Chartbook #62: Once a giant: the decline of the Bundesbank - Or, who is Joachim Nagel and will it matter?

This morning Germany’s Finance Minister Christian Lindner confirmed that he and Chancellor Scholz would be jointly nominating Joachim Nagel to succeed Jens Weidmann as President of the Bundesbank. What does it mean for Germany and Europe’s monetary policy?

In 2019 Weidmann’s ambitions at the ECB were blocked by Lagarde’s appointment. He has had to give ground on policy issues like climate. Perhaps not surprisingly, Weidmann chose not to serve out a full second term as Bundesbank President.

Since his appointment to the Bundesbank following Axel Weber’s abrupt resignation from the frontline of central banking in early 2011, Weidmann made himself into the figurehead of financial conservatism in Europe. He refused to fall into line with the majority on the ECB board and allowed himself to be instrumentalized by Germany’s populist media.

Now, we all want to know, who is Joachim Nagel and how he might differ from Weidmann? But, an even more important question is whether it will matter and if so, how. Or, to put it less facetiously, can Weidmann’s successor organize a more graceful adjustment to the Bundesbank’s new and diminished role within the Eurosystem? If he can, it will remove a major source of tension in European politics and make a substantial contribution to the solidity of Europe’s common currency. Is Nagel the central banker to reconcile German politics to the de facto retreat of the Bundesbank from the top tier of global monetary politics to its role, today, as a subordinate player in the Eurosystem?

***

Once the Bundesbank was a mighty monetary power, a key player at the global level and an icon of West Germany’s miraculous recovery after 1945.

That surprising development is described from the German political angle by the fascinating political and cultural history of the Bundesbank that Simon Mee published with Cambridge University Press in 2019.

As Mee shows, postwar Germany was the site for the construction of a

‘monetary mythology’, a carefully constructed historical narrative about the inter-war period of Germany that flourished in the West German public sphere following the Second World War.24 It explores this myth-making by analysing how the lessons of Germany’s experience of inflation, namely the 1922–3 hyperinflation and 1936–45 inflation, became politicised in the post-war era and transformed into political weapons in support of central bank independence. In the debate surrounding the establishment of West Germany’s central bank, the country’s monetary history became a political football as central bankers, politicians, industrialists and trade unionists all vied for influence over the legal provisions grounding the future monetary authority. The debate centred on power

Bundesbank independence was an effect of domestic political battles. But also, crucially, of international factors.

Within the gold-backed, dollar-based Bretton Woods regime between 1945 and 1973, the remit for national central banks was severely constricted. It is only after the collapse of Bretton Woods that the Bundesbank could emerge as a dominant force in Europe and on the global stage.

As Benjamin Braun shows in a brilliant essay, the Bundesbank’s espousal of monetarism in 1973 helped to shape an entire narrative of money as an exogenous force that had to be tamed by central bank policy.

In 1970s and 1980s the Bundesbank demonstrated its independence by clashing repeatedly with the social-liberal governments headed by Helmut Schmidt. Here is how Inga Rademacher describes the situation in 1979 in a fascinating essay from earlier this year,

That the Bundesbank used the dependence of the Schmidt administration on lower interest rates during the process of bargaining shows how state actors strategically use political and economic conditions for bargaining outcomes (PTE 3). Since Schmidt tried to achieve a simultaneous harmonisation of interest rates across the G7 countries and a domestic fiscal stimulus in 1979 and 1980 (further elaborated on in PTE 4), the administration was particularly vulnerable to higher interest rates. In a cabinet meeting in 1980, Schmidt laid out his plan to harmonise interest rates internationally and urged the Bundesbank to use ‘all available measures to keep international economic relations intact’ (BArch 1980, 5th cabinet meeting). However, the Bundesbank rebutted that it was no longer in control of domestic interest rates as the upward pressures of international interest rates spilled over into the German economy. It was, therefore, of utmost importance that fiscal measures enhanced investor trust in the DM to limit capital flight (BArch, 1979, 126th cabinet meeting; BArch, 1980, 5th cabinet meeting).

To get a sense of how open the clash was at the time, read this report from Die Zeit in 1982 after Schmidt’s loss of the Chancellorship.

But the Bundesbank did not just have influence at the domestic level. It set the terms for interest policy within Europe and beyond. That involved it in a complex bargaining process with Germany’s European neighbors by way of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. The Bundesbank was suspicious of Bonn’s tendency to make concessions to Paris.

In the late 1980s three shifts ushered in the apotheosis of Bundesbank power. The liberalization of capital movements across Europe from 1988 increased vulnerability to capital flows. In 1988 the Bundesbank began a concerted push to raise interest rates and align them with those of the United States. And in 1990 the end of the Cold War and the process of German unification created further pressure to raise rates. The result was that the Bundesbank delivered a dramatic interest rate shock.

This moment is analyzed in this fascinating article from 2019 by Arie Krampf.

As Krampf summarizes his conclusions:

Bundesbank go-it-alone strategy in 1989 triggered a cross-national sequence of events that changed the international monetary order in a way that was consistent with the German interests. The transition was marked by a shift from the US-led pragmatist approach of international macroeconomic coordination to a rules-based approach founded on the principle of low-inflation–targeting. The article argues that this change took place despite the opposition of the Federal Reserve System (Fed) and the US Treasury.

This truly was the (anti)-heroic period of German monetary power. As the Bundesbank itself sees it, it helped to set in motion the worldwide diffusion of the independent central banking model.

But at the same moment, with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992s, steps were being initiated to curb its independent national power, through submergence in Europe’s common currency.

***

Where is the Bundesbank today?

It retains the nimbus of a major national institution. It stands for monetary solidity. But as no lesser authorities than Martin Hellwig and Isabel Schnabel reminded the Bundestag in 2019.

The fiction of the (national, AT) “we” elides the fact that the Bundesbank in its operative business is no longer a German institution, but a part of the supranational Eurosystem.

It is that awkward hybrid status that the President of the Bundesbank has to navigate.

Whilst the ECB could be presented as essentially continuing the Bundesbank’s heritage, it generated relatively little tension. But since 2008 that has no longer been the case.

The Bundesbank has been exposed as a somewhat lonely institution.

It is famously independent. But its President and Vice-President are simply appointed by the German government. Jens Weidmann’s main qualification for the job in 2011 was that he had been Angela Merkel’s economic and financial advisor.

There is no elaborate confirmation process as in the US. The other half of the board members by the Federal Council. They represent regional interests. And whereas other central banks have moved to a model of transparency and accountability, the Bundesbank lags behind.

Unlike the Fed, the Bundesbank doesn’t hold regular hearings with the Bundestag. One of the innovations prompted by the 2020 ruling by the German constitutional court on the legality of the ECB’s bond purchase programs was a hearing at which Weidmann laid out the monetary policy of the ECB for the Finance Committee of the Bundestag.

Of course the glory days of its first half century provide the Bundesbank with a nimbus. But it was rather peculiar circumstances that gave Weidmann his prominence.

First and foremost there was the eurozone crisis. This raised the stakes and gave Germany a veto of financial policy, though not over decisions at the ECB. Weidmann’s personal closeness to Merkel was important. As was the fact that circumstances and Merkel’s personal proclivities demanded a gradual adjustment of the conservative model of monetary and fiscal policy to realities in the Eurozone. This opened up a space for German conservatives to pose as the rearguard, defending the lost cause of the old Federal Republic. The AfD was the populist wing of this movement. Weidmann was its respectable face. This was a choice. As Schnabel has shown at the ECB, German central bankers can also choose to make themselves part of the process by which rules and institutions are adjusted to new realities.

In Weidmann’s defense, you could say that his rearguard action was important in giving voice to the pain of German conservatives, indignant at the situation they found themselves in and at the compromises that Merkel was making.

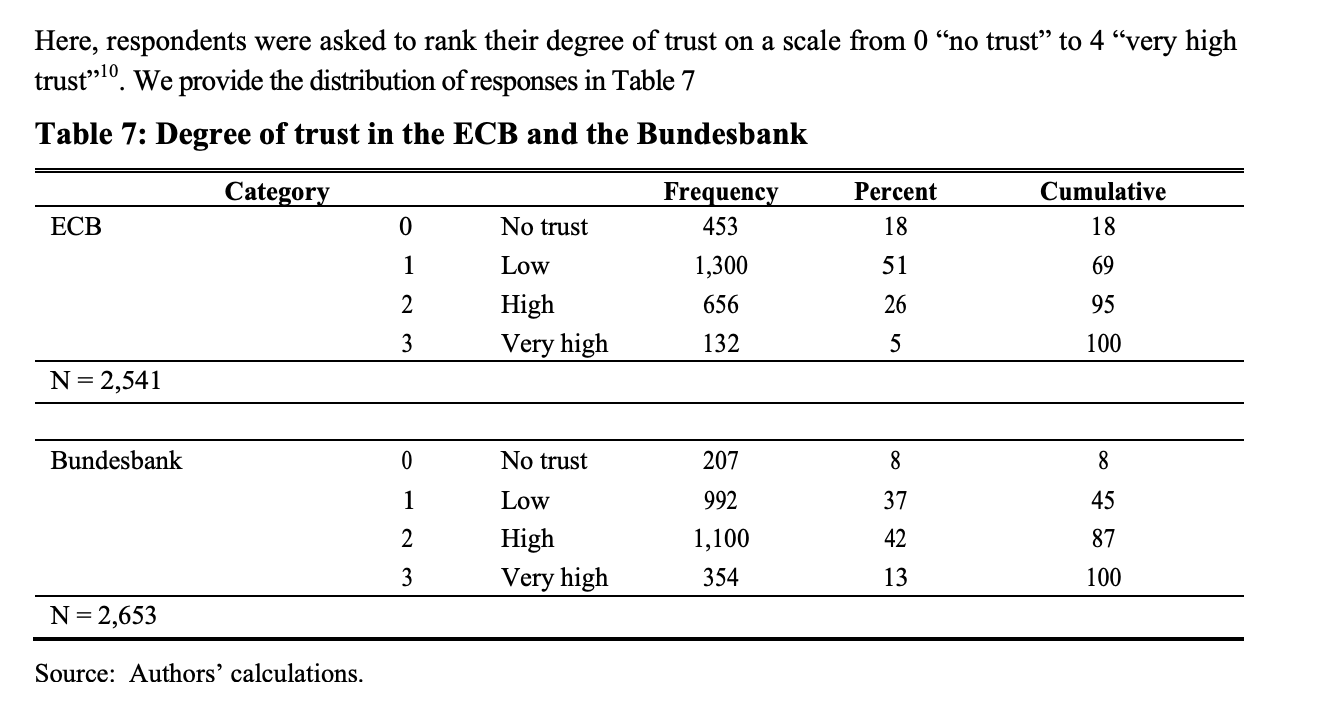

But the result was to encouraged the alienation between a certain segment of the German public and the ECB. As recent opinion polls have found there is a substantial gap between the share of the German public who trust the Bundesbank and the ECB, with a substantial minority expressing little or no trust in the ECB, whilst continuing to trust the Bundesbank.

Source: Mellina and Schmidt 2018

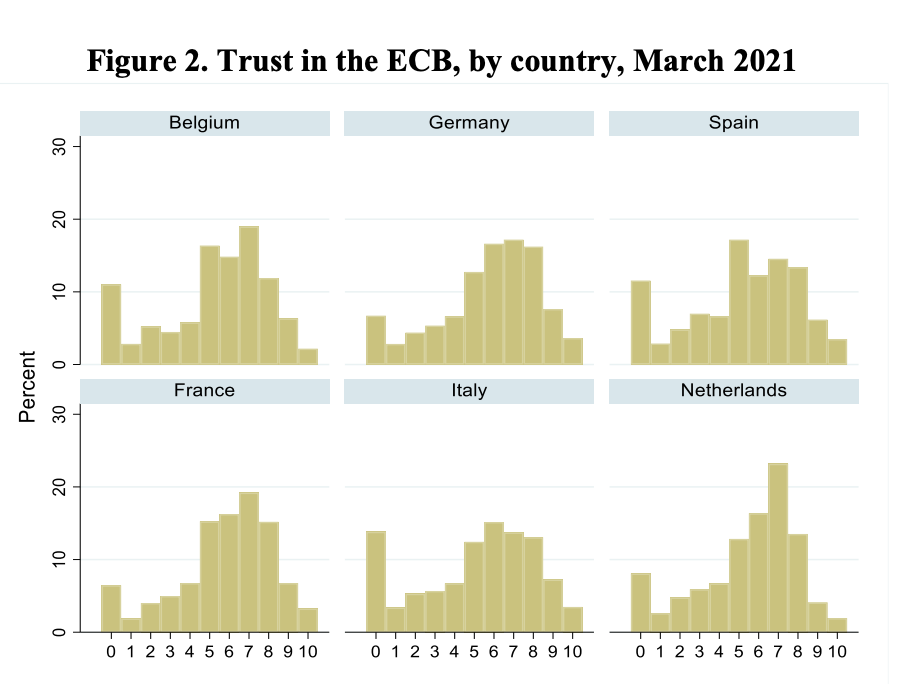

Though this is alarming, it should also be said that overall levels of mistrust towards the ECB are lower in Germany than in any other large economy in the Eurozone.

Source: Van der Cruijsen, Carin, and Anna Samarina. Trust in the ECB in turbulent times. DeNederlandsche Bank Working Paper 722, 2021.

There can be little doubt that what Olaf Scholz will be looking for in a Bundesbank boss, is not a conservative tribune of the Weidmann type, but someone who can continue to close the gap between German confidence in their national institutions and the authority of the ECB.

Schnabel was performing that role to a high degree at the ECB. Moving her to the Bundesbank would have been a demotion and would have posed the question of how to find an adequate replacement at the ECB. Joachim Nagel may be the man for the job.

***

The bios of Nagel rehearse the same lines, but in some sense miss the obvious. He’s a West German success story.

(He also seems to be a natty dresser. Nice outfit for riding a new Indian subway line!)

Nagel was born 1966 in Karlsruhe and, strikingly, he also chose to study there. The Karlsruhe TH is a renowned institution, but for Germany at the time this was an unusually conservative choice. There is little I can find on Nagel’s family background, but constrained family circumstances would be one explanation.

In the early 1990s, he won a coveted gig as an assistant and reseacher (Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter) at the University.

In March-October 1994 during Rudolf Scharping’s failed bid to unseat Helmut Kohl, Nagel took time out to join the SPD economics team. The party at the time was rocked by bitter arguments between left and right wings.

Nagel chose not to stay in politics. Instead, in 1997 at the ripe age of 31 he took his PhD from Karlsruhe with a PhD on the supply-sideconomic policy of Ronald Reagan.

Having skimmed the PhD two things stand out. It is not a highly technical exercise, more a narrative treatment of the 1980s economic policy scene in the US. He concludes that the Reagan administration was not successful in dramatically lowering marginal tax rates (state-level increase offset federal cuts). But, rather than rejecting supply side measures outright, in conclusion Nagel pleads for a reconciliation between demand-side macroeconomic policy and supply-side policy. Above all he calls for a coordination of policy.

After this rather undistinguished start, in 1998 he headed to Washington DC to do a year of research. Again this was enabled by local support, in this case the SEW-Eurodrive Stiftung, a Baden-Württemberg corporate foundation.

Nagel’s career began to accelerate when he returned to join the Bundesbank in 1998. Nagel spent his first few years at the Hanover Regional Office before transferring to the Bundesbank's Central Office in Frankfurt am Main in 2003.

At the Bundesbank Nagel was a protege of Hans-Helmut Kotz, also of the SPD.

In 2008 he was appointed Director General Markets. (Some timing, AT)

In December 2010, at the precocious age of 44, with the backing of Kotz, Nagel was promoted to the Bundesbank's Executive Board, where his responsibilities encompassed the Directorates General Markets and Information Technology. This is a big career leap. He replaced the right-wing SPD man Thilo Sarrazin, who will later become notorious for his views on immigration.

In this role Nagel represented the Bundesbank in international negotiations and until the end of April 2016 headed the bank’s crisis-management team.

In the BIS database of central bank speeches, Nagel has a limited presence. He Speaks most often about renminbi internationalization and seems to have been focused above all on markets.

In 2013 Nagel gave a joint interview with Benoit Coueré which suggests that he kept his cool during the taper tantrum. He does not come across as heady like Coueré, but he holds his own.

“Question: Some people argue that the ECB should not worry about risks and losses because central banks can operate with negative capital.

Nagel: There is a general understanding that central banks can function with negative capital. But the Bundesbank believes that this would be a dire signal.

Cœuré: This is exactly the right answer. Technically and legally it would be possible for the ECB to run with negative capital, but it would undermine the confidence in the ECB and the trust in the euro and therefore it should not happen.”

Nagel is widely seen as an “ordoliberal”, whatever that means. In German media that may just be code for “he is one of us”.

In 2015, as the FT reports, he gave an interview to the Börsenzeitung in which he expressed reservations about Draghi’s new QE program.

Shortly after the ECB started its quantitative easing policy of buying vast amounts of government bonds in 2015, Nagel warned in an interview with German newspaper, Börsen-Zeitung, of the “key danger” of an “intermingling of monetary policy and fiscal policy”. Echoing concerns often expressed by Weidmann during his decade at the helm of the Bundesbank, Nagel said: “There is a risk that the budgetary consolidation required in some euro countries will be put on the backburner”, which he said “could then increase political pressure on the ECB council to postpone an interest rate hike that is necessary from a monetary policy point of view”.

At his farewell from the Bundesbank in 2016, Weidmann stressed Nagel's

“decisiveness, ability to communicate, detailed knowledge of the financial markets and analytical skills. He also reminded the audience of Nagel's key role in bringing a renminbi clearing hub to Frankfurt am Main.”

Why did Nagel leave the Bundesbank in 2016?

According to German sources it was down to politics. In 2014 the SPD wanted Nagel to get the deputy position at the Bundesbank, but they were in a weak position. The CDU preferred Claudia Buch. Realizing that the wind was not blowing in his favor Nagel jumped.

Clearly, the idea of the Bundesbank as an independent institution does not mean that party cards do not play a major role in top careers!

After leaving the Bundesbank in 2016, Nagel joined the executive board of KfW, the German state-owned development and investment bank.

At the KfW 2017-2020, he was responsible for promoting developing and emerging countries. At the same time he was chairman of the supervisory board of KfW Ipex-Bank.

“Here comes the less pleasant episode.” According to one muckraking website:

“As part of a banking consortium, KfW Ipex-Bank granted the payment service provider Wirecard a loan of more than 100 million euros in September 2018 and extended it in mid-2019. At this point in time, however, the problems at Wirecard were no longer a secret. The lending falls during Nagel’s tenure as chairman of the bank’s board of directors. Wirecard went bankrupt in 2020. At Ipex-Bank, searches of the police and the public prosecutor’s office took place in the same year because of the initial suspicion of infidelity. Ipex-Bank ended up having to write off 90 percent of the money. Now it will become clear to what extent his mandate at KfW could be dangerous for Nagel if he soon took on a top position at the Bundesbank.”

Not recognizing the risk posed by Wirecard is a failure that Scholz and his team have in common.

At the KFW, Nagel found himself in a leadership position in one of key, public promotional banks, which is widely cited as a model for climate finance. To judge by his KfW web-presentation, Nagel may be greener than Weidmann.

“Many young people in particular are demanding greater climate action today; they do not think the measures taken against global warming to date have been adequate. What would you say to them? Where do we stand four years after the passage of the Paris Agreement?

Dr Joachim Nagel: The international climate agreement is still intact, despite scepticism in some capital cities, particularly in Washington. What’s more: we are seeing a growing commitment to climate change mitigation in all areas of the world, for example in countries like Costa Rica, Colombia, Morocco or Ethiopia, all countries that have set ambitious climate goals. The issue is currently experiencing welcome momentum. Still, we need to accelerate our efforts considerably. We ultimately need to sustainably change the global economy. We cannot and must not leave the brunt of climate change mitigation to the next generation.

Does this acceleration also apply to KfW?

Nagel: Definitely. We will further expand our commitment domestically and abroad.”

All in all everything suggests that this non-dogmatic, SPD-aligned veteran of 2008 will play nicely with Lagarde and his European colleagues.

It was telling that the FT wrapped up its report with a quote from Karsten Junius, chief economist at Bank J Safra Sarasin.

He said he hoped Nagel’s appointment would allow the Bundesbank “to criticise the monetary policy of the ECB less from the edge, but rather help shape it and explain it better in Germany”.

Likewise in Politico:

"He would signal a degree of Bundesbank continuity, coupled with market and international experience," said Berenberg economist Holger Schmieding. "He could turn into a bridge between the ECB and the German public, shaping ECB decisions while helping to explain them to the German public."

This is, indeed, what the Scholz administration and Europe need from the Bundesbank, a post-heroic accommodation with the dramatic change and a willingness to put Germany’s weight behind the irreversible project of monetary (and eventually financial) unification.

***

I love putting out Chartbook for free to a wide and diverse range of subscribers from all over the world. It is a pleasure to write and a great place to pull ideas together. It is also, however, a lot of work. If you feel moved to support the project, there are three subscription options:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Very interesting essay, as always. But it appears the link to Benjamin Braun's essay is broken.