Afghanistan is in the grip of an escalating humanitarian disaster of epic proportions.

More than half of the population is facing “extreme levels” of hunger. As António Guterres, United Nations secretary-general, has put it: “For Afghans, daily life has become a frozen hell.”

The World Food Program distributed food to eight million people in December. According to the WFP 23 million people have sunk to crisis or emergency levels of food shortage.

A million children are at risk of starving to death. Food prices are soaring. Since the summer, the price of wheat flour jumped 53%, cooking oil is up by 39% and sugar by 36%, according to the U.N.’s World Food Program.

Heavy snow is blanketing the country making fuel for cooking and warmth a vital necessity.

The Taliban regime has no answers. The regime’s Prime Minister, Mullah Hassan Akhund recently declared in a speech that the Taliban movement had promised to expel foreign forces, establish an Islamic Emirate and bring security. It had not promised to feed the population. Famine was, literally, an act of god.

“Remember, the Emirate had not promised you the provision of food. The Emirate has kept its promises. It is God who has promised his creatures the provision of food,” Mr. Akhund said.

Fatalism aside, this is a disaster that was widely predicted. As I discussed in Chartbook #35, Afghanistan’s economy was critically dependent on foreign aid. Comprehensive sanctions were a death sentence.

Despite its poverty, Afghanistan has sufficient foreign exchange reserves - $9.4 billion - to easily cover necessary imports. But following the Taliban takeover, the reserves were impounded by the US Treasury.

Multilateral banks have pulled back too. At the end of last year, the World Bank released $280 million from the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF) to prop up NGO-run health care services and allow the UN to deliver food is critical but insufficient. But this is a pittance. Afghanistan needs billions.

The World Bank board is not even due to consider the situation until mid-February, at the earliest.

Time is critical. Afghanistan’s situation now is nowhere near as bad as it is going to get. Famines typically reach their most intense stage in the spring and early summer, in the agonizing wait for the next harvest.

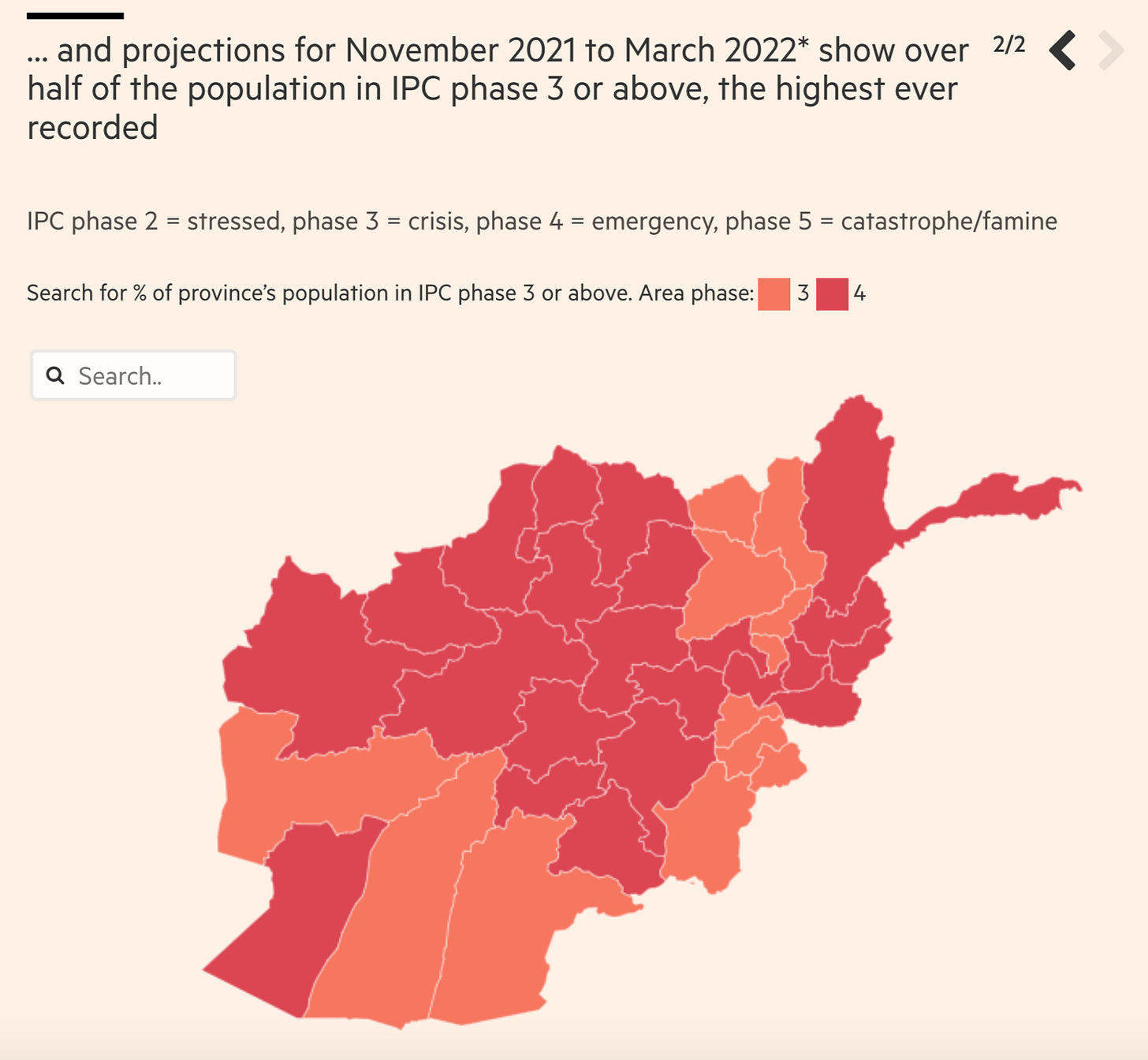

By March the UN predicts that over half of the population of Afghanistan will in IPC phase 3 or above of food crisis/famine, the highest ever recorded.

Source: FT

Not only is Afghanistan hobbled by sanctions, but its currency is depreciating severely, raising the cost of imported food.

Source: FT

Rumor has it that the depreciation is driven in part by the dollar purchases of big Pakistani’s businessmen who smuggle US currency into Pakistan, whose economy is also under serious financial pressure.

The depreciation of the Afghan currency would be even worse, but for the fact that the Afghan central banks depends on foreign companies to print its bills and thus cannot actually inflate the currency as it might wish.

The paralysis at the central bank is indicative of the wider disintegration of the Afghan state. Hundreds of thousands of civil servants, including virtually all teachers, have not been paid in months. This leaves their families desperate and, at the same time, erodes the capacity to uphold public order, except by brute force.

The United States can stand back from this apocalyptic scene. President Biden has made good on his promise to get the troops out. It is Afghanistan’s neighbors that are in harms way.

Pakistan has as much responsibility as anyone for bringing to the Taliban to power. Now it is experiencing the blowback in mounting tension in the border regions.

From October through the end of January, more than a million Afghans in southwestern Afghanistan have begun to migrate towards the border with Iran. Aid organizations estimate that around 4,000 to 5,000 people are crossing into Iran each day.

For many Afghan refugees, neither Pakistan or Iran is the final destination. Desperate to contain the refugee flow, the European Union has pledged over $1 billion in humanitarian aid for Afghanistan. “We need new agreements and commitments in place to be able to assist and help an extremely vulnerable civil population,” Jonas Gahr Store, the Norwegian prime minister, said in a statement at the U.N. Security Council’s meeting on Afghanistan last month. “We must do what we can to avoid another migration crisis and another source of instability in the region and beyond.” Gahr Store has opened framework discussions with the Taliban in the hope of managing the crisis.

What should be done?

David Miliband, president and CEO of the International Rescue Committee, has proposed a sensible, 5-step plan.

Release all private funds of Afghan citizens and corporations frozen in overseas banks in Europe and the US

As the largest shareholder, the US should support the World Bank to urgently release the remaining more than $1.2 billion sitting in the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund. As Miliband says, this should now be directed to a wider set of programs to resume essential services, including paying civil servants such as teachers, nurses and other essential workers.

The US and other donor governments should support a joint World Bank/IMF mission to Afghanistan and pathways for technical assistance for the Afghan central bank. As Miliband puts it: “Afghans need a functioning economy, and it begins with a functioning central bank.” This would enable channels of communication between the international financial community and Taliban authorities to be reopened.

Clarify the sanctions regime to be imposed by the US and other Western powers, so that private business can engage with some degree of confidence.

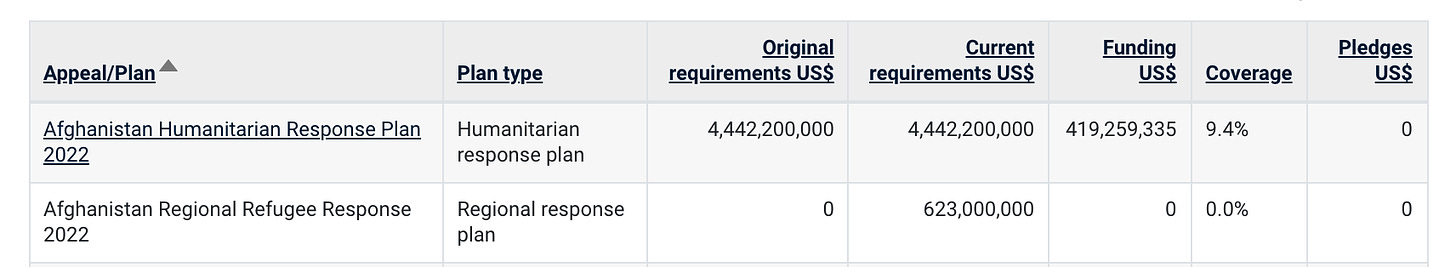

Finally, donor states must urgently meet the short-term UN humanitarian aid appeal of $5 billion -- the largest single country appeal of its kind ever. America’s announcement of over $300 million in aid is in Miliband’s words “both meaningful for aid operations and a symbolic effort that should be leveraged to galvanize other donors.” If the crisis is allowed simply to escalate, the UN warns that it could soon be asking not for $ 5 billion, but for $10 billion.

Miliband’s action points are modest, but they far exceed the current effort.

As of early February 2022, according to UN data, less than 10 percent of the $5 billion appeal is funded.

The US Department of Treasury has recently clarified that international banks can transfer money to Afghanistan for humanitarian purposes, and aid groups are allowed to pay teachers and healthcare workers at state-run institutions without fear of breaching sanctions on the Taliban.

This may provide some relief.

But Miliband steered well clear of raising the truly sensitive issue: the fate of Afghanistan’s $9.4 billion foreign exchange reserves, currently frozen by the US.

Last week, Congressional Progressive Caucus Chair Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., secured a vote in the House on this crucial question. As the Intercept reported, she did so by tying her amendment to the anti-China omnibus bill which

will subsidize the U.S. semiconductor and other industries with hundreds of billions of dollars and ratchet up military activities in the Indo-Pacific region. The House of Representatives passed the legislation — called the America Creating Opportunities for Manufacturing, Pre-Eminence in Technology and Economic Strength, or COMPETES, Act — on Friday. But the House rejected Jayapal’s amendment with 175 yes and 255 no votes, as 44 Democrats joined Republicans against the measure. (Two Democrats and one Republican did not vote on the amendment.)

Jayapal’s provision, drafted with Rep. Jesús García, D-Ill., would require the secretary of the Treasury to provide Congress with an assessment of the humanitarian suffering caused by U.S. sanctions on Afghanistan and its confiscation of the country’s foreign-held money. It would also mandate a review of illicit financial activities with China amid a breakdown of Afghanistan’s banking system.

At least eight other amendments to the broader bill target Afghanistan, reflecting a range of approaches to sanctions and relief. One provision sanctions individuals for trading the country’s rare earth minerals; another provides visas for Afghan Fulbright scholars. But none call out the Biden administration for its asset seizure.

Meanwhile, the World Food Program waits for the food deliveries that could save millions from misery.

WFP’s has a well-oiled a fleet of 171 trucks that manage to transport food across all of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces. However, “the most important element is missing,” says Assemy – funds to make sure WFP can scale up as it must in 2022.

In these weeks and months, Afghanistan’s fate hangs in the balance. As Abdallah al-Dardari, the UNDP’s Afghanistan head, told the FT: “It can either implode with massive regional consequences, or something has to happen, but you cannot continue monitoring the collapse of each of these systems, with horrendous humanitarian consequences,” says al-Dardari. “People cannot just wait and see their children starving to death.”

Increasingly I feel as if American Foreign policy is like how Fitzgerald described Tom and Daisy Buchanan in Gatsby: "They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

In reply to a Forever Wars (Spencer Ackerman) post about sanctions as weapons of mass destruction, I wrote the following, which seems apt here as well: "So, if it's a war crime to target civilians with munitions, why is it not a war crime to target civilians with sanctions? I mean, imagine that we were 'at war' with Russia and that the death and destruction caused by the deep freeze in Texas last year was the result not of poor energy infrastructure and regulation but of Russia targeting Texan energy infrastructure. Would Russia be guilty of a war crime? So what's the difference if US sanctions - whether unilateral or multilateral - starve or otherwise destroy the lives of Iranian or Afghan civilians? If a policy is killing civilians, does it really matter if the policy is military or economic?"

Although we are no longer conducting a 'kinetic' war in Afghanistan, I think our withholding that > $9 billion of Afghan assets constitutes, if not a war crime, then surely a crime against humanity.