Chartbook #76: Strategy of Tension - updated on the economic fallout from Russian-Ukraine crisis

First off, a reminder. Ukraine is huge.

Over the last week, the most remarkable diplomatic development has been the emergence of a stark difference in stance between Ukrainian government and Washington.

On the one hand coming from both US and UK sources there is the escalation of warnings about impending war. That is increasingly unwelcome in Kyiv and has had the effect of raising tensions between Ukraine’s government and the Biden administration.

The problem is not that the Ukrainian language lacks a word for “imminent”, as was rumored on the politico website!

The deeper reasons for the difference are outlined stridently but effectively in this thread by E Hunter Christie.

The US and UK, for their own reasons, are staging this crisis as a classic war scare. By contrast, Ukraine’s President Zelensky has to foreground the reality of an agonizingly extended and ruinously costly confrontation with no clear beginning, middle or end. The former permits a relatively clean ending that caps the commitment of the Western powers, the latter would require the West to provide Kyiv with long-term and sustained support.

This piece in the Guardian by Dan Sabbagh and Luke Harding makes the case very clearly.

As Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, said on Friday, high tensions with Russia are not new “We have been in the situation for eight years,” he said. The analysis in Ukraine diverges from the west’s assessment of the crisis as primarily a military one. The belief in Kyiv is that Vladimir Putin’s goal is the long-term destabilisation of Ukraine, and that the Russian leader may have other objectives than invasion.

Alexander Clarkson, who is an essential follow, put the point with characteristic clarity.

The piece by Barbashin that Clarkson is reacting too is excellent on the divergent perspectives on the conflict within Russia’s think tank elite.

As Barbashin puts it:

The more moderate wing Russian international affairs specialists — among which Andrei Kortunov and Dmitry Trenin stand out — are increasingly suggesting that the Russian leadership should promptly organize a glorious way out of the current situation, declaring victory with whatever they have in hand right now. … Another approach, however, is arguing for doubling down. Supporters of a more conservative views — most notably the voices of Sergei Karaganov, Dmitry Suslov and Fyodor Lukyanov — are de facto accusing their more moderate colleagues of insufficient ambition, urging to them look at the current confrontation as an opportunity for a final divorce from the Western-centric world. … It is obvious that neither one group, nor the other, knows what Putin really wants to get from the West and Ukraine, how many action plans he has, and which logic he leans more towards on Tuesday and which on Wednesday.

The longer-term (and more realistic) view of the conflict brings the question of the economy and the relative survivability of Ukraine and Russia into focus. On the Ukrainian side the damage is already being felt.

As Nelles remarks:

This is why, other than preventing the further invasion in the first place, economic assistance to Ukraine is now more important than ever. The EU stepped up announcing up to €6.5 bil. in 'investments to support economy, recovery, growth.'

The EU’s promise came in a statement made by von der Leyen and were confirmed in meetings between EU Commissioner for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Olivér Várhelyi and the Ukrainian government.

“In Kyiv today [January 26]: with President [Volodymyr] Zelensky I confirmed EU's continued commitment to Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity + socio-economic resilience. We will mobilise up to €6.5 billion in investments to support economy, recovery, growth, starting with five flagship projects,” Várhelyi wrote on Twitter.

The key word here may be “mobilise” or “leverage”. This usage often allows the EU to leave open precisely how much public EU money is actually involved. A lot of financial magic can be performed by leverage.

All the way back to 2013 this has been the question. Is the EU willing to put serious money behind its talk of supporting Ukraine’s sovereignty? What will be the balance for Ukraine’s population, vested interests and politicians between discipline/reform and economic and financial benefits? Those benefits can, of course, take many forms: investment, credit, trade, opportunities for migration, technology transfer etc.

If you make this kind of point, defenders of the EU are wont to point out, that since 2014 Ukraine has received 17 billion Euros in grants and loans which is a lot of money for a non-member. That is entirely fair. But the problem is that in this case what is “enough” is determined by unusual factors i.e. Ukraine’s deep economic malaise and the pressure that Russia can apply.

In the mean time, Ukraine’s debt is taking a battering. As Bloomberg reports.

Ukraine’s foreign bonds have lost 7.5% this year in dollar terms, the worst performance in emerging markets after Argentina, according to a Bloomberg index. Notes due in 2033 last traded at or above par in mid-November and the bonds fell in early trading Monday. The hryvnia also fell, weakening to the lowest levels against the dollar in more than a year.

Source: Bloomberg

As this excellent piece by Ben Hall and Roman Olearchyk in the FT makes clear:

Solid economic growth of 3.2 per cent last year, buoyed by high prices for Ukraine’s commodity exports, was a bright spot for Zelensky, who appears an increasingly isolated and unpopular figure. Since his election in 2019, he has made modest progress in tackling graft, is struggling to reform a corrupt judiciary and is locked in a power struggle with some of the country’s powerful oligarchs. However, the economy has now taken a sharp turn for the worse. Inflation has shot above 10 per cent. The hryvnia has lost 6 per cent of its value against the US dollar in a month. Companies are struggling with surging energy costs. Ukraine filled up its gas storage facilities last year before prices spiralled, but it will need billions of dollars to meet next winter’s needs. Investors have taken fright. Ukraine is, in effect, locked out of capital markets, although the biggest bond redemptions of the year are not due until September. “Even if nothing happens, it is a macroeconomic shock,” says Tymofiy Mylovanov, a former economy minister and adviser to the presidential administration. “It will have an impact on mood, morale and allocation of resources.”

Russia is in a far stronger position, but it is by no means immune.

Sergei Guriev who teaches economics at Science Po is an excellent person to follow on all things to do with Russia’s economy. As he remarks in the FT:

January 24 was also unprecedented for Russia’s Central Bank move to support the rouble. Russia’s budget breaks even when the oil price is at $44 per barrel. When it is higher, the Russian Finance Ministry uses excess export revenues to fill up the sovereign wealth fund by taxing the oil firms and handing these revenues to the Central Bank to buy dollars. Since today’s oil price is almost double the break-even level, the Central Bank should be investing heavily in dollars. On January 24, it stopped buying any.

Russia’s financial markets will continue to feel the burn for some time. How far this might affect global financial markets will be a matter for stress testing.

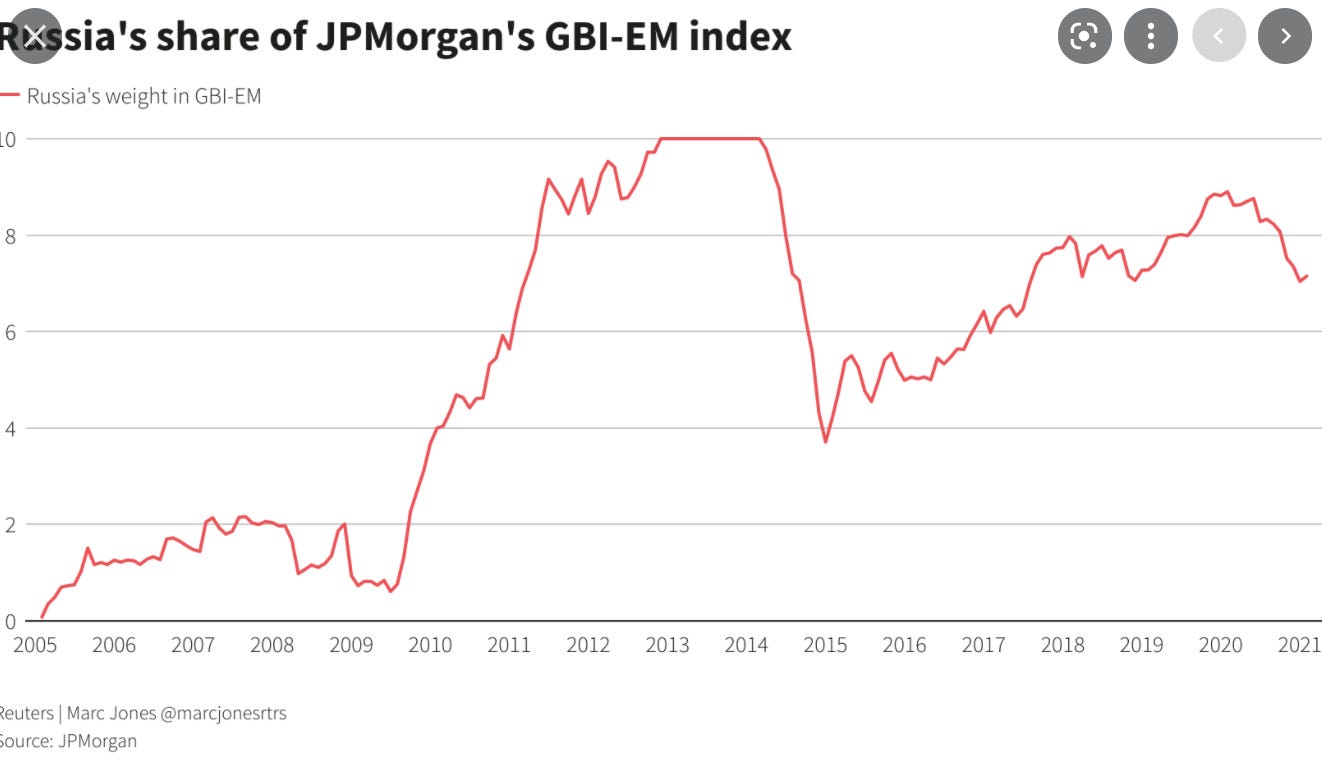

"Russian debt comprises more than 7 per cent of a widely followed JPMorgan index of emerging market local currency bonds, meaning many big investors are in effect forced to hold the bonds or risk underperforming their benchmark."

A graph from Reuters shows how the share has fluctuated over time.

Major Western financial players like Unicredit are reevaluating their interests in Russia.

Meanwhile, analysts have been hard at work crunching the sanctions scenarios.

Gas remains the critical issue. As Bloomberg reports, Russia’s gas production is at all time, record highs. But exports are another matter. Flows to Europe will be watched anxiously. The deployment of a Russian LNG supply vessel to the Baltic waters around the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad it is not a reassuring sign.

That said, Europe’s situation is easing.

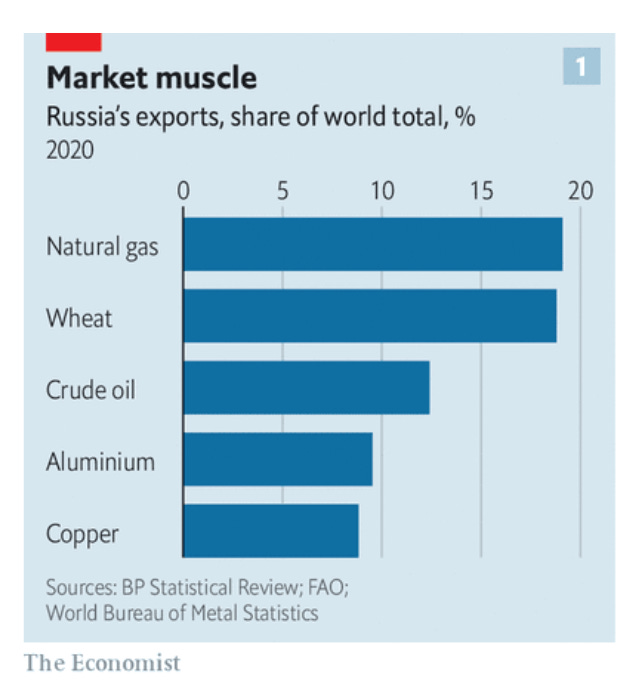

Beyond gas, the footprint of the Russian economy in global commodity markets is huge.

Source: Economist

Russia’s reemergence as a major exporter of grain is a dramatic development of recent years. It is all the more significant, because in the market for grain, alongside Russia, Ukraine is also a major exporter. And the breadbasket of Ukraine are precisely the eastern regions most vulnerable in case of Russian military action.

A war between the two would impact global markets from two sides. And this is all the more concerning, because of who buys Russian and Ukrainian grain.

As this fascinating article in Foreign Policy by Alex Smith of the Breakthrough Institute reports

about half of all wheat consumed in Lebanon in 2020 came from Ukraine, according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Relying on bread and other grain products for 35 percent of the population’s caloric intake, Lebanon is critically dependent on Ukrainian wheat. Of the 14 countries that rely on Ukrainian imports for more than 10 percent of their wheat consumption, a significant number already face food insecurity from ongoing political instability or outright violence. For example, Yemen and Libya import 22 percent and 43 percent, respectively, of their total wheat consumption from Ukraine. Egypt, the largest consumer of Ukrainian wheat, imported more than 3 million metric tons in 2020—about 14 percent of its total wheat. Ukraine also supplied 28 percent of Malaysian, 28 percent of Indonesian, and 21 percent of Bangladeshi wheat consumption in 2020, according to FAO data.

In wider collateral damage one also needs to consider Russia’s importance as a major destination for Central Asian migrant labour. As data from the World Bank makes clear, the most prominent sources of labour are Uzbekistan and Tajikistan

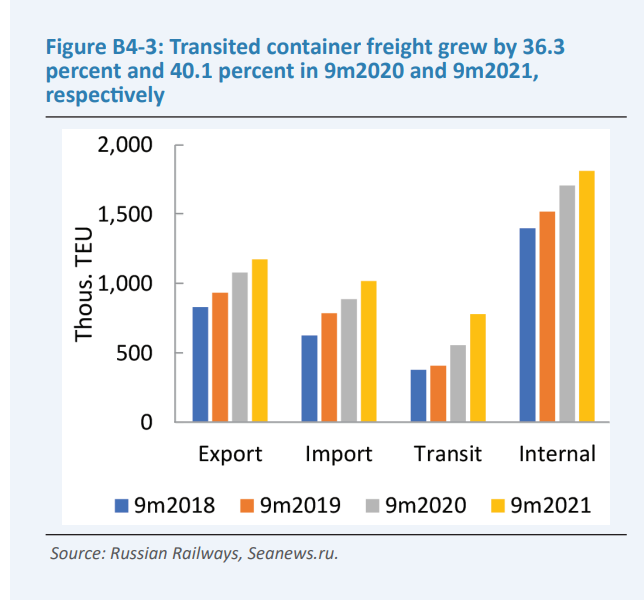

And remember all those stories a few years back about the rail routes from China to Germany? Well, given surging container shipping costs post-COVID, those once uneconomic overland routes have actually come into their own. As the World Bank reports: Rising container shipping costs have contributed to a growth in container traffic transiting Russia via rail, rising 40 percent, yoy, in September 2021 to 782,000 TEU. In this respect too there might be some nasty surprises from an all-out economic war.

******

I love putting out Chartbook. I am particularly pleased that it goes out for free to thousands of subscribers around the world. What supports the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying subscribers. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporting subscribers, pick one of the options here.

One of the traditional problems faced by autocrats is that they often have no exit strategy that guarantees their lives and/or fortunes. So they tend to stay on until the very end and to the impoverishment of their people. If that principle applies to Putin, then shouldn’t the EU offer Russia a “Peter the Great Program” by which I mean a series of incentives leading to the greater assimilation of Russian into the European economy and, ultimately, way of thinking? Such a program could appeal to the Russian People’s sense of History (by finishing the job begun by one of their most famous historical figures) and their desire to be taking and treated seriously by Europe, while providing Putin with something of an off-ramp toward retirement.

It seems to me that Russia has an historic choice to make as to its long term survival between increasingly closer ties to Europe and risking becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of China. An outreach along the lines of a “Peter the Great Program” might be a productive alternative to constant instability and saber-rattling (if not outright conflict). I suspect the average Russian might, at a minimum, favor limiting corruption and cronyism while putting the Russian economy on a surer footing.

I would hope someone is giving some thought to such a project. Perhaps Prof. Tooze might sketch out the broad outlines of what such a project might look like, unless he finds the approach a non-starter.

One thing struck me: the Christie thread could be turned around and remain equally correct.

"Hard for non-Westerners to understand and accept, but this means there is no brighter future to look forward to, there is no sunlit upland to get to after going through a rough patch with Washington, the opposition is permanent, and the conflict is permanent, already now.

Deep down we ought to know this - think of election interference, military threats, assassinations on our soil, deliberate deception and manipulation on the part of American officials, permanent espionage.

And yet we keep on expecting some magical moment, some clarity, maybe some catharsis even. But that is not the way of the American Regime. Expect no fixed point, always expect a sliding scale of ambitions and full-spectrum violence."