Chartbook 433 Globalization as a eurasian story.

World Economy Feb 2026

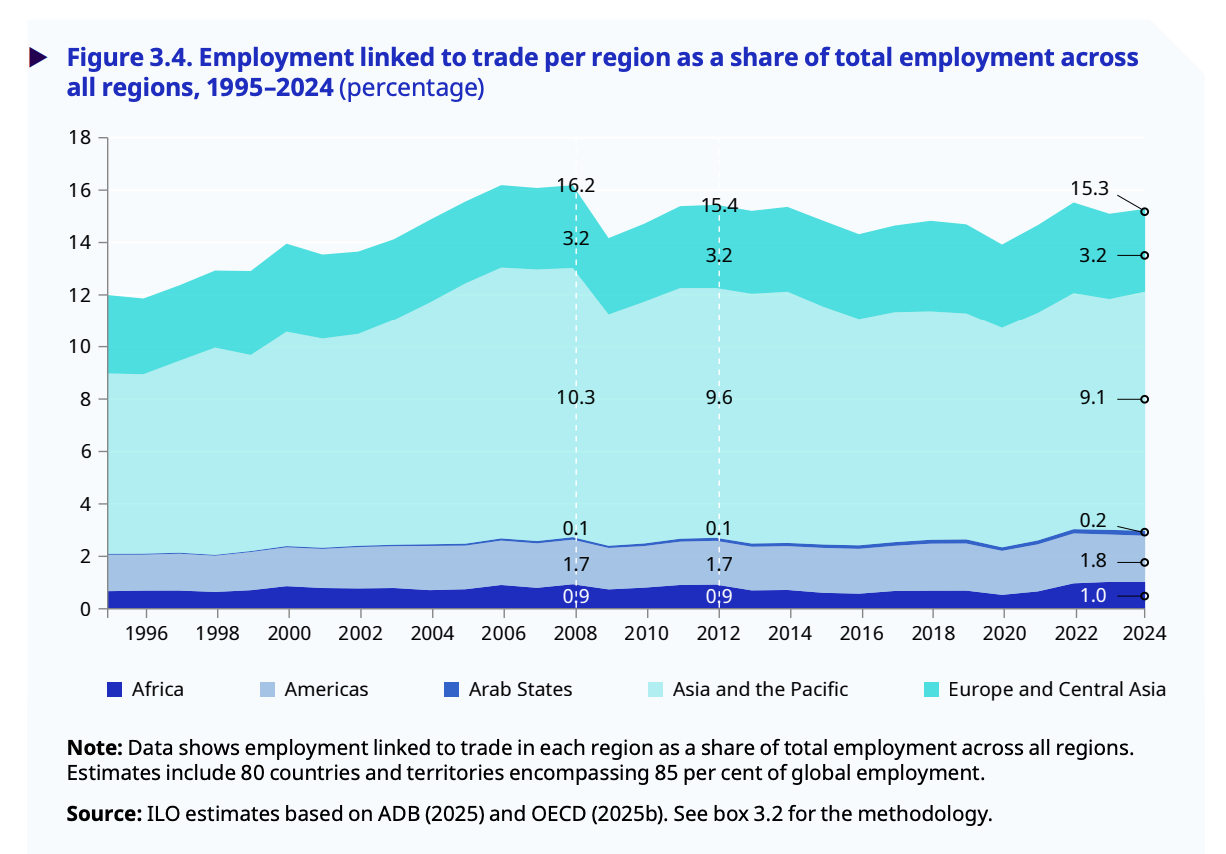

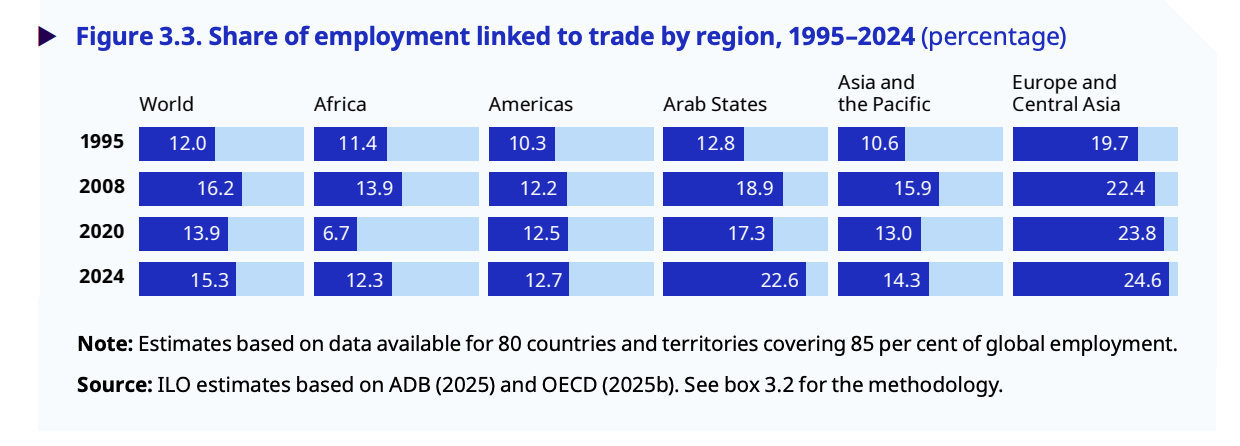

Eighty-one percent of employment linked to trade in good and services worldwide is in Asia and Pacific (60 percent) and in Europe and Central Asia (21 percent). As far as trade is concerned, globalization is a Eurasian story.

These staggering data come from the 2026 edition of the ILO’s Employment and Social Trends. They are an effect of overall size of the respective economies and their trade intensity. The Eurasian economy is huge and its trade share is higher than that of the Americas (which has a large economy) and Africa (with a large but very poor population). As the ILO explains:

In the 80 countries and territories with available data, 465 million jobs were linked to the global trade in goods and services in 2024, representing 15.3 per cent of total employment (see figure 3.3).2 Employment linked to trade includes all activities that directly or indirectly, through supply chains, meet foreign demand. Its regional distribution largely reflects the size of the labour force. Asia and the Pacific accounts for more than half of these jobs (278 million), followed by Europe and Central Asia with 96 million. The share of employment linked to trade within regions varies from 12.3 per cent in Africa to 24.6 per cent in Europe and Central Asia. Within Asia and the Pacific, the subregion of South-Eastern Asia stands out with 24.1 per cent of its employment linked to trade.

In 2024, the share of global employment linked to trade remained close to its 2012 level across the 80 countries and territories with available data (see figure 3.4), reflecting the prolonged stagnation in global trade. After falling by 2 percentage points in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, and then again by 0.8 percentage points during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, the share rebounded by 1.4 percentage points to reach 15.3 per cent in 2024. This suggests that trade was an important driver in the post-COVID employment recovery in all regions, apart from the Americas (see figures 3.3 and 3.4).

Punchline?

If we are to track the development of globalization, we should not start from North America!

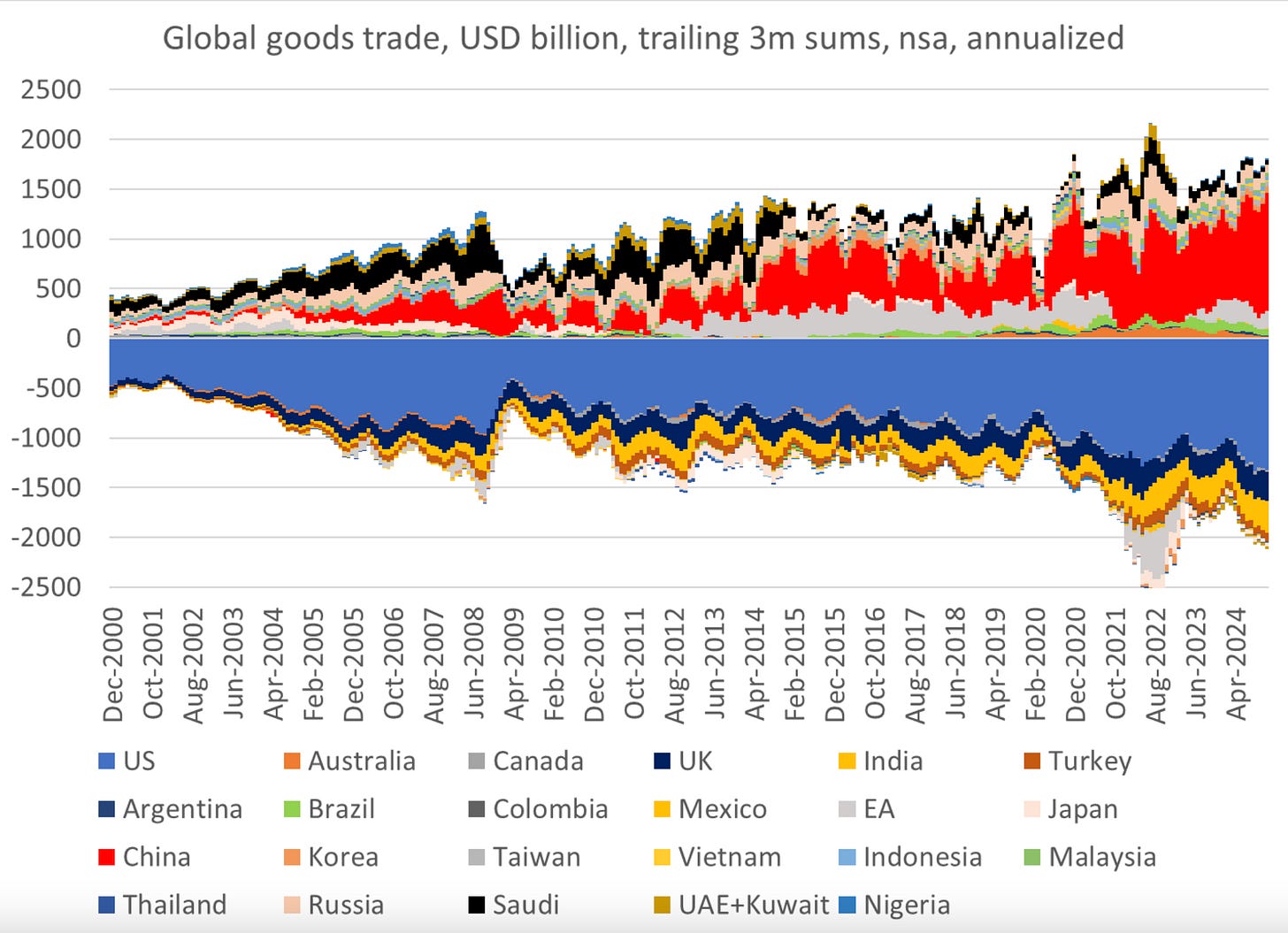

The US trade deficits may gape large. In the “global imbalances” vision of the world you can reduce the world economy to an American deficit and a Chinese surplus.

But as I argued in Chartbook 383 last year, which was supposed to start a regular series on the world economy (sorry), this dualistic perspective, because it focuses on “net” imbalances, can convey the wrong impression of the overall logic of economic activity worldwide.

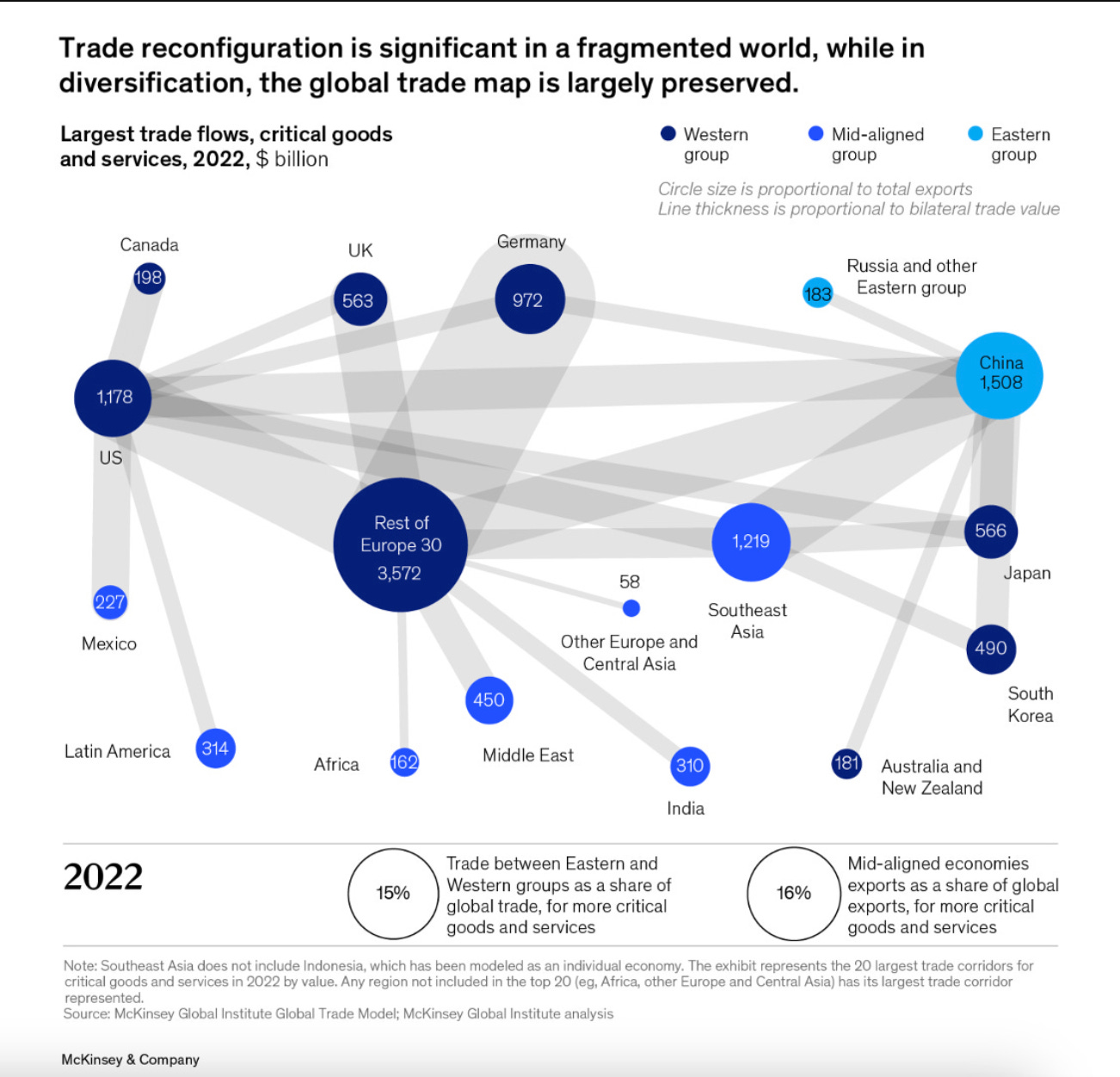

If you look at numbers like those of the ILO, or a graph that shows not just net deficits and surpluses but the “gross flows” i.e. the back and forth of imports and exports, you realize where the real center of the world economy lies, namely, in Europe, South East Asia and East Asia.

(Haven’t been able to find an updated version of these numbers from McKinsey).

Or, to put the punchline another way:

Globalization is “over” when Eurasia says it is, NOT when the USA has a protectionist temper tantrum.

BTW: If you wonder how the ILO compiles its figures, they add a helpful technical note:

The estimate of employment related to foreign demand is based on input–output modelling. Multi-country, multi-sector input–output tables permit the estimation of the value added required throughout the domestic and foreign supply chain to satisfy a certain final demand. The methodology involves multiplying the technical requirement matrix, also called Leontief inverse, with an appropriate demand vector (Timmer et al. 2015). For each country and sector, the method yields the share of value added required to satisfy total private and public consumption and investment in foreign countries. The analysis in this report uses the 2025 version of the inter-country input–output tables of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2025b). This database covers 50 economic activities in 80 countries and territories from 1995 to 2022. To derive estimates for 2023 and 2024, the analysis is supplemented with the multi-region input–output tables of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in its 74 economies version, which covers 35 economic activities for the years 2022 to 2024. The two databases have 61 economies in common, with 19 economies being exclusive to the OECD database and 13 mostly Asian economies exclusive to the ADB database. Employment per sector is derived from the ILO Harmonized Microdata repository, with missing values estimated using an equivalent methodology as is used for the ILO modelled estimates (ILO 2025a). The share of employment linked through trade to foreign demand within each economic activity included in the databases is assumed to be the same as the share of value added that has been established to be linked through trade. It is noteworthy that implied trade-related employment shares for 2022 can differ by a few percentage points at the sector level between both databases, despite the use of identical methodology and employment figures. Time-series estimates from 1995 to 2024 are generated for the 80 countries and territories included in the OECD database, where the estimates up to 2022 stem directly from the input–output methodology. For the 61 economies covered also by the ADB database, the annual changes between the years 2022 and 2024 in the share of employment linked to trade within six aggregate sectors are carried forward as of 2022. For the 19 economies unique to the OECD database, the trade-related employment shares within the detailed breakdown of economic activities from 2022 are also used for 2023 and 2024. For those economies, changes in the aggregate change in trade-related employment stem only from sectoral employment shifts – which is an important part of overall changes. The 80 countries and territories cover 85 per cent of global employment. Data availability by region: Africa (11 countries, 45 per cent of employment), Americas (9, 85 per cent), Arab States (3, 42 per cent), Asia and the Pacific (20, 96 per cent) and Europe and Central Asia (37, 91 per cent).

I love writing the newsletter. If you fancy buying me a coffee once a month, you know what to do. Chartbook will keep on coming to your mailbox in any case.

How does the "Rest of Europe 30" category in the McKinsey chart work exactly? Is that counting exports within the category as exports, ie say a Belgium to Netherlands export? Or is it only counting trade between Rest of Europe and other regions?

Paragraph breaks are a good thing ...