Ones and Tooze this week is about JOLTS, the great resignation and about pets and pet food.

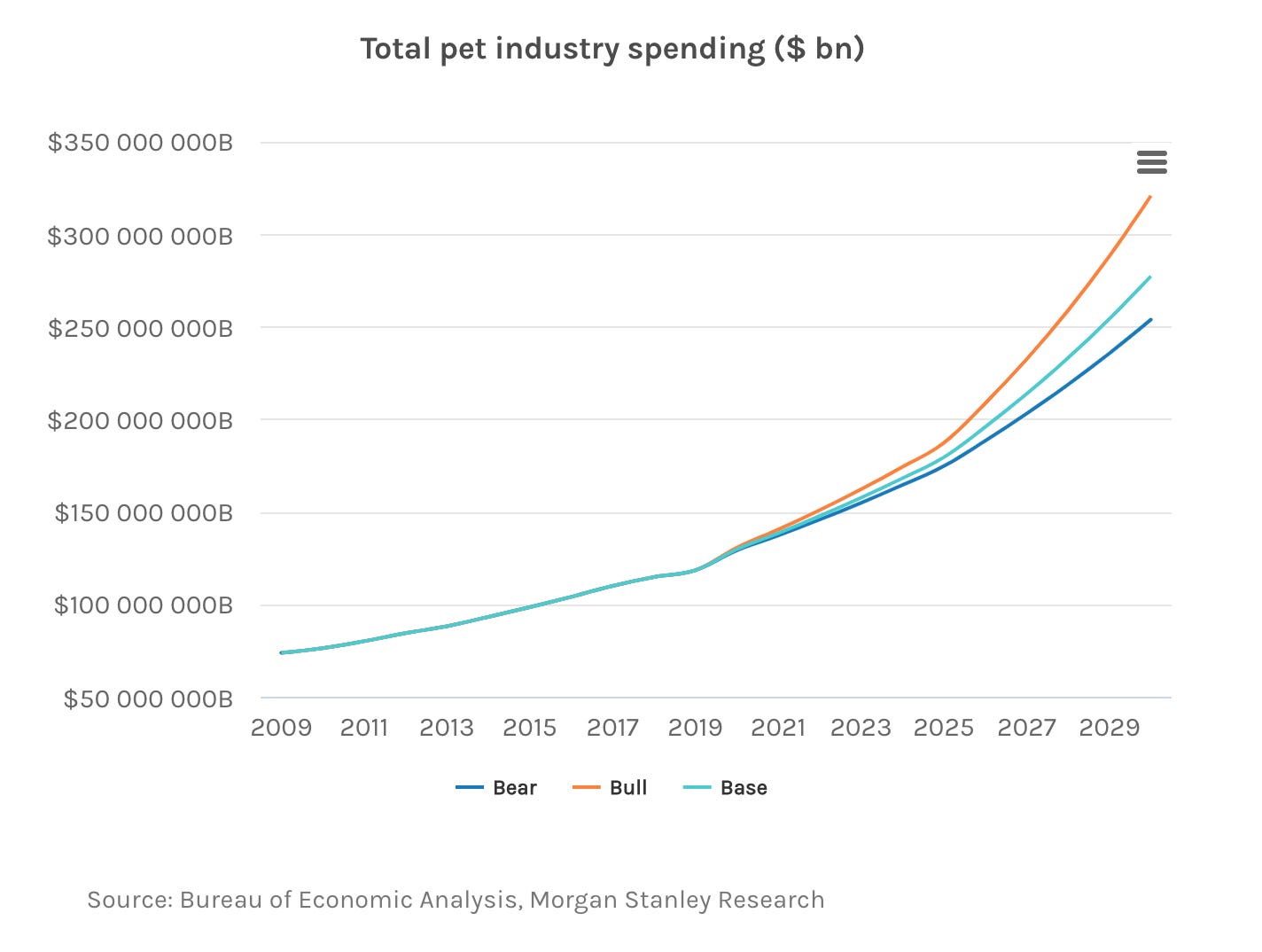

Its a huge industry. $100 billion per annum in spending in the US. And pet spending is highly income elastic. What drives it, is our deep attachment to companion animals.

As Cameron and I discuss living with a pet, particularly a human-centered dog can be a transformative experience - intimacy with a being that is not human.

In large part as a result of caring for Ruby, our Havanese, I’ve given up eating meat. As I would freely acknowledge, given the carnivorous appetites of dogs, this is not a straightforwardly logical response.

I’ve also acquired a new appreciation for the kind of animism that sees animals as the bearers of a peculiar spirit. That’s a rather highfalutin way of saying that the apartment in New York feels dead when Ruby the dog is not at home.

But I’ve also acquired an appreciation for the history of the human-canine relationship. The Havanese breed, it turns out, has a rather remarkable history, intertwined with Empire.

A constituency of amateur historians has dedicated themselves to unravelling a complicated narrative. Their work is a gift to anyone interested in canine history.

Havanese are one of the branches of the large family of bichon.

The family originated in the Mediterranean, where we find the Maltese and Bologenese breeds. In the 15th century they became entangled in a complex circulation of power and biology history within the Spanish empire, a circulation that runs by way of the Canary Islands.

The Canary Islands were first settled by humans and their livestock around 900 BC from north Africa. The romans gave them their name, Insular Canaria, not for birds - canaries - but for dogs (canaria).

After the fall of Rome, the Canary islands disappear from maps for many centuries, forming an isolated cultural, political and biological system.

In 1150 an Arab geographer wrote about them. In 1312 the Portuguese established a Catholic mission on Lanzarote (part of the Canary Islands). Traveling with Spanish and Italian sailors, small bichon dogs most likely arrived on the islands in the 1300s.

As a key launching pad for Atlantic exploration, the Canary Islands did not long escape the interest of the expanding Spanish empire. The Castilian ‘Reyes Catolicos’ (Catholic Kings) conquest of the Canary Islands began in early 1400’s and preceded through years of bloody struggle. Only in 1479 did the ruler of the Canaries recognize Spanish sovereignty, with Tenerife being the last island to surrender in 1496.

The great environmental historian Alfred W. Crosby offers a remarkable, “Ecohistory of the Canary Islands: A Precursor of European Colonialization in the New World and Australasia” in Environmental Review 1984.

In 1492, Columbus came to the islands to restock his western bound ship. It was by way of the Canary Islands the sugar cane most likely reached the Caribbean. And it was also from the Canary Islands that the ancestors of the Havanese dog arrived in Cuba.

In the mean time however, in a pattern that would repeat, the bichon dogs originally brought to the Canarys from Europe were reimported to Europe, and were given the name Tenerife dogs. They were a fashionable accessory in Renaissance court society, notably at the royal court of Francis I of France (1515-1547).

In this era they appeared in paintings by Titian.

Portrait of Federico II Gonzaga of Mantua (c. 1529) is a painting by Titian, who signed it Ticianus f. with his faithful Maltese.

Britain’s Queen Anne (1665-1714), a greater lover of dogs, acquiring two bichon after she saw them performing in a circus.

Anne, circa 1684, painted by Willem Wissing and Jan van der Vaardt

Goya (1746-1828) matched the Duchess of Alba or the White Duchess, with the fur of a bichon or a “white Havanese”.

Source: Wikipedia.

In Cuba, the Havanese bichon were the lap dogs of the local aristocracy.

Cuba was one of the richest islands in the Caribbean attracted many visitors. Havanese circulated as tourist trophies. They were not just lap dogs. They were gift dogs, presented as tokens to distinguished guests.

As one particularly rich history notes:

Cuban author and founder of the cuban Habanero Club, Zoila Portuendo Guerra brings forth perhaps the most logical theory in her book titled "Bichon Havanese". Her extensive research has attempted to sort through the lore, fact and fiction and presents a plausible progression that incorporates facets of the many other theories. She is adamant that there have been two Cuban breeds.

According to her, the first of these, was the now extinct "Blankito de la Havana" developed on the island in the 16th and 17th centuries during the days of Spanish colonization. This breed would have been a refinement of small bichons and lap dogs brought over directly from Spain or smuggled in illicitly by pirates and sea merchants. During these times, in Europe, tiny immaculate white dogs were the height of fashion as companions to the ladies of high society. The Cubans emulated this fashion in the development of the Blankito. He would have been a very small dog, weighing just 3-6 pounds, pure white, with a very silky, perhaps curly long coat. This original Cuban dog, the Blankito would have been the breed that returned to the continent in the early 18th century to be recognised with much fanfare. Much of the confusion surrounding the breed may come from the fact that in Cuba it was erroneously referred to as the "Maltese" while in Britain it was acclaimed as the "White Cuban". It was known throughout the rest of Europe as the "Havanese" because it came from Havana or later as the "Havana Silk Dog" because of the profuse soft coats. Mrs Guerra maintains that the Blankito would have remained a tiny white charmer till the early 19th century.

In the early 1800's many immigrants from Continental Europe settled on the island bringing with them their own little lap dogs, most notably small coloured poodles from France, Belgium and Germany. These new dogs were bred with the Blankito and a new breed subsequently evolved, a little bit larger and with a coat of many colours. The author portends that this second native of Cuba, created on the island during the 19th century is the Havanese breed as we know it today. Is this finally the actual account of our breed's history and development? Perhaps one of these accounts is true, but who can say for sure?

England’s first dog show, 'The Sporting Dog Show', was held in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1859. Non-sporting dogs were shown in Birmingham also in 1859. Havanese made their appearance on the show circuit in 1863 at The National Dog Show held in Chelsea.

Amongst the celebrity owners were Charles Dickens and Hemingway.

To speak in rather grand terms, the Havanese were a product of empire and its class structure. And the breed almost died with it.

The Cuban revolution of 1959 shook the social foundations of the island’s famous lap dog breed. And, at this point, the histories written by breed aficionados become contentious. The story of the Havanese becomes an anti-Communist morality tale.

According to the research of enthusiasts, in Cuba the breed collapsed. Many dogs were left behind as the defeated upper class abandoned the island. Only two families, the Perez and Fantasio, are known to have escaped Cuba with their dogs. “Their dogs are remembered as the first Havanese in America. Later it was learned Senor Ezekiel Barba had been able to escape to Costa Rica with his dogs.”

Some Havanese were also adopted and taken to the Communist bloc by Soviet and other East European advisors. They became known as the Iron Curtain Havanese.

In the US in the 1970s the cause of the breed was taken up by a dog-breeding couple Dorothy L. Goodale and her husband, Bert. Placing adverts in the Spanish language press in Miami they managed to collect enough dogs to form four distinct bloodlines. From that small group of dogs, all of the thousands of pedigree Havanese in the United States today are descended.

As one website notes:

“Not till 1991 was anyone sure that the Havanese still existed in Cuba. The Bichon Habanero Club was established to study the island's remaining indigenous dogs to ascertain their purebred status. After careful study and consideration, a closely supervised breeding program was put into place using a foundation stock of approximately 15 dogs.”

So this is the genealogy of Ruby our beloved housemate and companion. She is, not to put to finer point on it, a running dog of planter capitalism. I had previously known that phrase only as a classic of Maoist denunciation. Now I find myself with one as a member of my family, the descendant of a line that runs back perhaps 700 years.

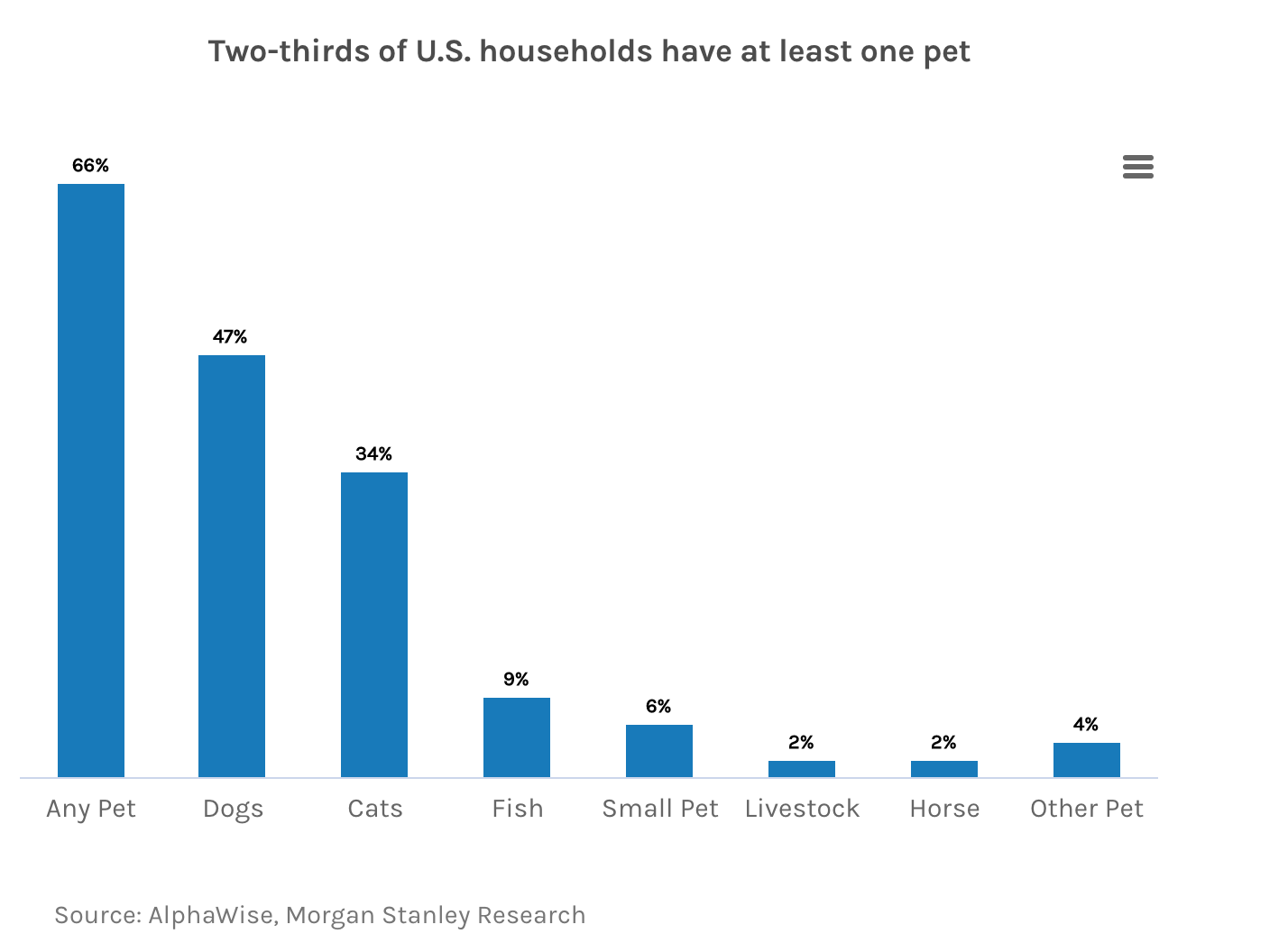

Oh and here are some charts on the pet industry from Morgan Stanley.

Fantastic stuff. So interesting. Very much the right dog for an economic historian, no? (About to share Thanksgiving with my son and his 80+ pound goofy blue-eyed Husky/Belgian Shepherd, Sophia. I may die in an avalanche of fur and tail-wagging.

This is a fantastic resource for anyone considering a Havanese! For a deeper dive into the pros and cons of owning this delightful breed, check out my article: Havanese Pros and Cons (https://www.nahf.org/article/havanese-pros-and-cons). It covers everything you need to know to decide if a Havanese is the right fit for your lifestyle. 😊