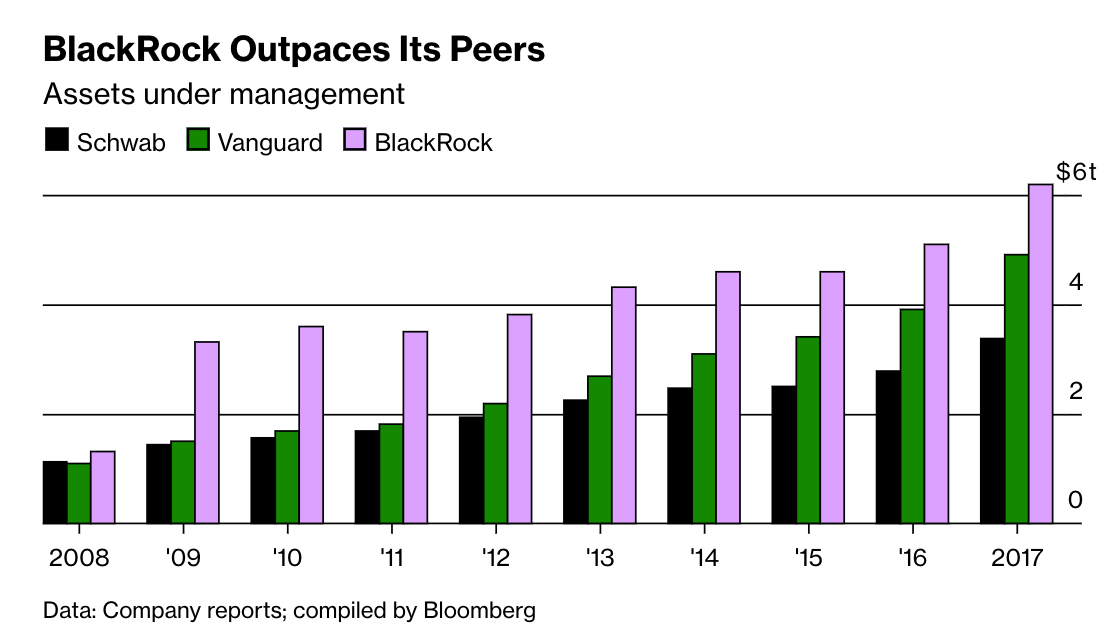

We live in a remarkable world. As of July 20 2021, three asset managers, BlackRock, Vanguard Group and State Street Corp. collectively owned about 22% of the average S&P 500 company, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, up from 13.5% in 2008.

Asset manager capitalism

My friend Prof Mark Blyth (Brown) - who needs no introduction, but is fantastic and an essential follow - gave this great short talk the other day on the theme of asset manager capitalism and inequality. It is, as you would expect highly recommended!

Mark features the work of our brilliant colleague Benjamin Braun. No that’s not a BlackRock exec, that’s Ben looking sharp! (And that’s Mark in the top right-hand corner)

Literally everything that Ben does is fascinating and his twitter account is an endless source of other good things to read. He is a great guide to the current scene in critical studies of finance etc. Here’s the description of Ben’s research on asset manager capitalism with links to two papers.

Financial capital has become abundant in the global economy. The logic of supply and demand would suggest that wealth owners and their financial intermediaries should see their structural power decline. Paradoxically, the ultimate gauge of rentier power – the gap between the rate of return on capital (r) and the rate of economic growth (g) – has proven remarkably resilient since the 1980s. Why did this gap not shrink? The guiding hypothesis of this project is that the power of wealth owners is partly a function of the organization of finance. The project studies the rise of different types of asset managers – firms that pool and manage “other people’s money” – and their impact on the economic and political determinants of the rate of return on capital. American Asset Manager Capitalism [2021] studies the rise of large asset managers in the United States and the consequences for the political economy of corporate governance. From Exit to Control [in progress] argues that the rise of asset manager capitalism means that the primary mechanism underpinning the structural power of finance has shifted from exit to control. However, asset manager capitalism differs from early 20th-century “finance capital” because unlike the banks studied by Hilferding, today’s asset management giants combine control with diversification.

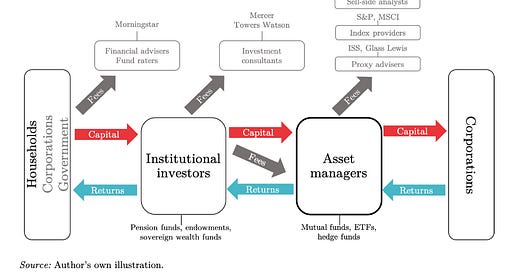

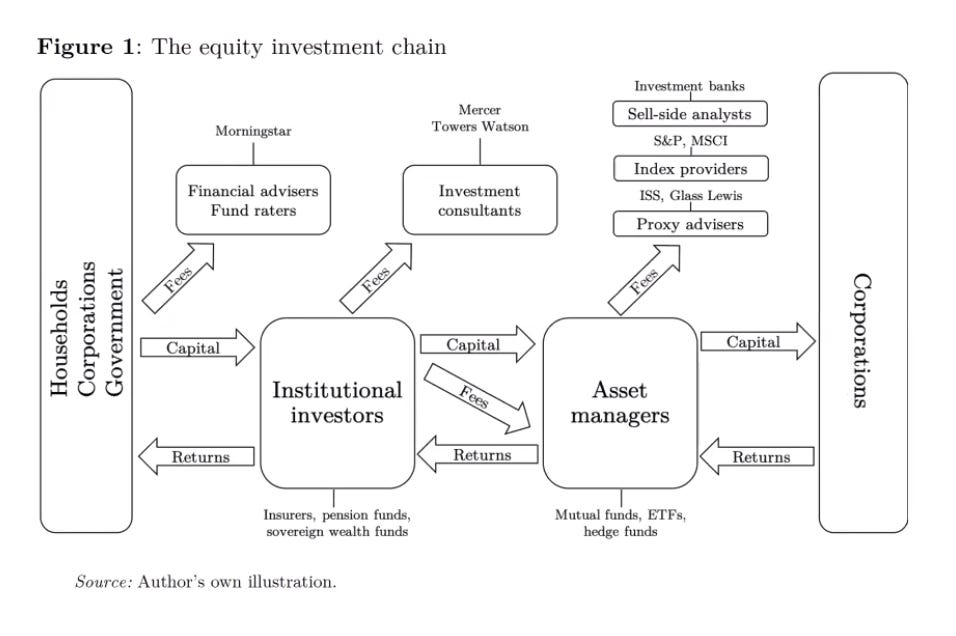

Source: Braun 2021

In this flow chart the key point to recognize is how asset managers earn their money. It isn’t through the returns of the corporations they invest in, but through the fees paid to them by institutional investors who aggregate the funds of households, corporations, governments etc. Those fees, of course, will ultimately only roll in if the asset managers earn good returns. But, if you stripped this down, the households could ultimately own the assets themselves. Adding the intermediation, advice, expertise, reduction of complexity etc etc is the key to the entire business.

Universal Owners

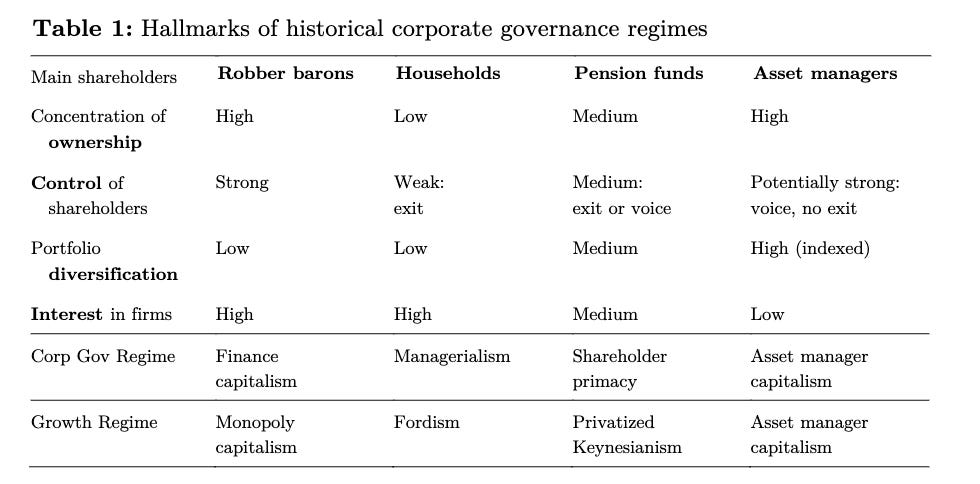

Asset managers are mediated owners. They are mediated also as a result of the sheer size of their portfolios. They are radically diversified, owning slices of practically every corporation worth anything. But their bulk means that their ability to exit stock is limited. They are simply too big. In this 2021 paper Braun develops a typology of historical models of ownership and control.

Like a robber baron, BlackRock has achieved a high concentration of ownership. Unlike a robber baron it has a huge diversification of what it owns and a limited interest in any particular bit of its portfolio. This somewhat paradoxical state of being into everything and unable to get out, gives rise to the idea that asset managers are what is called “universal owners”.

On the history of the concept of “universal owners” this paper by Mercer Investment Consulting from back in 2006 is interesting:

“Universal ownership” is a term coined by Bob Monks and Nell Minow in Corporate Governance in 1995 to describe an institutional investor owning such a wide range of asset classes distributed among economic sectors that the organization effectively owns a slice of the broad economy. The authors recognized that the “Pension Fund Revolution” described by Peter Drucker in 1975 was well under way. In the United States, by 2005 the 100 largest institutions and managers owned 52 percent of all publicly held equity. Not only do institutional investors own a majority of the public equity of the world, but through that ownership, their success as investors is dependent on the performance of the economy at large. Large owners who own a representative “slice” of the economy are more dependent on general macroeconomic performance than on the performance of any one stock or portfolio.

ESG

As universal owners, the new “moral money”, Environmental Social and Corporate Governance agenda is a perfect fit for asset managers. But what does it amount to? The suspicion must be that

a. it is a PR boondoggle/greenwashing

or b. if it is not a boondoggle (since an actual climate crisis might really be bad for global capital), then the involvement of the universal owners will come at a price.

On the actual voting behavior of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street as universal owners, this new working paper is essential reading.

Derisking

On the question of what price Larry Fink demands, THE INDISPENSABLE person to follow is, of course, Daniela Gabor. I’ll do another post at some point introducing Daniela’s agenda. But if you haven’t already, add Gabor along with Blyth and Braun to your regular reading.

What BlackRock wants is exorbitant. It wants the public balance sheet to step in backstop any risks that asset managers might be running in making serious ESG investments. And because BlackRock is a huge universal owner, when it asks for a public backstop it means the public balance sheet of the world - no kidding! Larry Fink of BlackRock has made clear, repeatedly, that he wants all the capable governments of the world to pitch in to increase the loss absorption capacity of the IMF and World Bank balance sheets.

It is almost as though someone at BlackRock has been reading the Communist Manifesto and is asking themselves: Where is that “committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie” that we were promised? And no, a 1990s-style ad hoc combo of Greenspan-Summers-Rubin won’t do the trick. Universal owner → universal public backstop please!

A preliminary climax of this agenda was reached in November 2021 at COP26 with Mark Carney’s announcement that he had rallied $130 trillion in institutional funds behind driving the drive to energy transition.

Prof Gabor has developed an entire interpretation of the political economy of our current moment in terms of the political economy of “derisking”. Here is an excellent talk she gave around COP26.

In this key slide Daniela summarizes the fundamental different in political economy produced when government conceives its role as being essentially to derisk investment by gigantic private asset managers.

For Daniela’s roundup on COP26 check out this short essay on the great Phenomenal World blog.

So … how did we get here?

Investigative journalists all over the world have been after the BlackRock story.

Back in 2018, the award-winning reporting team at Investigate Europe did this excellent report.

Deal of the Century

The bit that interests me most is the way that BlackRock’s rise was fueled by the shock of 2008.

What is fascinating about this moment are two things. At an abstract level it shows how crises can accelerate structural long-term change. Event and structure are not distinct, but interwoven. More concretely, focusing on 2008 encapsulates the shift from a bank-centered financial model to the rise of asset management. In 2008-9, banks were discredited by the crisis and literally began to cannibalize themselves to survive. Guess who swooped?

As this excellent Bloomberg report spells out, the moment when BlackRock leapt ahead of its peers came in the spring of 2009 when its snapped up the iShares ETF unit, part of the fast-growing, San Francisco-based fund management subsidiary of Barclays Global Investors Ltd. (BGI).

Crucially, the Barclays deal shifted BlackRock from an asset manager known for its active asset management, to being a firm with a strong position in passive finance. It was by buying Barclays’s ishare business that BlackRock got in on the booming market for ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds).

As this excellent FT report makes clear, BlackRock’s historic acquisition of the Barclays ishare franchise was anything but foreordained. It almost did not happen.

While Mr Fink was in talks with Barclays, the bank agreed a $4.4bn sale of the iShares unit to CVC Capital Partners, Europe’s leading buyout group. “We heard rumours about the CVC deal two months before it was announced [in April], and I was talking to Bob Diamond and John Varley throughout that two-month period … Barclays had a ‘go shop’, and they used CVC as a stalking horse, basically, to get other people interested. We were the only firm that was given an exclusive right to buy all of BGI, not just iShares,” said Mr Fink. … A person close to the situation said Mr Fink spent 48 hours calling in favours as he frantically searched for fresh sources of capital from sovereign wealth funds and hedge funds to finance the deal. Mr Fink had to find new backers because he could not get “full transparency” into where bankers were sourcing capital from, some of which was to come from Middle East investors.

At the time, it was far from obvious to the financial markets, that the BlackRock acquisition of ishares was even a good deal. “A private poll of institutional investors by Create-Research at the time found that just 28 per cent thought the deal would be a game-changer, with 35 per cent believing the merged company would be an unwieldy giant.” Nor did BlackRock’s advantage over Barclays appear immediately in its share price. It was only in 2013 with the ongoing problems in banking, that the historic divide became increasingly obvious.

Why was Fink willing to take the risk that he did at such a precarious moment? As he himself put it to the FT.

As a large fixed income manager, BlackRock was in regular talks with many governments as the financial crisis unfolded. “We had a strong belief in early 2009 that governments worldwide were going to do whatever they needed to do to stabilise the world,” Fink said.

The crisis not only transformed BlackRock’s business. It also changed its political position. The two fed off each other in a synergistic cycle. As Daniela Gabor might put it, Fink’s entrepreneurial genius consisted in gambling on the fact that the world would be derisked for him and his firm. If Goldman Sachs was the preferred partner of US financial governance in the 1990s and 2000s, since 2008 BlackRock has emerged as a key player. In the Biden administration BlackRock veterans play a stand out role. But the moment when BlackRock moved into this new role came in the spring of 2008. It was in brokering the deal that handed Bear Stearns to JPMorgan, along with a juicy Fed subsidy that Larry Fink emerged as the “Mr Fix It” of Wall Street.

As this Fortune report described it, BlackRock was everywhere:

"I think of it like Ghostbusters: When you have a problem, who you gonna call? BlackRock!" says Terrence Keely, a managing director at UBS, who worked with BlackRock last spring to dispose of a troubled $20 billion portfolio of mortgage-backed securities (BlackRock unloaded it for $15 billion).

In 2020 the Fed would again turn to BlackRock to help with its response to the Covid crisis.

Are there conflicts of interest involved in acting on the side of the buyers, the sellers and the government in between? Sure there are. You can’t avoid those as a universal owner. But Larry Fink’s answer is remarkably frank. This from the WSJ from back in 2009 presumably still holds:

Aside from its government-mandated role, BlackRock is paid by clients to value $7 trillion of fixed-income securities -- more than the entire Treasury bond market. Through a separate unit BlackRock manages $1.1 trillion of money for customers including California's pension plans.

"We have a two-decade record of managing conflicts, which is why we have been hired by many global institutions and governments," says Mr. Fink, a former Wall Street trader. "Our clients trust us."

The technology - Index Funds

When it came to buying and integrating Barclays Global Investors BlackRock clearly had many advantages. It was an insider on both Washington and Wall Street. It could mobilize the funds when it needed to. But it also already had a preexisting link to BGI, through technology. As the FT report by Attracta Mooney and Peter Smith spells out.

BGI’s bond division was already a client of Aladdin, BlackRock’s risk management technology platform that is now commonly used in the asset management industry. “We could quickly analyse the whole fixed income component of BGI [as part of due diligence ],” said Mr Fink. “Aladdin gave us confidence that we were going to be able to, more than any other firm, do a big acquisition and integrate on to a common platform.” “We’re going to have one technology platform as integration is completed. We are going to have one organisation. We’re not going to have silos; we’re going to have one organisation,” Mr Fink recalled.

Aladdin is a powerhouse for BlackRock. But technology plays a key role in the rise of asset manager capitalism more generally. And the key technology here are index funds.

For a wonderfully well-written and deeply researched account of index funds and their history, check out this fascinating book by Robin Wigglesworth of the FT.

Robin gave this interesting interview on some of the characters in his rich story.

Why does all this matter?

Check out the video by Daniela Gabor for the most comprehensive answer. But in brief, asset manager capitalism is a structure of power. It is interwoven with policy. It has expanded at the same time as central bank asset purchases (QE) have become the key tool of macro-policy. It is, as Daniela has show, expanding the frontiers of financialization into every area of life. Asset managers need yield. They get yield by financializing everything from real estate to natural capital. And this is capitalism. As Mark’s video at the top spells out, it is interwoven with social structure, inequality and class.

*******

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. But it is voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters that sustain the effort. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options:

Thanks for reading! And share with your friends.

I realize this will be an oversimplification, but if Blackrock (i) owns everything, (ii) cannot exit and (iii) expects the governments of the world to de-risk . . . the world, this sounds more like some kind of mirror-world communism than capitalism, with the dictatorship of the proletariat replaced by the dictatorship of Larry Fink. Coming at it from another angle, if someone owns approximately everything, and will go on owning it approximately forever, why should anyone be paying them anything more than a nominal record-keeping fee? As I said, oversimplified, but what a world we live in.

I've been trying to figure out how the asset managers became market consolidators. It's legitimately bothered me. Thanks Adam. I subscribed immediately after following the cast of characters you introduced me to in your analysis.